Marc Alfred Chataud (1833-1908) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French Orientalist painting. A dedicated artist whose career largely unfolded against the backdrop of colonial Algeria, Chataud's work offers a fascinating window into the European perception and artistic representation of North Africa. His paintings, characterized by a sensitive realism and an appreciation for the nuances of Algerian life and landscape, contributed significantly to the visual culture of Orientalism and established him as a key founder of the Algiers School of Orientalism.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Marseille, France, in 1833, Marc Alfred Chataud's artistic inclinations emerged in a vibrant port city that had long served as a gateway to the Mediterranean and beyond. His initial artistic training took place in his hometown under the tutelage of Emile Loubon (1809-1863), a prominent painter of the Provençal School. Loubon, known for his landscapes and genre scenes, likely instilled in Chataud a foundational appreciation for direct observation and the depiction of regional character. Marseille, with its bustling harbor and diverse population, would have provided ample early inspiration for an aspiring artist.

Seeking to further hone his skills, Chataud later moved to Paris, the undisputed art capital of the 19th century. There, he entered the prestigious studio of Charles Gleyre (1806-1874). Gleyre, a Swiss-born artist who had himself traveled to the Eastern Mediterranean, was an influential teacher. His atelier attracted a remarkable array of students who would go on to achieve great fame, including future Impressionists such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille. While Chataud's artistic path would diverge significantly from that of his Impressionist contemporaries, his time in Gleyre's studio would have exposed him to rigorous academic training, a focus on composition, and perhaps, Gleyre's own Orientalist interests.

During his formative years, particularly in Marseille, Chataud was also reportedly inspired by the works of other painters active in the region who tackled similar themes. Artists like Fabius Brest (1823-1900), known for his detailed views of Constantinople and other Eastern cities, and Alexandre Jean-Baptiste Brun (1853-1941), who also painted Mediterranean and Orientalist scenes, may have further fueled Chataud's interest in subjects beyond the traditional European canon. This early exposure to Orientalist themes in his native South of France, coupled with his formal Parisian training, laid the groundwork for his future specialization.

The Allure of the Orient: Journey and Settlement in Algeria

The 19th century witnessed an explosion of European interest in the "Orient"—a term then broadly encompassing North Africa, the Middle East, and sometimes even parts of Asia. This fascination was fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel, archaeological discoveries, and romantic literature. For artists, the Orient offered a perceived escape from the perceived greyness of industrializing Europe, promising exotic subjects, vibrant colors, and a different quality of light. Algeria, which France had begun colonizing in 1830, became a particularly popular destination for French artists.

Marc Alfred Chataud was among those drawn to its shores. The exact date of his first journey to Algeria is not definitively established, but his artistic focus increasingly shifted towards North African subjects. Eventually, he made the significant decision to settle in Algeria, establishing his home near M'Soud in the southern part of the country. This long-term residency distinguished him from many of his contemporaries who made only fleeting trips. Living in Algeria allowed Chataud to gain a more intimate and sustained understanding of the local culture, landscapes, and people, which is reflected in the nuanced realism of his work.

His decision to immerse himself in Algerian life was pivotal. It allowed him to move beyond the often superficial or purely imaginative depictions of the Orient that characterized some earlier Orientalist art. Instead, Chataud could observe daily life, the play of light on desert landscapes, the architecture of towns and villages, and the attire and customs of the local population firsthand. This deep engagement with his environment became a hallmark of his artistic practice.

The Algiers School of Orientalism

Marc Alfred Chataud is recognized as one of the co-founders, alongside Joseph Sintès (1829-1913), of what became known as the "École d'Alger" or the Algiers School of Orientalism. Sintès, a Spanish-born painter who also spent much of his career in Algeria, shared Chataud's commitment to depicting Algerian subjects. This school, active roughly from the mid-19th century into the early 20th century, was characterized by a more intimate, realistic, and often less overtly romanticized or sensationalized portrayal of Algerian life compared to some of the grander, more theatrical Orientalist works produced by artists based primarily in Paris.

The artists of the Algiers School, many of whom, like Chataud, lived in Algeria for extended periods, focused on capturing the specificities of the local environment and its inhabitants. Their works often featured everyday scenes, portraits, landscapes, and architectural studies. They aimed for a degree of authenticity in their depictions of clothing, customs, and settings, contributing to a visual ethnography of the region, albeit still filtered through a European colonial lens.

