An Introduction to the Master

Bartholomeus van der Helst stands as one of the most accomplished and sought-after portrait painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Born around 1613 in Haarlem, Netherlands, into the family of an innkeeper, he rose to become the favoured artist of Amsterdam's elite during the mid-17th century. His life spanned a period of extraordinary cultural and economic flourishing in the Dutch Republic, an era he captured with remarkable skill and elegance. Van der Helst passed away in Amsterdam on December 16, 1670, leaving behind a legacy of works that epitomize the confidence and prosperity of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Van der Helst's journey began in Haarlem, a significant artistic centre in its own right. However, his professional life would unfold primarily in Amsterdam, the bustling heart of the Dutch Republic. While details of his earliest training are not definitively documented, art historians suggest he likely received instruction from Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy, a prominent Amsterdam portraitist. This connection is inferred from stylistic similarities in their work.

Furthermore, Van der Helst's developing style shows an awareness of the broader artistic currents of the time. Influences from the dynamic brushwork of Frans Hals, another Haarlem native, and the rich, vibrant palette and compositional grandeur associated with the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens can be discerned in his paintings. He skillfully synthesized these influences into a unique approach that would soon captivate Amsterdam's discerning clientele.

Ascendancy in Amsterdam

A pivotal moment in Van der Helst's personal and professional life occurred in 1636 when he married Anna du Pire. Anna hailed from a prosperous merchant family in The Hague, and this union significantly enhanced Van der Helst's social standing and provided a degree of financial stability. This connection likely opened doors within Amsterdam's influential circles, complementing his burgeoning artistic talent.

His career in Amsterdam took off rapidly. By 1639, a relatively early point in his career, he received a prestigious commission to paint a large group portrait for the Amsterdam Arquebusiers' civic guard (the Kloveniersdoelen). Receiving such a significant commission demonstrated his quick ascent and the high regard in which his skills were already held. This early success laid the foundation for a career defined by important civic and private commissions.

Artistic Style and Characteristics

Van der Helst developed a distinctive style perfectly attuned to the tastes of his affluent patrons. His portraits are characterized by their elegance, meticulous attention to detail, and a smooth, refined finish. He excelled at capturing the textures of luxurious fabrics – silks, velvets, and lace – rendering them with convincing realism. His depictions of sitters often possess a confident, assured presence, sometimes subtly idealized or flattered, which undoubtedly contributed to his popularity.

While some early works, like the 1637 Regents of the Walloon Orphanage, show a clear engagement with the dramatic light and psychological depth associated with his contemporary, Rembrandt van Rijn, Van der Helst's style evolved. He moved towards a brighter palette, clearer lighting, and a more polished, decorative aesthetic. This shift distinguished him from Rembrandt and aligned perfectly with the preferences of Amsterdam's wealthy burghers who desired portraits reflecting their status and sophistication. His style was often described as possessing great clarity and plasticity.

He demonstrated versatility in his subject matter, painting individuals from various strata of society, including nobles, wealthy merchants, military officers, civic officials, and even more humble figures like shepherdesses, though his fame rests primarily on his portraits of the elite.

Masterpieces and Major Works

Van der Helst's reputation is anchored by several key masterpieces, particularly his large-scale group portraits. Foremost among these is the monumental Banquet of the Amsterdam Civic Guard in Celebration of the Peace of Münster, completed in 1648. This vibrant painting commemorates the treaty that ended the Eighty Years' War with Spain and formally recognized Dutch independence. It depicts members of the St. George Civic Guard (St. Jorisdoelen) feasting together. The work is celebrated for its lively composition, the individualised portrayal of numerous figures, and its brilliant rendering of details, from the glassware to the guards' attire. Contemporaries lauded it, and some even considered it superior to Rembrandt's Night Watch in its clarity and successful depiction of numerous distinct individuals.

