Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573–1621) stands as a seminal figure in the history of art, particularly celebrated as one of the earliest and most influential masters of floral still life painting during the Dutch Golden Age. His meticulously detailed and harmoniously composed works not only captured the ephemeral beauty of flowers but also helped establish still life as an independent and respected genre. Born in Antwerp, a vibrant artistic hub, Bosschaert's life and career were shaped by the religious and cultural currents of his time, leading him to create a legacy that would influence generations of artists.

Early Life and Relocation to Middelburg

Ambrosius Bosschaert was born in Antwerp in 1573 into a Protestant family. His father, also named Ambrosius, was a painter, though little is known about his work. The period was one of significant religious turmoil in the Southern Netherlands, then under Spanish Habsburg rule. The Council of Troubles, instituted by the Duke of Alba, led to widespread persecution of Protestants. This oppressive atmosphere prompted many, including the Bosschaert family, to seek refuge elsewhere.

Around 1587, the Bosschaerts relocated to Middelburg, the capital of the province of Zeeland in the newly independent Dutch Republic. Middelburg was a flourishing port city, benefiting from the blockade of Antwerp's Scheldt river and becoming a center for trade, including the burgeoning trade in exotic flowers. This environment, rich with botanical curiosities and a prosperous merchant class eager for art, would prove fertile ground for Bosschaert's burgeoning talent. It was in Middelburg that he would spend the most significant part of his artistic career.

The Middelburg Period: Establishing a New Genre

In Middelburg, Bosschaert established himself as a leading painter. He joined the Guild of Saint Luke, the city's painter's guild, in 1593, a testament to his recognized skill at a relatively young age. He served as dean of the guild on several occasions, indicating his respected position within the artistic community. It was during his Middelburg years that Bosschaert began to specialize in flower paintings, a genre that was then in its nascent stages.

Prior to Bosschaert and his contemporaries, flowers often appeared in art as symbolic elements within larger religious scenes or portraits. Artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder in Antwerp were also pioneering floral arrangements as central subjects around the same time. Bosschaert, however, was among the very first in the Northern Netherlands to dedicate his oeuvre almost exclusively to these intricate depictions of bouquets. His early works from this period already display the hallmarks of his style: symmetrical compositions, bright, clear colors, and an almost scientific precision in rendering each bloom.

The city of Middelburg itself played a role in fostering this specialization. It was home to notable botanical gardens, including one established by the botanist Matthias de l'Obel. Access to rare and exotic flowers, such as tulips recently introduced from the Ottoman Empire, provided artists like Bosschaert with novel and exciting subject matter. These flowers were luxury items, and paintings of them appealed to a wealthy clientele interested in both art and the natural world.

Artistic Style and Meticulous Technique

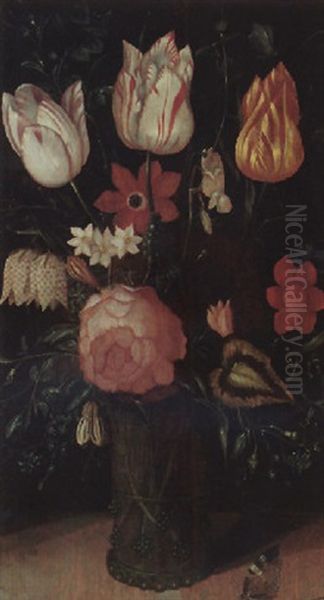

Bosschaert's artistic style is characterized by its meticulous detail, luminous color, and balanced, often symmetrical, compositions. He typically painted on a small scale, frequently using copper panels as his support. Copper provided a smooth, rigid surface that allowed for exceptionally fine brushwork and enhanced the jewel-like quality of his paintings. The smooth surface also contributed to the luminosity of his colors, as light would reflect off the metal through the thin layers of paint.

His bouquets are usually presented frontally, often in ornate vases, niches, or against a plain dark background, which makes the vibrant colors of the flowers stand out. In some later works, he introduced a glimpse of a landscape through a window, adding depth and a sense of space. This feature was also explored by contemporaries like Roelandt Savery, who was active in Utrecht when Bosschaert later moved there.

