Basilius Besler stands as a pivotal figure at the intersection of botany, pharmacology, and art during the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods in Germany. His life and work, particularly his magnum opus, `Hortus Eystettensis`, not only captured the burgeoning scientific interest in the natural world but also set a new standard for botanical illustration, influencing generations of artists and scientists. His story is one of meticulous observation, artistic collaboration, and the patronage that fueled such ambitious undertakings.

Early Life and Foundations in Nuremberg

Born on February 13, 1561, in the thriving Imperial Free City of Nuremberg, Basilius Besler was immersed in an environment rich in artistic and intellectual traditions. Nuremberg, a hub of the German Renaissance, had been home to luminaries like Albrecht Dürer, whose keen eye for natural detail left an indelible mark on German art. Besler's father, Michael Besler, was an apothecary, a profession that inherently combined knowledge of plants with medicinal practice. This familial background undoubtedly shaped young Basilius's interests.

He followed in his father's footsteps, becoming an apothecary himself. This profession required an intimate understanding of herbs and their properties, fostering a deep connection with the plant kingdom. Besler established his own pharmacy, "Zum Marienbild" (At the Sign of the Virgin Mary), in Nuremberg. Beyond his pharmaceutical practice, he cultivated a personal botanical garden at his home on the Heumarkt and amassed a significant natural history collection, or Kunstkammer, which was fashionable among intellectuals and the wealthy of the era. His reputation grew, and in 1594, he was elected to the Nuremberg city council, indicating his respected standing within the community.

The Patronage of a Prince-Bishop: The Eichstätt Garden

Besler's most significant undertaking, and the one for which he is most renowned, began with a prestigious commission. Around 1597 or 1598, Johann Konrad von Gemmingen, the Prince-Bishop of Eichstätt in Bavaria (born circa 1561, died 1612), embarked on an ambitious project to create a magnificent botanical garden around his palace, the Willibaldsburg. This was an era when botanical gardens were symbols of power, learning, and an appreciation for God's creation. The Prince-Bishop, a man of considerable learning and taste, aimed to create one of the most impressive gardens in Europe.

To manage and document this horticultural marvel, Johann Konrad von Gemmingen appointed Basilius Besler. The garden itself was a testament to the expanding global knowledge of the time, featuring not only native European species but also exotic plants recently introduced from Asia, Africa, and the Americas. It was divided into eight distinct sections, reflecting the diversity of its collection, which included an estimated 1084 different plant species by the time of its documentation. Besler's role was not just curatorial; he was tasked with creating a comprehensive visual record of this extraordinary collection.

`Hortus Eystettensis`: A Botanical Masterpiece

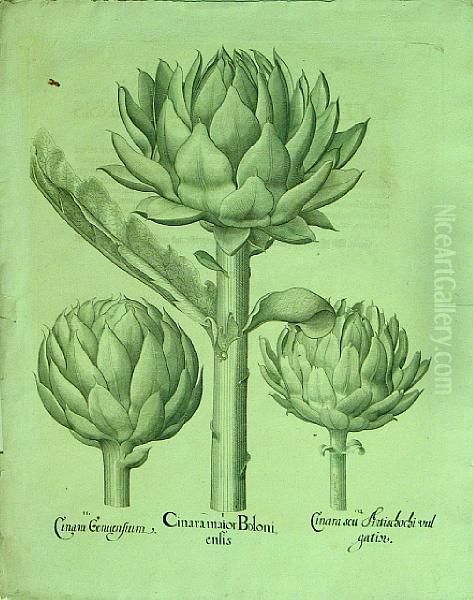

The fruit of this commission was the `Hortus Eystettensis` (The Garden of Eichstätt), first published in 1613. This monumental work is considered one of the glories of botanical literature and art. It was an incredibly ambitious project, taking approximately sixteen years from its conception to the first printing. The book was designed to be a florilegium, a collection of illustrations of flowers, rather than a strictly scientific herbal in the tradition of Leonhart Fuchs's `De Historia Stirpium` (1542), though its accuracy was paramount.

The `Hortus Eystettensis` comprised 367 copperplate engravings, depicting 1084 individual plant species. Many plates featured multiple plants, often grouped by season or aesthetic appeal rather than strict botanical classification, though a seasonal arrangement (Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter flowering plants) provided its overarching structure. This seasonal organization was an innovative approach for its time, offering a dynamic view of the garden throughout the year. Each plant was meticulously rendered, often shown life-size or close to it, with remarkable attention to detail in its flowers, leaves, stems, and sometimes roots. Latin names and brief descriptions accompanied the illustrations.

