The 17th century in the Netherlands, often referred to as the Dutch Golden Age, was a period of extraordinary artistic efflorescence. Amidst a flourishing economy and a burgeoning middle class with a keen appetite for art, painters specialized in a variety of genres, from portraits and landscapes to scenes of everyday life and, notably, still lifes. Among the skilled practitioners of this last category was Barend van der Meer (1659-1702), an artist whose works, though perhaps not as widely known today as some of his contemporaries, exemplify the refined aesthetics and technical brilliance of Dutch Baroque still life painting. His meticulous attention to detail, sophisticated use of light and shadow, and ability to imbue inanimate objects with a palpable presence mark him as a significant contributor to this cherished tradition.

Early Life and Artistic Milieu

Barend van der Meer was born in Haarlem in 1659, a city that had already established itself as a vibrant center for painting, particularly still life. His father was reportedly an art dealer and a painter himself, specializing in marine scenes characterized by delicate colors and dynamic battle depictions. This familial immersion in the art world would undoubtedly have provided young Barend with early exposure to artistic techniques and the business of art. Growing up in such an environment, surrounded by the works of established Haarlem masters, would have been a formative experience.

Haarlem was home to influential still life painters like Pieter Claesz and Willem Claesz Heda, whose "ontbijtjes" (breakfast pieces) and "banketjes" (banquet pieces) were renowned for their subtle monochrome palettes and masterful rendering of textures. While Van der Meer’s style would evolve, the emphasis on realism and the careful arrangement of objects, hallmarks of the Haarlem school, likely left an impression on him. The city's guilds and artistic circles fostered a competitive yet collaborative environment where artists could learn from one another and push the boundaries of their respective genres.

In 1683, seeking new opportunities or perhaps a different artistic environment, Barend van der Meer relocated to Amsterdam. Amsterdam was, at this time, the bustling commercial and cultural heart of the Dutch Republic, attracting talent from all over Europe. The city offered a larger market for art, with wealthy merchants and patricians eager to adorn their homes with paintings that reflected their status and taste. It was in Amsterdam that Van der Meer would continue to develop his artistic practice, absorbing the influences of the city's leading painters.

The Baroque Sensibility in Van der Meer's Still Lifes

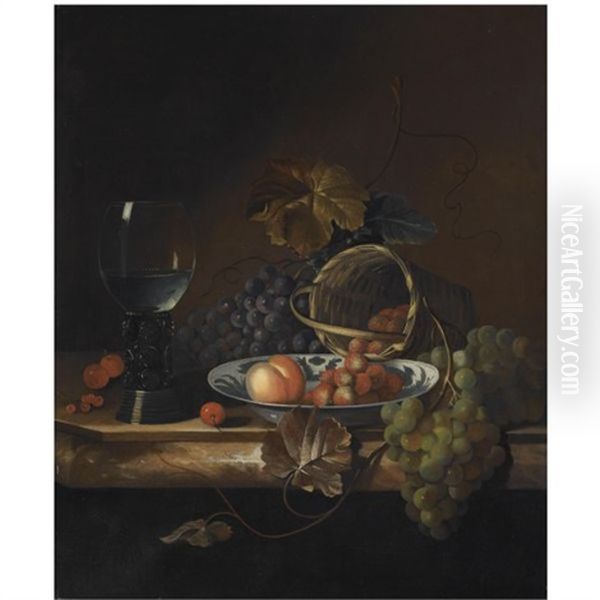

Van der Meer’s artistic output firmly places him within the Baroque style, which, in the context of Dutch still life, translated into a love for rich detail, dramatic lighting, and often opulent subject matter. His paintings are primarily "natura morta," an Italian term meaning "dead nature," which encompasses the depiction of inanimate objects, ranging from fruits and flowers to tableware and hunting trophies.

A key characteristic of Van der Meer's work is his exquisite rendering of detail. Each object in his compositions is delineated with precision, capturing the varied textures of gleaming metal, translucent glass, soft fruit skin, and crisp bread. This meticulousness was a hallmark of Dutch Golden Age painting, reflecting both the artist's skill and a contemporary fascination with the tangible world.

His handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) is particularly noteworthy and aligns with Baroque aesthetics. Light is often used selectively to highlight certain objects, creating a sense of depth and drama. Reflections on glass and metal are rendered with a convincing sparkle, adding to the illusion of reality and the richness of the scene. This skillful manipulation of light not only defines form but also contributes to the overall mood of the painting, which can range from quiet contemplation to sumptuous display.

