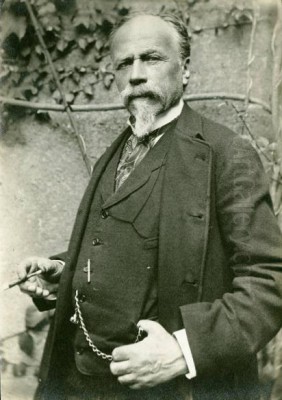

Bartolomeo Giuliano stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century Italian art. Born in Susa, Piedmont, in 1825, and passing away in Milan in 1909, Giuliano's career spanned a period of profound transformation in Italy, both politically and artistically. He dedicated himself primarily to genre painting, capturing the nuances of everyday life with a distinctive elegance and meticulous attention to detail. His work offers a valuable window into the social fabric and artistic currents of his time, reflecting both the enduring legacy of Italian artistic traditions and the emerging sensibilities of a modernizing nation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

The mid-nineteenth century in Italy was a crucible of change. The Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification, was gaining momentum, and with it came a renewed sense of national identity that often found expression in the arts. Artists were increasingly looking to depict Italian life and landscapes, moving away from purely classical or religious themes, or reinterpreting them through a more contemporary lens. It was into this dynamic environment that Bartolomeo Giuliano was born.

While specific details about Giuliano's earliest artistic training are not extensively documented, it is highly probable that he received a formal academic education. Art academies, such as the Accademia Albertina in Turin (the regional capital of Piedmont), were the primary institutions for artistic instruction. These academies emphasized rigorous training in drawing from life and from classical casts, perspective, anatomy, and the study of Old Masters. The influence of Renaissance titans like Raphael, with his harmonious compositions and idealized beauty, and Baroque masters such as Caravaggio, renowned for his dramatic realism and chiaroscuro, formed a foundational part of the academic curriculum, even for artists who would later develop more individualized styles.

Giuliano's formative years would have exposed him to these classical traditions, instilling in him a respect for technical skill and careful observation. However, the nineteenth century also saw the rise of Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion and individualism, and later, Realism, which sought to depict the world truthfully, without idealization. These currents would undoubtedly have played a role in shaping his artistic outlook.

The Essence of Genre Painting in Giuliano's Work

Bartolomeo Giuliano carved his niche in genre painting, a field that focuses on scenes of everyday life. This was a popular category in the nineteenth century, appealing to a growing middle-class clientele who appreciated depictions of familiar activities, social interactions, and sentimental moments. Giuliano excelled in this domain, bringing a refined sensibility to his subjects. His canvases often portray bustling market scenes, quiet domestic interiors, rural laborers, or moments of leisure and contemplation.

His approach was characterized by an elegant and detailed realism. He possessed a keen eye for the particulars of costume, setting, and human gesture, rendering them with a fine brush and a subtle understanding of light and texture. Unlike some of his contemporaries who might have leaned towards more overt social commentary or dramatic narratives, Giuliano's work often exudes a sense of quiet observation and gentle empathy. He seemed less interested in grand historical statements and more focused on the intimate, human scale of daily existence.

The figures in his paintings are not mere archetypes but individuals with discernible emotions. He skillfully conveyed their inner states through subtle facial expressions, body language, and the direction of their gaze. This ability to imbue his scenes with psychological depth, even in seemingly mundane settings, elevates his work beyond simple illustration. Viewers are invited not just to observe, but to connect with the people and stories depicted.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Several works help to illustrate Bartolomeo Giuliano's artistic contributions and thematic interests. While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be elusive, certain paintings are frequently associated with his name and exemplify his style.

One of his most discussed later pieces is "Le Vili," reportedly exhibited at the National Fine Arts Exhibition in Milan in 1906. This painting draws its inspiration from Slavic folklore, specifically the legend of the Vili (or Wilis) – the spirits of young women who died before their wedding day, jilted or betrayed, and who rise at night to dance and lure young men to their deaths. The choice of such a theme suggests a departure, or at least an expansion, from purely realistic genre scenes into the realm of Romanticism or even early Symbolism. It indicates an interest in folklore, the supernatural, and the more mysterious aspects of human emotion and legend. This work would have resonated with the Symbolist currents prevalent in European art at the turn of the century, explored by artists like Arnold Böcklin or Giovanni Segantini, though Giuliano's interpretation would likely retain his characteristic finesse.

Another piece attributed to him is "Fanciulla pensosa in parco" (A Pensive Young Woman in a Park). This title evokes a common nineteenth-century motif: the solitary female figure in a natural setting, lost in thought. Such paintings often carried sentimental or romantic connotations, exploring themes of introspection, longing, or the quiet beauty of nature. Giuliano's treatment would likely emphasize the delicate rendering of the figure and the atmospheric quality of the park setting, capturing a fleeting moment of private contemplation. This type of subject was popular across Europe, seen in the works of artists ranging from the Pre-Raphaelites in Britain to academic painters in France like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, though Italian interpretations often had their own distinct flavor.

The mention of a "View of Lake Maggiore" also points to his engagement with landscape painting, or at least genre scenes with significant landscape elements. The Italian lakes were, and remain, a popular subject for artists, offering picturesque vistas and a sense of romantic allure. Such a work would have allowed Giuliano to showcase his skills in rendering natural light, water, and atmospheric perspective, perhaps populating the scene with figures engaged in local activities, thereby blending landscape with genre. Artists like Giuseppe De Nittis, though more aligned with Impressionistic tendencies, also captured the beauty of Italian landscapes and cityscapes, reflecting a broader interest in depicting the national environment.

