Willem Kalf (1619-1693) stands as one of the most distinguished and influential still life painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Renowned primarily for his opulent and meticulously rendered pronkstilleven, or sumptuous still lifes, Kalf captured the essence of Dutch prosperity and its engagement with a wider world during the 17th century. His works are celebrated for their sophisticated compositions, masterful handling of light and shadow, and extraordinary ability to depict the textures of luxurious objects, from gleaming metalwork to fragile Chinese porcelain. Kalf's art not only reflects the aesthetic tastes of his affluent patrons but also offers insights into the complex interplay of wealth, global trade, and symbolic meaning in his time.

Early Life and Formation in Rotterdam and Paris

Willem Kalf was born in Rotterdam in 1619, baptised on November 3rd. He hailed from a prosperous background; his father, Jan Jansz. Kalf, was a wealthy cloth merchant who also held municipal positions, including serving as a member of the Rotterdam council. This comfortable upbringing likely provided Kalf with a solid education and exposure to the finer things in life, elements that would later feature prominently in his art. Although details about his earliest artistic training are scarce, it is believed he may have initially studied under Hendrick Pot (c. 1580-1657), a painter known for portraits and genre scenes, or perhaps Cornelis Saftleven (1607-1681), another Rotterdam artist whose work included landscapes and genre paintings, sometimes featuring barn interiors that bear some resemblance to Kalf's earliest works.

Around the late 1630s, likely towards 1640 or 1641, Kalf moved to Paris. This period was crucial for his artistic development. He settled near Saint-Germain-des-Prés, an area known for its community of Flemish and Dutch artists. During his time in Paris, which lasted until about 1646, Kalf primarily focused on painting rustic interiors and simple still lifes. These early works often depicted humble kitchen or barn settings, featuring arrangements of vegetables, copper pots, pans, buckets, and other everyday objects. Figures, when included, are typically small and relegated to the background, suggesting Kalf's primary interest lay in the inanimate objects themselves.

The Parisian artistic environment exposed Kalf to various influences. He interacted with Flemish émigré artists, and his early style shows an affinity with the work of painters like David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690), known for his peasant scenes and detailed interiors. Kalf's compositions from this period are characterized by their relatively simple arrangements, often set against dark, shadowy backgrounds, which allowed him to experiment with the effects of light on different surfaces. It was also during his Paris years that Kalf began to refine his technique, developing the sensitivity to texture and light that would become hallmarks of his mature style. His work from this time may have also caught the attention of, or perhaps even influenced, French painters like the Le Nain brothers (Antoine, Louis, and Mathieu), who were also exploring genre scenes with a focus on realism and dignity.

Return to the Netherlands: Amsterdam and the Rise of Pronkstilleven

After his formative years in Paris, Willem Kalf returned to the Netherlands. He is documented in Rotterdam briefly in 1646, but by 1651 he had married Cornelia Pluvier van Vollenhoven in Hoorn. Cornelia came from a notable family; her father was a clergyman, and she was related through her mother to the poet and playwright Joost van den Vondel, who would later praise Kalf's work. Following his marriage, Kalf settled in Amsterdam around 1653, the vibrant commercial and artistic heart of the Dutch Republic. It was here that his career truly flourished, and he established himself as a leading master of still life painting.

In Amsterdam, Kalf shifted his focus dramatically from the rustic simplicity of his Paris works to the creation of elaborate and luxurious still lifes known as pronkstilleven. This genre, which translates to 'ostentatious' or 'sumptuous' still life, aimed to display wealth, sophistication, and often, exoticism. Kalf became arguably the most refined practitioner of this style. His compositions grew more complex, featuring carefully arranged assortments of expensive objects that appealed to the wealthy merchant class of Amsterdam, who were eager patrons of art that reflected their status and global connections.

