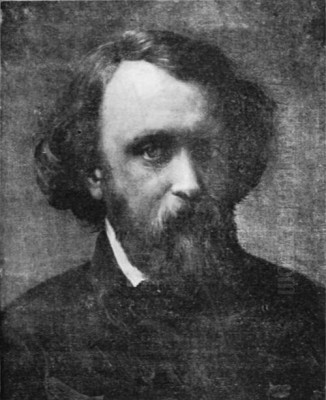

Auguste François Ravier stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in 19th-century French art. A landscape painter of remarkable sensitivity and innovative technique, he navigated the currents between Romanticism and the burgeoning Impressionist movement. Born in Lyon on May 4, 1814, and passing away in Morestel on June 26, 1895, Ravier dedicated his life to capturing the ephemeral effects of light and atmosphere, particularly in the landscapes of the Dauphiné region and Italy. His work, characterized by bold color and expressive brushwork, marks him as a crucial precursor to Impressionism, influencing artists and leaving a distinct legacy centered on the emotional power of nature's light.

Early Life and Artistic Calling

Ravier's journey into the world of art was not a straightforward path dictated by family tradition. Born into a family with legal connections in Lyon – his father was involved in the legal profession – the expectation was for Auguste to follow a similar career. He dutifully pursued legal studies in Paris, aligning with his father's wish for him to become a notary. However, the allure of art proved irresistible. While ostensibly studying law, Ravier was simultaneously immersing himself in drawing and painting, nurturing a passion that would soon eclipse his legal pursuits entirely.

This burgeoning dedication led him to seek formal training. He entered the studios of prominent artists who could guide his developing talent. Key figures in his early artistic education included Jules Coignet and Théodore Caruel d'Aligny. These instructors, established in the landscape tradition, provided Ravier with foundational skills. Yet, even in these early stages, Ravier's independent spirit and unique vision began to surface, hinting at the distinctive style he would later develop. His decision to ultimately abandon law for a full-time commitment to painting marked a definitive turn, setting him on a course dedicated solely to artistic exploration.

The Formative Italian Journeys

A pivotal period in Ravier's artistic development occurred between 1840 and 1847, during which he undertook several influential trips to Italy. Drawn by the legendary light and the rich artistic heritage, Ravier immersed himself in the Italian landscape and its cultural milieu. Rome, in particular, served as a significant base and source of inspiration. These journeys were not mere sightseeing expeditions; they were intensive periods of study, observation, and artistic production. The unique quality of Mediterranean light profoundly affected his perception and technique, encouraging a bolder use of color and a heightened sensitivity to atmospheric effects.

During his time in Italy, Ravier encountered and forged connections with other artists, both French and international. Crucially, he associated with Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a leading figure in French landscape painting whose lyrical approach to nature resonated with Ravier. While influenced by Corot's tonal harmonies and compositional elegance, Ravier's own work was already pushing towards a more intense and color-focused expression. He also formed friendships with other notable artists like Charles-François Daubigny, another key figure associated with the Barbizon School. These interactions and the direct experience of Italian light and landscape were instrumental in shaping his artistic identity.

Artistic Style: Light, Color, and Emotion

Ravier's artistic style is defined by its intense focus on capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere. While rooted in the Romantic tradition's emphasis on nature's emotional power, his technical approach anticipated many concerns of the Impressionists. He was particularly drawn to the dramatic moments of dawn and sunset, times when light transforms the landscape into a spectacle of color and shadow. His goal was not topographical accuracy in the traditional sense, but rather the evocation of a specific mood and the sensory experience of being within the landscape.

To achieve this, Ravier employed a distinctive technique. His brushwork could be rapid, almost "feverish," as some described it, using thick impasto in places to convey the texture of the land or the brilliance of light hitting a surface. He often worked with bold, saturated colors, layering them or placing them side-by-side to create vibrant effects. This focus on color and light as the primary means of expression, often prioritizing them over precise linear definition, clearly marks him as a forerunner to Impressionism. He sought to translate the sensation of light, a core tenet that would later define the Impressionist movement.

