Pietro Pajetta stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century Italian art. An artist deeply rooted in the traditions of his homeland, Pajetta carved a niche for himself through his poignant depictions of everyday life, his insightful exploration of human emotion, and his ability to convey complex narratives within a single frame. His work, often characterized by a somber palette and dramatic intensity, offers a window into the social realities and psychological undercurrents of his time. This exploration delves into the life, career, artistic style, and enduring legacy of Pietro Pajetta, an Italian painter whose contributions merit closer examination.

The Artist's Origins and Early Life

Pietro Pajetta was born in Serravalle, a locality within Vittorio Veneto in the province of Treviso, Italy, on March 22, 1845. This period in Italian history was one of significant political and social upheaval, with the stirrings of the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification, gaining momentum. Growing up in the Veneto region, an area rich in artistic heritage, Pajetta would have been immersed in a culture that revered the masters of the Venetian School, from Titian and Tintoretto to later figures like Giambattista Tiepolo. While specific details about his early childhood and familial background are not extensively documented, it is reasonable to assume that the artistic environment of Veneto played a formative role in shaping his nascent sensibilities.

His primary sphere of activity later centered around Padua, another city with a distinguished artistic and intellectual history, home to Giotto's Scrovegni Chapel and a university that was a beacon of learning. The move to Padua likely provided Pajetta with greater opportunities for artistic development and engagement with a broader cultural milieu. The exact timeline of his relocation and the specific circumstances that led him there remain somewhat obscure, but Padua became the city where he would ultimately spend his final years.

Formative Years and Artistic Education

Information regarding Pietro Pajetta's formal artistic training and his principal mentors is not explicitly detailed in many historical accounts. However, for an aspiring painter in 19th-century Italy, the path typically involved apprenticeship under an established master or enrollment in one of the prominent art academies. The Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia (Academy of Fine Arts of Venice) was, and remains, a preeminent institution, and it is plausible that Pajetta received some instruction there or was at least influenced by its teachings and the artists associated with it. Artists like Francesco Hayez, a leading figure of Italian Romanticism, had a profound impact on academic art in Northern Italy during the mid-19th century.

Alternatively, Pajetta might have sought training in Florence or Rome, though his strong association with Veneto and Padua suggests his formative experiences were likely concentrated in Northern Italy. The curriculum at these academies would have emphasized drawing from life and from classical sculpture, the study of anatomy, perspective, and the techniques of the Old Masters. Regardless of the specifics of his formal education, Pajetta's work demonstrates a solid grounding in academic principles, particularly in figure drawing and composition, which he later adapted to his own expressive ends. His development was also undoubtedly shaped by the prevailing artistic currents of his time, including the lingering influence of Romanticism and the rise of Realism, which encouraged artists to depict contemporary life with truthfulness.

Service in the Wars of Independence and Economic Hardships

A significant, though not extensively detailed, aspect of Pajetta's life was his service during the Italian Wars of Independence. These conflicts, spanning several decades in the mid-19th century, were pivotal in the unification of Italy. While the specific campaigns or units Pajetta served with are not widely recorded, the experience of war invariably leaves a profound mark on an individual. For an artist, such experiences can translate into a deeper understanding of human suffering, resilience, and the dramatic intensity of life and death – themes that resonate in some of Pajetta's more emotionally charged works.

The period following the wars and throughout much of his career was also marked by economic instability in Italy. The newly unified nation faced considerable challenges in modernizing its economy and integrating disparate regions. Artists, like many others, often contended with financial difficulties. The provided information notes that Pajetta experienced such periods of economic instability. These hardships may have influenced his choice of subject matter, perhaps drawing him towards scenes of everyday life and the struggles of ordinary people, which could find a more receptive, if not always lucrative, market. It also speaks to his perseverance as an artist, continuing to create despite challenging circumstances. The ability to transform personal and societal struggles into compelling visual narratives is a hallmark of his mature work.

One source mentions that this economic instability was particularly acute between 1848 and 1851, a period encompassing the First Italian War of Independence and its aftermath. This timeframe aligns with Pajetta's very early years, suggesting that the socio-economic climate of his childhood and youth was one of considerable turmoil. Later, Italy, like other nations, faced economic crises, including those in the late 19th century and the period leading up to and including the Great Depression, although the latter would have been towards the very end of his life or posthumously, depending on the correct death year. The source text also mentions the Great Depression of 1929, which is well after Pajetta's death in 1911, indicating a possible conflation of general Italian economic history with Pajetta's specific circumstances or a misunderstanding of timelines. The primary period of economic hardship relevant to his active career would be the latter half of the 19th century.