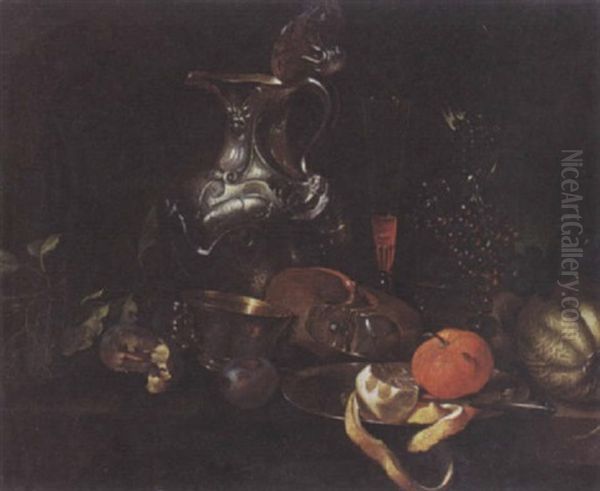

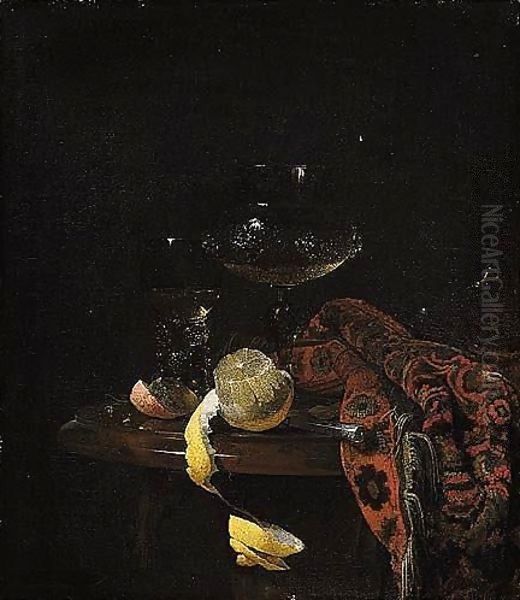

These mature works typically showcase items like intricate silver and gold vessels, imported Chinese porcelain bowls often filled with fruit like lemons and oranges, delicate Venetian glassware, Turkish carpets or rich damask tablecloths used as backdrops, and sometimes exotic elements like nautilus shells mounted in ornate metalwork or even lobsters. Kalf arranged these objects with an unerring sense of balance and harmony, often using a pyramidal structure to organize the composition. His mastery lay not just in the selection of objects but in his unparalleled ability to render their diverse textures and capture the play of light upon their surfaces, creating scenes of breathtaking realism and opulence. He also became involved in the art trade, acting as an expert and dealer, further cementing his position within Amsterdam's thriving art market.

The Art of Pronkstilleven: Luxury, Trade, and Symbolism

The pronkstilleven genre, perfected by Willem Kalf in Amsterdam, was more than just a display of beautiful objects; it was deeply embedded in the cultural and economic context of the Dutch Golden Age. The Dutch Republic, particularly Amsterdam, was a global hub of trade and finance. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) brought vast wealth and exotic goods from Asia, while trade networks extended across Europe and the Mediterranean. Kalf's paintings directly reflect this global reach and the resulting prosperity.

The objects Kalf chose to depict were often status symbols. Chinese blue-and-white porcelain, known as kraakporselein, was highly prized and imported in large quantities, signifying the owner's connection to international trade and their refined taste. Elaborately crafted silver-gilt cups, ewers, and trays demonstrated inherited wealth or recent success. Venetian glass, famed for its delicacy, spoke of sophisticated European connections. Richly patterned Turkish carpets, often used as tablecloths rather than floor coverings in paintings, added a touch of exotic luxury and vibrant color. Even the fruits depicted, such as lemons and oranges, were imported and relatively expensive, adding to the overall sense of abundance.

