William George Baker (1864-1929) stands as a notable, albeit sometimes enigmatic, figure in New Zealand's art history. Primarily a self-taught artist, he became renowned for his evocative landscapes and, particularly, his depictions of Māori life and settlements during a period of significant cultural and societal transformation in New Zealand. His work offers a window into the colonial perception of the indigenous culture and the picturesque New Zealand landscape, capturing scenes that were rapidly changing. Baker's prolific output and the enduring popularity of his paintings underscore his significance in the narrative of New Zealand art, even as details of his life sometimes present a complex picture due to historical records occasionally conflating individuals of the same name.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born in 1864, the precise origins of William George Baker, the artist, are subject to some discussion, with sources variously suggesting Wellington, New Zealand, or Shotesham St Mary, Norfolk, England. However, his strong artistic association with New Zealand, particularly his focus on its unique landscapes and Māori subjects, firmly roots his artistic identity in the Southern Hemisphere. If born in England, he would have emigrated to New Zealand, a common path for many who contributed to the colonial arts scene. Regardless of his birthplace, it is widely accepted that Baker did not receive formal academic art training.

His development as an artist was therefore a journey of self-discovery and keen observation. In an era where formal art schools were less accessible, particularly in the colonies, many aspiring artists honed their skills through practice, by studying the works of other painters, and by direct engagement with their environment. Baker's dedication to his craft allowed him to achieve a remarkable level of proficiency, particularly in capturing the atmospheric qualities of the New Zealand landscape and the nuanced details of Māori architecture and daily life. This self-reliance speaks to a determined character, driven to express his vision of the world around him.

His emergence as a painter coincided with a growing Pākehā (New Zealanders of European descent) interest in the "exotic" and "romantic" aspects of Māori culture, as well as a burgeoning appreciation for the dramatic beauty of New Zealand's natural environment. Artists played a crucial role in shaping and disseminating images of the colony, both domestically and internationally. Baker tapped into this interest, producing works that resonated with the tastes of the time.

Artistic Focus: The New Zealand Landscape

New Zealand's diverse and often dramatic topography provided rich subject matter for artists of Baker's generation. He was particularly drawn to river scenes, tranquil lakes, and the distinctive bush that characterized much of the country. His landscapes often possess a serene, almost idyllic quality, emphasizing the natural beauty and, at times, the untouched wilderness of Aotearoa. Works like "Central Taupo Assessment," held in the Alexander Turnbull Library, exemplify his engagement with specific New Zealand locales.

Baker's approach to landscape painting was likely influenced by the prevailing European traditions, which colonial artists adapted to the unique light and forms of the New Zealand environment. The picturesque style, popular in the 19th century, which sought out views that were aesthetically pleasing and compositionally balanced, can often be discerned in his work. He demonstrated a good understanding of perspective and an ability to render the subtle interplay of light and shadow, bringing depth and realism to his canvases.

His landscape paintings were not merely topographical records; they often conveyed a mood or an emotional response to the scene. Whether depicting the misty reaches of a fiord, the calm expanse of a lake, or the dense foliage of the native bush, Baker sought to capture the essence of the New Zealand environment. These works contributed to a growing visual lexicon of New Zealand identity, helping to define how the land was perceived and valued.

Depictions of Māori Life: Idealization and Observation

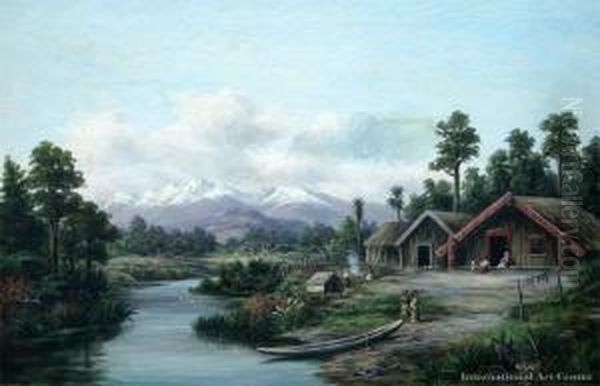

Perhaps William George Baker's most recognized contributions are his paintings featuring Māori subjects, particularly scenes of pā (fortified villages), whare (houses), and daily activities. These works were produced at a time when Māori society was undergoing profound changes due to colonization, land loss, and the imposition of European systems. Baker's paintings often present an idealized and romanticized vision of Māori life, emphasizing harmony, tranquility, and a picturesque existence.