The flowers themselves are rendered with extraordinary precision. Each petal, leaf, and stem is carefully observed and delineated. Bosschaert often combined flowers that bloomed in different seasons into a single bouquet. This was not an attempt at naturalistic representation of a specific moment but rather a celebration of floral diversity and beauty, a "collection" of perfect specimens. He likely worked from individual studies of flowers, meticulously arranging them into an idealized composition. This practice was common among early flower painters, including Jacques de Gheyn II, another pioneer in the field.

His palette was rich and varied, employing bright reds, yellows, blues, and whites. He achieved a remarkable sense of luminosity through the careful application of thin glazes of oil paint, building up layers to create depth and translucency, particularly in the delicate petals of flowers like tulips and roses. This technique gave his flowers an almost tangible quality, making them appear both lifelike and idealized.

Symbolism and Intellectual Context

While Bosschaert's paintings are undeniably celebrations of natural beauty, they are also imbued with layers of symbolism common in Dutch art of the period. Flowers, with their fleeting beauty, were often associated with the concept of vanitas – the transience of life and the inevitability of death. The presence of insects like butterflies (symbolizing resurrection or the soul), caterpillars, flies, or beetles, and sometimes dewdrops or slightly wilting petals, would have reminded contemporary viewers of these themes.

Shells, another recurring motif in his work and in the broader genre of Dutch still life, were exotic collectibles brought back from distant lands by Dutch traders. Like flowers, they represented both wealth and the wonders of God's creation, but also could carry vanitas connotations, being the beautiful but empty remnants of life. Artists like Balthasar van der Ast, Bosschaert's brother-in-law and pupil, would later specialize in still lifes featuring shells.

The scientific interest of the age also played a role. The 17th century saw a surge in botanical studies and the creation of illustrated botanical encyclopedias. Bosschaert's precise rendering of individual species reflects this burgeoning scientific curiosity. His paintings served not only as decorative objects but also as records of rare and prized botanical specimens, appealing to collectors who were often also avid gardeners or students of natural history. The infamous "Tulip Mania" that would grip the Netherlands in the 1630s was already brewing, and tulips feature prominently in many of Bosschaert's works, reflecting their high value and exotic appeal.

Evolution of His Art

Over his career, Bosschaert's style underwent a subtle evolution. His earlier works, typically from his Middelburg period, often feature densely packed, symmetrical bouquets presented in a relatively shallow space. The lighting is generally even, illuminating each flower clearly. An example is his Still Life of Flowers in a Wan-Li Vase (c. 1609-1610), now in the National Gallery, London, which showcases a vibrant array of blooms in an imported Chinese porcelain vase, a luxury item in itself.

As he matured, particularly after his move from Middelburg, his compositions began to show a greater sense of depth and a slightly more relaxed arrangement of flowers. While symmetry remained important, there was often a greater interplay of light and shadow, creating a more atmospheric effect. The inclusion of open windows with distant landscapes, as seen in works like Vase of Flowers in a Window (c. 1618), added a new dimension to his paintings, linking the interior still life with the wider world. This development can also be seen in the works of other artists moving towards a more naturalistic and atmospheric style in the 1610s and 1620s.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Several key works exemplify Bosschaert's mastery and stylistic traits:

_A Still Life of Flowers in a Wan-Li Vase_ (c. 1609-1610, National Gallery, London): This iconic piece features a rich assortment of flowers, including tulips, roses, irises, and columbines, meticulously arranged in a blue-and-white Chinese Wanli porcelain vase. The precision in rendering both the flowers and the reflective surface of the vase is remarkable. Insects, such as a Red Admiral butterfly and a dragonfly, add to the lifelike quality and symbolic depth.

_Flowers in a Glass Vase_ (1614, National Gallery, London): Here, the bouquet is presented in a simple glass roemer, allowing the stems to be visible through the water. The transparency of the glass and the reflections on its surface are masterfully handled. The flowers, including prominent tulips and roses, are brightly lit against a dark background, emphasizing their vibrant colors.

