Karel Dujardin stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of the Dutch Golden Age of painting. Born in Amsterdam and ultimately meeting his end in Venice, Dujardin carved a unique niche for himself, becoming one of the most accomplished and versatile Dutch Italianate painters and etchers of the 17th century. His life journey, spanning from the bustling mercantile heart of Holland to the sun-drenched landscapes of Italy, profoundly shaped his artistic vision, resulting in works celebrated for their delicate execution, atmospheric charm, and keen observation of life, both human and animal.

While precise details of his birth year are sometimes debated, the most commonly accepted date is September 27, 1626, in Amsterdam. He emerged during a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing in the Dutch Republic, an era that produced masters like Rembrandt van Rijn and Johannes Vermeer. Unlike many contemporaries who focused purely on domestic scenes or the specific topography of the Netherlands, Dujardin was drawn to the allure of the South, becoming a key exponent of the Italianate style – Dutch artists who depicted Italian or Italian-inspired landscapes, often bathed in a warm, golden light quite distinct from the cooler illumination typical of northern scenes.

His oeuvre encompasses idyllic pastoral landscapes, lively genre scenes, sensitive portraits, compelling historical and religious subjects, and a remarkable body of etchings. Through these varied works, Dujardin demonstrated not only technical brilliance but also an ability to infuse his subjects with character and a gentle, often tranquil, mood. He successfully blended the Dutch penchant for detailed realism with the idealized beauty and luminous atmosphere associated with the Italian countryside, creating a style that was both distinctly his own and highly appreciated by patrons.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Karel Dujardin was born into a world of commerce and change in Amsterdam. His family background, however, was marked by financial instability; records indicate his parents faced bankruptcy around 1638. This early experience of economic hardship may have contributed to the drive and adaptability evident throughout his career. Details regarding his initial artistic training remain somewhat uncertain, as is common for many artists of this period.

The most persistent tradition, reported by the early art biographer Arnold Houbraken, suggests that Dujardin studied with the prominent Italianate landscape painter Nicolaes Berchem. Berchem himself was a master of depicting sunny, pastoral scenes populated with peasants and animals, and stylistic similarities between the two artists lend credence to this connection. If true, this apprenticeship would have provided Dujardin with a strong foundation in the very style he would come to embrace and refine.

However, the relationship between Dujardin and Berchem is sometimes presented with ambiguity in historical sources. Regardless of the exact nature of their formal relationship – teacher and student, or perhaps colleagues influencing each other – Berchem's style undoubtedly resonated with Dujardin's developing artistic sensibilities. Other potential early influences might include painters like Paulus Potter, renowned for his masterful depictions of animals in Dutch landscapes, whose focus on livestock Dujardin clearly shared, albeit often transplanted to an Italian setting. Some scholars also suggest possible links to Claes Moeyaert, known for his historical and biblical scenes.

What is clear is that Dujardin quickly absorbed the technical skills necessary for a successful career. His early works, likely produced before any extensive travel, already show a promising talent for composition, detail, and the rendering of figures and animals, setting the stage for the mature style that would emerge following his experiences abroad.

The Call of the South: France and the First Italian Journey

Like many Northern European artists of his time, Dujardin felt the magnetic pull of Italy, the cradle of classical antiquity and the Renaissance. Before reaching Italy, however, his journey likely took him through France. Around 1649, he is documented as being in Paris, where he married Suzanne van Royen, reportedly also from the Low Countries (Antwerp). His time in France may have exposed him to different artistic currents, although the Italian influence would ultimately prove more decisive.

An anecdote, again relayed by Houbraken, places Dujardin in Lyon, where he supposedly incurred significant debts. His landlady, seeking repayment, allegedly arranged for him to marry her older niece. While the veracity of such stories is often difficult to confirm, they paint a picture of a young artist navigating the challenges of life abroad. Whether driven by debt, artistic ambition, or a combination thereof, Dujardin eventually made his way to Italy, likely in the early 1650s.

His arrival in Rome marked a pivotal moment in his career. He joined the Schildersbent, the society of mostly Dutch and Flemish artists working in Rome, known informally as the Bentvueghels ("Birds of a Feather"). This group was notorious for its bohemian lifestyle and initiation rituals. Within this fraternity, Dujardin received the bent-name "Barba di Becco" or "Bokbaard," meaning "Goat's Beard," possibly a reference to his appearance or perhaps his skill in depicting goats, which feature prominently in many of his pastoral scenes.

