Benedetto Luti stands as a pivotal figure in the transition of Roman art from the grandeur of the High Baroque towards the more refined sensibilities of the Late Baroque and early Rococo. Born in Florence on November 17, 1666, he moved to Rome, where he established himself as one of the city's most sought-after artists in the early decades of the 18th century. Luti was not only a highly skilled painter in both oil and pastel but also an influential teacher, a respected collector, and a savvy art dealer, weaving himself into the fabric of Roman artistic and social life until his death on June 17, 1724.

Florentine Foundations and Early Training

Benedetto Luti's artistic journey began in Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance, a city steeped in artistic tradition. He was born into a craftsman's family, suggesting an early exposure to artisanal skills. His formal training came under the guidance of Antonio Domenico Gabbiani (1652-1726), a prominent Florentine painter known for his portraits and large-scale decorative works. Gabbiani's instruction would have provided Luti with a solid grounding in Florentine disegno – the emphasis on drawing and clear composition – which remained a subtle underpinning throughout his career, even as he embraced the more painterly qualities of the Roman Baroque.

The artistic environment of late 17th-century Florence, while perhaps lacking the dynamic energy of Rome, still offered exposure to the works of earlier masters and contemporary trends. Luti absorbed these influences, developing technical proficiency and an understanding of composition and colour that would serve him well. However, the true centre of artistic innovation and patronage in Italy at this time was Rome, and it was inevitable that an ambitious young artist like Luti would gravitate towards the Eternal City.

Arrival in Rome and Baroque Influences

Luti moved to Rome in 1691, drawn by the opportunities for patronage and the vibrant artistic milieu. His arrival was facilitated by the support of Cosimo III de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, a significant patron of the arts who maintained connections with artists working in Rome. This patronage provided Luti with crucial initial support and introductions, allowing him to begin establishing his reputation in a competitive environment.

Once in Rome, Luti immersed himself in the dominant artistic currents. He was profoundly influenced by the legacy of the High Baroque, particularly the work of Pietro da Cortona (1596-1669), whose dynamic compositions and rich colourism had defined an era of Roman painting. Equally important was the influence of Carlo Maratti (1625-1713), the leading painter in Rome during the later 17th century. Maratti represented a more classicizing trend within the Baroque, tempering its exuberance with a Raphaelesque grace and clarity. Luti skillfully synthesized these influences, blending Cortona's energy with Maratti's refined classicism.

His style evolved to embrace the key characteristics of the Late Roman Baroque: a sophisticated use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create drama and volume, a rich and often warm palette, and a focus on conveying emotion and psychological depth in his figures. He demonstrated a mastery of anatomy, composition, and expression, grounding his Baroque dynamism in sound classical principles learned partly from his Florentine background and reinforced by the Maratti school in Rome.

Mastery in Oil Painting

Luti excelled in oil painting, the traditional medium for large-scale commissions and easel paintings. His works in oil often tackled religious and mythological subjects, showcasing his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and dramatic narratives. He received significant commissions, contributing to the decoration of important Roman churches, a mark of high status for any painter of the era. For instance, he painted a prophet, Isaiah, for the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, placing him alongside other prominent artists working on Pope Clement XI's major refurbishment project.

His oil paintings are characterized by their strong compositions, often employing dynamic diagonals and swirling movement typical of the Baroque. However, compared to the High Baroque intensity of artists like Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Baciccio), Luti's work often exhibits a slightly softer, more graceful quality, hinting at the emerging Rococo aesthetic. His colour palettes could be rich and vibrant, but also capable of subtle harmonies, and his handling of light was consistently skillful, used to highlight key figures and enhance the emotional impact of the scene.

Works like Christ and the Samaritan Woman (c. 1715-1720) exemplify his approach in oil. The interaction between the figures is rendered with psychological sensitivity, the drapery is handled with fluidity, and the landscape setting is atmospheric. The composition is balanced, drawing the viewer's eye to the central exchange, while the use of light and colour creates a warm, engaging scene that combines narrative clarity with painterly appeal. He successfully navigated the demands of patrons who expected works that were both doctrinally sound and aesthetically pleasing.

Pioneer of the Pastel Portrait

While accomplished in oils, Benedetto Luti achieved particular renown for his work in pastels. He was one of the earliest Italian artists, and certainly one of the most prominent in Rome, to embrace pastels not just for preparatory sketches but as a medium for finished works, particularly portraits and head studies. This was a significant development, as pastels offered a unique immediacy, luminosity, and softness that differed markedly from the more laborious process of oil painting.