Artistic Style: Realism, Emotion, and the Venetian Legacy

Pietro Pajetta is best known as a painter of genre scenes, depicting moments from rural and everyday life. His style, while rooted in academic tradition, evolved to incorporate elements of Realism, a movement that gained traction across Europe in the mid-to-late 19th century. Realism, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet in France, sought to portray the world and its inhabitants without idealization, focusing on the tangible realities of contemporary existence. In Italy, this trend manifested in various regional forms, including the work of the Macchiaioli in Tuscany, who, while distinct in their technique, shared a commitment to depicting modern life.

Pajetta’s particular strength lay in his ability to imbue these everyday scenes with profound emotional depth and psychological insight. He was not merely a chronicler of customs and costumes; he was an observer of the human condition. His figures, often peasants or common folk, are rendered with a sense of dignity and an awareness of their inner lives. He excelled at capturing subtle gestures, facial expressions, and interactions that convey a range of emotions, from quiet contemplation and sorrow to moments of tension and drama.

His connection to the Venetian School is also apparent, particularly in his handling of color and light, though he often favored a more somber and dramatic palette than the luminous vibrancy typically associated with earlier Venetian masters. The Venetian tradition, with its emphasis on colorito (color) over disegno (drawing), and its rich history of narrative painting, provided a fertile ground for Pajetta's development. Artists like Giacomo Favretto, a contemporary Venetian genre painter, also explored scenes of everyday Venetian life, though often with a lighter, more anecdotal touch than Pajetta's more intense psychological dramas. Guglielmo Ciardi, another Venetian contemporary, focused more on landscapes and seascapes, but shared the regional sensitivity to light and atmosphere.

Pajetta's technique often involved strong chiaroscuro, creating dramatic contrasts between light and shadow that heighten the emotional impact of his scenes. His compositions are carefully constructed, guiding the viewer's eye to the focal point of the narrative. He was adept at creating a palpable atmosphere, whether it be the quiet intimacy of a domestic interior or the charged air of a brewing conflict.

"L'Odio" (The Hatred): A Masterpiece of Dramatic Intensity

Among Pietro Pajetta's works, "L'Odio" (often referred to by its German title "Der Hass" in some sources, meaning "The Hatred") stands out as his most renowned masterpiece. Painted in 1896, this powerful work exemplifies his ability to convey intense emotion and complex narrative through a single, arresting image. The painting depicts a dimly lit, somber interior. In the foreground, a man is shown kneeling, his head bowed in an attitude of profound grief, despair, or perhaps contemplation of a dark deed. Behind him, on a makeshift bier or bed, lies a figure entirely covered by a white sheet, unmistakably a corpse.

The scene is one of stark tragedy. The composition is theatrical, focusing the viewer's attention on the raw emotion of the kneeling figure and the silent, unsettling presence of the deceased. The palette is dominated by dark, earthy tones, with the white of the shroud providing a stark contrast that emphasizes the finality of death. The lighting is dramatic, illuminating key elements while leaving much of the scene in shadow, adding to the sense of mystery and foreboding.

"L'Odio" is a profound meditation on the theme of vengeance and its devastating consequences. The source material indicates that the painting was inspired by the poem "Canto dell'Odio" (Song of Hatred) from the "Postuma" collection by Lorenzo Stecchetti, the pseudonym of the Italian poet Olindo Guerrini (1845-1916). Guerrini's work, part of the Verismo literary movement which paralleled Realism in art, often explored themes of passion, betrayal, and the darker aspects of human nature. The poem reportedly tells the story of a spurned lover who exacts revenge upon the corpse of his unfaithful beloved. Pajetta's painting masterfully translates this literary inspiration into a visual language of immense power, capturing the desolation and destructive force of hatred.

The painting's critical reception and its enduring impact underscore Pajetta's skill in tackling such challenging and profound themes. It is a work that transcends mere genre painting, entering the realm of psychological portraiture and social commentary. The raw emotionality and dramatic staging of "L'Odio" align it with a broader European interest in Symbolism and psychological realism that characterized the fin de siècle. Artists like Edvard Munch, with his explorations of anxiety and despair, were also pushing the boundaries of emotional expression in art around this time, albeit with a different stylistic vocabulary.