In Rome, Dujardin would have encountered the works of earlier Italianate painters like Pieter van Laer, founder of the Bamboccianti (painters of low-life genre scenes set in Rome), as well as contemporaries like Jan Both and Jan Asselijn. The experience of Italy itself – the quality of the light, the classical ruins, the landscapes of the Campagna, and the rhythm of rural life – had a profound and lasting impact on his art.

Maturing Style: Italianate Landscapes

The time spent in Italy fundamentally transformed Dujardin's artistic vision. His landscapes from this period, and those painted after his return north but clearly inspired by his travels, exemplify the Italianate style. These works typically feature rolling hills, picturesque valleys, ancient ruins often integrated seamlessly into the scene, and clear, warm sunlight that casts soft shadows and illuminates the landscape with a golden hue. This contrasts sharply with the often cooler, more diffused light and flatter terrain depicted by contemporaries focused solely on the Dutch countryside, such as Jacob van Ruisdael or Meindert Hobbema.

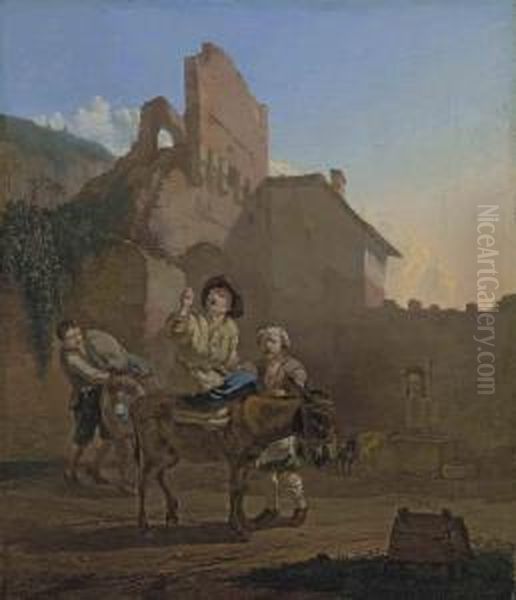

Dujardin populated these idyllic settings with peasants, shepherds, and travellers, often accompanied by their livestock – cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys, and horses. His figures are usually small in scale relative to the expansive landscape, emphasizing the harmony between humanity and nature. Unlike the sometimes rougher scenes of the early Bamboccianti, Dujardin's peasants are often depicted with a degree of grace and dignity, contributing to the overall tranquil and idealized atmosphere of his paintings.

Works like Italian Landscape with Peasants and Animals showcase these characteristics perfectly. The composition is carefully balanced, the light is warm and inviting, and the details of the foliage, the animals' coats, and the textures of stone and earth are rendered with meticulous care. He demonstrated a remarkable ability to capture the specific quality of Mediterranean light, differentiating the time of day and creating a convincing sense of depth and space. He belongs firmly to the second generation of Dutch Italianates, artists who absorbed the lessons of pioneers like Cornelis van Poelenburch and Bartholomeus Breenbergh, and developed a more refined and often more naturalistic approach. His contemporaries in this vein included Nicolaes Berchem, Jan Asselijn, Jan Both, and Adam Pynacker.

Return to the Netherlands: Diversification and Recognition

After his formative years in Italy, Dujardin returned to the Netherlands, settling first perhaps in The Hague, where he became a member of the Confrerie Pictura (the painters' confraternity) in 1656, and later predominantly in Amsterdam. This period, lasting from the mid-1650s until 1675, was highly productive and saw him diversify his artistic output beyond purely Italianate landscapes.

While he continued to paint scenes reminiscent of the Italian countryside, catering to a Dutch market fascinated by the sunny South, he also turned his hand to other genres with considerable success. He undertook portrait commissions, demonstrating a sensitivity and skill comparable to specialized portraitists. His Self-Portrait (c. 1662, Rijksmuseum) shows him confidently presenting himself as a successful artist, while his group portrait, The Governors of the Spinhuis and Nieuwe Werkhuis in Amsterdam (1669, Rijksmuseum), is a significant example of the Dutch 'regentenstuk' (portraits of governors or trustees of charitable institutions). This large-scale work required him to balance individual likenesses with a cohesive group dynamic, a challenge he met admirably.