_Still Life of Colourful Tulips, Roses, and other Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Ledge with a Red Admiral Butterfly and a Fly_ (1606, Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna): An earlier work, this painting already demonstrates Bosschaert's skill in creating a balanced and detailed composition. The variety of flowers, each perfectly rendered, highlights the early interest in botanical diversity.

_Flowers in a Glass Vase_ (1619, National Gallery of Art, Washington): This later work shows a slightly looser, though still highly detailed, arrangement. The bouquet is full and lush, with a strong sense of three-dimensionality. The play of light on the petals and leaves is particularly effective.

These paintings, and others like them, were highly sought after by collectors and commanded high prices even during Bosschaert's lifetime. His consistent quality and appealing subject matter ensured his success.

Influence of and Interaction with Contemporaries

Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder did not work in isolation. He was part of a network of artists who were collectively shaping the new genre of still life. His most significant contemporary in the realm of flower painting was Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625), who worked primarily in Antwerp. While their styles developed somewhat in parallel, there was likely mutual awareness and possibly influence. Both artists shared a love for meticulous detail, vibrant color, and the depiction of rare and exotic flowers. Brueghel often incorporated flowers into larger allegorical or mythological scenes, sometimes in collaboration with artists like Peter Paul Rubens, but he also produced pure flower pieces that rival Bosschaert's in their intricacy.

In Middelburg, Bosschaert would have been aware of other artists exploring still life themes, though he was the preeminent flower painter. The city's artistic community, while smaller than Antwerp's, was active. Later, when Bosschaert moved, he encountered different artistic circles.

Roelandt Savery (1576-1639) was another important contemporary who painted detailed flower pieces, often with a slightly wilder, more naturalistic feel, and frequently included lizards or other small creatures. Savery worked in Prague for Emperor Rudolf II before settling in Utrecht around 1619, overlapping with Bosschaert's time there. Their works share a common interest in botanical accuracy and rich detail.

Jacques de Gheyn II (1565-1629), active in Leiden and The Hague, was another pioneer. His flower paintings, often dated to the first decade of the 17th century, are among the earliest examples of the genre and are characterized by a similar precision and often a starker, more iconic presentation.

Other still life painters of the period, such as Osias Beert the Elder (c. 1580-1623/24) in Antwerp, specialized in fruit and banquet pieces but shared the same commitment to detailed realism and careful composition. Clara Peeters (1594-c.1657), one of the few recognized female artists of the time, also excelled in still life, creating intricate breakfast pieces and fruit arrangements. While their subject matter differed, the underlying aesthetic principles of the early Netherlandish still life tradition were shared. The broader context also includes artists like Floris van Dyck and Nicolaes Gillis, who were pioneers of the ontbijtje (breakfast piece).

The Bosschaert Dynasty: A Family of Painters

Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder was not only a successful painter but also the founder of an artistic dynasty. He trained his three sons, who all became flower painters in their own right, continuing his style and tradition.

Ambrosius Bosschaert the Younger (1609–1645) was the eldest son. He worked in Utrecht and his style closely emulated that of his father, particularly his father's later works. His paintings are characterized by fine detail and often feature similar compositions and flower types.

Johannes Bosschaert (c. 1606/08–1628/29) was the second son. His career was tragically short, but he too produced high-quality flower pieces. His works sometimes show a slightly more dynamic arrangement than his father's earliest paintings.

Abraham Bosschaert (1612/13–1643) was the youngest son. He also painted floral still lifes, often on a small scale, and his work is sometimes confused with that of his brothers or father.

Perhaps the most famous artist associated with Bosschaert's studio was his brother-in-law, Balthasar van der Ast (1593/94–1657). Van der Ast lived with the Bosschaert family after his own father's death and was undoubtedly trained by Ambrosius the Elder. He began by painting flower pieces in a style very close to Bosschaert's but later developed his own distinct manner, becoming particularly renowned for his still lifes featuring shells, fruit, and flowers, often with a more expansive and atmospheric composition than his master's. Van der Ast, in turn, influenced later artists like Jan Davidsz. de Heem.

This family of artists played a crucial role in popularizing and disseminating the genre of floral still life throughout the Dutch Republic. Their collective output ensured that the Bosschaert style remained influential for several decades.