Other Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

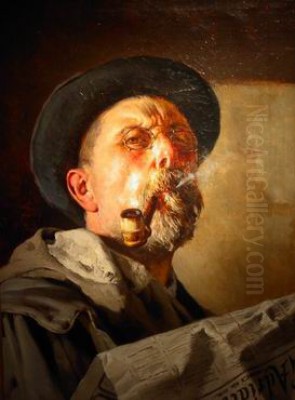

While "L'Odio" is his most celebrated piece, Pietro Pajetta produced a body of work that explored various facets of human experience. His "Autoritratto" (Self-Portrait), mentioned in the provided texts, would offer invaluable insight into how the artist saw himself and wished to be perceived. Self-portraits are often deeply personal statements, revealing not only the artist's likeness but also aspects of their character and artistic identity. Unfortunately, without wider access to an image or detailed descriptions of this self-portrait, a full analysis is limited, but its existence points to a practice common among artists for self-examination and presentation.

The source material also mentions a portrait of "Lorenzo Da Ponte" and its connection to Mozart. This claim is highly problematic. Lorenzo Da Ponte (1749-1838) was Mozart's (1756-1791) librettist. Pietro Pajetta was born in 1845, seven years after Da Ponte's death and more than half a century after Mozart's. It is chronologically impossible for Pietro Pajetta to have painted Da Ponte from life or for such a portrait to be noted for a friendship with Mozart involving Pajetta. This information is almost certainly an error, perhaps a misattribution, a reference to a copy of an earlier portrait, or confusion with a different artist entirely. Given the instruction not to omit information, it is mentioned here, but with the strong caveat of its historical implausibility concerning this Pietro Pajetta.

Pajetta's oeuvre primarily consisted of genre scenes. These would have included depictions of rural labor, domestic interiors, village gatherings, and moments of personal reflection or interaction. These works, while perhaps less overtly dramatic than "L'Odio," would still have showcased his keen observation, his empathy for his subjects, and his ability to tell a story through visual means. He was part of a broader tradition of Italian genre painting that included artists like Antonio Rotta, known for his Venetian scenes, and Vincenzo Cabianca, one of the Macchiaioli who also depicted everyday life. Further afield, the works of French realists like Jean-François Millet, with his dignified portrayals of peasant life, or Dutch 17th-century genre painters, offer parallels in their focus on the common man.

The themes in Pajetta's work often revolved around the realities of life for the less privileged classes, touching upon toil, poverty, simple pleasures, and the enduring strength of the human spirit. His paintings likely resonated with a public increasingly interested in depictions of contemporary life, moving away from the grand historical or mythological subjects that had dominated academic art for centuries.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Artistic Connections

Pietro Pajetta's works were exhibited in various venues, contributing to his recognition within the Italian art world. The provided information lists several specific locations:

Galleria Civica d'Arte Medievale, Moderna e Contemporanea "Vittorio Emanuele II": The inclusion of his work in such a civic gallery, likely in Vittorio Veneto or a similar regional center, indicates a level of established reputation. The mention of other artists like Alessandro Pomi and Pino Casarini being exhibited alongside him helps to place Pajetta within a cohort of regional artists of note.

Museo del Cenedese e Oratorio Dei SS. Lorenzo e Marco Dei Battuti (Vittorio Veneto): This museum, located in Pajetta's native region, holds significant works, including "L'Odio" ("Odio" in Italian). The presence of a dedicated "Pajetta room" or significant holdings within the Museo del Cenedesi, as mentioned in the source, underscores his local importance and the esteem in which his work is held there. The museum's expansion in 2002, which included further display of his works, speaks to a continued appreciation of his art.

Participation in exhibitions was crucial for artists of Pajetta's era to gain visibility, attract patrons, and engage in critical discourse. While the provided text does not specify participation in major national or international expositions like the Venice Biennale (established in 1895, so within his active period), his regional exhibitions were vital.

Regarding his connections with other painters, the source material suggests he was largely an independent artist, without strong documented ties to specific artistic groups or extensive collaborations. However, he was undoubtedly aware of and influenced by his contemporaries. The text mentions that his work, particularly "Der Hass," shows stylistic similarities or shared thematic concerns with painters like Luigi Serrai and Paolo Antootti, suggesting they were part of a similar artistic current focusing on social issues and dramatic representation. Further research into these specific artists could illuminate the artistic environment in which Pajetta operated. The broader Italian art scene of the late 19th century was vibrant, with figures like Giovanni Segantini exploring Symbolism in Alpine settings, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo creating iconic works of social realism like "The Fourth Estate," and Antonio Mancini known for his thickly impastoed, psychologically penetrating portraits. While Pajetta's style was his own, he was part of this rich tapestry of Italian art.