His representative work, "Maori Pah, Waikato," which achieved a significant price at auction, is a prime example of this genre. Such paintings typically feature meticulously rendered details of traditional architecture, canoes, and figures engaged in communal activities, often set against a backdrop of stunning natural beauty. While these depictions were popular with European audiences, it's important to view them within the context of colonial attitudes. They sometimes perpetuated a notion of Māori culture as static or belonging to a bygone era, rather than reflecting the contemporary realities and resilience of Māori communities.

Despite this tendency towards idealization, Baker's works also demonstrate a degree of observation. The details in his paintings suggest a careful study of Māori material culture and settlement patterns. For artists like Baker, access to Māori communities and the opportunity to sketch and paint would have varied. His portrayals, while filtered through a European artistic lens, nonetheless contribute to the historical record of Māori life as perceived by Pākehā artists of the period. He joined other artists like Charles Frederick Goldie and Gottfried Lindauer, who were more famous for their detailed portraiture of Māori individuals, but Baker focused more on the communal and environmental aspects of Māori life.

The demand for such imagery reflected a complex mix of nostalgia, ethnographic curiosity, and a desire to capture what was perceived as a vanishing way of life. Baker's paintings catered to this market, providing Pākehā audiences with accessible and aesthetically pleasing representations of Māori culture.

Artistic Style and Techniques

William George Baker worked primarily in oils, a medium that allowed for rich color, depth, and detailed rendering. His style can generally be characterized as realistic, with elements of romanticism, particularly in his idealized depictions of Māori life and the picturesque qualities of his landscapes. He possessed a competent command of draftsmanship and composition, arranging elements within his paintings to create balanced and engaging scenes.

Later in his career, Baker also reportedly began to use watercolors. This medium, with its potential for translucency and quicker execution, might have offered him a different means of capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere in the New Zealand landscape. The shift or addition of watercolor to his repertoire would indicate an artist continuing to explore and adapt his technical skills throughout his career.

His palette often reflected the natural hues of the New Zealand environment – the deep greens of the bush, the blues and greys of the water and sky, and the earthy tones of the land and traditional structures. The application of paint was generally smooth, allowing for a clear depiction of form and detail, characteristic of much academic-influenced painting of the 19th and early 20th centuries, even for a self-taught artist absorbing these conventions. His work can be seen in the lineage of colonial landscape painters such as John Gully, J.C. Hoyte, and Alfred Sharpe, who all sought to capture the grandeur and unique features of New Zealand, though Baker's focus on Māori genre scenes gave him a particular niche.

Notable Works and Market Reception

Beyond "Maori Pah, Waikato" and "Central Taupo Assessment," William George Baker was a prolific artist, and many of his works have appeared at auction over the years, indicating a sustained collector interest. The consistent sale of his paintings, often depicting various river scenes, lake views, and Māori settlements around areas like the Waikato River, Rotorua, and Lake Taupō, speaks to their enduring appeal. Each work, while often sharing thematic similarities, would offer a unique composition or focus, contributing to a broad portfolio that captured many facets of the New Zealand scene as he saw it.

The art market's continued engagement with Baker's work reflects its historical and aesthetic value. His paintings are sought after not only for their artistic merit but also as historical documents that offer insights into colonial New Zealand. The prices achieved at auction, such as the $11,963 for "Maori Pah, Waikato," while perhaps modest compared to some internationally renowned artists, are significant within the New Zealand art market and indicate a strong appreciation for his contribution.

It is important to distinguish the artist William George Baker from other individuals with similar names who may appear in historical records. For instance, references to works like "The Devil's Harvest" or "The Suspicions of Mr Whicher" are highly unlikely to be connected to this New Zealand painter and more probably refer to literary or film titles associated with other creators. Similarly, accounts of a William George Baker with a "strict judicial style" or involvement in political controversies related to a judge's salary clearly describe a different person, likely a magistrate or legal figure, not the artist. Such conflations are common in historical research but must be carefully disentangled to appreciate the specific contributions of the artist.

