Georg Dionysius Ehret stands as a colossus in the history of botanical art. Active during the vibrant intellectual ferment of the 18th century Enlightenment, he forged an unparalleled path, merging meticulous scientific observation with breathtaking artistic execution. Born in Germany, his journey took him across Europe, culminating in a celebrated career in England where he became the most sought-after botanical painter of his time. His work not only documented the burgeoning understanding of the plant kingdom, driven by figures like Carl Linnaeus, but also set an aesthetic standard that defined the "Golden Age of Botanical Art" and continues to inspire awe today. This exploration delves into the life, technique, collaborations, and enduring legacy of a man whose passion for plants translated into timeless masterpieces.

From Gardener's Son to Aspiring Artist

Georg Dionysius Ehret entered the world on January 30, 1708, in Heidelberg, Germany. His origins were humble yet deeply connected to the world he would later depict with such mastery. His father was a market gardener, providing young Georg with an early, intimate exposure to the plant world. This foundational knowledge, combined with an innate talent for drawing, set the stage for his future career. He received some initial training in drawing, a skill that quickly became apparent.

Following his early education, Ehret pursued the practical path laid out by his family background, becoming a gardener's apprentice. His skill and dedication saw him rise through the ranks. However, his artistic talents could not be contained within the confines of horticulture alone. His ability to capture the likeness of plants with accuracy and flair drew attention, leading him towards the specialized field of botanical illustration. This transition marked the beginning of a journey that would elevate him from a skilled craftsman to an artist of international renown.

Early Career and the Weinmann Experience

Ehret's professional journey as an illustrator began in Regensburg, where he found employment with the apothecary and botanist Johann Wilhelm Weinmann around 1730. Weinmann was compiling a monumental botanical work, the Phytanthoza Iconographica, an ambitious project aiming to illustrate thousands of plants. Ehret was commissioned to produce illustrations for this publication, a task that showcased his burgeoning skills. His detailed and vibrant depictions were a significant contribution to the early stages of this massive undertaking.

However, this formative experience was marred by conflict. Ehret felt exploited, believing his compensation was inadequate for the quality and quantity of work demanded. Sources suggest he contributed around 500 plates before the relationship soured. Feeling undervalued, Ehret made the difficult decision to leave Weinmann's employ. This act of self-assertion, though risky, proved pivotal. It freed him to seek opportunities elsewhere, setting him on a path of travel and collaboration that would ultimately define his career and lead him to greater recognition and fairer patronage. The Phytanthoza Iconographica was eventually completed with contributions from other artists, but Ehret's early involvement remains a notable, if complex, chapter in his story.

Journeyman Years: Travel and Development

Leaving Regensburg, Ehret embarked on a period of travel that broadened his horizons and artistic connections. He journeyed through Europe, visiting key centers of learning and botanical interest. His travels took him to Basel, Switzerland, a city with a strong tradition in botany and printing, where he likely honed his skills and made valuable contacts. He also spent time in France, visiting Paris, another hub of scientific and artistic activity during the Enlightenment.

These travels were not merely geographical; they represented a crucial phase of artistic and intellectual development. Ehret observed different styles, encountered new plant species in various gardens and collections, and interacted with other artists and scientists. This period allowed him to absorb diverse influences and refine his unique approach, blending the precision demanded by science with the aesthetic sensibilities gaining traction in the art world. It was during these journeyman years that he laid the groundwork for the international network of patrons and collaborators that would support his later career.

The Dutch Nexus: Linnaeus, Clifford, and the Hortus Cliffortianus

A defining moment in Ehret's career occurred in the Netherlands around 1735-1736. Here, he encountered two figures who would profoundly shape his work and reputation: the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus and the wealthy Anglo-Dutch banker and plant enthusiast George Clifford III. Clifford maintained a magnificent garden and herbarium at his estate, Hartekamp, near Haarlem, filled with exotic species sourced through his connections with the Dutch East India Company.

Clifford commissioned Linnaeus, then working in the Netherlands, to catalogue his extensive collection. He also employed Ehret to illustrate the most remarkable specimens. This collaboration resulted in the Hortus Cliffortianus, published in 1738. It was a landmark publication, not only for its botanical content but also for its exquisite illustrations. Ehret produced the detailed plates, engraved primarily by Jan Wandelaar, which visually complemented Linnaeus's descriptions and newly developing system of plant classification.

