Introduction: An Artist Born to Paint

Émile Jean-Horace Vernet, known universally as Horace Vernet, stands as a towering figure in 19th-century French art. Born in Paris on June 30, 1789, and passing away in the same city on January 17, 1863, Vernet's life spanned a period of immense political upheaval and artistic transformation in France. He was not merely an observer of his times; he was an active chronicler, capturing the dynamism, conflicts, and changing tastes of the era through his prolific output. Renowned primarily for his large-scale battle paintings, insightful portraits, and captivating Orientalist scenes, Vernet achieved immense popularity and official recognition during his lifetime, leaving behind a complex and influential legacy. His work bridged the declining Neoclassical tradition and the rising tide of Romanticism, eventually incorporating elements of Realism, making him a pivotal, albeit sometimes controversial, figure in art history.

An Auspicious Beginning: Family and Early Training

Horace Vernet's destiny seemed intertwined with art from the moment of his birth. He was born within the walls of the Louvre Palace, which, during the tumultuous early days of the French Revolution, served as a refuge for artists, including his parents. This dramatic entry into the world foreshadowed a life lived amidst historical change and artistic creation. Crucially, Vernet hailed from a distinguished artistic dynasty. His grandfather, Claude-Joseph Vernet, was one of the most celebrated landscape and marine painters of the 18th century, famed for his series Ports of France. His father, Antoine Charles Horace Vernet, known as Carle Vernet, excelled in depicting horses, hunts, and military subjects, particularly cavalry charges, enjoying the patronage of Napoleon Bonaparte himself.

Growing up surrounded by sketches, canvases, and the constant talk of art, Horace naturally absorbed the fundamentals of drawing and painting from a young age, primarily under his father Carle's guidance. The family studio was his first school. While inheriting a deep respect for technical skill and observation from his lineage, Horace sought formal training to refine his craft. Around 1810, he entered the studio of François-André Vincent, a prominent painter who upheld the Neoclassical tradition, albeit with a slightly more painterly touch than his contemporary, the great Jacques-Louis David. This formal education provided Vernet with a solid grounding in academic principles, even as his own temperament and the spirit of the age pulled him towards more dynamic and contemporary subjects.

Navigating Turbulent Times: Early Career and Romantic Connections

Vernet's early career unfolded against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Empire and its eventual collapse, followed by the Bourbon Restoration. His family's Bonapartist leanings, particularly his father's connection to the Emperor, shaped Horace's own political sympathies. He even served briefly in the National Guard during the defence of Paris in 1814. This affinity for the Napoleonic legend would become a recurring theme in his work, appealing to a public nostalgic for the glories of the Empire, but sometimes causing friction with the restored monarchy. Despite this, Vernet was ambitious and pragmatic, seeking recognition through the official Salon exhibitions.

During the 1810s and early 1820s, Vernet began to establish his reputation. He quickly distinguished himself from the staid historical subjects favored by the Neoclassical establishment, turning instead to scenes of contemporary military life, genre subjects, and portraits that captured a sense of immediacy. A pivotal relationship during this period was his close friendship with Théodore Géricault, a leading figure of the burgeoning Romantic movement. They shared a studio for a time and mutually influenced each other. Géricault's dramatic realism and interest in modern subjects, famously exemplified in his Raft of the Medusa (1819), resonated with Vernet's own inclinations. Vernet painted several portraits of his friend, capturing Géricault's intense artistic personality. This connection placed Vernet firmly within the circle of young artists challenging the old guard and embracing the emotional intensity and dynamism of Romanticism.

