Augustus Osborne Lamplough stands as a notable figure within the British Orientalist movement, an artist whose watercolours captured the unique atmosphere and landscapes of North Africa and the Middle East with remarkable sensitivity. Born in Manchester, England, in 1877, Lamplough's life and career spanned a period of intense European fascination with the 'Orient'. He developed a distinctive style, primarily using watercolour, that focused on the interplay of light, space, and subtle colour to evoke the serene, and sometimes melancholic, beauty of the lands he depicted. His death in 1930 marked the end of a career dedicated to translating the visual poetry of distant landscapes onto paper.

Lamplough is recognized as one of the significant representatives of the later phase of British Orientalism. His work contributed to the rich tapestry of images that shaped the European perception of Egypt, Morocco, and Algeria during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was not merely a topographical painter; his works often carried an emotional weight, reflecting perhaps the sensibilities of the Victorian and Edwardian eras from which he emerged.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Details of Lamplough's earliest years trace back to Manchester, a major industrial hub of Victorian England. His formal artistic training took place at the Chester School of Art. This foundational education would have provided him with the essential skills in drawing and painting that he would later refine to such a high degree. Following his studies, Lamplough embarked on an academic path within the arts.

In 1898, he took up a position as a lecturer at the Leeds College of Art. This role indicates a certain level of mastery and recognition early in his career. During this initial phase, his artistic interests were reportedly focused closer to home, or at least within European settings. Sources suggest that his earlier works often depicted Venetian interiors and scenes, a popular subject for British artists drawn to the history and unique light of the Italian city. This early focus highlights a competence in architectural rendering and interior atmosphere that would later inform his depictions of North African settings.

The Pivotal Journey to North Africa

A significant turning point in Lamplough's artistic trajectory occurred around 1905. It was during this period that he undertook his first major visit to North Africa. This journey proved transformative, fundamentally shifting his thematic focus and solidifying his place within the Orientalist tradition. The landscapes, the quality of light, the architecture, and the cultures he encountered in regions like Egypt, Morocco, and Algeria captivated his imagination.

Following this initial immersion, Lamplough's art became predominantly dedicated to capturing the essence of these lands. The canals and palaces of Venice gave way to the sun-drenched deserts, the majestic Nile River, the enduring pyramids, and the vibrant life of North African towns and encampments. This shift was not merely a change of subject matter but a profound reorientation of his artistic vision, driven by the powerful allure of the 'Orient'. His subsequent travels would continue to fuel this passion, providing him with a rich repository of scenes and experiences to draw upon.

Mastery of Watercolour Technique

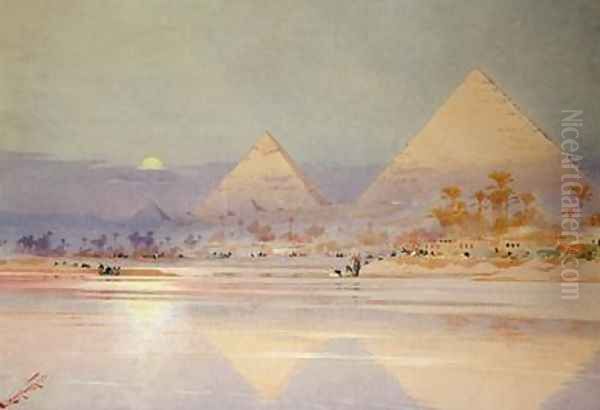

Lamplough's chosen medium was primarily watercolour, and his mastery of it is central to his artistic identity. He possessed an exceptional ability to manipulate this often-challenging medium to achieve effects of great subtlety and luminosity. His watercolours are characterized by their delicate washes, transparent layers, and nuanced colour palettes. He excelled at capturing the specific qualities of light found in North Africa – the hazy heat of midday, the soft glow of dawn, or the dramatic colours of sunset over the desert or the Nile.

His technique allowed for both precision and atmospheric effect. While capable of rendering architectural details or the forms of figures and camels with clarity, his primary focus often seemed to be on the overall mood and the play of light across surfaces. The transparency inherent in watercolour was used to great effect, creating a sense of airiness and depth. This technical finesse distinguishes his work and aligns perfectly with the often ethereal and tranquil nature of the scenes he chose to depict.

Unique Compositional Style

Beyond his technical skill, Lamplough developed a distinctive approach to composition that sets his work apart. A recurring feature in many of his paintings is the deliberate minimizing of the main subject – be it figures, boats, or even architectural landmarks like the pyramids – within the overall frame. He often dedicated a significant portion of the canvas to the sky, the water, or the expanse of the desert.