Working closely with Linnaeus was particularly influential. Linnaeus emphasized the importance of accurately depicting the reproductive parts of flowers (stamens and pistils), which formed the basis of his revolutionary sexual system of classification. Ehret absorbed this lesson, incorporating meticulous details of floral structures into his work, thereby enhancing its scientific value immensely. The Hortus Cliffortianus established Ehret's reputation as a premier botanical artist capable of meeting the rigorous demands of the new scientific botany.

Settling in England: A Hub of Patronage and Opportunity

Around 1736, after his fruitful period in the Netherlands, Ehret moved to England, primarily settling in London. This move proved decisive for his career. England, with its burgeoning empire, wealthy aristocracy interested in science and horticulture, and established institutions like the Royal Society and the Chelsea Physic Garden, offered unparalleled opportunities for a botanical artist of his caliber.

Ehret quickly attracted the attention and support of prominent figures. Sir Hans Sloane, the physician and collector whose vast holdings would form the basis of the British Museum, became an important early patron. Dr. Richard Mead, another influential physician and collector, also supported his work. Perhaps most significantly, he gained the patronage of Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, the Duchess of Portland, a passionate naturalist and collector with extensive gardens and collections. These patrons commissioned works, purchased his paintings, and facilitated connections within London's scientific and social elite.

His connection with the Chelsea Physic Garden was also crucial. Established by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, it was a leading center for botanical study and plant introduction. Ehret worked closely with Philip Miller, the garden's renowned curator and author of the widely successful Gardener's Dictionary. Ehret provided illustrations for Miller's publications and painted many of the plants cultivated at Chelsea, further solidifying his position at the heart of British botanical activity. England became his permanent home, where he lived and worked until his death in 1770.

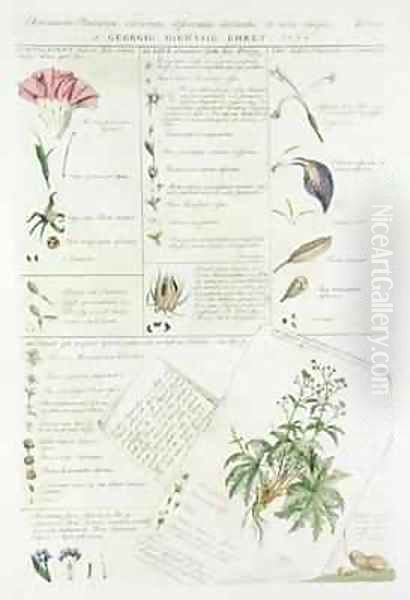

The Ehret Style: Science Meets Rococo Elegance

Georg Dionysius Ehret's artistic style is celebrated for its remarkable synthesis of scientific accuracy and aesthetic grace. His training as a gardener gave him an intimate understanding of plant structure and growth, while his artistic talent allowed him to translate this knowledge into visually compelling images. He worked primarily in watercolor and gouache (bodycolor) on paper or vellum, mediums that allowed for both precise detail and vibrant coloration.

Influenced by Linnaeus, Ehret paid scrupulous attention to botanical detail, accurately rendering the forms of leaves, petals, stems, and, crucially, the reproductive organs essential for classification. His depictions were so precise that they could often be used for scientific identification. Yet, his work transcends mere scientific documentation. There is an undeniable artistic sensibility, often reflecting the prevailing Rococo style with its emphasis on elegance, dynamic curves, and decorative appeal. His compositions are often lively, capturing the plant not as a static specimen but as a living entity, sometimes showing different stages of its life cycle – bud, flower, and fruit – within a single plate.

Compared to predecessors like Maria Sibylla Merian, whose work often integrated insects and had a slightly different narrative quality, or contemporaries like the Dutch flower painter Jacob van Huysum, whose focus was more purely decorative, Ehret struck a unique balance. His paintings possess a clarity and scientific integrity that set a new standard for botanical illustration, while retaining an artistic vitality and beauty that appealed to collectors and connoisseurs. He truly defined the visual language of botany in his era.

