Denis Auguste Marie Raffet stands as a pivotal figure in 19th-century French art, celebrated primarily for his mastery of lithography and his evocative depictions of military life, particularly during the Napoleonic era. Born in Paris on March 2, 1804, and passing away in Genoa on February 16, 1860, Raffet's life spanned a period of immense political and social change in France, events that deeply informed his artistic output. His work not only captured the visual details of historical moments but also contributed significantly to the shaping of collective memory, especially concerning the figure of Napoleon Bonaparte and his armies.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Raffet's origins were modest. Born in Paris, he did not initially pursue an artistic path in the conventional academic sense. His early training was practical; he began as a carpenter's apprentice. However, a passion for drawing led him to attend evening art classes, nurturing a talent that would eventually define his career. This initial distance from the established art institutions perhaps fostered a unique perspective, less bound by rigid academic conventions.

A crucial turning point came when Raffet sought formal instruction. He entered the studio of Nicolas Toussaint Charlet, himself a renowned painter and lithographer specializing in military subjects. Under Charlet's guidance, likely between 1824 and 1829, Raffet honed his skills in drawing and, significantly, mastered the techniques of lithography. Charlet's influence is palpable in Raffet's early work, particularly in the choice of subject matter and the sympathetic portrayal of the common soldier.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Raffet also became a student of Baron Antoine-Jean Gros at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. Gros was a giant of French painting, a pupil of Jacques-Louis David, famous for his large-scale, dramatic canvases depicting Napoleonic battles and events. Studying under Gros exposed Raffet to the grand tradition of history painting and likely refined his sense of composition and dramatic narrative, even though Raffet would ultimately find his primary voice in the more intimate medium of printmaking.

The Embrace of Lithography

In 1830, Raffet competed for the prestigious Prix de Rome, the ultimate prize for aspiring history painters, which offered years of study in Italy. His failure to secure this award proved serendipitous. Disappointed but undeterred, Raffet turned his full attention to lithography, a medium that had gained considerable popularity in France since its invention in the late 18th century. Lithography offered artists greater freedom and spontaneity compared to traditional engraving, allowing for rich tonal variations and a directness akin to drawing.

This medium perfectly suited Raffet's talents and thematic interests. It allowed for the relatively inexpensive reproduction and wide dissemination of images, making his work accessible to a broader public eager for visual representations of recent history and contemporary events. Raffet quickly demonstrated exceptional skill, exploiting the full potential of the lithographic crayon to create images brimming with detail, atmosphere, and energy. He joined a generation of brilliant French lithographers, including masters like Honoré Daumier and Paul Gavarni, though Raffet carved a distinct niche with his focus on military and historical subjects.

Chronicling the Napoleonic Legend

Raffet's name became inextricably linked with the depiction of the Napoleonic Wars. Working in the decades following Napoleon's fall, during periods (the July Monarchy, the Second Republic, and the Second Empire) where nostalgia for the Emperor's era fluctuated but remained potent, Raffet's lithographs played a significant role in cultivating and sustaining the "Napoleonic Legend." His works often moved beyond simple illustration to capture the perceived glory, sacrifice, and camaraderie of the Grande Armée.

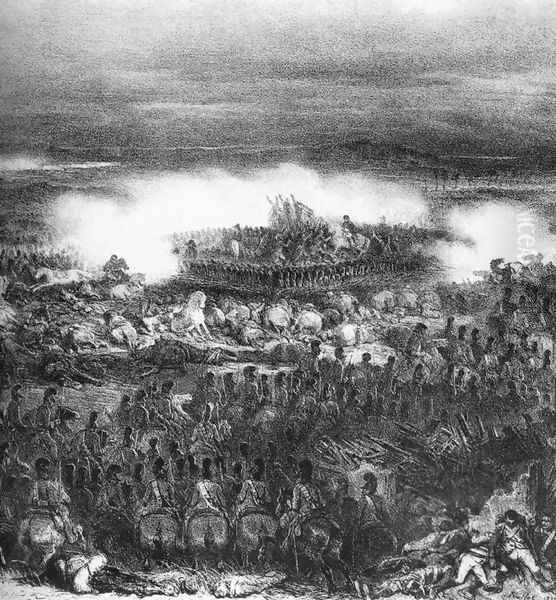

Among his most celebrated works in this vein are powerful scenes like Lützen and Waterloo, which convey the chaos and scale of major battles. However, Raffet was equally adept at capturing quieter, more personal moments. La revue (The Review) and the particularly famous La revue nocturne (The Nocturnal Review), inspired by a poem by Joseph Christian von Zedlitz, depict ghostly Napoleonic troops parading, evoking a powerful sense of memory and myth. Les adieux de la garnison (Farewell of the Garrison) captures the poignant human element of military life.