Beyond the display of wealth, Kalf's still lifes often carried subtle symbolic meanings, characteristic of much Dutch art of the period. The concept of vanitas – the reminder of life's transience and the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures – is frequently woven into these luxurious arrangements. A peeled lemon, with its tartness and short lifespan once exposed, could symbolize the bitterness beneath superficial beauty or the passage of time. A watch, occasionally included, served as a direct reminder of mortality. Even the most perfect-looking fruit might show a subtle blemish, hinting at decay. The juxtaposition of enduring materials like gold and porcelain with perishable items like fruit and flowers created a tension between worldly wealth and spiritual concerns, prompting viewers to reflect on deeper values amidst the visual splendor. Kalf masterfully balanced the celebration of material beauty with these underlying moral or philosophical undertones.

Mastery of Light, Color, and Texture

Willem Kalf's enduring fame rests significantly on his extraordinary technical skill, particularly his handling of light, color, and texture. He possessed an almost unparalleled ability to differentiate between the surfaces of various materials and to depict how light interacted with each one. His paintings are often characterized by a dramatic use of chiaroscuro, with objects emerging luminously from deeply shadowed backgrounds, a technique reminiscent of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), though applied to a different genre.

Kalf used light not just for illumination but to define form, create atmosphere, and guide the viewer's eye. Highlights gleam brilliantly on the polished surfaces of silver and gold, catch the delicate transparency of glass, and softly illuminate the smooth glaze of porcelain. He was particularly adept at capturing reflected light, showing how colors and shapes subtly mirrored onto adjacent objects, adding a layer of complexity and realism to the scene. The way light filters through a glass of wine, reflects off the intricate chasing on a silver platter, or models the bumpy skin of an orange demonstrates his keen observation and meticulous execution.

His color palette, while often dominated by the rich tones of the objects themselves set against dark backgrounds, was sophisticated and harmonious. He used color to create focal points and to enhance the sense of luxury. The vibrant blues of Chinese porcelain, the warm golds of metalwork, the deep reds of wine or carpets, and the bright yellows and oranges of citrus fruits are rendered with intensity and nuance. Kalf understood how colors interacted, using complementary tones to make objects stand out and analogous colors to create harmony within the composition.

Furthermore, Kalf's rendering of texture was exceptional. The viewer can almost feel the coolness of metal, the smoothness of glass, the delicate fuzz of a peach, the rough peel of a lemon, or the intricate weave of a carpet. This tactile quality adds immensely to the realism and sensory appeal of his paintings, inviting the viewer to appreciate not just the visual appearance but the imagined physical presence of the objects depicted. This combination of light, color, and texture mastery elevates Kalf's work beyond mere representation to a profound exploration of visual perception and material beauty.

Key Works and Analysis

Several key works exemplify Willem Kalf's mature style and artistic concerns. His Still Life with Drinking Horn of the St. Sebastian Archers' Guild, Lobster, and Glasses (c. 1653, National Gallery, London) is an early example of his Amsterdam period pronkstilleven. It features the ceremonial drinking horn of a civic guard company, linking the display of luxury to civic pride. The inclusion of a bright red lobster adds a dramatic splash of color and exoticism, while the various glasses showcase his skill in rendering transparency and reflection. The composition is complex yet balanced, set against his characteristic dark background.

Perhaps his most famous works involve Chinese porcelain and nautilus cups. Still Life with a Chinese Porcelain Jar (c. 1669, Indianapolis Museum of Art) highlights a Wanli-period porcelain jar, demonstrating the importance of these imported goods. The arrangement includes fruit, glassware, and a draped carpet, all rendered with exquisite detail and sensitivity to light.

Still Life with Chinese Bowl, Nautilus Cup, and Other Objects (1662, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid) is considered one of the pinnacles of his achievement and a masterpiece of Western still life painting. It features a blue-and-white porcelain bowl filled with oranges and a lemon, alongside an elaborately mounted nautilus shell cup, Venetian-style glassware, and a pocket watch. The composition is a marvel of balance, with objects carefully placed on a marble tabletop partially covered by a rich oriental rug. The interplay of light on the varied surfaces – the gleaming porcelain, the iridescent nautilus shell, the reflective glass, the soft fruit, and the textured rug – is breathtaking. The watch subtly introduces the vanitas theme amidst the opulence.