Mastering the Medium: Watercolor and Vellum

Ehret's technical mastery, particularly with watercolor and gouache on vellum, was central to his success. Vellum, a fine parchment prepared from animal skin, provided a smooth, luminous surface that was ideal for capturing the delicate textures and vibrant colors of plants. Its durability also ensured the longevity of his works, many of which survive in remarkable condition today.

He employed watercolor with exceptional skill, layering transparent washes to build up form and depth, capturing the subtle gradations of color in petals and leaves. He often combined this with gouache, an opaque watercolor, to add highlights, fine details, or richer, more solid blocks of color. This combination allowed him to achieve both delicacy and intensity. His linework was precise yet fluid, defining structures clearly without sacrificing naturalism.

The quality of his original paintings on vellum was widely recognized as superior. While many of his works were translated into engravings for publication – often skillfully executed by engravers like Johannes Jacobus Haid and his son Johannes Elias Haid for Plantae Selectae, or Jan Wandelaar for Hortus Cliffortianus – the process inevitably involved some loss of nuance compared to the originals. The hand-coloring of these prints, while often beautifully done, could not fully replicate the subtlety and luminosity of Ehret's own hand. His original works remain the ultimate testament to his technical brilliance.

Masterworks of Botanical Illustration: Key Publications

Ehret's reputation rests significantly on his contributions to several major botanical publications of the 18th century, alongside his numerous individual paintings.

Hortus Cliffortianus (1738): As previously mentioned, this collaboration with Linnaeus and Clifford was a landmark achievement. Ehret's plates provided the visual evidence for Linnaeus's descriptions, beautifully illustrating the wealth of Clifford's garden at Hartekamp. It cemented his reputation early in his career.

Plantae Selectae (1750-1773): Perhaps his most famous published work, this collection of 100 plates was produced in collaboration with the Nuremberg physician and botanist Christoph Jakob Trew, who wrote the descriptions. Ehret provided the stunning original paintings, which were then engraved and hand-colored, primarily by Johann Jacob Haid and his son Johann Elias Haid in Augsburg. Published in installments, Plantae Selectae showcased rare and exotic plants from around the world, depicted with Ehret's characteristic blend of accuracy and artistry. It remains one of the most beautiful botanical books ever produced.

Plantae et Papiliones Rariores (1748-1759): This smaller, rarer work focused on select plants and butterflies, demonstrating his skill extended beyond flora. Published in London in parts, it further highlighted his ability to capture the beauty of the natural world in exquisite detail.

Contributions to Other Works: Ehret also provided illustrations for other significant publications. He contributed plates to later editions of Mark Catesby's pioneering The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. He illustrated Patrick Browne's The Civil and Natural History of Jamaica (1756). His illustrations also appeared in Philip Miller's Figures of the Most Beautiful, Useful, and Uncommon Plants Described in the Gardener's Dictionary (1755-1760). His illustration explaining the Linnaean sexual system, published in 1736, was also highly influential in disseminating the new classification method visually.

Individual Masterpieces: Beyond published works, Ehret created numerous individual paintings, often on commission. Famous examples include his stunning depictions of Magnolia grandiflora, the Iris variegata (1764), and the Helleborus niger (Christmas Rose), showcasing his ability to capture the unique character and beauty of each species. His depiction of Acer species, like Acer III, also demonstrates his skill with trees.

Collaboration, Competition, and Patronage

Ehret's career exemplifies the complex interplay of collaboration, competition, and patronage that characterized the scientific and artistic worlds of the 18th century. His most fruitful collaborations were with scientists and patrons who recognized and respected his talent. The partnerships with Linnaeus, Clifford, and Trew were mutually beneficial, advancing both science and art. Linnaeus provided the systematic framework, Clifford and Trew the financial backing and access to specimens, and Ehret the visual realization that brought their work to life.

His relationships with patrons in England, such as Sir Hans Sloane, Dr. Richard Mead, and the Duchess of Portland, were crucial for his financial stability and social standing. These wealthy individuals not only commissioned and purchased his work but also provided access to rare plants from their gardens and collections, fueling his artistic output. His long association with Philip Miller at the Chelsea Physic Garden provided a steady stream of subjects and ensured his work was tied to one of the most important botanical institutions of the day.