Chronicler of Conflict: The Military Paintings

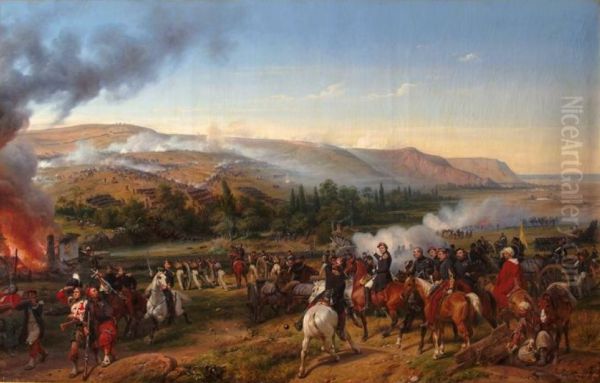

Horace Vernet's most enduring fame rests on his mastery of the battle painting genre. In an era marked by almost continuous warfare, from the Napoleonic campaigns to the French conquest of Algeria and the Crimean War, there was a significant public and official appetite for depictions of military exploits. Vernet rose to meet this demand with unparalleled energy and skill. He moved away from the allegorical or highly idealized battle scenes of earlier periods, pioneered by artists like Charles Le Brun, towards a style that emphasized accuracy, action, and the experiences of the common soldier, building upon the work of Napoleonic-era painters like Antoine-Jean Gros.

His canvases, often vast in scale, teemed with figures, capturing the chaos, drama, and specific details of combat. Works like the Battle of Jemappes and the Battle of Montmirail depicted key moments from the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars with a sense of journalistic immediacy. He didn't shy away from the grim realities of war, as seen in works like The Dog of the Regiment or compositions depicting the aftermath of battle, yet he often imbued his scenes with a sense of national pride and heroism. His ability to render horses in dynamic motion, a skill likely honed under his father Carle, was particularly admired.

Under the July Monarchy, King Louis-Philippe became a major patron, commissioning Vernet to contribute significantly to the Galerie des Batailles (Gallery of Battles) at the Palace of Versailles. This vast project aimed to glorify French military history across the centuries. Vernet produced enormous canvases depicting battles from Fontenoy to Wagram, solidifying his position as the preeminent military painter of his day. Later, during the Second Empire, he continued to chronicle French military endeavors, such as the Crimean War in paintings like the Battle of the Alma. His work defined the visual representation of warfare for a generation.

Capturing Character: Vernet's Portraiture

While renowned for his epic battle scenes, Horace Vernet was also a highly sought-after and accomplished portrait painter. His approach to portraiture reflected his broader artistic style: a blend of accurate likeness, attention to detail (especially in costume and setting), and a certain Romantic flair. He possessed a keen ability to capture the personality and social standing of his sitters, moving beyond mere physical representation.

He painted numerous prominent figures of his time. His patrons included royalty, aristocracy, military leaders, fellow artists, and members of the burgeoning bourgeoisie. Notable subjects included the Duke of Orléans (before he became King Louis-Philippe), members of Napoleon I's family, and later, Emperor Napoleon III. These official portraits often conveyed authority and status, yet Vernet managed to infuse them with a degree of naturalism that distinguished them from the more rigid formality of some Neoclassical portraitists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose emphasis was on linear purity and idealized form.

Vernet's portraits of fellow artists, such as the sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and his friend Théodore Géricault, often reveal a more intimate understanding and psychological depth. His Portrait of Madame Madeleine Mahler showcases his ability to render textures and capture a sense of quiet elegance. Throughout his portrait work, Vernet demonstrated versatility, adapting his style to suit the subject while maintaining a characteristic vibrancy and directness. These works provide invaluable visual records of the key personalities who shaped 19th-century France.

Journeys Eastward: The Orientalist Vision

Like many European artists of the 19th century, Horace Vernet was captivated by the allure of the "Orient" – a term then used broadly to refer to North Africa and the Middle East. France's military campaigns in Algeria, beginning in 1830, provided Vernet with direct access to this region, which he visited multiple times. These travels profoundly impacted his art, leading to a significant body of Orientalist work that contributed significantly to this popular genre. His experiences provided him with firsthand material, differentiating his work from artists who relied solely on second-hand accounts or imagination.