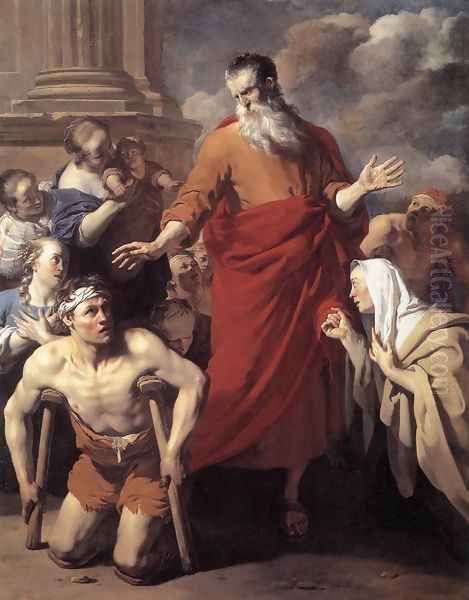

During this Dutch period, Dujardin also created history paintings, often drawing on biblical or mythological themes. A notable example is St. Paul Healing the Cripple at Lystra (1663, Rijksmuseum). This work showcases his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions, convey dramatic narrative, and integrate classical architectural elements, demonstrating a versatility that extended beyond landscape and genre scenes. His handling of light and colour remains assured, adapting to the demands of the subject matter.

He also produced allegorical works, such as the poignant Boy Blowing Bubbles (c. 1663, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen). This painting, depicting a youth engrossed in the fleeting beauty of soap bubbles beside a tomb, is a classic example of a Vanitas theme, reminding the viewer of the transience of life and earthly pleasures. The delicate rendering and contemplative mood are characteristic of Dujardin's refined approach.

Mastery of Genre and Animals

Throughout his career, whether depicting scenes in Italy or the Netherlands, Dujardin displayed a particular affinity for genre subjects and the portrayal of animals. His genre scenes often capture moments of everyday life, particularly rural labour and leisure. Peasants resting, tending their flocks, interacting at markets, or travelling along country roads are recurring motifs. These scenes are rendered with charm and a lack of condescension, often imbued with a gentle humour or quiet dignity.

His painting A Woman and a Boy with Animals at a Ford (c. 1657, National Gallery, London) is a fine example, combining landscape elements with a genre scene. The interaction between the figures and the carefully observed animals – a cow, a sheep, a goat, and a dog – creates a lively yet peaceful composition, bathed in his signature warm light. Another intriguing work is Commedia dell'Arte Show (or Italian Comedians, c. 1657, Louvre), which depicts itinerant performers, possibly quack doctors or charlatans, entertaining a crowd. This work offers a glimpse into popular entertainment of the time and perhaps contains an element of social satire, a theme occasionally explored by Dujardin.

His skill in rendering animals was exceptional and constitutes a major strength of his art. Horses, donkeys, cattle, sheep, and goats are not mere accessories in his landscapes but are depicted with anatomical accuracy and individual character. He captured the texture of their hides, their characteristic postures, and their integration within the environment. This focus aligns him with other Dutch artists celebrated for their animal painting, such as Paulus Potter and Aelbert Cuyp, though Dujardin’s settings are often distinctly Italianate. Philips Wouwerman, another contemporary, was famed for his depiction of horses, often in more dynamic military or hunting scenes, providing a contrast to Dujardin's generally more pastoral approach.

The Art of Etching

Beyond his considerable achievements as a painter, Karel Dujardin was also a highly accomplished etcher. He produced a significant body of around 52 etchings, primarily focusing on the subjects that dominated his paintings: animals, peasants, and idyllic landscapes. These prints demonstrate the same meticulous attention to detail, sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and affection for his subjects found in his painted works.

His etchings are typically small in scale, inviting close inspection. They showcase his mastery of the etching needle, his ability to create fine lines, rich textures, and subtle tonal variations. Works like The Two Pigs (1652), The Mule with a Bell (1653), The Two Sheep and a Goat (1652), and The Sick Goat reveal his profound understanding of animal anatomy and behaviour, captured with remarkable economy and expressiveness. The animals are often the central focus, rendered with sympathy and realism against simple landscape backgrounds.