Other notable artists associated with or contributing to the spirit of the Algiers School and the broader depiction of Algerian Orientalism include Étienne Dinet (1861-1929), who later converted to Islam and took the name Nasreddine Dinet, becoming deeply integrated into Algerian life and a passionate advocate for its culture. Gustave Guillaumet (1840-1887) was another highly respected French painter who spent considerable time in Algeria, known for his empathetic and often somber portrayals of desert life. While perhaps not formally part of a rigidly defined "school," artists like Gustave Simonnet and Mohammed Abi Shanab also contributed to the rich visual record of colonial Algeria from an Orientalist perspective. The Algiers School, therefore, represented a significant regional development within the broader Orientalist movement, emphasizing direct observation and a closer connection to the subject matter.

Chataud's Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Marc Alfred Chataud's artistic style is firmly rooted in the academic traditions of the 19th century, yet it is infused with the unique characteristics of his chosen subject matter. His paintings demonstrate a strong command of draftsmanship, a balanced sense of composition, and a keen eye for detail. He worked primarily in oils, employing a technique that allowed for both precise rendering and a subtle evocation of atmosphere.

A key feature of Chataud's style is his sensitive handling of light and color. He masterfully captured the brilliant North African sunlight, its effects on landscapes, architecture, and the human form. His palette, while rich, often avoided the overly garish or exoticized colors sometimes found in Orientalist works, opting instead for tones that conveyed a sense of naturalism and harmony. He was adept at depicting the textures of fabrics, the weathered surfaces of buildings, and the expressive qualities of his human subjects.

Thematically, Chataud's oeuvre explored various facets of Algerian life. He painted bustling souks (marketplaces), tranquil courtyards, the entrances to mosques, and scenes of daily domesticity. His depictions of figures, whether solitary individuals or groups, often convey a sense of quiet dignity. He was interested in portraying the "elegant lifestyle" and the intimate, everyday moments of the people he observed. While his perspective was inevitably that of a European artist in a colonial context, his works often strive for a respectful and observant portrayal, less reliant on the overt exoticism or fantasy that characterized some of his contemporaries.

His landscapes captured the unique beauty of the Algerian terrain, from the arid expanses of the Sahara to the more verdant regions. These works often emphasize the vastness and serenity of the natural environment, sometimes with figures that are small in scale, highlighting the relationship between humanity and the land.

While striving for realism, a touch of the romantic or the picturesque, common to Orientalist art of the period, can also be discerned in his work. The "Orient" was, for many Europeans, a realm of imagination as much as reality, and Chataud's art, while grounded in observation, was not entirely immune to these prevailing artistic currents. However, his long-term residency and intimate approach generally lent his work a greater sense of authenticity and nuanced understanding.

Representative Works

Several works by Marc Alfred Chataud are cited as representative of his style and thematic interests, showcasing his skill in capturing the essence of Algerian life and scenery.

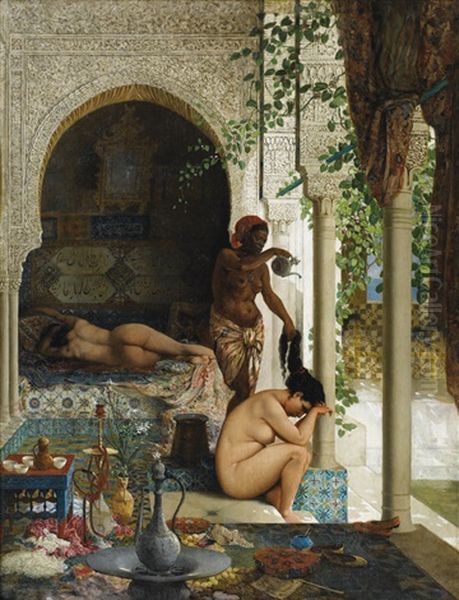

One such painting is "Après le bain" (After the Bath). This title suggests a scene of private, domestic life, a common theme in Orientalist art that often focused on the imagined interiors of harems or bathhouses. Without a specific image readily available for detailed analysis, one can surmise that Chataud would have approached this subject with his characteristic attention to detail, light, and the human form, perhaps depicting figures in a moment of repose, adorned in local attire, within an architecturally detailed setting. Such scenes allowed artists to explore sensuality and the exotic, though Chataud's approach was generally more restrained.

