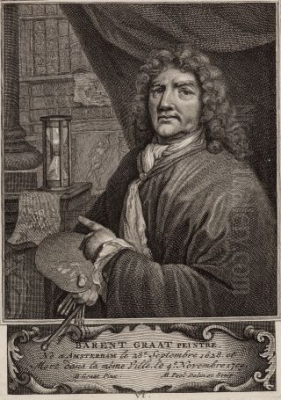

Barend Graat (1628–1709) stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Born in Amsterdam, the bustling heart of a global trade empire and a vibrant artistic center, Graat carved out a multifaceted career as a painter, etcher, and printmaker. His oeuvre spanned historical and mythological scenes, religious altarpieces, idyllic landscapes, and insightful portraits, demonstrating a remarkable adaptability and technical skill that catered to the diverse tastes of his clientele. While perhaps not achieving the towering fame of contemporaries like Rembrandt or Vermeer during his lifetime, Graat's contributions were significant, reflecting both the prevailing artistic currents and his own distinct creative vision.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Barend Graat was baptized in Amsterdam's Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) on September 21, 1628. His artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age, significantly influenced by his uncle, who was reportedly a painter of landscapes and animals. This familial connection likely provided Graat with his initial exposure to the rudiments of art and perhaps instilled in him an early appreciation for the natural world and its depiction, themes that would recur in his later work.

While details of his formal apprenticeship are not extensively documented, it is known that Graat became a keen observer and admirer of the works of Pieter van Laer (1599–c. 1642), an influential Dutch painter who had spent considerable time in Rome. Van Laer, nicknamed "Il Bamboccio" (the ugly doll or puppet) due to his physical appearance, was the progenitor of a style known as "Bamboccianti." These artists specialized in genre scenes depicting the everyday lives of ordinary people – peasants, artisans, and street vendors – often set within Roman or Italianate landscapes. Graat became particularly adept at emulating Van Laer's style, producing numerous works that captured the spirit and subject matter of the Bamboccianti.

Interestingly, despite his proficiency in creating Italianate landscapes, replete with classical ruins and Mediterranean light, there is no definitive evidence that Barend Graat ever traveled to Italy himself. This ability to convincingly evoke foreign climes without firsthand experience speaks to his skill in studying and internalizing the works of other artists, as well as his imaginative capacity. He absorbed the visual language of Italian scenery through prints and paintings available in Amsterdam, a major hub for art trade.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Graat's artistic output was characterized by its diversity. He was not a painter who confined himself to a single genre but rather moved fluidly between historical narratives, religious subjects, portraiture, and landscape painting. This versatility was a hallmark of many successful Dutch artists of the period, who needed to adapt to the varied demands of the burgeoning art market.

In his historical and mythological paintings, Graat demonstrated a solid understanding of classical narratives and an ability to compose complex multi-figure scenes. Works like Minerva and Arachne (c. 1680/1700) showcase his engagement with Ovidian myths, rendered with a clarity and attention to dramatic storytelling that would have appealed to educated patrons. His religious paintings, including altarpieces, catered to both public and private devotion, a significant undertaking in a predominantly Protestant nation where Catholic patronage, though present, was more discreet.

His landscapes, as mentioned, often bore an Italianate stamp, reflecting the enduring popularity of idealized southern European scenery among Dutch collectors. These works typically featured warm light, picturesque ruins, and pastoral figures, creating an atmosphere of tranquil beauty. However, he was also capable of depicting more typically Dutch scenes. His skill in rendering animals, likely honed through his uncle's influence, is evident in many of his pastoral landscapes and genre scenes.

Portraiture formed another significant aspect of Graat's career. He was commissioned to paint individual portraits as well as family groups, a genre that flourished in the prosperous Dutch Republic. These portraits often aimed to convey the status, piety, and familial bonds of the sitters. His approach to portraiture was generally straightforward and realistic, capturing likenesses with competence and often situating his subjects in settings that reflected their social standing or personal interests.

Key Works and Commissions

Several key works help illuminate Barend Graat's artistic contributions and the range of his talents. Among his notable family portraits is The Broers Family (1658). This painting exemplifies the Dutch tradition of group portraiture, aiming to capture not just individual likenesses but also the dynamics and collective identity of the family unit. Such commissions were important markers of social status and familial pride in 17th-century Dutch society.

Another significant work is Company in a Garden (1661), sometimes referred to as Garden Party. This painting depicts a lively outdoor gathering, showcasing Graat's ability to handle multiple figures in a dynamic composition and to convey a sense of social interaction and leisurely enjoyment. The setting, a cultivated garden, was a popular motif, often symbolizing earthly pleasures or, in some contexts, love and courtship. The work demonstrates his skill in rendering textures, from the sheen of fabrics to the lushness of foliage, and in capturing expressive gestures.