Dujardin's approach to etching differs from that of his great contemporary, Rembrandt, whose etchings often explored dramatic biblical narratives, intense psychological portraits, and complex light effects on a larger scale. Dujardin's prints are generally more intimate, focusing on the quiet beauty of the rural world. His technique is precise and controlled, emphasizing clarity and delicate detail. He stands alongside artists like Adriaen van Ostade, who also created numerous etchings of peasant life, though Ostade's focus was typically on interior scenes or village festivities rather than Dujardin's sunlit fields. Dujardin's etchings were popular during his lifetime and continued to be admired and collected by connoisseurs for their technical excellence and charming subject matter.

The Final Italian Chapter and Death in Venice

In 1675, after nearly two decades back in the Netherlands, Karel Dujardin embarked on another journey south, seemingly intending to return to Rome. He travelled in the company of his friend and patron, Joan Reynst. Their journey was apparently adventurous; records suggest they travelled via Tangier and possibly Tunis before reaching Italy. This exposure to North Africa, though perhaps brief, might have added another layer to his visual experiences, although its direct impact on his known work is difficult to trace.

He arrived in Rome, where his reputation preceded him, and he was reportedly well-received by the artistic community. He continued to paint, presumably producing works in his established Italianate style, which remained popular. However, his stay in Rome was not destined to be permanent this time.

For reasons that remain unclear, Dujardin travelled onwards to Venice, a city with its own distinct artistic traditions, dominated by colour and light but different in character from Rome or the Dutch school. His time in Venice proved to be tragically short. Karel Dujardin died there on November 20, 1678. According to Houbraken, his death was unexpected, possibly due to food poisoning or a sudden illness. Despite his friend Reynst's earlier attempts to persuade him to return north, Dujardin met his end in the city of canals, far from his native Amsterdam.

Legacy, Collections, and Influence

Karel Dujardin left behind a significant legacy as one of the most refined and versatile Dutch Italianate painters of the 17th century. His ability to synthesize the detailed realism of the Dutch tradition with the idealized landscapes and warm light of Italy resulted in a body of work that continues to charm viewers with its technical skill and gentle beauty. He excelled in multiple genres – landscape, genre scenes, portraiture, history painting, and etching – demonstrating a breadth of talent uncommon even in the diverse Dutch Golden Age.

His influence can be seen in the work of artists who followed him in the Italianate tradition or shared his interest in pastoral themes and animal depiction. Adriaen van de Velde, another highly skilled painter of landscapes and animals, worked in a somewhat similar vein, often depicting scenes with a comparable clarity and delicacy, though typically set in Dutch rather than Italian landscapes. Dujardin's meticulous technique and appealing subject matter ensured his popularity among collectors both during his lifetime and in subsequent centuries.

Today, Karel Dujardin's paintings and etchings are held in the collections of major museums around the world. Significant works can be found in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, the Wallace Collection in London, the British Museum (particularly etchings), the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and numerous other public and private collections across Europe and North America. His works also appear periodically on the art market, attesting to his enduring appeal to collectors of Old Master paintings and prints.

Conclusion: Bridging North and South

Karel Dujardin occupies a unique and important place in the history of Dutch art. He was a master craftsman, skilled in both painting and etching, capable of working across various genres with remarkable finesse. His life journey took him from the heart of the Dutch Golden Age to the sunlit landscapes of Italy, and this experience fundamentally shaped his artistic identity. He became a leading exponent of the Italianate style, capturing the allure of the South for a northern audience while retaining the meticulous observation characteristic of Dutch art.

His legacy lies in his beautiful and tranquil depictions of pastoral life, his sensitive portrayal of animals, his accomplished portraits and history scenes, and his exquisite etchings. Through his art, Karel Dujardin successfully bridged the artistic worlds of Northern and Southern Europe, creating works that celebrate the harmony between humanity and nature, bathed in the warm, evocative light of the Italian sun. His paintings and prints remain a testament to his unique vision and technical brilliance, securing his reputation as a true master of the Dutch Golden Age.