"Café Arabe" (Arab Coffee House) is another indicative title. Coffee houses were important social hubs in North African and Middle Eastern societies, and frequent subjects for Orientalist painters. Chataud's version likely depicted men in conversation, perhaps smoking or drinking coffee, within the characteristic ambiance of such an establishment. These scenes offered opportunities to portray local customs, attire, and social interactions, as well as to explore interior light and shadow. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme also famously depicted such scenes, though Chataud's might have offered a less theatrical, more everyday perspective.

"La Porteuse d'eau" (The Water Carrier) points to a genre scene, a depiction of daily labor. Water carriers were a common sight in many arid regions and became a recurring motif in Orientalist art, symbolizing a timeless, almost biblical way of life. Chataud's portrayal would likely have focused on the dignity of the figure and the physical act of carrying water, set against a backdrop of a street or landscape, perhaps emphasizing the play of sunlight on the figure and their surroundings. Eugène Fromentin, another French Orientalist deeply familiar with Algeria, also depicted scenes of daily life with great sensitivity.

"Femmes dans une rue d'Alger" (Women in an Algiers Street) suggests an outdoor scene capturing the public, yet often veiled, presence of women in Algerian society. Depicting women in public spaces in North Africa was a complex subject for European male artists, often involving observation from a distance or reliance on models. Chataud's work might have focused on the flowing garments, the architectural setting of an Algiers street, and the interactions, however brief, between the figures.

"La cartomancienne au harem" (The Fortune Teller in the Harem) combines two popular Orientalist tropes: the mysterious world of the harem and the theme of fortune-telling or divination. This subject allowed for an element of the exotic and the mystical. Chataud would likely have depicted a richly decorated interior, with female figures gathered around a fortune teller, their expressions and postures conveying curiosity or anticipation. This theme was explored by many Orientalists, including John Frederick Lewis, who was known for his incredibly detailed harem interiors.

These titles, and the works they represent, underscore Chataud's engagement with the typical themes of Orientalist art but also suggest his commitment to observing and rendering the specific details of Algerian life as he experienced it. His works contributed to a visual vocabulary that helped shape European understanding—and misunderstanding—of North African culture.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Legacy

Marc Alfred Chataud achieved a notable degree of recognition during his lifetime. He regularly exhibited his works, a crucial avenue for artists to gain visibility and patronage. Between 1864 and 1868, he participated in the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Salon was the most important venue for an artist to establish their reputation in the 19th century, and Chataud's inclusion indicates the quality and acceptance of his work within the mainstream art world.

His contributions were formally acknowledged on several occasions. He received an honorable mention at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1867, a major international showcase of art and industry. Perhaps most significantly, he was awarded the title of Knight of the Legion of Honour, one of France's highest orders of merit, a testament to his standing as an artist.

Having settled in Algeria, Chataud became an active member of the local art community. He served as the vice-president of the Société des Artistes Algériens et Orientalistes (Society of Algerian and Orientalist Artists), an organization that played a vital role in promoting art in the colony and fostering a sense of artistic identity among those working there. His works were exhibited in Algeria as well as in France, ensuring his visibility in both his native country and his adopted home.

Today, Marc Alfred Chataud's paintings are held in various public and private collections. Notably, the Musée National des Beaux-Arts d'Alger (National Museum of Fine Arts of Algiers) houses works by him, preserving his artistic legacy in the very country that so profoundly inspired him. His paintings also appear in other museums in France and Algeria and occasionally surface in the art market, where they are appreciated by collectors of Orientalist art.

His legacy is intertwined with the broader phenomenon of Orientalism. While contemporary perspectives often critically examine the colonial gaze inherent in much Orientalist art, Chataud's work, particularly due to his long-term residency and focus on everyday life, offers a more nuanced and intimate vision than that of some of his contemporaries. He remains an important figure for understanding the Algiers School and the diverse ways in which French artists engaged with North Africa in the 19th century.

Contemporaries and the Wider Orientalist Milieu

Marc Alfred Chataud operated within a vibrant and extensive network of artists interested in Orientalist themes. His teachers, Emile Loubon and Charles Gleyre, provided his foundational training. Gleyre, in particular, had his own experiences in the East and taught many who would explore diverse artistic paths, including Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, though Chataud's style remained more academic.