While his compositions are generally well-balanced, some art historical accounts note that his spatial effects could occasionally appear less sophisticated than those of some of his most illustrious contemporaries, such as Willem Kalf. However, in his finest works, Van der Meer demonstrated a command of composition and an ability to create a harmonious and visually engaging arrangement of diverse elements.

Themes and Symbolism in "Natura Morta"

The subjects of Barend van der Meer’s still lifes are typical of the genre during the Dutch Golden Age. He frequently depicted arrangements of fruits—grapes, peaches, lemons—often accompanied by nuts, bread, and various vessels like wine glasses (roemers), silver platters, and ceramic jugs. These items were not merely decorative; they often carried symbolic meanings, reflecting the cultural and moral preoccupations of the time.

Many Dutch still lifes, including those by Van der Meer, can be interpreted through the lens of "Vanitas." This theme, derived from the biblical Book of Ecclesiastes ("Vanity of vanities, all is vanity"), served as a reminder of the transience of earthly life and the fleeting nature of material possessions and pleasures. Objects like wilting flowers, overripe fruit, snuffed candles, or timepieces could symbolize mortality. Even luxurious items, such as expensive silverware or exotic fruits, could point to the ephemerality of wealth. A peeled lemon, a common motif, with its attractive exterior and sour taste, could symbolize deceptive appearances or the bitterness that can accompany pleasure.

However, not all still lifes were solely focused on Vanitas. They also celebrated the bounty of nature, the prosperity of the Dutch Republic, and the pleasures of domestic life. The meticulous depiction of everyday objects elevated them, inviting viewers to appreciate the beauty in the ordinary. Van der Meer’s works, with their careful arrangements and rich textures, would have appealed to patrons who appreciated both the skillful artistry and the potential layers of meaning.

Representative Works and Their Characteristics

Several works by Barend van der Meer survive, offering insight into his artistic capabilities. One of his representative pieces is "Still Life with Goblet," painted in 1686 and now housed in a museum collection. While specific visual details of this particular painting are not extensively documented in readily available general sources, one can infer from his broader oeuvre that it would likely feature a carefully arranged assortment of objects, with the goblet serving as a focal point, its transparency and reflective qualities expertly rendered. Such a work would showcase his ability to capture different materials and his characteristic use of light.

His "Natura morte" paintings, some of which are held in the prestigious collection of the Musée du Louvre in Paris, are central to his legacy. These works typically display a variety of foodstuffs and tableware, arranged on a draped table. The compositions often create a sense of abundance, with fruits spilling from bowls or platters, and light glinting off polished surfaces. The Louvre's examples would demonstrate his adherence to the high standards of realism and craftsmanship prevalent in Dutch still life.

Another notable painting is "Stillleben mit Kakadu" (Still Life with Cockatoo), located in the Kunsthistorisches Museum (KHM), Gemäldegalerie, in Vienna. The inclusion of an exotic bird like a cockatoo adds a touch of the unusual and the luxurious, as such creatures were expensive imports and symbols of wealth and global trade. This painting would highlight Van der Meer's ability to integrate living creatures into his still life arrangements, a practice also seen in the works of artists like Jan Weenix or Melchior d'Hondecoeter, though they specialized more in game pieces and bird paintings respectively.

The painting "Finely Laid Table with a Moor," dated between 1675-1680 and housed in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, is a particularly interesting work. The inclusion of a human figure, specifically a Moorish servant, in a still life composition was a motif used by several artists, including Willem Kalf. Such paintings, often termed "pronkstilleven" (sumptuous or ostentatious still lifes), showcased an array of luxury items – silver, porcelain, rich textiles, and exotic fruits – and the presence of a servant, often of African or Asian descent, further emphasized the wealth and cosmopolitan connections of the owner. This work demonstrates Van der Meer's engagement with the more elaborate and opulent end of the still life spectrum.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Barend van der Meer worked during a period rich with exceptional still life painters, and his art should be understood within this vibrant context. His style shows an awareness of, and in some cases a direct influence from, several key figures.

The most frequently cited influence is Willem Kalf (1619-1693), one of the most celebrated still life painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Kalf was renowned for his "pronkstilleven," characterized by their opulent displays of silverware, Chinese porcelain, Turkish carpets, and luminous fruits like oranges and lemons, often set against dark, atmospheric backgrounds. Van der Meer’s attempts at similar luxurious arrangements and his handling of light on reflective surfaces show an affinity with Kalf’s work. While art historians have sometimes noted Van der Meer's spatial arrangements as occasionally less masterful than Kalf's, his best pieces certainly approach the richness and textural brilliance of the older master.