Unlike the heroic, often idealized canvases of his teacher Gros or the Neoclassical propaganda of Jacques-Louis David, Raffet frequently focused on the collective experience of the soldiers. His figures, while meticulously rendered in their uniforms and equipment, often appear as part of a larger, dynamic mass, subject to the vast forces of history and war. Yet, he imbued these scenes with a palpable energy and patriotic fervor that resonated deeply with contemporary audiences. His work provided a visual touchstone for a nation grappling with its recent, tumultuous past. He can be seen alongside Théodore Géricault, whose dramatic military paintings like The Charging Chasseur also captured the Romantic spirit of the era.

Beyond the Empire: Other Campaigns

While the Napoleonic era remained a central theme, Raffet's artistic gaze extended to contemporary military conflicts involving France. He produced significant works documenting the French conquest of Algeria, a major colonial undertaking of the July Monarchy. His series on the Prise de Constantine (Capture of Constantine) in 1837 provided dramatic, albeit often romanticized, views of the campaign, contributing to the visual culture surrounding French colonialism. These works sometimes intersected with the burgeoning Orientalist interests seen in painters like Eugène Delacroix, though Raffet's focus remained primarily military.

Raffet also documented the French intervention in Italy. He was present during the Siege of Rome in 1849, where French troops helped restore Pope Pius IX, and he produced a series of lithographs depicting the event. Later, he created images of the Italian Campaign of 1859, including the Bataille de Solférino (Battle of Solferino). These works demonstrate his continued engagement with military reportage, capturing the immediacy and brutality of modern warfare with his characteristic detail and dynamism. His work in Algeria paralleled that of other artists engaged with the conflict, such as Horace Vernet, with whom Raffet sometimes collaborated or shared thematic interests.

Travels, Patronage, and Observation

Raffet's horizons were further broadened by travel. A significant episode was his journey in 1837 accompanying the wealthy Russian nobleman and industrialist, Prince Anatole Demidoff I, on a scientific and artistic expedition to Southern Russia, the Crimea, Hungary, and Wallachia. Demidoff was an important patron, and this trip provided Raffet with a wealth of new subjects and experiences beyond the familiar French military context.

Raffet served as the official illustrator for the expedition, producing numerous drawings and watercolours documenting the landscapes, people, costumes, and historical sites they encountered. One hundred of his plates were later published in Demidoff's lavish multi-volume account, Voyage dans la Russie méridionale et la Crimée, par la Hongrie, la Valachie et la Moldavie (Paris, 1840-1848). This journey showcased Raffet's versatility and keen powers of observation, extending his range to ethnographic and landscape subjects, touching upon themes explored by dedicated Orientalist painters like Prosper Marilhat.

Artistic Style and Technical Mastery

Raffet's artistic style is characterized by a blend of Romantic sensibility and meticulous realism. His compositions are often dynamic and complex, filled with figures and action, yet rendered with remarkable clarity. He possessed an exceptional ability to capture movement – the charge of cavalry, the march of infantry, the smoke and chaos of battle. His attention to detail was legendary, particularly concerning military uniforms, weaponry, and accoutrements, making his works valuable historical documents.

Technically, Raffet was a virtuoso of lithography. He masterfully employed the lithographic crayon to achieve a wide range of tones, from deep, velvety blacks to delicate greys and brilliant highlights, often enhanced by scraping techniques on the stone. This tonal richness gave his prints remarkable depth and atmosphere. He understood how to use light and shadow dramatically to focus attention and heighten emotion. While primarily known for his black and white lithographs, Raffet was also a skilled watercolourist, often using this medium for preparatory studies or finished works that displayed a more fluid and colourful approach.