Vernet's Orientalist paintings encompass a range of subjects. He documented French military actions in Algeria, such as The Capture of the Smalah of Abd-el-Kader (a massive, panoramic work) and The Breach of Constantine, depicting these events with his characteristic eye for detail and dramatic composition. However, he also painted scenes of local life, bustling markets, desert landscapes, and Bedouin encampments. He was particularly fascinated by Arab horses and warriors, depicting them in dynamic scenes like Lion Hunt.

His Orientalist works, while based on observation, inevitably reflected the European perspectives and stereotypes of the time. They often emphasized the exotic, the picturesque, and sometimes the violent aspects of the cultures he depicted. Compared to the more sensuous and color-focused Orientalism of Eugène Delacroix, who had visited North Africa earlier, Vernet's approach often retained a stronger narrative and documentary element, aligning with his background in historical and military painting. Other notable Orientalist painters of the era included Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps and Eugène Fromentin, each contributing to the European fascination with these lands through their distinct styles. Vernet's contributions were significant in popularizing these themes.

A Distinctive Style: Technique and Approach

Horace Vernet's artistic style is characterized by its energy, narrative clarity, and a synthesis of different artistic currents. He possessed remarkable technical facility, enabling him to work with extraordinary speed and efficiency. This very speed became part of his legend; he was known to complete large, complex canvases in remarkably short periods. While some critics saw this as a sign of superficiality, others admired his seemingly effortless virtuosity and the resulting sense of spontaneity in his work.

His compositions, especially in the large battle and historical scenes, are typically dynamic and filled with movement. He skillfully organized large numbers of figures, horses, and landscape elements into coherent and dramatic narratives. His drawing was confident and descriptive, capturing anatomical accuracy and the details of uniforms, weaponry, and architecture. While grounded in the academic tradition learned from Vincent, his brushwork was often looser and more expressive than that of strict Neoclassicists, contributing to the vitality of his surfaces.

Vernet had a keen eye for dramatic lighting effects, often using strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to heighten the emotional impact of his scenes, particularly in his battle paintings and Orientalist works. His color palette was generally rich and varied, though perhaps less purely focused on color for its own sake than Delacroix's. His ability to render the textures of fabrics, metal, and animal hides was exceptional. Ultimately, his style represented a pragmatic and highly effective blend of academic training, Romantic sensibility, and a Realist's attention to observable detail, perfectly suited to the historical and contemporary subjects he favored.

Accolades and Academia: Influence and Official Roles

Horace Vernet's talent and productivity brought him considerable success and official recognition throughout his career. He navigated the shifting political landscapes of France adeptly, securing patronage from successive regimes. His popularity with the public was immense, and his works were widely reproduced through engravings, further spreading his fame. King Louis-Philippe was a particularly important patron, not only commissioning works for Versailles but also appointing Vernet Director of the French Academy in Rome.

Vernet held the prestigious post of Director of the French Academy in Rome from 1829 to 1834. This position placed him at the head of the most important French artistic institution outside of Paris, responsible for mentoring the young winners of the Prix de Rome. His directorship was generally seen as successful, marked by a less rigid approach than some of his predecessors. He encouraged students while maintaining the Academy's standards, and his own continued artistic production served as an example. His influence extended through the many students who passed through the Academy during his tenure and through his broader impact on the Paris Salon.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent generations of military and historical painters, such as Ernest Meissonier, known for his meticulously detailed small-scale historical scenes, and Jean-Léon Gérôme, although Gérôme was more directly a student of Paul Delaroche. Vernet's success demonstrated the viability of large-scale historical and contemporary subjects, and his Orientalist works contributed significantly to the development of that genre. He was elected to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1826, cementing his place within the official art establishment.

Anecdotes and the Man

Beyond his artistic achievements, anecdotes surrounding Horace Vernet offer glimpses into his personality, suggesting a character as vibrant and dynamic as his paintings. His very birth in the Louvre during the Revolution provides a dramatic opening chapter. Accounts depict him as energetic, confident, and possessing a sense of humor, sometimes bordering on the theatrical.