The Social and Political Context: A Man of His Times

Pietro Pajetta lived through a transformative period in Italian history. The unification of Italy (the Risorgimento) was achieved during his youth and early adulthood, but the new nation faced immense challenges: regional disparities, economic struggles, political instability, and social unrest. His service in the Wars of Independence would have directly immersed him in the nationalistic fervor and the sacrifices involved in nation-building.

The provided text mentions that Pajetta's life experiences, including his military service and periods of economic instability, enabled him to translate complex emotions into visual narratives. This suggests an artist deeply engaged with the realities of his time. His focus on genre scenes, often depicting the lives of ordinary people, can be seen as a reflection of the Verismo movement in literature and art, which emphasized a truthful and often unvarnished portrayal of contemporary life, particularly that of the lower classes.

It is crucial here to address a point of significant confusion in the provided source material. Several passages attribute social and political activities, particularly involvement with the Italian Communist Party, resistance movements during World War II, and post-war political speeches, to "Pietro Pajetta." This is a clear conflation with Giancarlo Pajetta (1911-1990), a prominent Italian communist politician and partisan leader. Giancarlo Pajetta was born the year Pietro Pajetta (the painter, 1845-1911) died. Therefore, all references to communist activities, WWII resistance, and speeches against government corruption in the context of "Pietro Pajetta" are anachronistic and misattributed. Pietro Pajetta the painter was a man of the 19th and early 20th century; his social commentary was primarily expressed through his art, reflecting the conditions and sensibilities of his era, not the mid-20th century political struggles of Giancarlo Pajetta.

The Peter Pajetta Square in Turin, mentioned as originally being an open area outside the Porta Torino, is another piece of information that requires careful handling. While the name exists, its direct connection to Pietro Pajetta the painter (1845-1911), whose main centers of activity were Serravalle and Padua, is not immediately evident without further specific research. It could be named after him, or another individual named Pajetta.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Pietro Pajetta continued to paint into the early 20th century. He passed away in Padua on April 10, 1911. This date is generally accepted, although one section of the provided source material confusingly states his death year as 1899, while also mentioning his name appearing in a publication on September 1, 1899, as evidence of his activity before that date. The 1845-1911 dates are more consistent with an artist producing a major work like "L'Odio" in 1896 and being considered a figure of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The 1899 death date is likely an error or refers to a different individual.

Pietro Pajetta's legacy resides primarily in his powerful genre paintings, especially "L'Odio," which remains a compelling work of art. His contribution to the Venetian and broader Italian art scene lies in his ability to blend academic skill with a realist's eye for detail and a romantic's sensitivity to emotion. He captured the human condition with an honesty and intensity that continues to resonate.

His works are preserved in regional museums, particularly in the Veneto, ensuring that his art remains accessible to the public in the areas where he lived and worked. While he may not have achieved the international fame of some of his Italian contemporaries like Giovanni Boldini or Medardo Rosso, Pajetta holds an important place in the narrative of Italian art of his period. He represents a strand of Italian painting that was deeply concerned with local realities, human psychology, and the expressive power of art to convey profound truths about life.

His influence can be seen in the continuation of realist and expressive traditions in Italian art. Artists who continued to explore the human figure and narrative painting in the 20th century, even as modernism took hold, built upon the foundations laid by painters like Pajetta, who insisted on the enduring relevance of human experience as a subject for art.

Conclusion: Reappraising Pietro Pajetta

Pietro Pajetta was an artist of considerable talent and depth, whose work merits greater recognition beyond specialized circles. Born into an era of national formation and social change, he navigated personal hardships and the shifting currents of the art world to create a body of work characterized by its emotional honesty and dramatic power. His masterpiece, "L'Odio," is a testament to his ability to tackle profound themes of human passion and suffering with unflinching intensity.

As a painter of genre scenes, he elevated the depiction of everyday life beyond mere anecdote, infusing his subjects with dignity and psychological complexity. His roots in the Venetian artistic tradition, combined with an engagement with the broader European movement of Realism, resulted in a distinctive style that was both grounded in observation and heightened by a keen sense of drama.

While some details of his life and career remain to be fully illuminated, and while some information provided in the source texts presents clear contradictions or misattributions (particularly concerning political activities and certain biographical details like the Da Ponte portrait or the definitive death year), the core of his artistic achievement is undeniable. Pietro Pajetta's paintings offer a compelling glimpse into the soul of late 19th and early 20th-century Italy, and his contribution to the rich tapestry of Italian art endures. He remains a significant figure for those who appreciate art that speaks with sincerity, skill, and a deep understanding of the human heart.