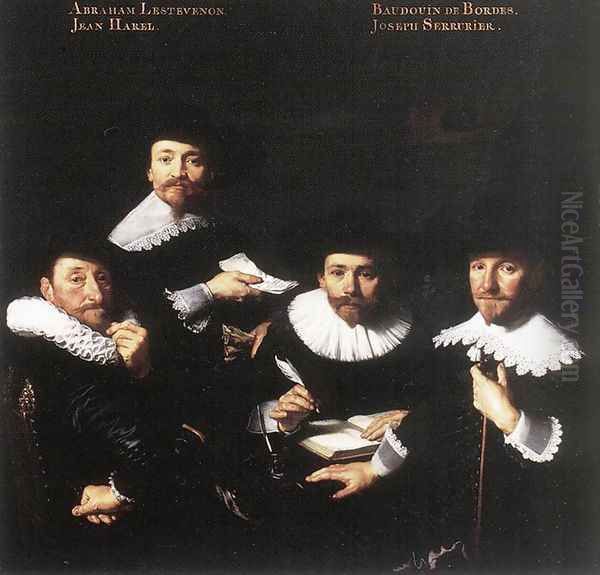

Another significant group portrait is The Governors of the Kloveniersdoelen (also known as The Wardens of the Longbowmen's Civic Guard), painted in 1653. This work again showcases his ability to manage complex compositions involving multiple figures, presenting each individual with clarity and dignity while creating a cohesive and engaging scene.

His earlier work, The Regents of the Walloon Orphanage (1637), is notable for its more Rembrandtesque qualities in lighting and mood, demonstrating his early engagement with the master's style before developing his own distinct path. Individual portraits, such as Boy with a Spoon (1643), also highlight his skill in capturing personality and fine detail on a smaller scale. He also painted numerous portraits for Amsterdam's civic guard companies throughout his career.

Patronage, Success, and Recognition

Van der Helst became the portraitist of choice for Amsterdam's ruling class and wealthy elite. Prominent families like the Bickers, Witsens, and Huydecopers commissioned works from him, cementing his status within the city's social and artistic hierarchy. His ability to deliver elegant, flattering, yet lifelike portraits ensured a steady stream of commissions.

His success translated into considerable wealth. Contemporary commentators like the German painter and writer Joachim von Sandrart noted that Van der Helst's portraits "earned him a lot of money." Similarly, the Dutch artist biographer Arnold Houbraken remarked on his financial success. This prosperity reflected his high standing and the great demand for his work. His fame extended beyond the Dutch Republic; he notably received a commission to paint a portrait of Mary Stuart, likely referring to Mary, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange, wife of William II, Prince of Orange, further enhancing his international reputation.

Relationship with Contemporaries

While Van der Helst operated within the vibrant artistic milieu of 17th-century Amsterdam, a city teeming with talent, there is no specific documentary evidence of direct personal collaboration or close friendships with figures like Rembrandt or Johannes Vermeer. Although their careers overlapped significantly in time and place, particularly with Rembrandt, their stylistic paths diverged, catering to different, though sometimes overlapping, segments of the art market.

His connection to Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy seems primarily that of a student, absorbing aspects of his teacher's approach to portraiture early on. The influence of Rembrandt is evident, especially in the 1630s, but Van der Helst consciously cultivated a different aesthetic. Comparisons were inevitably made, particularly regarding group portraits, with some contemporaries favouring Van der Helst's clarity.

He was certainly aware of other successful Amsterdam painters like Govert Flinck and Ferdinand Bol, both pupils of Rembrandt who also achieved great success with a more polished style. The elegant court portraits of Anthony van Dyck, though primarily active elsewhere, set an international standard for aristocratic portraiture that likely resonated with the tastes Van der Helst served. While direct interactions aren't recorded with Vermeer, whose known associates included Carel Fabritius and Samuel van Hoogstraten, the Dutch art world was interconnected, and artists were undoubtedly aware of each other's work. Van der Helst's own influence extended to later artists, including the marine painter Ludolph Backhuysen.

Beyond Portraiture

Although renowned primarily for his portraits, Van der Helst demonstrated his versatility by occasionally venturing into other genres. He produced a number of genre scenes, depicting aspects of everyday life, as well as paintings based on biblical narratives and mythological subjects. While these works form a smaller part of his oeuvre compared to his portraits, they showcase a broader range of artistic interests and abilities, further rounding out our understanding of his talents.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

Bartholomeus van der Helst remained a dominant force in Amsterdam portraiture through the 1650s and 1660s. He continued to receive important commissions and maintained his high reputation until his death in Amsterdam on December 16, 1670. He was buried in the Walloon Church (Waalse Kerk).

