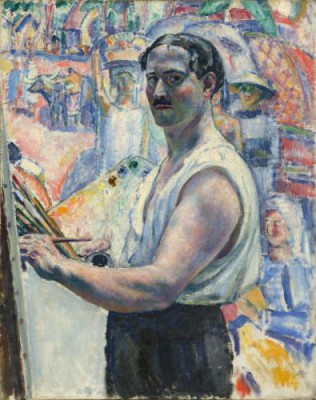

Augustin Carrera stands as a fascinating, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of early 20th-century European art. Born in Madrid in 1878 to French parents, his life and career bridged geographical and artistic boundaries, reflecting a period of immense change and innovation. A painter of considerable talent and versatility, Carrera navigated the currents of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the burgeoning modern movements, forging a distinct path characterized by rich color, expressive technique, and a deep engagement with both the figure and the landscape. His journey from the academic studios of Spain and France to the sun-drenched vistas of Provence and the exotic allure of Indochina reveals an artist constantly seeking, absorbing, and reinterpreting the world around him.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Augustin Carrera's artistic journey began in Madrid, the city of his birth. Despite his French parentage, his initial artistic sensibilities were undoubtedly shaped by the rich cultural heritage of Spain, a land that had produced masters like Velázquez, Goya, and later, Picasso and Dalí. From a young age, Carrera exhibited a precocious talent for drawing and painting, a gift that his family appears to have encouraged. This early promise led him to seek formal instruction, a crucial step for any aspiring artist of that era.

His foundational training took place under the tutelage of respected artists. In Marseille, he studied with Alphonse Moutte (1840-1913), a prominent painter of the Provençal school known for his landscapes and genre scenes. Moutte, himself a student of Ernest Meissonier, would have instilled in Carrera a solid grounding in academic technique, emphasizing draftsmanship and a faithful representation of nature. This period in Marseille was significant, as it likely provided Carrera with his first deep immersion in the light and landscapes of Southern France, a region that would later become central to his artistic identity.

Seeking to further refine his skills and broaden his artistic horizons, Carrera moved to Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the art world at the time. There, he enrolled in the studio of Léon Bonnat (1833-1922) at the École des Beaux-Arts, or a similar prestigious institution like the Académie Julian which often had instructors from the École. Bonnat was a towering figure in French academic art, renowned for his portraiture and historical paintings. A staunch advocate of traditional methods, Bonnat emphasized rigorous drawing, anatomical accuracy, and a sober, realistic palette, drawing inspiration from Spanish Golden Age painters like Ribera and Velázquez. Studying under Bonnat would have exposed Carrera to the highest standards of academic painting, providing him with a technical mastery that would serve as a bedrock for his later, more expressive explorations. The influence of Bonnat's Spanish affinities might have also resonated with Carrera's own Spanish birth.

Despite the rigorous academic training, Carrera, like many artists of his generation, was not immune to the revolutionary artistic currents swirling through Paris. The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of unprecedented artistic ferment, with Impressionism having already challenged academic conventions, and Post-Impressionism pushing the boundaries of color, form, and expression even further.

Influences and the Development of a Personal Style

While his academic training provided a strong technical foundation, Augustin Carrera's artistic vision was profoundly shaped by the Post-Impressionist masters. He absorbed lessons from a pantheon of innovators, whose work represented a decisive break from purely mimetic representation towards more subjective and expressive interpretations of reality.

Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) was a particularly crucial influence. Cézanne's methodical deconstruction of form into geometric essentials, his emphasis on the underlying structure of objects and landscapes, and his revolutionary approach to perspective offered a new way of seeing and painting. Carrera would have studied Cézanne's treatment of Provençal landscapes, particularly the iconic Mont Sainte-Victoire, learning how to convey volume and space through carefully modulated color planes rather than traditional chiaroscuro. This structural integrity, derived from Cézanne, likely informed Carrera's own landscape compositions, lending them a solidity and thoughtful construction.

The vibrant, emotionally charged color palettes of Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) also left an indelible mark. Van Gogh's passionate brushwork and his use of color to convey intense subjective experience resonated with artists seeking to move beyond mere visual transcription. Gauguin's Synthetism, with its emphasis on flat planes of bold color, strong outlines, and symbolic content, offered another path away from naturalism. Carrera's own works, particularly his landscapes and some figurative pieces, often exhibit a heightened chromatic intensity and an expressive handling of paint that echo these Post-Impressionist pioneers. He learned to use color not just descriptively but also emotionally and decoratively.