In Marseille, he was influenced by painters like Fabius Brest, known for his detailed Ottoman scenes, and Alexandre Jean-Baptiste Brun. His direct collaborator in founding the Algiers School was Joseph Sintès. Other key figures in Algerian Orientalism include Étienne Dinet (Nasreddine Dinet), whose immersion in Algerian culture was profound, and Gustave Guillaumet, celebrated for his poignant depictions of desert life. Gustave Simonnet and Mohammed Abi Shanab were also part of this milieu.

Beyond those directly connected to the Algiers School, the broader Orientalist movement was populated by major figures. Eugène Delacroix is often considered a pioneer of French Orientalism, his 1832 trip to Morocco and Algeria having a seismic impact on his art and inspiring generations. Jean-Léon Gérôme became one of the most famous and commercially successful Orientalists, known for his highly detailed, almost photographic, depictions of scenes from Egypt and the Ottoman Empire, including prayer scenes, slave markets, and bathhouses. Eugène Fromentin, a writer as well as a painter, produced sensitive and atmospheric works based on his travels in Algeria, focusing on landscapes, falconry, and scenes of nomadic life.

Other notable Orientalists include Théodore Chassériau, whose work blended Romanticism with classical influences in his depictions of Algerian subjects. The British artist John Frederick Lewis lived for many years in Cairo and created meticulously detailed watercolors and oils of domestic and street life. American artists also participated, such as Frederick Arthur Bridgman, who studied under Gérôme and painted numerous scenes of Algerian life. Austrian painters like Ludwig Deutsch and Rudolf Ernst were also renowned for their highly polished and detailed Orientalist genre scenes, often painted in their Parisian studios based on photographs and artifacts. Even Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, though he never traveled to the East, painted iconic Orientalist subjects like "La Grande Odalisque," fueling the European imagination.

Chataud's work, therefore, should be seen within this larger context. He shared with these artists a fascination with North Africa and the Middle East, but his approach, shaped by his long-term residency in Algeria, often favored a more grounded, less overtly sensationalized realism.

The Complex Context of Orientalism

It is essential to approach the work of Marc Alfred Chataud and his Orientalist contemporaries with an understanding of the historical and cultural context in which it was created. Orientalism as an artistic and intellectual movement coincided with the peak of European colonialism. French Algeria, the primary subject of Chataud's art, was a settler colony, and the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized was inherently one of unequal power.

Orientalist art, while often aesthetically captivating and demonstrating considerable artistic skill, frequently reflected and reinforced European perceptions of the "Orient." These perceptions could include romanticization, exoticization, and the portrayal of Eastern societies as timeless, sensual, or resistant to progress—stereotypes that sometimes served to justify colonial endeavors. The focus on themes like the harem, slave markets, or scenes of perceived indolence, while appealing to European audiences, could also contribute to a one-dimensional and often inaccurate understanding of complex societies.

However, Orientalism was not monolithic. Artists like Chataud, Dinet, and Guillaumet, who spent significant time living in the regions they depicted, often developed a deeper, more empathetic understanding of the local cultures. Their work could, at times, challenge simpler stereotypes, offering more nuanced and respectful portrayals of individuals and daily life. Chataud's commitment to depicting "intimate and realistic" scenes suggests a desire to look beyond superficial exoticism.

Nevertheless, even the most well-intentioned European artist of the period operated within the framework of colonialism. Their access to certain scenes, their interactions with local populations, and the very act of representing another culture were shaped by this power dynamic. Today, art historians and critics analyze Orientalist art through these complex lenses, appreciating its artistic merits while also acknowledging its historical context and the "colonial gaze" that often informed it.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Algeria

Marc Alfred Chataud dedicated much of his artistic life to capturing the landscapes, people, and culture of Algeria. As a French painter living and working in a colonial setting, he contributed significantly to the Orientalist movement, particularly through his role in co-founding the Algiers School. His work is distinguished by its realistic detail, sensitive portrayal of light and atmosphere, and a focus on the everyday and intimate aspects of Algerian life.

While his name may not be as widely recognized as some of the titans of Orientalism like Delacroix or Gérôme, Chataud's oeuvre provides a valuable and often nuanced perspective on 19th-century Algeria. His paintings, found in museums in France and Algeria, stand as a testament to his artistic skill and his deep engagement with the land and its people. He navigated the complexities of representing a colonized culture, leaving behind a body of work that continues to fascinate and inform, offering a specific and personal vision within the broader, multifaceted story of Orientalist art. His legacy endures as that of an artist who sought to understand and depict a world that was, for many of his European contemporaries, more a realm of fantasy than a lived reality.