Context and Contemporaries

William George Baker operated within a vibrant and evolving New Zealand art scene. While he was self-taught, he would have been aware of the work of his contemporaries. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a number of artists, both trained and self-taught, working to define a visual language for New Zealand.

As mentioned, Charles Goldie (1870-1947) and Gottfried Lindauer (1839-1926) were pre-eminent in their portraiture of Māori, often with a strong ethnographic intent, though sometimes tinged with the romanticism of the "noble savage" or the "last of their race." Baker's work, while sharing the Māori subject matter, differed in its focus on genre scenes and landscapes incorporating Māori life, rather than formal portraiture.

In landscape painting, artists like John Gully (1819-1888), J.C. Hoyte (1835-1913), and Alfred Sharpe (c.1836-1908) were significant figures who established traditions of depicting New Zealand's natural grandeur, often influenced by Romantic and Picturesque conventions. Petrus Van der Velden (1837-1913), a Dutch immigrant, brought a more expressive, moody European style to New Zealand landscape and genre painting, particularly evident in his depictions of the Otira Gorge.

The period also saw the emergence of artists who would push New Zealand art in more modern directions, such as Frances Hodgkins (1869-1947), who, although a contemporary, moved towards European modernism and spent much of her career abroad. Other notable New Zealand artists of the broader period whose work contributed to the artistic milieu include Louis John Steele (1842-1918), known for historical and Māori subjects, often in collaboration with Goldie, and landscape painters like Charles Blomfield (1848-1926) and E.W. Payton (1859-1944). Even the early surveyor-artists like Charles Heaphy (1820-1881) laid groundwork in documenting the landscape. Baker's work sits comfortably within this tradition of representational art that sought to capture and interpret the New Zealand experience for a colonial audience.

Later Life and Military Service Considerations

William George Baker continued to paint for much of his life, contributing a significant body of work over a career that spanned several decades. He passed away in 1929. Some records indicate that a William George Baker, born in 1864, served in the Machine Gun Corps during World War I with the service number M 25814 and died in West Norwood, London, from natural causes. If this is indeed the artist, it adds another dimension to his life story, placing him among the many New Zealanders who contributed to the war effort. He would have been in his early fifties at the outbreak of the war.

The death occurring in London is plausible, as many colonial artists maintained connections with Britain, and some returned there in their later years. However, without definitive biographical linkage, the military service detail, while noted in some sources, should be considered with the understanding that records for individuals with common names can sometimes be conflated. The core of his legacy, however, remains firmly tied to his artistic output in New Zealand.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

William George Baker's legacy is primarily that of a diligent and prolific painter who captured a specific vision of colonial New Zealand. His works are valuable historical documents, offering insights into how the landscape and Māori culture were perceived and represented by Pākehā artists during his lifetime. His paintings of Māori pā and daily life, while often idealized, remain an important part of the visual record of Māori culture from a colonial perspective.

The enduring popularity of his works in the art market testifies to their aesthetic appeal and historical significance. Collectors and institutions value his paintings for their charm, their detailed rendering, and their evocation of a particular period in New Zealand's history. He is recognized as one of the notable self-taught artists who made a significant contribution to the country's artistic heritage.

While he may not have been an innovator in the modernist sense, like his contemporary Frances Hodgkins, Baker excelled within the representational traditions of his time. He provided his audience with images that were both familiar and evocative, capturing the beauty of the New Zealand landscape and a romanticized vision of Māori life that resonated with colonial sensibilities. His work continues to be studied and appreciated for its role in the broader narrative of New Zealand art, reflecting the cultural currents and artistic practices of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His contribution, alongside artists like Walter Wright (1866-1933) and Kennett Watkins (1847-1933) who also painted Māori scenes and landscapes, helps to form a more complete picture of the artistic endeavors of the era.

In conclusion, William George Baker was a dedicated artist whose paintings of New Zealand landscapes and Māori subjects have secured him a lasting place in the country's art history. His work, characterized by its detailed realism and often romantic sensibility, offers a valuable glimpse into the colonial past, reflecting both the beauty of Aotearoa and the complex cultural dynamics of his time.