The Impressionists, too, played a role in his development. The work of Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) would have exposed him to the importance of capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, the practice of en plein air painting, and a brighter, more luminous palette. While Carrera's style evolved beyond strict Impressionism, the lessons learned from their observation of natural light remained pertinent, especially in his landscape paintings.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917), with his unconventional compositions, his interest in capturing modern life, and his mastery of line, offered another important point of reference. Degas's ability to combine classical draftsmanship with a modern sensibility might have appealed to Carrera, who was himself navigating the space between tradition and innovation. The influence of Georges Seurat (1859-1891) and Pointillism, with its systematic application of color, might also have been a component in Carrera's understanding of color theory and its optical effects, even if he didn't adopt the technique wholesale.

Even the nascent Cubist explorations of Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Georges Braque (1882-1963), emerging in the first decade of the 20th century, would have been part of the artistic discourse in Paris. While Carrera did not become a Cubist, the intellectual rigor and formal experimentation of such movements contributed to an environment where artists felt empowered to challenge established norms. Carrera's work, therefore, became a synthesis of these diverse influences, filtered through his own temperament and artistic goals. He sought to combine the structural solidity of Cézanne with the expressive color of Van Gogh and Gauguin, all underpinned by the draftsmanship he had honed in academic studios.

The Provençal Connection and Decorative Works

Augustin Carrera developed a strong affinity for Provence, a region whose luminous light, vibrant colors, and dramatic landscapes had already captivated artists like Cézanne and Van Gogh. His earlier studies in Marseille under Alphonse Moutte, a key figure in the Provençal school, likely laid the groundwork for this connection. The Provençal school, while diverse, generally emphasized the unique character of the region, often employing bright palettes and expressive brushwork.

Carrera became an active participant in this artistic milieu. He is known to have collaborated with other painters of the Provençal school on large-scale decorative projects. These collaborations were common at the time, particularly for public commissions or large private residences. Such projects often involved creating monumental frescoes or decorative panels, requiring a blend of artistic skill and an understanding of architectural space. While specific names of his collaborators on these Provençal projects are not always readily available in general surveys, the environment would have included artists who shared an interest in capturing the essence of the region, possibly figures associated with Fauvism or its regional interpretations, such as Auguste Chabaud or René Seyssaud, who were also deeply connected to the Provençal landscape.

His involvement in decorative arts extended beyond Provence. Carrera designed decorative panels for the Colonial Ministry in Paris. This commission highlights his ability to work on a grand scale and to adapt his style to official requirements, which often favored allegorical or symbolic representations. Such commissions were prestigious and provided artists with significant visibility.

Furthermore, he designed a stage curtain for the Marseille Opera. Theatrical design was another avenue for artists to engage with large-scale decorative work, requiring a flair for drama and an understanding of how visual elements would read from a distance. These projects underscore Carrera's versatility and his reputation as an artist capable of handling ambitious and complex commissions. His style in these decorative works likely combined his strong sense of color and composition with a more formal, perhaps even classicizing, approach suitable for public and official spaces.

The Journey to Indochina and its Impact

A pivotal moment in Augustin Carrera's career came in 1912 when he received a prestigious scholarship, the Prix de l'Indochine, which enabled him to travel to French Indochina (encompassing modern-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia). This journey marked a significant turning point, exposing him to entirely new landscapes, cultures, and artistic traditions. For a European artist, the "Orient" held a powerful allure, promising exotic subjects and a different quality of light and color.

Carrera spent a considerable time in the region, immersing himself in its unique atmosphere. He produced numerous works depicting the landscapes, people, and daily life of Indochina. These paintings and sketches would have been characterized by a heightened sensitivity to the tropical environment – the lush vegetation, the vibrant markets, the ancient temples, and the distinctive quality of light. This experience likely pushed his palette in new directions, encouraging even bolder and more exotic color harmonies. Artists like Gauguin had already demonstrated the transformative impact of non-European cultures on Western art, and Carrera's journey can be seen in this tradition of seeking fresh inspiration beyond the confines of Europe.

The most significant commission arising from his time in Indochina was the creation of monumental frescoes for the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in 1928. This was a major undertaking, attesting to the high regard in which his work was held. Decorating a royal palace required not only artistic skill but also diplomatic sensitivity and an ability to work within a specific cultural context. These frescoes likely depicted scenes from Cambodian history, mythology, or royal life, and would have been a remarkable fusion of Carrera's European artistic training with the thematic and aesthetic requirements of his Cambodian patrons. This project stands as a unique achievement in his oeuvre, setting him apart from many of his European contemporaries.

