Pierre-Joseph Redouté stands as a colossus in the specialized world of botanical art. Born during a time of burgeoning scientific inquiry and refined artistic taste, he navigated the tumultuous decades of French history, from the final years of the Ancien Régime through the Revolution, the Napoleonic Empire, and the Bourbon Restoration, leaving behind an unparalleled legacy of floral illustration. His work, characterized by its exquisite detail, scientific accuracy, and sheer aesthetic beauty, earned him the enduring moniker "The Raphael of Flowers," a testament to the perceived perfection and grace inherent in his depictions. Serving royalty and collaborating with leading botanists, Redouté transformed botanical illustration from a purely scientific record into a high art form, influencing generations of artists and delighting connoisseurs for over two centuries.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

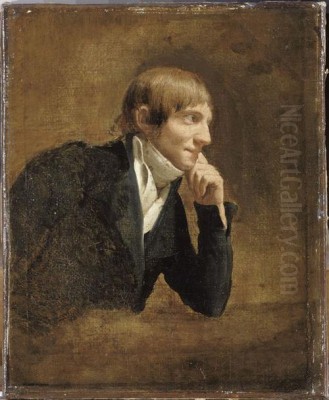

Pierre-Joseph Redouté was born on July 10, 1759, in Saint-Hubert, a town then in the Duchy of Luxembourg, part of the Austrian Netherlands (now in Belgium). Artistry ran deep in his family; both his father, Charles-Joseph Redouté, and his paternal grandfather were painters. The family was engaged in painting and decoration, providing young Pierre-Joseph with an early immersion in artistic practice, likely focused initially on decorative and perhaps religious themes common in provincial commissions.

This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured his innate talent, but Redouté's ambition extended beyond his hometown. At the young age of thirteen, he left Saint-Hubert to seek his fortune as an itinerant painter. For nearly a decade, he traveled, undertaking various commissions that included interior decoration, portraiture, and religious works. This period, though likely challenging, would have honed his technical skills and exposed him to a variety of styles and demands, building a foundation of versatility.

The lure of the French capital, the epicenter of European art and culture, proved irresistible. In 1782, Redouté made the pivotal move to Paris. There, he initially joined his elder brother, Antoine Ferdinand Redouté, who was finding work as a scenery designer for theatres. This theatrical work, demanding rapid execution and bold effects, contrasted sharply with the meticulous detail that would later define his botanical art, yet it added another dimension to his burgeoning experience within the Parisian artistic scene.

The Parisian Milieu and Key Influences

Paris in the 1780s was a city brimming with intellectual and artistic energy. For an aspiring artist with an interest in nature, the Jardin du Roi (Royal Garden), the precursor to the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, was an essential destination. Redouté began frequenting the gardens, drawn to the vast collection of plants and the community of artists and scientists working there. It was here that he encountered individuals who would decisively shape his career.

Among the most significant was the Dutch painter Gerard van Spaendonck (1746-1822). Van Spaendonck was already a celebrated master of flower painting, holding the prestigious position of Professor of Floral Painting at the Jardin du Roi. He recognized Redouté's talent and took him under his wing. Van Spaendonck was instrumental in teaching Redouté the refined techniques of watercolor painting on vellum, a medium perfectly suited for capturing the delicate textures and luminous colours of flowers. He also likely introduced Redouté to advanced printmaking techniques. Gerard's brother, Cornelis van Spaendonck (1756-1839), was also a noted painter of flowers and porcelain in Paris, contributing to the rich milieu of still-life artistry.

Another crucial figure was Charles Louis L'Héritier de Brutelle (1746-1800), a wealthy magistrate and passionate botanist. L'Héritier recognized the scientific potential in Redouté's artistic skill. He became a mentor and patron, providing Redouté with formal instruction in botany, emphasizing the importance of accurate floral dissection and morphological detail. L'Héritier granted Redouté access to his extensive personal library and herbarium, invaluable resources for the young artist. This collaboration grounded Redouté's art in rigorous scientific observation, setting him apart from purely decorative flower painters.

Through L'Héritier, Redouté began contributing illustrations to scientific publications. This early work honed his ability to translate precise botanical structures into elegant visual representations. The combination of Van Spaendonck's artistic guidance and L'Héritier's scientific mentorship was foundational, equipping Redouté with the unique blend of skills that would define his career. He was learning to see plants with the eye of both an artist and a scientist.