One famous, though possibly apocryphal, story reported in the New York Times tells of Vernet traveling by train. Annoyed by two women loudly discussing him, he supposedly waited until the train entered a dark tunnel and then kissed the back of his own hand loudly twice, leading the women to accuse each other upon emerging into the light. Another tale, reported in the Birmingham Daily Journal, describes him being similarly scrutinized by two English ladies in a carriage, a situation he reportedly found amusing rather than insulting.

While the veracity of such tales can be debated, they contribute to the image of Vernet as a man comfortable in the public eye, perhaps even enjoying the attention his fame brought. His prolific output and ability to manage large-scale commissions suggest immense energy and discipline. His friendships, like the one with Géricault, indicate a capacity for connection within the artistic community. He was, by all accounts, a prominent figure not just in the studio but in the social and cultural life of Paris.

Reception Through Time: Criticism and Legacy

Horace Vernet enjoyed enormous popularity and critical acclaim for much of his career. He received numerous state commissions, prestigious appointments, and honors. His paintings were eagerly anticipated at the Salons, and his ability to capture moments of national history resonated deeply with the public. Patrons like King Louis-Philippe and Emperor Napoleon III valued his ability to create grand narratives that glorified France and its rulers. His technical skill was widely acknowledged, even by those who were not entirely sympathetic to his style.

However, Vernet also faced significant criticism, most famously from the poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire. Baudelaire, a champion of Delacroix and the more subjective aspects of Romanticism, found Vernet's work lacking in deep artistic feeling and imagination. He famously dismissed Vernet as a "military man who paints" rather than a true artist, criticizing his work as overly literal, anecdotal, and akin to journalism or popular illustration ("a stenographer of history"). Baudelaire saw Vernet's facility and popularity as signs of artistic compromise rather than genius, accusing him of catering to popular taste instead of pursuing higher artistic ideals. Other critics sometimes found his compositions chaotic or his historical interpretations superficial.

After his death, Vernet's reputation declined somewhat, particularly with the rise of Impressionism and subsequent modernist movements, which valued different artistic qualities. His detailed, narrative style seemed outmoded compared to the focus on light, color, and subjective perception. However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a reassessment of his work. Exhibitions and scholarly research have highlighted his technical brilliance, his importance as a historical witness, his role in the development of Orientalism, and his position as a key transitional figure between Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and Realism. Today, his works are prominently displayed in major museums, including the Louvre, the Palace of Versailles, and the Wallace Collection in London, recognized for their historical significance and artistic merit. Other prominent historical painters of his time, like Paul Delaroche, faced similar shifts in critical fortune, highlighting the changing tastes that define art history. Vernet's legacy remains that of a highly skilled, incredibly productive, and historically significant painter who captured the spirit of his age.

Conclusion: An Enduring Chronicle in Paint

Horace Vernet's contribution to French art is undeniable. As the scion of an artistic dynasty, he inherited a tradition of technical skill, but forged his own path, becoming one of the most successful and recognizable painters of the 19th century. His vast canvases depicting battles from the Revolutionary Wars to the Crimean War served as powerful visual narratives for a nation grappling with its recent past and ongoing military endeavors. His portraits captured the likenesses and characters of the era's key figures, while his Orientalist scenes fed a growing European fascination with distant lands, informed by his own travels.

Though criticized by some contemporaries like Baudelaire for a perceived lack of artistic depth, Vernet's ability to synthesize elements of Romanticism and Realism, his narrative clarity, his technical facility, and his sheer productivity were widely admired. He served as Director of the French Academy in Rome, influenced numerous artists, and enjoyed extensive official patronage. His life and work reflect the turbulent history and complex artistic currents of 19th-century France. Today, Horace Vernet is recognized not just as a master technician or a popular chronicler, but as a significant artist whose work provides invaluable insight into the visual culture, historical consciousness, and artistic transitions of his time. His paintings remain compelling testaments to an era of dramatic change, rendered with energy, detail, and enduring impact.