This compositional strategy serves a specific purpose: it enhances the sense of scale, space, and atmosphere. By reducing the prominence of the nominal subject, Lamplough draws the viewer's attention to the vastness and stillness of the surrounding environment. This creates a feeling of profound tranquility, sometimes tinged with a sense of solitude or timelessness. This approach was noted as somewhat uncommon among his contemporaries, suggesting a unique artistic sensibility focused on evoking feeling through spatial arrangement rather than solely through narrative detail.

Evoking Mood and Atmosphere

Lamplough's paintings are more than just accurate representations; they are imbued with a palpable mood. The combination of his delicate watercolour technique and his spacious compositions often results in works that feel serene, contemplative, and deeply atmospheric. There is frequently a quietness, a sense of suspended time, that pervades his scenes, particularly those depicting the Nile or the desert at dawn or dusk.

Some interpretations suggest his work carries an undercurrent of melancholy or nostalgia. This could be seen as a reflection of the broader Victorian and Edwardian cultural mood, a wistfulness for perceived simpler times or distant, romanticized lands in an era of rapid industrialization and change. Whether intentional or intuitive, this emotional resonance adds depth to his landscapes, inviting the viewer not just to see a place, but to feel its essence. His handling of light is crucial here, often soft and diffused, contributing to the dreamlike or meditative quality of the work.

Key Themes: Egypt and Beyond

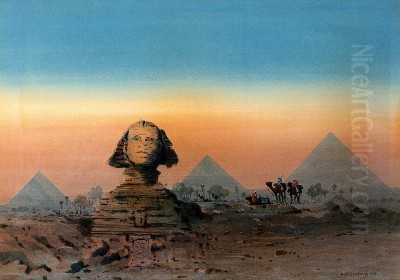

Egypt was arguably Lamplough's most significant and recurring source of inspiration. The Nile River, in particular, features prominently in his oeuvre. He depicted it in various conditions – calm and reflective under a soft sky, bustling with feluccas (traditional sailboats), or bordered by palm trees and ancient ruins. The pyramids of Giza were another favourite subject, often shown rising majestically from the desert sands, sometimes silhouetted against a dramatic sunset sky, as seen in his well-known work The Pyramids at Dusk.

The vast expanse of the desert also captivated him. He painted scenes of Bedouin encampments, camel trains traversing the dunes (Bedouin crossing the desert, Camel Train on the Nile, Arab Camels Surveying the Desert at Dusk), and the subtle shifts of colour and light across the sands. While Egypt was central, his travels also took him to other parts of North Africa, including Morocco and Algeria, and scenes from these regions also appear in his body of work, showcasing bustling marketplaces or distinct architectural styles. His focus remained consistently on landscape and atmosphere, often including figures primarily to provide scale and context.

Lamplough in the Context of British Orientalism

Augustus Osborne Lamplough worked within a well-established tradition of British Orientalist painting. This movement, which gained momentum throughout the 19th century, saw numerous artists travel to North Africa and the Middle East, drawn by a complex mix of colonial interest, romantic escapism, archaeological curiosity, and a desire for new, exotic subject matter. These artists documented landscapes, ancient ruins, and local customs, often filtering their observations through a European lens.

Lamplough's work sits alongside that of other prominent British artists associated with Orientalism. The pioneering David Roberts (1796-1864), famous for his detailed lithographs of Egypt and the Holy Land, set a high standard for topographical accuracy combined with romantic grandeur. John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876) was renowned for his incredibly detailed depictions of domestic life and interiors in Cairo, often executed with meticulous watercolour and bodycolour technique.

Edward Lear (1812-1888), known for his nonsense verse but also a prolific travel artist, created numerous atmospheric watercolour sketches and oil paintings during his extensive travels, including trips to Egypt and the Near East. William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), a key figure in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, also travelled to the Middle East, seeking authenticity for his religious paintings, and produced striking landscapes like The Scapegoat.

Other contemporaries or near-contemporaries exploring similar themes included Frederick Goodall (1822-1904), who specialized in large-scale Egyptian subjects; Carl Haag (1820-1915), a German-born artist who settled in England and became known for his detailed watercolours of Middle Eastern scenes; and Frank Dillon (1823-1909), who painted extensively in Egypt and Japan. The Scottish artist Arthur Melville (1855-1904) developed a bold, impressionistic watercolour style applied to scenes from Spain, North Africa, and the Middle East. Earlier figures like William James Müller (1812-1845) and Thomas Seddon (1821-1856) also made significant contributions with their Levantine landscapes. Even the troubled genius Richard Dadd (1817-1886) produced intricate Orientalist fantasies, albeit often from memory or imagination during his confinement.