His broader oeuvre likely included numerous scenes of Italian markets, peasant life, and urban interactions. These subjects were staples for genre painters of the era, including contemporaries like Antonio Rotta or Giacomo Favretto, who also specialized in Venetian and Italian everyday life, often with a touch of humor or social observation. Giuliano's contribution would be marked by his particular blend of detailed execution and refined sentiment.

Artistic Influences and Contemporary Context

Bartolomeo Giuliano's art did not develop in a vacuum. He was part of a rich and evolving Italian artistic tradition. While direct tutelage under specific masters is not always clear, the general influences are discernible. The academic grounding, as mentioned, would have included the study of Renaissance masters like Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci for their principles of composition, grace, and anatomical understanding. The dramatic realism and use of light by Caravaggio and his followers (the Caravaggisti) also left an indelible mark on Italian art, aspects of which could be adapted even by nineteenth-century realists.

In the context of nineteenth-century Italy, several artistic movements and figures are relevant. The Macchiaioli, active primarily in Tuscany from the 1850s, were a group of painters who reacted against academic conventions, emphasizing painting outdoors ("en plein air") and using patches or "macchie" of color to capture the effects of light and shadow. Key figures included Giovanni Fattori, Telemaco Signorini, and Silvestro Lega. While Giuliano's style appears more polished and detailed than the often sketchier approach of the Macchiaioli, their commitment to depicting contemporary Italian life and landscape was part of the same broader cultural shift.

In Lombardy, where Giuliano spent his later years (Milan), artists like Francesco Hayez had been dominant figures in the earlier part of the century, known for his Romantic historical paintings and portraits. Later, the Scapigliatura movement emerged in Milan, characterized by a bohemian spirit and an anti-academic stance, often with a more experimental and emotionally charged style. While Giuliano may not have been a direct participant, these movements contributed to the artistic ferment of the region.

Looking at genre painting specifically, artists like Domenico Induno in Milan were known for their depictions of everyday life, often with a focus on social themes and the lives of the common people. Further south, in Naples, Domenico Morelli was a leading figure whose work spanned historical subjects, religious themes, and Orientalist scenes, often with a dramatic and richly colored style.

Beyond Italy, European genre painting was thriving. The influence of seventeenth-century Dutch masters like Jan Steen or Adriaen van Ostade, with their lively and detailed scenes of peasant life and bourgeois interiors, had long been appreciated and emulated. In the nineteenth century, French academic painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme or the aforementioned William-Adolphe Bouguereau produced highly finished genre and historical scenes, though often with a different sensibility than the more intimate Italian examples. The broader European trend towards realism also played a role, with figures like Gustave Courbet in France championing the depiction of unidealized contemporary subjects.

Giuliano's work, therefore, can be seen as navigating these various influences: a foundation in academic tradition, an engagement with the popular demand for genre scenes, and an awareness of the broader currents of Romanticism and Realism that characterized his century.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Personal Life

The mention of Giuliano's participation in the 1906 National Fine Arts Exhibition in Milan with "Le Vili" is an important marker of his professional activity. Such national exhibitions were crucial platforms for artists to showcase their work, gain recognition, and attract patrons. Participation implied a certain level of established reputation.

Beyond this, detailed records of his exhibition history or specific accolades are not as widely publicized as those of some of his more famous contemporaries. This aligns with the observation that information about his personal life and the minutiae of his career is relatively scarce. It's possible he was an artist who preferred a more private existence, focusing on his craft rather than actively cultivating a public persona. This was not uncommon; many skilled artists contributed significantly to the cultural fabric of their time without achieving the widespread fame of a select few.

His long life, spanning from 1825 to 1909, meant he witnessed immense changes in Italy: from a collection of disparate states to a unified kingdom, and from a largely agrarian society to one beginning to embrace industrialization. These societal shifts inevitably impacted the arts, from patronage systems to the subjects deemed worthy of depiction. Giuliano's dedication to genre painting throughout this period suggests a consistent artistic vision, focused on capturing the enduring human elements within a changing world.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Bartolomeo Giuliano's legacy lies in his contribution to the rich tapestry of nineteenth-century Italian genre painting. He was a skilled practitioner who brought a characteristic elegance and sensitivity to his depictions of everyday life. His works serve as valuable historical documents, offering insights into the customs, attire, and social environments of his era.

While he may not be as internationally renowned as some of his Italian contemporaries like Giovanni Boldini or Giuseppe De Nittis, who achieved fame in Paris, Giuliano's art holds a significant place within the Italian national context. He represents a strand of nineteenth-century realism that was less about radical social critique or avant-garde experimentation and more about the careful, empathetic observation of humanity. His paintings are appreciated for their technical accomplishment, their charming subject matter, and their ability to evoke a sense of connection with the past.

The enduring appeal of his work, particularly pieces like "Le Vili" with its intriguing folkloric theme, or the more typical "Fanciulla pensosa in parco," demonstrates his versatility and his capacity to engage with different facets of the human experience, from the everyday to the imaginative. For art historians and enthusiasts of nineteenth-century European art, Bartolomeo Giuliano remains an artist worthy of study and appreciation, a testament to the quiet power of genre painting to capture the spirit of an age. His dedication to his craft over a long career ensured a body of work that continues to resonate with those who appreciate finely rendered scenes of life, imbued with a subtle and enduring charm.