The Indochina experience had a lasting impact on Carrera's art. Even after returning to Europe, the themes, colors, and compositional ideas gleaned from his time in the East likely continued to inform his work. It broadened his visual vocabulary and provided him with a rich store of imagery that he could draw upon for years to come.

Wartime, Montparnasse, and Continued Artistic Production

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 inevitably disrupted Augustin Carrera's life and career, as it did for countless artists across Europe. He was conscripted into military service in 1914. However, his time at the front was cut short; he was wounded and subsequently discharged from active duty in 1915. This wartime experience, though brief, would have been a stark contrast to the creative pursuits of his artistic life.

After his recovery, Carrera made a decisive move to Paris, settling in the Montparnasse district. By this time, Montparnasse had supplanted Montmartre as the vibrant heart of artistic and intellectual life in Paris, attracting a diverse international community of painters, sculptors, writers, and poets. It was a melting pot of creativity, where artists from across Europe and beyond congregated in cafés like Le Dôme, La Rotonde, and Le Select, exchanging ideas and forging new artistic paths.

Living and working in Montparnasse placed Carrera at the center of this dynamic environment. He would have been surrounded by artists pushing the boundaries of modernism, figures such as Amedeo Modigliani, Chaïm Soutine, Moïse Kisling, Tsuguharu Foujita, Constantin Brâncuși, and many others. While Carrera maintained his own distinct artistic voice, the stimulating atmosphere of Montparnasse undoubtedly fueled his creative energies and kept him engaged with contemporary artistic developments. He became an integral part of this "School of Paris," a term used to describe the eclectic group of foreign-born artists who flocked to the French capital.

Throughout this period, Carrera continued to be a prolific painter. His subject matter remained diverse, encompassing landscapes, portraits, nudes, and still lifes. His style, while rooted in the Post-Impressionist tradition, likely continued to evolve, absorbing subtle influences from the artistic ferment around him without succumbing to fleeting trends. He maintained a commitment to strong composition, expressive color, and a painterly application of pigment.

Major Works, Themes, and Artistic Style

Augustin Carrera's oeuvre is characterized by its versatility and a consistent engagement with certain key themes, all rendered in a style that balanced expressive freedom with underlying formal rigor.

Landscapes: Landscapes formed a significant portion of Carrera's output. Whether depicting the sun-drenched fields of Provence, the exotic vistas of Indochina, or other locales, his landscapes are notable for their vibrant color and dynamic compositions. He moved beyond the purely observational approach of the Impressionists, imbuing his scenes with a strong sense of place and often an emotional resonance. His brushwork could be vigorous and textured, conveying the energy of the natural world. The influence of Cézanne is often discernible in the structural solidity of his landscapes, while the heightened palette can recall Van Gogh or Gauguin.

Nudes: Carrera was also known for his depictions of the female nude. These works are often described as sensual and possessing a sculptural quality. He approached the nude not merely as an academic exercise but as a vehicle for exploring form, line, and the expressive potential of the human body. His nudes likely varied in style, some perhaps showing a more classical influence inherited from Bonnat, others displaying a more modern sensibility in their simplification of form or their bold use of color. These works would have engaged with a long tradition in Western art, from Titian and Rubens to Ingres and Manet, each artist bringing their own interpretation to the subject.

Still Lifes: The still life genre also featured in Carrera's work. A notable example is his "Still Life with Turkey and Rum Bottle" (Nature morte à la dinde et bouteille de rhum), painted around 1920. This work, like many still lifes, would have allowed Carrera to focus on composition, color relationships, and the textures of objects in a controlled studio environment. Still life painting, with its rich history from Dutch Golden Age masters to Chardin and Cézanne, offered artists a space for formal experimentation. Carrera's approach likely combined a realistic depiction of objects with an expressive use of paint and color, transforming everyday items into subjects of aesthetic contemplation.

Decorative and Monumental Works: As previously discussed, Carrera's monumental frescoes for the Cambodian Royal Palace and his decorative panels for the Colonial Ministry represent significant achievements. These large-scale projects demonstrate his ability to adapt his style to different contexts and to work on an ambitious public scale. His design for the Marseille Opera curtain further underscores this capacity. These works often required a more formal and perhaps allegorical approach than his easel paintings.