Mastering the Art of Botanical Illustration

Redouté's emerging style was a synthesis of the rich tradition of Dutch flower painting, exemplified by masters like Jan van Huysum (1682-1749) and Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) known for their detail and composition, and the precise requirements of scientific illustration as practiced by earlier botanical artists like Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708-1770). However, Redouté elevated this synthesis to a new level of refinement and elegance.

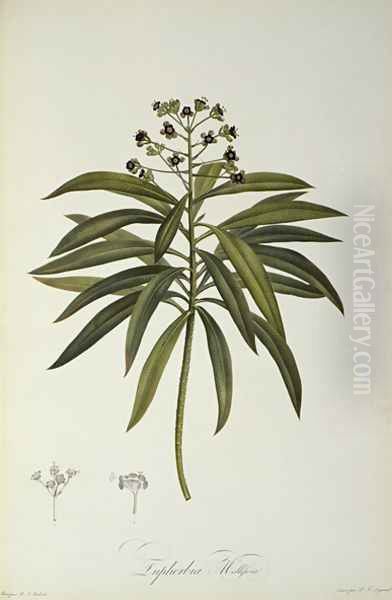

His medium of choice became watercolor on vellum. Vellum, prepared animal skin, provided a smooth, luminous surface that allowed for incredibly fine detail and subtle gradations of color. Redouté mastered a technique involving pure watercolor washes, layered delicately to achieve depth and translucency, capturing the very essence of petals, leaves, and stems. Unlike oil painting, watercolor on vellum offered a brilliance and clarity ideal for botanical subjects.

Crucially, Redouté was not merely copying the surface appearance of flowers. Guided by his botanical training, he depicted plants with remarkable accuracy, often including details of their structure, such as stamens, pistils, and seed pods. Yet, he imbued these scientific representations with an undeniable artistic grace. His compositions were balanced and elegant, isolating the subject against the stark white vellum page, focusing the viewer's attention entirely on the plant itself. There was often a lifelike quality, a sense of the flower freshly picked, sometimes with dew drops clinging to its petals.

This unique combination of scientific fidelity and aesthetic appeal made his work highly sought after. He managed to satisfy the rigorous demands of botanists while simultaneously captivating art lovers and wealthy patrons. His flowers were not just specimens; they were portraits of individual plants, capturing their unique character and beauty. This approach distinguished him from contemporaries who might lean more heavily towards either purely decorative arrangements or strictly diagrammatic scientific illustration.

Royal and Imperial Patronage

Redouté's exceptional talent quickly attracted the attention of the highest echelons of French society. His connection with L'Héritier likely facilitated introductions to the court. Before the revolution, he gained the patronage of Queen Marie Antoinette. He became one of her official drawing masters and was appointed Draughtsman and Painter to the Queen's Cabinet. This prestigious appointment provided him with financial stability and access to the royal gardens, further enhancing his opportunities to study and paint rare and beautiful plants. His association with the Queen, however, could have become perilous during the Reign of Terror, but Redouté managed to navigate the political upheavals.

The rise of Napoleon Bonaparte opened a new chapter of patronage. Empress Joséphine, Napoleon's first wife, was an avid and knowledgeable collector of plants, particularly roses. She established magnificent gardens at her estate, the Château de Malmaison, filling them with exotic species gathered from around the world. In 1798, Joséphine appointed Redouté as her official artist, tasking him with documenting the treasures of her gardens.

This period was perhaps the most fruitful of Redouté's career. Working amidst the splendors of Malmaison, he had access to an unparalleled collection of plants, including hundreds of varieties of roses and newly introduced species like lilies and amaryllis. This patronage directly led to some of his most famous publications, including the stunning Jardin de la Malmaison (1803-1804) and the multi-volume Les Liliacées (The Lilies) (1802-1816). He captured the ephemeral beauty of Joséphine's collection with unmatched skill.

Even after Joséphine's divorce from Napoleon and subsequent death, Redouté continued to enjoy imperial favor. He also served Empress Marie-Louise, Napoleon's second wife. His ability to maintain patronage across vastly different political regimes – from Bourbon monarchy to Napoleonic Empire and later, the restored Bourbon monarchy – speaks volumes about the universal appeal of his art and perhaps his diplomatic skills. He was appointed Drawing Master to the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in 1822, solidifying his official standing in the scientific and artistic community of Paris. Other artists, like Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744-1818), also navigated these turbulent times, finding patronage where they could, but Redouté's focus on botanical art gave him a unique niche.

