Thomas de Keyser stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of the Dutch Golden Age, a period renowned for its extraordinary artistic and cultural flourishing. Active primarily in Amsterdam during the 17th century, De Keyser distinguished himself not only as a highly sought-after painter, particularly of portraits, but also as a capable architect, continuing a family legacy. His life, spanning roughly from 1596 to 1667, coincided with the rise of the Dutch Republic as a major economic and cultural power, and his work reflects the confidence and prosperity of his time, especially among the burgeoning merchant class and civic elite of Amsterdam.

De Keyser's unique contribution lies in his innovative approach to portraiture and his ability to blend artistic sensitivity with architectural understanding. He navigated the dynamic art market of his day, influencing contemporaries, including the great Rembrandt van Rijn, and leaving behind a body of work that captures the essence of Dutch society in the Golden Age. His legacy is preserved in major museums worldwide, offering a window into the lives and aspirations of the people who shaped one of history's most vibrant artistic periods.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Thomas Hendricksz. de Keyser was born into an artistic family in Amsterdam around 1596. His father was the highly respected and influential architect and sculptor Hendrick de Keyser (1565–1621), a key figure in shaping the architectural landscape of Amsterdam, known for designing prominent buildings like the Zuiderkerk, Westerkerk, and the city's first commodity exchange. Growing up in this environment undoubtedly provided Thomas with early exposure to the principles of design, form, and craftsmanship.

He received comprehensive training, likely initially under his father's guidance, learning not just painting but also sculpture and architecture. Records indicate he trained alongside his brothers, including Pieter de Keyser, who would also become involved in architectural and sculptural work, eventually taking over their father's workshop after his death. Thomas developed skills that extended beyond the fine arts; he became proficient as a stonemason, a trade that connected directly to the architectural side of the family business. This multifaceted training equipped him with a unique perspective, allowing him to integrate architectural elements convincingly into his paintings later in his career.

His early professional life saw him establishing himself within the artistic and commercial fabric of Amsterdam. He was not only an artist but also engaged in business, eventually becoming involved in the trade of building materials like granite, particularly during a period in his middle career. This blend of artistic talent and commercial acumen was not uncommon in the Dutch Golden Age, where artists often needed diverse skills to navigate the competitive market.

The Master of Portraiture

While skilled in multiple disciplines, Thomas de Keyser achieved his most lasting fame as a painter, specifically a portraitist. He became one of Amsterdam's leading portrait painters in the 1620s and 1630s, before the arrival and eventual dominance of Rembrandt. His clientele consisted largely of the city's affluent citizens – merchants, scholars, civic officials, and militia officers – who sought representations that conveyed their status, character, and place in society.

De Keyser's portraits are characterized by their sharp observation, meticulous rendering of details (especially clothing and textures), and insightful characterization. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture a sitter's likeness while also suggesting their personality and social standing. His figures often possess a sense of presence and vitality, engaging the viewer directly or seemingly caught in a moment of quiet contemplation or activity.

His palette tends towards rich, often darker tones, but with skillful use of light to model forms and highlight key features, such as faces and hands, or the sheen of silk and velvet. While perhaps lacking the profound psychological depth or dramatic chiaroscuro that would later define Rembrandt's work, De Keyser's portraits exhibit a clarity, elegance, and refined realism that appealed greatly to his patrons.

Innovation in Portrait Format

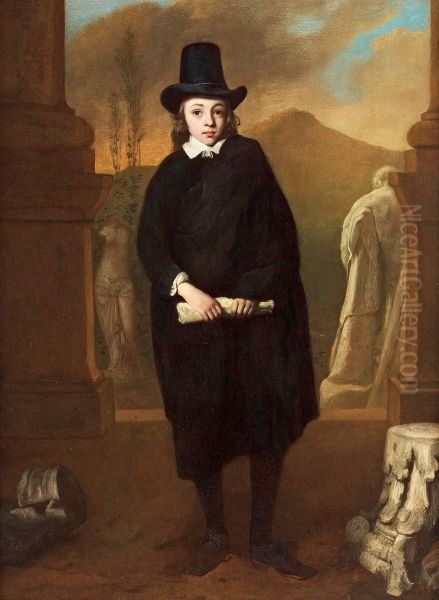

One of Thomas de Keyser's most significant contributions to Dutch art was his popularization of a specific type of portrait: the small-scale, full-length figure set within a defined interior or against a subtle background. Before De Keyser, formal portraiture often favoured larger canvases, particularly for full-length depictions, which were typically reserved for aristocracy or high-ranking officials. Artists like Frans Hals in Haarlem excelled in dynamic, larger-than-life portraits, often half-length or three-quarter length.