However, his early experience with Johann Wilhelm Weinmann serves as a reminder of the potential for exploitation. Artists, even highly skilled ones, often occupied a precarious position, dependent on the goodwill and fairness of their employers or patrons. Ehret's decision to leave Weinmann demonstrates his awareness of his own worth. While direct competition with other botanical artists like Jacob van Huysum existed, Ehret's unique blend of scientific rigor and artistic flair, coupled with his strong network, arguably placed him at the pinnacle of his field during his lifetime. His ability to navigate these complex relationships was as important to his success as his artistic talent.

Teaching and Transmitting Knowledge

Beyond his own prolific output, Georg Dionysius Ehret played a significant role as an educator, transmitting his skills and passion for botanical art to others. After settling in London, he established himself as a sought-after drawing master. He offered lessons in botanical painting, attracting pupils from affluent backgrounds, including many aristocratic women for whom botanical drawing was considered a suitable and fashionable accomplishment.

His teaching activities were important for several reasons. Firstly, they provided a supplementary source of income. Secondly, they helped to disseminate his style and techniques, influencing the next generation of botanical artists and illustrators in Britain. By instructing members of the gentry and aristocracy, he also helped to foster a wider appreciation for botanical art and science within influential circles. Figures like the Duchess of Portland were not just patrons but also keen students of natural history, and Ehret's guidance likely enhanced their understanding and engagement.

While the names of many specific pupils may not be widely recorded, his influence can be seen in the general flourishing of botanical art in Britain in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He helped establish a tradition of detailed, accurate, yet aesthetically pleasing plant illustration that would be carried forward by artists who followed, even if their styles evolved, such as the later, highly celebrated Pierre-Joseph Redouté in France, known for his stipple engravings of roses and lilies. Ehret's role as a teacher solidified his central position in the botanical art world of his time.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Georg Dionysius Ehret died in London on September 9, 1770, leaving behind an immense legacy that continues to resonate in the worlds of art and science. He is universally regarded as one of the greatest botanical artists of all time, a key figure who defined the genre during its "Golden Age." His ability to seamlessly integrate scientific precision with artistic beauty set a standard that few have matched.

His influence was immediate and lasting. His works were essential tools for botanists in the era of Linnaean classification, providing clear visual references that aided identification and understanding. Botanists like Sir Joseph Banks, who sailed with Captain Cook and later became President of the Royal Society, highly valued accurate botanical illustrations and amassed significant collections, including works potentially influenced by Ehret's standards. The plant genus Ehretia (in the Borage family, Boraginaceae) was named in his honor by Patrick Browne, a testament to his standing within the scientific community.

Today, Ehret's original paintings and the books he illustrated are treasured artifacts. Major collections are held in institutions like the Natural History Museum in London, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Royal Society, and internationally at the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation in Pittsburgh, which has held exhibitions dedicated to his work. His art continues to be studied, admired, and reproduced, captivating audiences with its timeless elegance and scientific integrity. He remains a pivotal figure, demonstrating the powerful synergy possible between artistic vision and scientific inquiry. His work serves as a benchmark against which botanical art is often measured.

Conclusion: An Unsurpassed Vision

Georg Dionysius Ehret's life journey, from a gardener's son in Heidelberg to the most celebrated botanical artist in London, is a remarkable story of talent, dedication, and strategic navigation of the 18th-century world. His collaboration with giants like Linnaeus, his service to patrons like Clifford and Trew, and his decades of meticulous work established a new paradigm for botanical illustration. He captured the explosion of botanical discovery during the Age of Enlightenment, depicting plants from Europe, the Americas, and beyond with unparalleled skill.

His legacy is multi-faceted: scientifically invaluable illustrations that aided the classification and understanding of plants; artistically brilliant works that exemplify the elegance of the Rococo while adhering to scientific truth; and an enduring influence on subsequent generations of artists and the appreciation of botanical beauty. Ehret demonstrated that art and science need not be separate pursuits but could enrich each other, producing results that are both informative and profoundly beautiful. His paintings remain vibrant testaments to the wonders of the plant kingdom and the exceptional vision of the artist who depicted them.