His depictions of landscape and nature, whether as backdrops to military scenes or as subjects in their own right (particularly from his travels), show a sensitivity to atmosphere and the changing effects of light and weather. This ability to integrate figures convincingly within their environment adds another layer of realism and emotional resonance to his work.

Collaborations and Artistic Milieu

Throughout his career, Raffet moved within a vibrant artistic circle, particularly among those specializing in military and historical themes. His formative relationship with Nicolas Toussaint Charlet was foundational. He also maintained connections with his other teacher, Antoine-Jean Gros, a link to the grand tradition of Napoleonic painting.

He frequently collaborated or worked in parallel with contemporaries like Horace Vernet and Hippolyte Bellangé. Vernet, a prolific painter and director of the French Academy in Rome, was renowned for his vast battle canvases and scenes of Algerian life. Bellangé, like Charlet and Raffet, focused heavily on lithographs and paintings of military life, often with a sentimental or anecdotal touch. Together, these artists shaped the popular imagery of the French soldier and military history in the mid-19th century.

Raffet's work should also be understood in the context of broader Romanticism, alongside figures like Géricault and Delacroix, who explored themes of heroism, struggle, emotion, and the exotic. While Raffet's style often incorporated a high degree of realism, the dramatic energy and emotional intensity of his work align firmly with Romantic ideals. Later artists specializing in highly detailed military scenes, such as Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, undoubtedly looked back at the legacy established by Raffet and his generation.

Notable Works and Anecdotes

Beyond the famous Napoleonic scenes, certain works and events illuminate Raffet's career. His critical lithograph Le Barbarisme et le Choléra entrant en Europe (Barbarism and Cholera Entering Europe), created around 1831-32, depicted Russian soldiers as agents of disease and oppression following their brutal suppression of the Polish Uprising. This work demonstrated his willingness to engage with contemporary political commentary, aligning him briefly with the sharp social critique often found in the work of Honoré Daumier.

An interesting anecdote reflecting the era's publishing practices involves the unauthorized use of his work. Some of Raffet's illustrations were reportedly altered or reused without proper credit in publications in Belgium, notably by one Adolphe Wahlen, highlighting the sometimes-tenuous nature of artistic copyright and recognition in the period.

Raffet's dedication to his craft was immense, resulting in a prolific output. After his death, his son Auguste Raffet recognized the historical and artistic value of his father's legacy. He generously donated a vast collection, comprising over 3,800 drawings, watercolours, and prints, to the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (French National Library) in Paris. This donation remains a cornerstone for the study of Raffet's work and the visual culture of his time. His works are also held in major museum collections, including the Louvre.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Auguste Raffet's primary legacy lies in his powerful contribution to the visual record of 19th-century French military history and his role in shaping the enduring image of the Napoleonic soldier. His lithographs were not merely illustrations; they were dynamic, emotionally charged interpretations that captured both the grandeur and the human cost of war. He provided a visual language for national memory, particularly concerning the Napoleonic epic, that resonated for generations.

As a lithographer, he demonstrated the artistic potential of the medium, pushing its technical boundaries and creating works of remarkable detail, complexity, and atmospheric power. His meticulous attention to historical accuracy, especially in military details, made his work invaluable for historians and enthusiasts, a standard that influenced later military illustrators.

While perhaps less famous today than some of the leading painters of his era, Raffet's influence was significant. He successfully bridged the gap between historical documentation and artistic expression, using a popular medium to reach a wide audience. His ability to convey intense action, historical drama, and human emotion through printmaking secured his place as a master of lithography and a key visual chronicler of a transformative period in French history.

Conclusion

Denis Auguste Marie Raffet was more than just an illustrator of battles. He was a visual historian, a master craftsman of lithography, and a sensitive observer of the human condition within the crucible of conflict and historical change. From the battlefields of the Napoleonic Wars to the landscapes of Southern Russia, his work provides a rich and detailed panorama of his time. Through his prolific output, technical brilliance, and ability to capture the spirit of an era, Raffet made an indelible mark on French art and the visual memory of the 19th century. His legacy endures in the vast collection of his works and in the continuing fascination with the historical moments he so vividly brought to life.