De Keyser adapted the full-length format to a more intimate scale, suitable for the domestic interiors of wealthy burghers. These works, often painted on panel, allowed for detailed depictions of the sitter's attire and surroundings, subtly indicating their wealth and taste, without the imposing grandeur of courtly portraiture. This format proved immensely popular and represented a distinctively Dutch adaptation of portrait conventions to suit the values and living spaces of the Republic's elite. His ability to handle figures convincingly within these smaller compositions demonstrated considerable technical skill.

This innovation is considered a key influence on other artists, including the young Rembrandt when he first arrived in Amsterdam from Leiden around 1631. Rembrandt's early Amsterdam portraits show an engagement with the types of compositions and the scale that De Keyser had already successfully established in the city's market.

Civic Guard Portraits: The Cloeck Company

Like many prominent portraitists of the era, Thomas de Keyser received commissions to paint group portraits of Amsterdam's civic militia companies (Schutterij). These paintings were prestigious commissions, destined for display in the companies' headquarters (Doelen), and served as powerful symbols of civic pride, order, and collective identity. His most famous work in this genre is The Company of Captain Allaert Cloeck and Lieutenant Jacobsz. Rotgans, completed in 1632 and now housed in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

This painting exemplifies De Keyser's skill in composing complex group arrangements. He depicts the officers and members of the company with individualized likenesses, capturing a sense of camaraderie and purpose. Unlike the often static arrangements of earlier civic guard portraits, De Keyser introduces a degree of dynamism and interaction, although more restrained than the revolutionary approach Frans Hals was taking in Haarlem around the same time. The figures are arranged across the canvas, some engaging with the viewer, others interacting amongst themselves, creating a lively yet orderly scene.

The meticulous attention to detail in the rendering of uniforms, weapons, and the rich fabrics demonstrates De Keyser's technical prowess. The painting stands as a major example of the genre before Rembrandt's groundbreaking The Night Watch (1642), and alongside works by contemporaries like Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy, who was another dominant force in Amsterdam group portraiture during the 1620s and 30s. De Keyser's work provided a sophisticated model that balanced individual portrayal with group cohesion.

Equestrian Portraits: Status and Skill

Equestrian portraits, depicting sitters on horseback, were traditionally associated with royalty and high nobility, symbolizing power, authority, and martial prowess. In the Dutch Republic, while less common than other portrait types, they were occasionally commissioned by wealthy individuals seeking to project an image of status and refinement. Thomas de Keyser produced notable examples in this genre, again often adapting it to a smaller, more intimate scale than typical European courtly examples.

A well-known example is the Equestrian Portrait of Two Men (c. 1630s), now in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. This work showcases his ability to render horses with accuracy and to integrate the figures and animals harmoniously within a landscape setting. The specific identity of the sitters is uncertain, but the painting conveys an air of confident gentility.

Perhaps his most discussed equestrian work is the Equestrian Portrait of Pieter Schout (c. 1660), housed in the Rijksmuseum. This later work depicts Pieter Schout, a young lawyer from Amsterdam with political ambitions, mounted on a spirited horse performing a "piaffe," a demanding dressage movement where the horse trots in place. This pose highlights Schout's skill as a horseman, an accomplishment associated with aristocratic status. The painting is relatively small, consistent with De Keyser's preference, yet powerfully conveys the sitter's aspirations.