Later Career: Moves to Utrecht and Breda

In 1615 or 1616, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder moved with his family from Middelburg to Utrecht. Utrecht was another important artistic center, home to artists like Abraham Bloemaert and the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Bosschaert joined the Utrecht Guild of Saint Luke in 1616. His reasons for moving are not definitively known but may have been related to seeking new patronage or a more dynamic artistic environment. It was during his Utrecht period that Balthasar van der Ast likely completed his training and began to establish his independent career.

Bosschaert did not stay in Utrecht for long. By 1619, he had moved again, this time to Breda. He continued to paint his signature flower pieces. It was while on a journey to The Hague in 1621, reportedly to deliver a flower painting commissioned by Prince Maurits, that Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder died suddenly. He was only 48 years old but had already produced a significant body of work and established a lasting reputation.

Role as an Art Dealer

Beyond his activities as a painter, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder was also involved in the art trade. This was not uncommon for artists at the time, as it provided an additional source of income and kept them connected to the broader art market. Records indicate that he dealt in paintings by other artists. For instance, there is documentation of him acting as an agent in the sale of works by the Venetian master Paolo Veronese. His experience as a dealer likely gave him a keen understanding of market tastes and may have influenced his own choice of specialization, as flower paintings were becoming increasingly popular and lucrative.

This dual role as artist and dealer highlights the entrepreneurial spirit of many Dutch Golden Age painters, who operated within a burgeoning capitalist economy where art was a commodity as well as an aesthetic pursuit.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder's legacy is profound. He was a true pioneer who played a pivotal role in establishing floral still life as an independent and highly regarded genre in Dutch art. His meticulously crafted paintings, with their brilliant colors, precise details, and harmonious compositions, set a standard for quality and influenced countless artists who followed.

His impact can be seen directly in the work of his sons and his pupil Balthasar van der Ast, who carried the tradition forward. More broadly, he contributed to a visual language that celebrated the beauty of the natural world while often embedding it with deeper symbolic meanings related to transience, wealth, and scientific curiosity. The popularity of flower painting continued throughout the 17th century, evolving with artists like Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Willem van Aelst, and later female artists like Rachel Ruysch, who brought new levels of dynamism and opulence to the genre. However, the foundations laid by Bosschaert and his early contemporaries remained crucial.

His works are prized possessions in major museums around the world, including the National Gallery in London, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Louvre in Paris, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. They continue to be admired for their exquisite craftsmanship and timeless beauty.

Market Reception and Auction History

Even during his lifetime, Bosschaert's paintings were highly valued. The anecdote of his journey to The Hague to deliver a painting for a significant sum to Prince Maurits attests to his elite patronage. A document from 1621 records that he was paid one thousand guilders for a flower piece, a very substantial amount at the time, indicating the high esteem in which his work was held.

In the centuries since his death, Bosschaert's paintings have remained sought after by collectors. His relatively small oeuvre, combined with the exceptional quality of his work, ensures that his paintings command high prices when they appear on the art market.

For example, his Still Life of Colourful Tulips, Roses, and other Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Ledge with a Red Admiral Butterfly and a Fly (1606) was offered at Sotheby's in June 2024 with an estimate of $3 million to $4 million. Another work, Bouquet of Flowers in a Glass Vase (1618), sold for an impressive 5.77 million Swiss Francs at a Koller Auctions sale in Zurich in September 2008. His Tulips and Roses in a Glass Beaker with a Butterfly and a Dragonfly on a Ledge fetched €1,687,500 at a Sotheby's Paris auction in June 2012. These figures underscore the enduring appeal and significant market value of Bosschaert's art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Beauty

Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder was more than just a painter of flowers; he was an innovator who helped define a genre that would become a hallmark of Dutch Golden Age art. His keen observational skills, combined with a masterful technique and an eye for harmonious composition, allowed him to create works of enduring beauty and fascination. His paintings offer a window into a world captivated by the exotic, the scientific, and the symbolic, capturing the delicate splendor of blooms that, though transient in life, achieve immortality on his copper panels. His influence resonated through his family and pupils, and his art continues to enchant viewers and collectors four centuries later, securing his place as a foundational master of still life painting.