The sheer scale of the `Hortus Eystettensis` was unprecedented for a florilegium. It was printed on large folio sheets, making it a physically imposing volume. Two main versions were produced: a deluxe edition, printed on high-quality paper and lavishly hand-colored by skilled artisans, and a more affordable uncolored version. The colored versions were exceptionally expensive, costing around 500 florins, while the uncolored ones sold for about 35 florins. This indicates the high esteem in which such works were held, appealing to wealthy collectors, libraries, and fellow botanists.

Artistic Style and Scientific Accuracy

The artistic style of the `Hortus Eystettensis` is a hallmark of the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods. There is a clear emphasis on scientific accuracy, a legacy of earlier botanical artists like the aforementioned Leonhart Fuchs or the Swiss polymath Conrad Gessner, whose posthumously published botanical works also featured detailed woodcuts. However, Besler's work, through the medium of copperplate engraving, achieved a finer level of detail and a more sophisticated aesthetic.

The illustrations in `Hortus Eystettensis` are characterized by their clarity, precision, and elegance. Plants are typically depicted in their entirety or with significant portions shown, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of their morphology. While scientifically accurate, the compositions often possess a strong decorative quality. The arrangement of plants on the page, the graceful curves of stems and leaves, and the vibrant (in the colored editions) depiction of flowers all contribute to a sense of opulence and visual delight characteristic of the Baroque sensibility. This blend of scientific utility and aesthetic beauty was a key feature of the work.

Unlike some earlier herbals that might include stylized or somewhat crude representations, Besler's illustrations aimed for naturalism. The artists involved captured the texture of petals, the venation of leaves, and the subtle variations in plant forms. This dedication to verisimilitude made the `Hortus Eystettensis` an invaluable resource for botanists and gardeners, as well as a treasured art object. The sunflower plate, for instance, is often singled out for its "undisputed expressiveness" and powerful presence.

The Collaborative Nature of Creation

The creation of `Hortus Eystettensis` was a significant collaborative effort, orchestrated by Besler. While Besler himself was an amateur painter and likely made many of the initial sketches from live specimens in the Eichstätt garden, he employed a team of skilled artists and engravers to bring the project to fruition. His brother, Hieronymus Besler, also assisted in the project.

Among the primary artists involved was Sebastian Schedel, a painter from Nuremberg. Schedel is credited with creating many of the detailed drawings that served as the basis for the engravings. His ability to capture the unique characteristics of such a diverse array of plants was crucial to the project's success. These drawings were then translated into engravings, a highly skilled and labor-intensive process.

The majority of the engraving work was carried out in Augsburg, another major German artistic center, by Wolfgang Kilian and his workshop. Kilian was a prominent engraver, part of a well-known family of artists. Other engravers who contributed included Dominicus Custos (Kilian's stepfather and teacher), Raphael Custos (Dominicus's son), and Georg Gärtner. The skill of these engravers was paramount in transferring the nuances of the original drawings onto copper plates, ensuring that the printed images retained their detail and vitality. The process involved drawing the image in reverse onto the copper plate and then incising the lines with a burin. After Besler's death, some engraving work was reportedly continued in Nuremberg.

Besler's Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Basilius Besler operated within a vibrant artistic and intellectual landscape. The late 16th and early 17th centuries saw a flourishing of natural history studies and artistic representation across Europe. In the Netherlands, artists like Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601) were creating incredibly detailed and illusionistic depictions of flowers, insects, and small animals, often for wealthy patrons or as part of elaborate manuscripts. Hoefnagel's work for Emperor Rudolf II in Prague, for example, set a high bar for naturalistic detail.

The tradition of florilegia was also gaining popularity. The Crispijn van de Passe family of engravers (Crispijn the Elder, and his sons Simon, Crispijn II, and Willem, and daughter Magdalena) were active in Cologne and Utrecht, producing influential works like `Hortus Floridus` (1614) by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger, which appeared almost contemporaneously with Besler's masterpiece. These works catered to a growing interest in horticulture and the beauty of exotic plants.

While Besler focused on botanical subjects, the broader art world was transitioning into the Baroque. In Italy, Caravaggio (1571–1610) was revolutionizing painting with his dramatic use of chiaroscuro. In the Spanish Netherlands, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) was establishing himself as the preeminent Baroque painter, known for his dynamic compositions and rich colors. Though their subject matter differed, the underlying Baroque spirit of grandeur, detail, and a certain theatricality can be seen as a common thread.