The Pieter Schout portrait has generated considerable art historical discussion. Its creation may be linked to Schout's participation in a ceremonial parade in Amsterdam in 1660. The painting's function extended beyond a simple likeness; it served as a statement of Schout's social standing and cultural refinement. Anecdotes surround the work, including its reproduction as a print by Abraham Blooteling in the 18th century, which helped disseminate the image. Poems by Jan Vos celebrating Schout's achievements further contextualize the portrait's role in constructing his public persona. There was even some debate regarding its attribution, with Adriaen van der Velde, a noted landscape and animal painter, being suggested by some, though the attribution to De Keyser is now generally accepted. Comparisons might also be drawn with the animal paintings of Paulus Potter or the landscapes with horses by Aelbert Cuyp, highlighting the Dutch interest in accurately depicting the natural world alongside human subjects.

Individual Portraits and Character Study

Beyond group and equestrian portraits, De Keyser excelled at individual likenesses. He painted numerous portraits of men and women, often half-length or three-quarter length, but also continuing his characteristic small full-length format. These works demonstrate his consistent ability to capture the textures of fabrics – the deep black of woolen suits, the crisp white of linen ruffs and cuffs, the subtle sheen of silk ribbons – which were important markers of status and wealth.

His sitters are often presented against plain dark backgrounds, focusing attention entirely on the individual. In other cases, subtle architectural elements or furniture might be included to suggest an interior setting. Examples like the Bust of a Woman (on loan to the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel) show his sensitive handling of female portraiture, capturing both the sitter's features and the details of her attire with precision and elegance.

Compared to the psychological intensity found in Rembrandt or the bravura brushwork of Hals, De Keyser's approach is generally more reserved and polished. His figures possess a certain decorum and restraint, reflecting the social norms of the Dutch elite. Yet, within this framework, he achieves convincing and often engaging portrayals. He competed for commissions with other successful Amsterdam portraitists of the time, such as Werner van den Valckert earlier in the century, and later Bartholomeus van der Helst, who became immensely popular for his smooth, highly detailed, and flattering style.

Architectural Activities and Style

Thomas de Keyser's identity as an artist was intrinsically linked to his background in architecture and sculpture, inherited from his father, Hendrick de Keyser. While primarily known today for his paintings, he was active as an architect and involved in the stone trade. After his father's death in 1621, the family workshop continued, likely managed initially by his brother Pieter. Thomas himself was registered in the stonemason's guild.

His most significant architectural involvement came later in his career. From around 1640 to 1652, De Keyser seems to have largely paused his painting activities to focus on commerce, dealing in basalt stone with his brother(s). However, he returned to both painting and architecture. Notably, he was involved in the construction of Amsterdam's magnificent new Town Hall (now the Royal Palace on Dam Square), one of the most ambitious building projects of the Dutch Golden Age.

While the primary design of the Town Hall is credited to Jacob van Campen, a leading proponent of Dutch Classicism, De Keyser played a role in its execution. Sources suggest he contributed to the design aspects and, significantly, served as the city's master stonemason from 1662, overseeing the building work during a crucial phase. His understanding of materials and construction, combined with his artistic eye, would have been invaluable. The Town Hall project also involved other prominent artists, such as the Flemish sculptor Artus Quellinus the Elder, who was responsible for much of the sculptural decoration.

De Keyser's own architectural style, like his father's later work and that of contemporaries like Van Campen, embraced the principles of Dutch Classicism. This style drew inspiration from classical antiquity and Italian Renaissance architects like Palladio, emphasizing symmetry, proportion, harmony, and the use of classical orders (columns, pilasters, pediments). This aesthetic aligned with the Republic's self-image – projecting order, stability, and timeless civic virtue. His paintings often reflect this interest, featuring carefully rendered classical architectural elements in backgrounds or settings.

Mythological and Religious Subjects

While portraiture formed the core of his output, Thomas de Keyser also occasionally painted mythological and historical subjects. This was less common for Dutch artists compared to their counterparts in Italy or Flanders, as the predominantly Calvinist culture of the Northern Netherlands created a different market demand, favouring portraits, genre scenes, landscapes, and still lifes. However, mythological and historical themes were still appreciated, particularly for decorating the homes of the highly educated or for specific allegorical purposes.