His legacy is significant. For decades, he set the standard for fashionable portraiture in the Dutch Republic's wealthiest city. His technical mastery, particularly in rendering textures and capturing likenesses with an air of refined elegance, was widely admired. His influence persisted, shaping portrait painting conventions in the Netherlands well into the later 17th century and beyond, with echoes noticeable even into the 19th century. He remains a key figure for understanding the artistic tastes and social aspirations of the Dutch Golden Age elite.

Provenance, Market, and Controversies

Many of Van der Helst's works are now held in major museum collections. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, fittingly, holds several of his most important pieces, including the celebrated Banquet of the Amsterdam Civic Guard in Celebration of the Peace of Münster. The Amsterdam Museum houses his 1650 painting The Regents of the Spinhuis (Governors of the women's house of correction). Another work, sometimes titled Sick Boy, has a poignant history: confiscated by the Nazis from an Amsterdam gallery during World War II, it was later recovered by the Allied forces' Monuments Men and is now in the Dutch national collection (Rijksmuseum).

His works occasionally appear on the art market. In 2018, a portrait attributed to his circle depicting Admiral Willem van der Zaan was sold at Sotheby's in New York for a modest sum (€2000-€3000), suggesting it might have been a minor work or workshop piece. Other works, like a civic guard portrait (seen at auction in 2017) and a portrait of Mayor Andries Bicker and his family (seen in 2014), have also surfaced, though their sale prices were not always publicly reported.

Like many works with complex histories, some of Van der Helst's paintings have been subject to ownership disputes related to Nazi looting. The Portrait of a Man (1647) became the focus of a significant controversy. Looted during the war, it reappeared at the Viennese auction house Im Kinsky. Despite claims by the auction house regarding their legal right to sell under Austrian law, the heirs of the original Jewish owners strongly contested the sale, demanding restitution. This case highlights the ongoing legal and ethical challenges surrounding art displaced during the Nazi era.

Art Historical Evaluation and Debates

In the annals of art history, Bartholomeus van der Helst is firmly established as a leading portraitist of his era. His technical skill is undeniable, particularly his mastery of capturing likenesses, rendering fabrics, and composing large, complex group scenes with clarity and animation. His Banquet of the Amsterdam Civic Guard is consistently ranked among the masterpieces of Dutch Golden Age painting.

However, his evaluation has not been without nuance or debate. Some critics, particularly in later periods influenced by Romanticism, found his work perhaps too polished, too focused on the superficialities of wealth and status, lacking the deeper psychological introspection found in Rembrandt's portraits. His immense popularity and alignment with the fashionable tastes of his time have sometimes led to accusations of prioritizing commercial success over profound artistic exploration.

Questions regarding originality have also surfaced, particularly concerning the influence of his likely teacher, Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy. While influence is natural, the discussion touches upon the balance between adopting established conventions and forging a unique artistic identity. Furthermore, the controversy surrounding looted works like the Portrait of a Man adds a layer of ethical complexity to the study of his oeuvre, reminding us that artworks carry histories far beyond their aesthetic qualities.

Despite these debates, Van der Helst's importance remains secure. He was a master technician whose works provide an invaluable visual record of the Dutch elite during a period of unprecedented prosperity. His elegant style defined portraiture in Amsterdam for decades, influencing countless contemporaries and successors. His ability to satisfy his patrons while maintaining a high level of artistic quality ensured his place as a central figure in 17th-century Dutch art.

Conclusion: A Mirror to an Age

Bartholomeus van der Helst was more than just a painter; he was a chronicler of the Dutch Golden Age's elite. His canvases reflect the confidence, wealth, and social intricacies of Amsterdam during its zenith. Through his elegant brushwork, meticulous detail, and skillful compositions, he captured the likenesses and aspirations of the men and women who shaped the Dutch Republic. While debates about influence and depth may continue, his technical brilliance and his role as the premier portraitist for a generation of powerful patrons solidify his enduring importance in the history of art. His works remain compelling windows into a fascinating and prosperous chapter of European history.