Relationships with Contemporaries: Cooperation and Competition

The artistic landscape Lamplough inhabited was one of both shared interests and inevitable competition. While direct records of collaboration or specific rivalries involving Lamplough are scarce according to the provided sources, the context suggests likely interactions. Artists within the Orientalist circle would have been aware of each other's work through exhibitions, publications, and shared networks.

The overlap in subject matter, particularly Egyptian scenes, meant Lamplough was working in territory also famously covered by artists like David Roberts. While Roberts's style, often focused on detailed architectural rendering and sometimes grander historical or religious connotations, differed from Lamplough's more atmospheric watercolour approach, they would have appealed to a similar audience interested in depictions of Egypt. This overlap naturally implies a degree of market competition.

Similarly, while Edward Lear's overall output was broader (including ornithological illustration and literature), his landscape watercolours from the region shared a common ground with Lamplough's focus. The sources explicitly state no direct evidence of cooperation or specific competition between Lamplough and Lear, or Lamplough and Roberts, was found. However, it's reasonable to assume they moved within interconnected artistic circles, potentially influencing or reacting to one another's interpretations of the shared Orientalist themes. The similarity in subject matter with William Henry Hunt (the watercolourist, 1790-1861, known for still lifes but also some landscapes) might also be noted, though Hunt belonged to an earlier generation.

Artistic Challenges and Interpretations

The pursuit of artistic vision often involves overcoming challenges, both technical and conceptual. While specific anecdotes about Lamplough's personal struggles in creation are not detailed in the provided sources, the nature of his work suggests inherent difficulties. Achieving the delicate effects of light and atmosphere in watercolour requires immense control and precision. The medium is notoriously unforgiving, demanding confidence and skill.

One source mentions a challenge faced by someone imitating Lamplough's style using photography and gauze to soften the image – the gauze texture interfering with the photo. This indirectly highlights the unique, hard-to-replicate quality of Lamplough's watercolour surfaces. More generally, artists like Lamplough, striving to capture the essence of a place while also imbuing it with personal feeling or a specific mood, constantly navigate the balance between observed reality and artistic interpretation. The desire for accuracy, noted in the context of other artists sometimes discarding works due to imperfections, speaks to the high standards prevalent in representational art of the period. Lamplough's consistent output suggests a successful navigation of these challenges.

Recognition, Patronage, and Legacy

Augustus Osborne Lamplough achieved a notable level of recognition during his lifetime and afterwards. His works were exhibited in both the United Kingdom and the United States, indicating an international reach for his art. His paintings found favour among distinguished patrons, including members of the British Royal Family, specifically King Edward VII and Princess Alexandra (later Queen Alexandra). Royal patronage was a significant mark of success for an artist in this era.

His work continues to be appreciated in the art market. Auction records show his paintings achieving prices ranging from modest sums to significant figures (cited as $64 to $14,176 in the source material, reflecting a wide range depending on size, quality, and period). This demonstrates a sustained interest among collectors. Furthermore, the inclusion of his work, such as The Pyramids at Dusk, in institutional collections like the Wellcome Library in London, ensures its preservation and accessibility for study.

His importance within the Orientalist genre is acknowledged in art historical resources, including online databases and platforms like Wikipedia, solidifying his legacy. While perhaps not possessing the household name status of some absolute giants of Victorian art, Lamplough holds a secure place as a skilled and evocative interpreter of North African landscapes. His contribution lies in his sensitive watercolour technique, his unique compositional sense emphasizing atmosphere, and his consistent dedication to capturing the light and mood of the 'Orient'.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Augustus Osborne Lamplough remains a compelling figure in the history of British watercolour painting and Orientalism. His art offers a window into the landscapes and perceived atmosphere of North Africa and the Middle East as seen through the eyes of an early 20th-century European artist. His technical proficiency in watercolour allowed him to render scenes with a delicate luminosity, while his characteristic compositions created a profound sense of space and tranquility.

His paintings, from the serene stretches of the Nile to the sun-baked expanse of the desert dominated by ancient monuments, continue to resonate with viewers. They capture not just the physical appearance of these locations, but also an emotional quality – a blend of wonder, stillness, and perhaps a touch of wistful nostalgia. As a significant contributor to the Orientalist movement, Lamplough's work provides valuable visual documentation and artistic interpretation, securing his legacy as a master of atmospheric landscape painting. His evocative watercolours remain a testament to his unique vision and his ability to capture the elusive light of the Orient.