The Magnum Opus: Les Roses

While Les Liliacées and Jardin de la Malmaison were monumental achievements, Redouté's name is perhaps most indelibly linked with roses. His magnum opus, Les Roses, published in installments between 1817 and 1824, remains one of the most famous and beloved botanical books ever created. This project was undertaken after the death of Empress Joséphine, whose passion for roses had undoubtedly inspired it.

The work was a collaboration with the botanist Claude-Antoine Thory (1757-1827), who provided the detailed botanical descriptions that accompanied each illustration. Thory's text ensured the scientific value of the publication, while Redouté's plates provided the visual splendor. Les Roses was published in folio size, featuring 170 exquisite plates depicting varieties of roses known in French gardens at the time, many sourced from Malmaison but also from other collections.

Each plate in Les Roses is a masterpiece of Redouté's mature style. He captured the delicate structure of the petals, the subtle variations in color, the thorns, leaves, and buds with breathtaking precision and artistry. The roses appear lifelike, rendered with a softness and luminosity achieved through his masterful watercolor technique and the subsequent printing process. The work documented not only established European varieties but also newly introduced cultivars from China, contributing significantly to the "rosomanie" or rose craze sweeping Europe.

Published in 30 installments (livraisons), Les Roses was an expensive and ambitious undertaking, aimed at a wealthy clientele of aristocrats, botanists, and bibliophiles. It cemented Redouté's reputation internationally as the preeminent painter of flowers. The images from Les Roses have been reproduced countless times since, becoming iconic representations of the flower they celebrate. The work stands as a perfect fusion of art, science, and horticultural passion.

Other Major Publications

Beyond the roses, Redouté's output was prolific. Les Liliacées (The Lilies), published between 1802 and 1816, is another monumental work, comprising eight folio volumes and nearly 500 plates. Despite its title, the work encompassed a broader range of plants belonging to the lily family and related groups, including tulips, irises, amaryllis, and orchids, many drawn from the Malmaison collection. The plates were executed using the same meticulous watercolor technique and stipple engraving process as his other major works, showcasing a stunning diversity of form and color. Botanists like Augustin Pyramus de Candolle contributed to the text.

Following the success of Les Roses, Redouté published Choix des plus belles Fleurs et des plus beaux Fruits (Selection of the Most Beautiful Flowers and Fruits) between 1827 and 1833. This work featured 144 plates and demonstrated his skill extended beyond flowers to include luscious depictions of fruits like peaches, plums, and grapes. While perhaps less famous than Les Roses or Les Liliacées, it further showcased his versatility and keen eye for natural beauty, appealing to a broad audience interested in horticulture and decorative arts.

Throughout his career, Redouté also contributed illustrations to numerous other botanical texts by prominent scientists of the day, including works by René Louiche Desfontaines and the aforementioned Augustin Pyramus de Candolle. His consistent ability to produce high-quality, accurate, and beautiful illustrations made him the go-to artist for major botanical publications originating in France during this period. These works collectively form an invaluable record of the plant world as understood and cultivated in the early 19th century.

Technical Innovations: Stipple Engraving

A significant part of Redouté's success and the distinctive quality of his published works lay in his mastery and refinement of the stipple engraving technique, known in French as gravure au pointillé. While not the inventor of the technique – it had been popularized in England by artists like Francesco Bartolozzi (1727-1815) – Redouté adapted and perfected it for botanical illustration, overseeing the printing process with great care.

Stipple engraving involves creating an image on a copper plate using dots and short flicks etched or engraved into the metal, rather than lines. The density and size of the dots determine the tonal values. This method allows for soft, subtle gradations of tone that are particularly well-suited for rendering the delicate curves and textures of flower petals and leaves, mimicking the effect of watercolor washes more effectively than traditional line engraving or mezzotint.

Redouté took this technique a step further by employing color printing. His plates were typically inked 'à la poupée' – a complex process where different colored inks were carefully applied to a single engraved plate using small pads (dollies or poupées) before each impression was pulled. Sometimes, multiple plates were used for different colors. This allowed for the prints to be issued with color already applied, rather than being hand-colored after printing, ensuring greater consistency and subtlety, although some hand-finishing might still have been employed.