His mythological painting Pandora (1676) tackles a well-known classical theme. The painting likely depicts the moment Pandora, the first woman in Greek mythology, opens the jar (or box, in later accounts) given to her by Zeus, releasing all evils into the world, with only Hope remaining inside. Such subjects allowed artists to explore the human form, dramatic narrative, and moral allegory. Graat's rendition would have focused on the classical ideals of beauty and the dramatic tension of the moment, employing a palette and compositional strategies typical of the period's history painting.

The aforementioned Minerva and Arachne (c. 1680/1700) further illustrates his engagement with classical mythology. The story, from Ovid's Metamorphoses, tells of the weaving contest between the goddess Minerva (Athena) and the mortal Arachne, and Arachne's subsequent transformation into a spider. This theme was popular for its dramatic potential and its exploration of hubris and divine power.

A particularly interesting work is the Pastoral Family Portrait (also known as Shepherd Family Portrait). This painting blends portraiture with pastoral and potentially religious symbolism. The depiction of a family in a pastoral setting, possibly with the father figure as a "shepherd," could allude to biblical themes, such as the Good Shepherd, or simply reflect the fashionable taste for arcadian imagery. Such works often carried multiple layers of meaning, appealing to the sitters' desire for both personal representation and an association with virtuous or idyllic ideals.

The Spinoza Portrait: A Matter of Debate

One of the most intriguing and debated aspects of Barend Graat's oeuvre is his association with a portrait believed to depict the renowned philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677). The painting, titled Portrait of a Man before a Sculpture and dated 1666, has been proposed as a likeness of Spinoza, one of the most radical and influential thinkers of the Enlightenment.

The claim gained prominence when Dutch art dealer Constant Vecht presented the work, suggesting that forensic analysis supported its authenticity as a life portrait of the philosopher. If true, it would be an invaluable historical artifact, as contemporary likenesses of Spinoza are exceedingly rare. The painting depicts a man with features considered consistent with other, later, depictions of Spinoza, standing before a sculpture, perhaps alluding to his intellectual pursuits or classical learning.

However, the attribution of the sitter as Spinoza, and even Graat's authorship of this specific portrait, has been subject to scholarly discussion and some skepticism. While Graat was active during Spinoza's lifetime and was a capable portraitist, definitive proof linking this particular image to Spinoza remains elusive for some art historians. The debate highlights the complexities of portrait identification and attribution in art history, where iconographic analysis, provenance research, and stylistic comparison all play crucial roles. Regardless of the ultimate consensus on the sitter's identity, the painting itself is a fine example of 17th-century Dutch portraiture, and its association with Spinoza has brought renewed attention to Graat's work.

Graat as a Teacher and Figure in the Art World

Beyond his own prolific output, Barend Graat also contributed to the artistic landscape as a teacher. He is recorded as having taught Johann Heinrich Roos (1631–1685), a German-born painter who later became highly regarded for his pastoral landscapes and animal paintings, particularly sheep. Roos's style, with its emphasis on animals in idyllic settings, shows a clear affinity with the types of scenes Graat himself sometimes depicted, suggesting a successful transmission of skills and artistic interests from master to pupil.

Graat's standing within the Amsterdam art community is further evidenced by his involvement in art authentication. In 1672, a significant event occurred when art dealer Gerrit Uylenburgh attempted to sell a collection of thirteen paintings to Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, as works by renowned Italian masters. The authenticity of these paintings was questioned, and a panel of experts, including Barend Graat, was convened to assess them. Graat, alongside other prominent artists like Johannes Vermeer (though Vermeer's involvement is more specifically tied to the appraisal of Italian paintings in a separate but related context of disputed sales), Melchior de Hondecoeter, Gerard de Lairesse, and Karel Dujardin, ultimately declared the works to be copies or of inferior quality. This incident underscores Graat's recognized expertise and respected position among his peers, entrusted with a task requiring considerable connoisseurship.

In 1660, Graat married Marritje (Maria) van Oosterwijck, a young widow. This marriage likely provided him with stability and further integrated him into Amsterdam's social fabric. He continued to receive commissions, including for decorative paintings for the homes of affluent Amsterdam families, some of which are reported to have survived in situ, attesting to the quality and durability of his work.

Context: The Dutch Golden Age Art Scene

To fully appreciate Barend Graat's career, it is essential to consider the extraordinary artistic environment of the Dutch Golden Age. The 17th century witnessed an unprecedented flourishing of arts and sciences in the newly independent Dutch Republic. Economic prosperity, fueled by global trade and maritime dominance, created a broad base of patronage beyond the traditional confines of church and aristocracy. Wealthy merchants, burghers, civic organizations, and guilds all became avid consumers of art.