In Germany itself, artists like Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610), though working primarily in Rome, were known for their meticulously detailed small-scale paintings. The legacy of Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) continued to resonate, particularly his pioneering work in printmaking and his intense studies of nature, such as "The Great Piece of Turf." Besler's work, therefore, can be seen as part of a broader European movement towards empirical observation and artistic excellence in depicting the natural world, building on the foundations laid by earlier masters and contributing to the evolving visual culture of his time. The painter Hans Simon Holtzbecker (active c. 1610-1671/72), known for his depictions of plants and insects, worked in a similar vein, and though direct interaction isn't heavily documented, their shared thematic concerns suggest a common artistic current.

Anecdotes and Intricacies of the `Hortus Eystettensis`

Several interesting details surround the `Hortus Eystettensis`. Prince-Bishop Johann Konrad von Gemmingen, the visionary patron, unfortunately, died in November 1612, just before the book's first publication in 1613. However, his commitment to the project ensured its completion, and his successors continued to value the garden and its documentation. The original copper plates, remarkably, survived for centuries. They were used for a second edition in 1640 (which omitted Besler's name and included a dedication to a new bishop) and a third edition in the 1750s. Tragically, the original plates were melted down at the Royal Mint in Munich in 1817.

The garden itself, the living inspiration for the book, suffered a worse fate. It was largely destroyed by invading Swedish troops under Landgrave Wilhelm V of Hesse-Kassel during the Thirty Years' War in 1633-34, just two decades after the book's publication. Thus, Besler's `Hortus Eystettensis` became an even more precious record of a lost botanical treasure.

Besler's personal life also saw him briefly venture into printing. He moved to Barmen in 1622 and became a printer in 1623, before returning to Nuremberg. He passed away on March 13, 1629, in Nuremberg, leaving behind a monumental legacy. His nephew, Michael Ruprecht Besler, continued his uncle's work to some extent, publishing `Mantissa ad Viretum Stirpium Eystettensium`, a supplement to the `Hortus Eystettensis`.

The Enduring Legacy and Influence

The `Hortus Eystettensis` had a profound and lasting impact. It was one of the earliest and most comprehensive florilegia, setting a benchmark for subsequent botanical publications. Its detailed and aesthetically pleasing illustrations were widely admired and copied, influencing the style of botanical art for centuries. Artists like Andrea Versanini are noted to have been influenced by Besler's work.

For botanists, the book was an important reference, documenting a vast array of species, including many newly discovered exotics. Its systematic, albeit seasonal, organization was also a step forward. While Linnaean taxonomy was still more than a century away, works like Besler's contributed to the growing body of knowledge that would eventually lead to more formal systems of classification.

The book's influence extended beyond the scientific community. The beauty of its plates appealed to artists, designers, and collectors. The images from `Hortus Eystettensis` have been reproduced in various forms over the centuries, appearing in decorative arts, textiles, and modern prints, a testament to their timeless appeal. The work stands as a prime example of the fruitful collaboration between patron, scientist-curator, and artists.

Later botanical artists, such as Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), who famously documented the insects and plants of Suriname, built upon the tradition of detailed natural observation and artistic skill exemplified by Besler and his contemporaries. Merian, like Besler, combined scientific inquiry with exceptional artistic talent, further advancing the field of natural history illustration. The meticulousness of Dutch flower painters like Jan van Huysum (1682–1749) or Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750), though working in oil paint rather than print, also reflects the era's fascination with botanical accuracy and beauty, a sensibility that Besler's work helped to cultivate.

Conclusion: A Gardener of Art and Science

Basilius Besler was more than just an apothecary or a botanist; he was a visionary who, with the crucial support of his patron and the skill of his collaborators, created an enduring monument to the plant kingdom. The `Hortus Eystettensis` is not merely a catalogue of plants; it is a celebration of their diversity and beauty, captured with a remarkable fusion of scientific precision and artistic elegance. It reflects the intellectual curiosity and aesthetic sensibilities of its time, a period when the boundaries between art and science were often fluid.

His work provided an invaluable record of the Eichstätt garden, a horticultural wonder lost to the ravages of war. More broadly, it contributed significantly to the development of botanical illustration, influencing how plants were studied, depicted, and appreciated for generations to come. Basilius Besler's legacy is etched in the exquisite lines of his engravings, a timeless testament to the enduring allure of the botanical world and the human drive to document its wonders. His contribution ensures his place among the great figures of botanical history and art.