Another significant work is Still Life with an Aquamanile, Fruit, and a Nautilus Cup (1660, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.). This painting again features luxury items, including an aquamanile (a ceremonial ewer, often in animal form, though here more classical), fruit, and the recurring motif of the nautilus cup. The arrangement is dense and rich, showcasing Kalf's ability to handle complex compositions and render diverse textures under dramatic lighting. These works, among others held in major collections like the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (e.g., Still Life with Ewer, Vessels, and Pomegranate, c. 1643-44, showing an earlier phase, and Still Life with Silver Ewer, c. 1655-60) and the Getty Center, solidify Kalf's reputation as a master of the genre.

Contemporaries, Influence, and Reputation

Willem Kalf operated within a rich artistic landscape and interacted with, or was influenced by, several key figures. His early work shows debts to Rotterdam artists like Cornelis Saftleven and possibly Hendrick Pot. His mature pronkstilleven style, while highly original, built upon the foundations laid by earlier Haarlem still life painters like Pieter Claesz. (c. 1597-1660) and Willem Claesz. Heda (1594-1680), who specialized in more restrained, monochromatic banquet pieces (banketjes). Kalf took their focus on texture and light but infused it with greater color, complexity, and luxury.

Kalf's own influence was significant. His sophisticated pronkstilleven set a standard for other Dutch still life painters, including Abraham van Beyeren (1620/21-1690) and Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1683/84), although their styles differed in detail and emphasis. His student, Jurriaen van Streek (1632-1687), closely followed his master's style, producing similar luxurious still lifes. As mentioned, Kalf's work during his Paris stay may have impacted French genre painters like the Le Nain brothers.

Kalf enjoyed considerable recognition during his lifetime. He was praised by the influential poet Joost van den Vondel. The painter and theorist Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711), known for his classicizing tastes, held Kalf in high regard, mentioning him favorably in his influential book Groot Schilderboek (Great Book of Painting), indicating a close relationship and mutual respect between the two artists. However, not all later assessments were purely laudatory. The biographer Arnold Houbraken, writing in the early 18th century, acknowledged Kalf's skill but perhaps found his focus on luxurious display somewhat superficial compared to history painting, which was considered the highest genre. Nevertheless, Kalf's reputation as a supreme master of still life has endured and grown over time.

His dual role as a painter and an art dealer/appraiser also placed him at the center of the Amsterdam art world. This expertise likely sharpened his eye for quality objects, both to include in his paintings and to trade. His connoisseurship was evidently respected, adding another layer to his professional standing beyond his artistic output.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

In his later years, Willem Kalf seems to have painted less, possibly focusing more on his activities as an art dealer and expert. His last known dated painting is from 1679/80. Despite this apparent decrease in production, his reputation remained high. He continued to live and work in Amsterdam, a respected figure in the city's cultural life.

His life came to an unexpected end on July 31, 1693. According to Arnold Houbraken, Kalf was returning home late after visiting a friend and discussing art. While walking near the Bantammerstraat bridge, he stumbled and fell. Although he managed to get home, he died later that night from his injuries. His death prompted a eulogy from the poet E. van den Hove, who praised Kalf as someone who truly "understood painting," a testament to the esteem in which he was held by his contemporaries.

Willem Kalf's legacy is profound. He is universally recognized as one of the greatest still life painters of the Dutch Golden Age, and arguably of all time. He elevated the pronkstilleven genre to its highest level of refinement and sophistication. His works are admired not only for their stunning visual beauty and technical brilliance but also as invaluable documents of 17th-century Dutch culture, reflecting its prosperity, global trade connections, and complex attitudes towards wealth and mortality.

His paintings continue to captivate audiences in major museums around the world, including the Rijksmuseum, the Louvre, the National Gallery in London, the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. His mastery of light, his ability to render texture, and his sophisticated compositions remain benchmarks against which other still life paintings are often measured. Willem Kalf's luminous world, filled with carefully arranged treasures emerging from evocative shadows, offers a timeless glimpse into the splendor and subtleties of the Dutch Golden Age.