This meticulous combination of stipple engraving and color printing, executed under Redouté's direct supervision, resulted in prints of exceptional quality and delicacy, faithfully translating the nuances of his original watercolors. It was a labor-intensive and costly process, contributing to the high price of his publications, but it set a new standard for botanical illustration and was crucial to the aesthetic success of works like Les Roses and Les Liliacées.

Redouté's Studio and Pupils

As his fame grew, Redouté became a sought-after teacher. He maintained a studio where he instructed aspiring artists, particularly women from aristocratic or affluent backgrounds for whom flower painting was considered a suitable accomplishment. His role as drawing master at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle also involved teaching.

Several pupils went on to become accomplished botanical artists in their own right, carrying forward his style and techniques. Among the most notable were Pancrace Bessa (1772-1846), who collaborated with Redouté and also enjoyed considerable success, contributing to major botanical publications like L'Herbier Général de l'Amateur. Henriette Vincent (1786-1834) was another talented pupil whose work clearly shows Redouté's influence.

Pierre Jean François Turpin (1775-1840) and Pierre-Antoine Poiteau (1766-1854) were also closely associated with Redouté, although they developed their own distinct and highly respected styles, often focusing on tropical flora and fruits. They collaborated on significant works and were major figures in French botanical illustration. The legacy of Redouté was thus disseminated not only through his published works but also through the artists he trained and influenced. His studio became a center for the continuation of the high standard he had set in botanical art.

Later Years and Legacy

Despite his fame and connections, Redouté's later years were marked by financial difficulties. The lavish folio publications were expensive to produce, and changes in patronage and the economic climate after the Napoleonic era impacted his income. He continued to teach and work, receiving the Legion of Honour in 1825, but reportedly faced hardship towards the end of his life.

Pierre-Joseph Redouté died suddenly in Paris on June 19, 1840, apparently while examining a lily. He was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery. His wife, Marie-Marthe Gobert, whom he had married in 1786 and with whom he had two sons, survived him and managed his remaining works.

Redouté's legacy, however, was secure. He left behind over 2,100 published plates depicting over 1,800 different species, the vast majority of which had never been illustrated before. His work represents a unique confluence of art and science during a golden age of botanical exploration and illustration. His influence extended far beyond the scientific community. His elegant floral depictions became immensely popular for decorative purposes, reproduced on porcelain, textiles, wallpaper, and prints, shaping aesthetic tastes for generations.

Compared to the highly detailed, sometimes dramatic, botanical plates of contemporaries like the Austrian Bauer brothers (Franz and Ferdinand Bauer) working at Kew Gardens, or the ambitious, almost theatrical compositions in Dr. Robert John Thornton's Temple of Flora (published in Britain around the same time), Redouté's work strikes a unique balance between accuracy, elegance, and accessibility. While English contemporaries like James Sowerby (1757-1822) produced vast quantities of scientifically valuable illustrations, Redouté's work achieved a level of artistic refinement that remains unsurpassed.

Today, original editions of Redouté's books are highly prized collector's items, and his original watercolors are held in major museums and botanical institutions worldwide. His images continue to be reproduced globally, testament to the enduring appeal of his vision. He remains the undisputed master of French botanical illustration, the "Raphael of Flowers" whose work continues to inspire awe and admiration.

Conclusion

Pierre-Joseph Redouté navigated the complex social and political landscape of late 18th and early 19th century France to become the era's preeminent botanical artist. His unique ability to blend meticulous scientific accuracy with sublime artistic grace set his work apart. Through masterpieces like Les Liliacées and the iconic Les Roses, fueled by prestigious patronage from figures like Queen Marie Antoinette and Empress Joséphine, and enabled by his mastery of watercolor and innovative stipple engraving techniques, he created an enduring legacy. More than just illustrations, his works are portraits of plants, capturing their essence with unparalleled elegance. His influence permeated not only botany and art history but also the decorative arts, ensuring that the beauty he captured continues to enrich lives centuries later. Pierre-Joseph Redouté remains a benchmark against which botanical art is measured, a true master whose dedication to the beauty of the natural world left an indelible mark on art history.