This period saw the rise of specialized genres. While Graat was versatile, many of his contemporaries became famous for mastering specific types of painting. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) was a towering figure, renowned for his deeply psychological portraits, dramatic biblical scenes, and masterful use of chiaroscuro. Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) of Delft created serene and luminous interior scenes, capturing moments of quiet domesticity with unparalleled skill in rendering light and texture. Frans Hals (c. 1582/83–1666) of Haarlem was celebrated for his lively and spontaneous-seeming portraits that captured the vitality of his sitters.

Landscape painting thrived, with artists like Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1628/29–1682) depicting the Dutch countryside with dramatic intensity, and Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709), a student of Ruisdael, known for his more serene woodland scenes and watermills, such as The Avenue at Middelharnis. Marine painting, celebrating Dutch naval power and maritime trade, was another popular genre, with artists like Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633-1707) excelling in this field.

Genre painting, depicting scenes of everyday life, was immensely popular. Jan Steen (c. 1626–1679) was a master of lively, often humorous and moralizing, domestic scenes. Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684) specialized in orderly courtyards and sunlit interiors, often focusing on domestic virtue. Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681) was known for his elegant and refined genre scenes, often depicting members of the upper class, with a remarkable ability to render the texture of satin and other rich fabrics.

The Bamboccianti, including Pieter van Laer, whom Graat admired, represented a specific niche, bringing scenes of Roman street life to a northern audience. Other artists, like Adriaen Brouwer (1605/06-1638), though Flemish, had a significant impact on Dutch genre painting with his depictions of peasant life, often in taverns. Graat's contemporary and sometimes collaborator, Gerard de Lairesse (1641–1711), championed a more classical, academic style, influenced by French art, which gained popularity in the later part of the century.

Barend Graat operated within this vibrant and competitive milieu. His ability to work across multiple genres, from the Italianate landscapes influenced by Van Laer to the family portraits and historical scenes, allowed him to cater to a wider range of patrons. While he may not have reached the singular iconic status of a Rembrandt or Vermeer, he was a respected and productive member of this artistic ecosystem. There is no strong evidence of direct, intense competition or close collaboration with the very top tier like Rembrandt, but he was certainly aware of their work and part of the same artistic conversations happening in Amsterdam. His association with figures like De Lairesse in appraisal contexts shows his integration into the professional art circles.

Later Life and Legacy

Barend Graat continued to paint and etch throughout his long life. He remained in Amsterdam, his native city, where he died on November 4, 1709, at the advanced age of 81. He was buried in the Oude Kerk (Old Church) in Amsterdam. His son, Gysbert Graat, also became a painter, though less is known about his career.

His legacy is that of a skilled and versatile artist who contributed significantly to the Dutch Golden Age. His works are found in various museum collections, including the Amsterdam Museum and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, as well as in private collections. While perhaps not a radical innovator, he was a master of existing forms and styles, adapting them with intelligence and technical proficiency.

Art Historical Reception and Modern Scholarship

The art historical reception of Barend Graat has evolved. For a period, like many competent but not superstar artists of the Golden Age, he might have been somewhat overshadowed by the giants of the era. However, modern scholarship has increasingly sought to understand the full breadth of artistic production, moving beyond a narrow focus on only the most famous names.

Graat's work has been re-evaluated, with scholars noting his skill in composition, his sensitive handling of paint, and his ability to convey narrative and character. His religious paintings have drawn attention, particularly in discussions of Catholic art in the Northern Netherlands, where artists like him provided devotional images for a minority but still significant Catholic population. His role in the Uylenburgh art appraisal highlights his contemporary standing as a connoisseur.

The potential Spinoza portrait has undoubtedly brought his name to a wider public and sparked renewed interest among scholars. This specific painting continues to be a subject of research and debate, involving art historians, philosophers, and forensic specialists. Such discussions help to shed light not only on Graat but also on the practices of portraiture and the intellectual circles of 17th-century Amsterdam.

Modern studies also appreciate his role as a teacher, contributing to the continuation of artistic traditions through students like Johann Heinrich Roos. His decorative works for Amsterdam homes are also recognized as part of the rich material culture of the period, reflecting the desire of affluent citizens to adorn their living spaces with art.

Conclusion

Barend Graat was a highly capable and industrious artist whose career spanned a significant portion of the Dutch Golden Age. From his early emulation of Pieter van Laer's Bamboccianti style to his accomplished history paintings, sensitive portraits, and appealing landscapes, he demonstrated a remarkable range and a consistent level of quality. He successfully navigated the competitive Amsterdam art market, securing commissions, teaching students, and earning the respect of his peers as an expert.

While he may not have achieved the revolutionary impact of some of his contemporaries, Barend Graat remains an important figure for understanding the depth and diversity of 17th-century Dutch art. His paintings offer valuable insights into the tastes, values, and visual culture of one of the most artistically fertile periods in history. His work, from grand mythological scenes to intimate family portraits and the intriguing possibility of the Spinoza likeness, continues to engage and reward study, securing his place as a versatile master of his time.