His mastery extended particularly to watercolor. In this medium, he achieved remarkable luminosity and fluidity, using the transparency of the washes to build up layers of light and atmosphere. Works like Étude de ciel à l'aube sur papier à l'eau fine grain blanchie (Study of Dawn Sky) exemplify his skill in capturing the delicate and shifting hues of the sky. Whether in oil or watercolor, Ravier's approach was experimental and deeply personal, driven by his direct observation and emotional response to the natural world.

Key Influences and Artistic Dialogue

While Ravier forged a unique path, his work developed within a rich context of artistic influences and dialogues. The impact of Camille Corot is undeniable, particularly in the structure and poetic sentiment found in some of Ravier's landscapes. However, Ravier consistently pushed beyond Corot's more restrained palette, embracing a higher chromatic intensity. His time in Italy exposed him not only to Corot but also to the legacy of classical landscape painting and the vibrant southern light that had inspired artists for centuries.

Ravier also maintained connections with the Barbizon School, a group of painters dedicated to realistic depictions of the French countryside, often working directly from nature (en plein air). Figures like Charles-François Daubigny, Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña shared Ravier's commitment to landscape as a primary subject. While Ravier shared their love for nature, his emphasis on subjective light effects and expressive color set him somewhat apart from the Barbizon painters' often more earthy tones and detailed realism.

Furthermore, one can perceive parallels, if not direct documented influence, with the work of the British master J.M.W. Turner. Both artists were profoundly interested in the atmospheric power of light, particularly in dramatic sunsets and turbulent skies, and both used color with extraordinary freedom and expressiveness. Ravier's work, like Turner's, often dissolves form into light and color, prioritizing atmospheric sensation over literal representation. This shared sensibility highlights Ravier's place within a broader European exploration of light and landscape during the 19th century.

The Morestel Years and the Dauphiné Landscape

Around 1867 or 1868, Ravier made a decisive move, settling permanently in the small town of Morestel, located in the Dauphiné region of southeastern France, near his native Lyon. This area, with its rolling hills, ponds, and distinctive light, became the primary subject of his mature work. He found endless inspiration in the local scenery, particularly the dramatic sunsets over the plains and the reflections in the numerous small lakes and ponds. His paintings from this period are intimate yet powerful portrayals of this specific environment, imbued with his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere.

In Morestel, Ravier acquired a house that would become central to his life and legacy – now known as the Maison Ravier. This building served not only as his home and studio but also became a gathering place for artists and a space where art could be appreciated. He became a significant figure in the local art scene, his presence attracting other painters to the region. His deep connection to Morestel and the surrounding landscape is evident in the sheer volume and emotional intensity of the works he produced there. The Maison Ravier stands today as a museum dedicated to his work and that of other artists associated with the region.

Notable Works and Signature Themes

While Ravier was prolific, certain works and recurring themes stand out. His depictions of sunsets are perhaps his most iconic subjects. He returned again and again to the spectacle of the setting sun, exploring the infinite variations of color and light as day transitioned into evening. These paintings are often characterized by fiery reds, oranges, and yellows contrasted with deep blues and purples, applied with vigorous brushstrokes that convey the energy and fleeting nature of the moment.

Specific titles mentioned in records include Landscape with Pond near Crémieu and works generally titled Landscape near Morestel or depicting specific times of day, like his dawn sky studies. These titles often emphasize the location or the atmospheric condition, reflecting his primary concerns. His landscapes frequently feature water – ponds or rivers – which allowed him to explore the complex play of reflections and light on the water's surface. The compositions are often simple, focusing attention on the sky and its interaction with the land. The scale of his works varies, but many are relatively intimate, inviting close contemplation of their rich surfaces and luminous effects.

A Circle of Contemporaries and Collaborators

Ravier's artistic life was enriched by his interactions with a wide circle of fellow artists. His early mentors, Jules Coignet and Théodore Caruel d'Aligny, provided his initial grounding. His travels in Italy brought him into the orbit of giants like Corot and Daubigny, relationships that were influential throughout his career. His friendships extended to other significant figures in the art world, demonstrating his integration within the artistic currents of his time.