Overall Style: Carrera's style can be broadly characterized as Post-Impressionist, but with a distinctive personal inflection. He valued strong drawing and composition, a legacy of his academic training. However, he combined this with a modern sensibility for color, often using it boldly and expressively rather than purely naturalistically. His brushwork was typically confident and visible, contributing to the texture and dynamism of his paintings. He was not an avant-garde radical in the vein of the Cubists or Dadaists, but rather an artist who skillfully synthesized tradition with the innovations of his time, creating works that were both aesthetically pleasing and emotionally engaging.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Official Acclaim

Augustin Carrera was an active participant in the Parisian art scene, regularly exhibiting his work in prestigious salons and galleries. These exhibitions were crucial for an artist's visibility, reputation, and commercial success. He showcased his paintings at the Salon des Tuileries, a major annual exhibition that emerged as an alternative to the more conservative official Salon. He also exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français, one of the most established and traditional venues, suggesting his ability to appeal to a range of tastes.

His participation in the Salon des Indépendants is also significant. Founded by artists like Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Albert Dubois-Pillet, the Indépendants operated on a "no jury, no awards" principle, providing a platform for more avant-garde and experimental art. Carrera's presence here indicates his engagement with more progressive artistic circles. Furthermore, he exhibited at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs and the Musée de Montparnasse, venues that would have highlighted different facets of his work, from decorative arts to his connection with the Montparnasse artistic community.

A notable moment of recognition came at the 1937 International Exposition in Paris (Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne), where Carrera was awarded a gold medal for his work. This was a significant honor, as international expositions were major cultural events that attracted global attention. Such an award would have solidified his reputation and brought his art to a wider audience.

His artistic contributions also received official state recognition. Augustin Carrera was awarded the Legion of Honour (Légion d'honneur), France's highest order of merit. He was first made a Chevalier (Knight) and later, in 1928, promoted to Officier (Officer) of the Legion of Honour. This distinction was a testament to his standing in the French art world and acknowledged his significant contributions to French culture, likely recognizing his work on official commissions, his international achievements (such as the Cambodian frescoes), and his overall artistic merit. The art critic François Thibault-Sisson (often cited as Thibault-Sienczyk in some sources), writing for prominent newspapers like Le Temps, regularly reported on Carrera's work, further contributing to his public profile and critical reception.

The support of influential patrons was also important. Carrera is noted to have had a close relationship with Albert Sarraut, a prominent French politician who served multiple times as Governor-General of French Indochina and held various ministerial posts. Sarraut was also a known art collector. Such a connection would have been invaluable, potentially leading to commissions (perhaps even facilitating the Cambodian Palace project) and providing a network of support within influential circles.

Later Life and Legacy

Augustin Carrera continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, remaining a respected figure in the French art world. He passed away in 1952, leaving behind a substantial body of work that reflects the diverse artistic currents of his time. While he may not have achieved the household-name status of some of his more radically innovative contemporaries like Picasso or Matisse, his contribution is significant.

Carrera's legacy lies in his skillful synthesis of tradition and modernity. He successfully navigated the transition from 19th-century academicism to the more expressive and subjective modes of 20th-century art. His work demonstrates a deep understanding of color, form, and composition, applied across a range of subjects and scales. His landscapes capture the essence of the places he depicted, from the familiar light of Provence to the exotic allure of the East. His nudes and figurative works show a sensitivity to the human form, while his still lifes reveal a thoughtful engagement with the everyday.

His involvement in large-scale decorative projects, particularly the Cambodian Royal Palace frescoes, marks a unique aspect of his career, showcasing his ability to work monumentally and cross-culturally. The official recognition he received, including the Legion of Honour, attests to the esteem in which he was held during his lifetime.

Today, Augustin Carrera's paintings can be found in private collections and occasionally appear at auction. For art historians and enthusiasts, his work offers a valuable perspective on a period of rich artistic exploration. He represents a cohort of artists who, while not always at the cutting edge of the avant-garde, played a crucial role in developing and disseminating new artistic ideas, creating a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically rewarding. His art serves as a reminder of the diverse paths taken by artists in the early 20th century and the enduring power of painting to capture and interpret the world. His journey from Madrid to Paris, Provence, and Indochina is a testament to a life dedicated to art, marked by a constant search for beauty and expression.