Other important contemporaries whose work provides context for Van der Meer include:

Willem Claesz Heda (1594-1680) and Pieter Claesz (1597-1660): These Haarlem masters were pioneers of the "monochrome banketje." Their compositions, though often less colorful than later Baroque still lifes, are marvels of subtle tonal gradation and textural rendering, depicting pewter, glass, and simple foodstuffs with incredible realism. Van der Meer, having started in Haarlem, would have been familiar with their influential style.

Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684): Active in both Utrecht and Antwerp, De Heem was a master of lavish floral still lifes and fruit pieces, often characterized by vibrant colors, complex compositions, and a profusion of objects. His work represents a more exuberant and decorative strand of Baroque still life, and his influence was widespread.

Abraham van Beyeren (1620/21-1690): Known for his sumptuous banquet pieces laden with silverware, fruit, and seafood, as well as his dramatic fish still lifes. Van Beyeren’s rich textures and dynamic compositions were highly regarded.

Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750): A slightly younger contemporary, Ruysch became one of the most successful flower painters of her time. Her delicate and scientifically accurate depictions of flowers, often arranged in dynamic, asymmetrical bouquets, represent the peak of this subgenre.

Adriaen van Utrecht (1599-1652): A Flemish painter whose elaborate market and kitchen scenes, as well as pronkstilleven, often featured a profusion of game, fruit, and vegetables, influencing painters in both the Southern and Northern Netherlands.

Frans Snyders (1579-1657): Another influential Flemish artist, Snyders was known for his large-scale market scenes and hunting still lifes, often filled with animals and an abundance of produce. His dynamic and energetic style had a significant impact on the development of Baroque still life.

Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573-1621): An earlier pioneer of flower painting, whose meticulously detailed and symmetrically arranged bouquets laid the groundwork for later developments in floral still life.

Clara Peeters (1594-c.1657): One of the few prominent female painters of the early Dutch Golden Age, Peeters was an innovator in still life, known for her detailed breakfast pieces and arrangements featuring valuable objects.

The artistic environment of Amsterdam, where Van der Meer spent a significant part of his career, was also home to giants like Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and, for a time, Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), though their primary genres differed. The overall emphasis on realism, the skillful use of light, and the desire to capture the material world were pervasive across Dutch art of this period.

Artistic Legacy and Collections

Barend van der Meer’s contribution to Dutch Golden Age still life lies in his consistent production of high-quality paintings that embody the key characteristics of the genre: meticulous realism, sophisticated handling of light and texture, and an ability to create visually engaging compositions. While he may not have achieved the revolutionary status of a Kalf or a Rembrandt, his work is a testament to the high level of skill and artistic sensibility prevalent among Dutch painters of his era.

His paintings served the demands of a discerning clientele who appreciated the beauty of everyday objects rendered with extraordinary skill. These works adorned the homes of prosperous citizens, reflecting their owners' taste, wealth, and, at times, their moral and philosophical outlook through embedded symbolism.

Today, Barend van der Meer's works are found in several important European museum collections, ensuring their preservation and accessibility for study and appreciation. As mentioned, the Musée du Louvre in Paris holds examples of his "Natura morte." The Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna preserves his "Stillleben mit Kakadu," and the Alte Pinakothek in Munich houses the "Finely Laid Table with a Moor." The presence of his works in such esteemed institutions underscores their art historical significance. Beyond these public collections, other paintings by Van der Meer likely reside in private collections and occasionally appear in the art market, attesting to a continued, if specialized, interest in his oeuvre.

The study of artists like Barend van der Meer is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the Dutch Golden Age. While a few names often dominate popular perception, the richness and depth of this artistic period are built upon the contributions of many talented individuals who specialized, innovated, and excelled within their chosen genres. Van der Meer, with his luminous and detailed still lifes, remains a fine representative of this remarkable chapter in art history. His ability to transform humble arrangements of fruit, glass, and metal into captivating images speaks to the enduring power of still life painting and the particular genius of the Dutch masters.

Conclusion

Barend van der Meer navigated the competitive art world of 17th-century Netherlands with considerable skill, producing still life paintings that capture the opulence and contemplative spirit of the Baroque era. From his beginnings in Haarlem to his mature period in Amsterdam, he absorbed and reinterpreted the prevailing artistic trends, creating works characterized by their meticulous detail, masterful play of light, and rich textural qualities. Influenced by masters like Willem Kalf, yet developing his own distinct touch, Van der Meer contributed to the enduring legacy of Dutch still life painting. His works, found in major European museums, continue to offer viewers a glimpse into the aesthetic values and material culture of the Dutch Golden Age, celebrating the beauty of the everyday and the transient nature of earthly pleasures through the enduring medium of paint. He remains an important figure for those who appreciate the subtle artistry and profound depth that can be found in the quiet world of still life.