Sources mention friendships with artists such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Hippolyte Flandrin (a fellow Lyonnais), and Eugène Delacroix, representing connections across different stylistic camps, from Neoclassicism to Romanticism. He was also friends with landscape painters like François Lamy and Henri Harpignies. In the Dauphiné region, he collaborated with Gustave Eugène Castan in the 1850s, blending influences from the Barbizon and Lyon schools. His connection to the Impressionist circle is suggested through links with Camille Pissarro.

His role as a mentor is primarily associated with François Guiguet, who became his sole dedicated pupil. Although Guiguet ultimately specialized in portraiture rather than landscape, Ravier's guidance was formative. Ravier also exhibited alongside contemporaries, and the Maison Ravier later showcased works by artists like Joseph Communal, further cementing his place within the regional artistic community. This network underscores Ravier's position not as an isolated figure, but as an active participant in the artistic life of 19th-century France. Other artists from Lyon he likely knew included Adolphe Appian and possibly Félix Ziem, known for his luminous Venetian scenes and seascapes.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Photography

Throughout his career, Ravier sought recognition through established channels, regularly submitting his work to the prestigious Paris Salon. While details of specific acceptances or rejections might vary, his participation indicates his engagement with the official art world of his time. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain visibility and patronage, and Ravier's presence there helped to disseminate his unique vision of landscape painting.

Interestingly, Ravier was also among the painters of his generation who explored the possibilities of the new medium of photography. While not primarily known as a photographer, his interest in this technology aligns with his artistic concerns. Photography offered a new way of capturing light, shadow, and fleeting moments, potentially informing his observational skills or serving as an aid to composition, although his paintings always retained a highly subjective and painterly quality far removed from photographic literalism. His exploration of photography underscores his forward-looking mindset and interest in different modes of visual representation.

His most lasting public recognition is perhaps embodied by the Maison Ravier in Morestel. Established as a museum after his time, it preserves his studio and showcases a significant collection of his paintings and watercolors, alongside works by his pupil Guiguet and other regional artists. This dedicated space ensures that his contribution to French art remains accessible and celebrated, particularly his profound connection to the Morestel landscape. Regular exhibitions held there continue to explore his work and its context.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Auguste François Ravier occupies a crucial position in the evolution of French landscape painting. He serves as a vital link between the Romantic sensibility of the early 19th century and the revolutionary optical concerns of Impressionism. While not an Impressionist himself in the formal sense – he did not exhibit with the group – his intense focus on capturing the effects of natural light, his bold and often broken application of color, and his emphasis on subjective perception over objective detail clearly anticipated their innovations. Artists like Pissarro acknowledged his importance.

His dedication to the landscape of the Dauphiné region helped to establish it as a significant location for artistic exploration, attracting other painters and contributing to the development of the Lyon School of painting. His direct influence can be seen in the work of his pupil, François Guiguet, even though Guiguet pursued a different genre. More broadly, Ravier's unwavering commitment to his personal vision and his innovative techniques demonstrated an independent spirit that resonated with the move away from academic constraints towards more modern approaches to art.

Today, Ravier is celebrated for the sheer beauty and emotional intensity of his landscapes. His ability to translate the power of light and atmosphere onto canvas and paper remains compelling. The Maison Ravier in Morestel stands as a testament to his life and work, ensuring his legacy endures. He is recognized as a master of watercolor and a painter whose unique vision significantly contributed to the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art, a pioneer whose luminous works continue to captivate viewers.

Conclusion: A Master of Light

Auguste François Ravier's artistic journey was one of dedicated exploration into the heart of landscape and light. From his early defiance of familial expectations to his formative Italian travels and his deep immersion in the Morestel countryside, he pursued a singular vision. Bridging the gap between the emotional depth of Romanticism and the perceptual innovations of Impressionism, Ravier developed a style characterized by vibrant color, expressive technique, and an unparalleled sensitivity to atmospheric effects. His paintings, particularly his sunsets and watercolors, are powerful testaments to nature's transient beauty. Remembered through his captivating works and the dedicated museum in his Morestel home, Ravier stands as a significant French master, a true pioneer of light.