Works attributed to him or his circle include scenes like Arcadian Shepherds and depictions of figures like Ariadne. It's worth noting that a painting of Theseus and Ariadne in the Amsterdam Town Hall is sometimes associated with the De Keyser family, potentially being the work of Thomas's son, Hendrick de Keyser II, who also became an artist. These works allowed De Keyser to explore narrative composition and the depiction of the human form in different contexts than portraiture, often drawing on classical aesthetics that resonated with his architectural interests.

Influence and Relationship with Contemporaries

Thomas de Keyser occupied a pivotal position in the Amsterdam art scene of the 1620s and 1630s. His success and stylistic innovations inevitably influenced other artists. His most discussed connection is with Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669). When Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam around 1631, De Keyser was the city's most fashionable portraitist. Rembrandt's early Amsterdam works, particularly his smaller-scale portraits and his use of refined detail, show a clear awareness of De Keyser's popular style. Some scholars suggest Rembrandt consciously adapted elements of De Keyser's approach to appeal to the Amsterdam market before developing his own, more dramatic and psychologically intense style. Over the years, some of De Keyser's works were even mistakenly attributed to Rembrandt, testifying to a perceived similarity in quality or handling, especially in their earlier periods.

There is no definitive record of direct personal collaboration or close friendship between De Keyser and Rembrandt. However, the Amsterdam art world was relatively small, and they certainly knew of each other's work. An indirect link exists through the artist Gerard Dou (1613–1675). Dou is primarily known as Rembrandt's first major pupil in Leiden, famous for his highly detailed 'fijnschilder' (fine painter) style. Interestingly, some sources suggest Dou may have also spent time, possibly earlier, connected to De Keyser's circle or workshop, potentially learning from him before joining Rembrandt. This places Dou as a figure connected to both masters, highlighting the interconnectedness of the artistic community.

De Keyser's work should also be seen in the context of other Dutch Golden Age masters. His precise realism finds parallels in the genre scenes of Gerard ter Borch or the tranquil interiors of Johannes Vermeer, though their subject matter differed. His civic guard portraits invite comparison with those by Frans Hals, Bartholomeus van der Helst, and Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy. His architectural activities connect him to Hendrick de Keyser, Pieter de Keyser, Jacob van Campen, and Artus Quellinus the Elder. His equestrian portraits relate to a tradition explored by artists like Aelbert Cuyp and Paulus Potter, known for their depictions of animals and landscapes. Even the more everyday scenes painted by artists like Jan Steen provide a contrast, highlighting the diverse artistic production of the era.

Later Life, Legacy, and Collections

After his period focusing on the stone trade in the 1640s and early 1650s, Thomas de Keyser returned more actively to his artistic and architectural pursuits. His appointment as city stonemason in 1662 and his work on the Town Hall marked a significant phase in his later career. He continued to paint, including the notable Equestrian Portrait of Pieter Schout around 1660.

Thomas de Keyser died in Amsterdam on June 7, 1667, and was buried in the Zuiderkerk, a church designed by his father. He left behind a significant artistic legacy. His son, Hendrick de Keyser II (sometimes called Hendrick de Keyser the Younger), followed in the family tradition as an artist.

Thomas de Keyser's primary importance lies in his mastery of portraiture during a key period in the Dutch Golden Age. He skillfully catered to the tastes of the Amsterdam elite, capturing their likenesses with precision and elegance. His innovation in popularizing the small-scale full-length portrait format was influential, bridging earlier traditions with the evolving demands of the market and impacting contemporaries like Rembrandt. His dual career as an architect and stonemason further enriched his artistic perspective and contributed directly to the physical fabric of Amsterdam.

Today, his works are held in major international collections. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam holds key pieces, including The Company of Captain Allaert Cloeck and the Equestrian Portrait of Pieter Schout. The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden houses the Equestrian Portrait of Two Men, and the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Kassel holds the Bust of a Woman (on loan). Other paintings can be found in various museums and private collections across Europe and North America, ensuring his contribution to the Dutch Golden Age remains accessible and appreciated. He remains a testament to the versatility and high level of craftsmanship achieved by artists during this remarkable period of Dutch history.