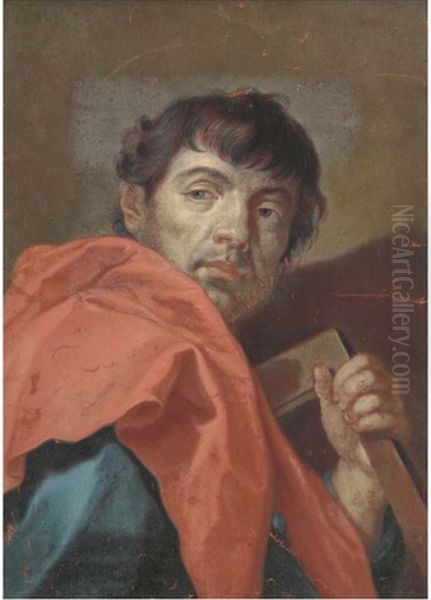

Luti's pastels are celebrated for their delicate handling, vibrant yet subtle colouring, and remarkable ability to capture textures, especially skin tones and fabrics. He often worked on paper, using the texture of the support to enhance the powdery quality of the medium. His subjects included formal portraits, intimate studies of children and angels, and character studies, often featuring bearded men or figures drawn from religious narratives. He demonstrated an exceptional sensitivity to the medium's potential for capturing fleeting expressions and a sense of lifelike presence.

His Study of a Girl in a Red Dress (1717) and Young Boy with a Flute (1717) are exquisite examples of his pastel technique. They showcase his ability to model form softly, using subtle gradations of tone and colour, and to infuse the subjects with a gentle charm. The Study of a Boy in a Blue Jacket (1717) similarly highlights his mastery of colour harmony and his sympathetic portrayal of youth. These works possess a freshness and intimacy that contributed significantly to the growing popularity of pastel across Europe in the 18th century.

Luti's success in pastels placed him in dialogue with other emerging specialists, most notably the Venetian artist Rosalba Carriera (1675-1757), who would become the undisputed European master of the pastel portrait shortly after Luti's peak. While Carriera's style often had a lighter, more overtly Rococo touch, Luti's pastels retained a connection to Baroque structure and psychological depth, even in their delicacy. His work in this medium was highly sought after by collectors and significantly influenced subsequent artists exploring its possibilities.

Major Works and Prestigious Commissions

Throughout his career in Rome, Luti produced a significant body of work that cemented his reputation. One of his early notable successes was God Cursing Cain after the Murder of Abel (using red, black, and white chalk, related oil version likely existed), exhibited possibly around 1692. This work, praised for its dramatic intensity and skillful draughtsmanship, helped establish him among the leading artists in Rome. Its dynamic composition and emotional force are characteristic of his engagement with powerful religious themes.

His religious paintings continued to be in demand. Besides the Isaiah for San Giovanni in Laterano, he executed works for other churches and private chapels. His ability to depict sacred figures with both dignity and relatable humanity appealed to the religious sensibilities of the time. Works like Saint John the Evangelist (1712, likely a pastel study related to a larger commission) show his capacity for conveying spiritual intensity through portraiture.

Luti also received commissions for mythological subjects, such as the Diana and Actaeon mentioned as being produced by his workshop, indicating he likely oversaw assistants in producing decorative schemes. These works allowed for a display of classical learning and the depiction of the human form in dynamic poses, appealing to the tastes of aristocratic patrons decorating their palaces.

His patrons included some of the most powerful families in Rome, such as the Colonna, Pallavicini, Barberini, and Odescalchi. Furthermore, he enjoyed Papal favour, working under Clement XI (Pope 1700-1721) and receiving recognition from subsequent pontiffs like Clement XII (Pope 1730-1740, though Luti died before his papacy began, indicating perhaps earlier patronage or continued esteem for his work). This high level of patronage underscores his central position in the Roman art world. His works were not confined to Italy; they were collected by connoisseurs in England, France, and Germany, reflecting his international reputation.

Teacher and Mentor

Beyond his own artistic production, Benedetto Luti played a crucial role as an educator. He ran a busy studio and offered private lessons, attracting pupils from Italy and abroad between roughly 1710 and 1720. His reputation as both a master technician and a successful artist made him a desirable teacher for aspiring painters seeking to learn the Roman style.

Among his notable students were several artists who went on to achieve considerable success. These included Pietro Bianchi (1694-1740), known for his religious and historical paintings; Placido Costanzi (1702-1759), who became a leading painter in Rome in the generation after Luti; and Giovanni Domenico Piastrini (1678-1740).

Luti also taught foreign artists undertaking the Grand Tour or seeking training in Rome. Prominent among these were the English artist and architect William Kent (c. 1685-1748), who studied painting with Luti before turning primarily to architecture and design, and the French brothers Jean-Baptiste van Loo (1684-1745) and Carle Van Loo (1705-1765), both of whom became highly successful painters in France. The presence of these international students highlights Rome's, and Luti's, importance as a centre for artistic education. It's also plausible that Giovanni Battista Vanvitelli (1700-1773), later famous as an architect, received some early painting instruction or influence from Luti's circle.

Luti's teaching likely emphasized the principles he himself followed: a strong foundation in drawing, a mastery of colour and light, an understanding of classical composition, and the ability to convey emotion effectively. He passed on the lineage of the Roman Late Baroque, influencing the style of artists who would dominate the scene in the mid-18th century, such as Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787), who, while not a direct pupil, certainly absorbed lessons from Luti's refined classicism and portraiture.

Collector and Art Dealer

Complementing his roles as painter and teacher, Benedetto Luti was an active and highly regarded art collector and dealer. This was not uncommon for successful artists of the period, but Luti seems to have pursued these activities with particular acumen. He operated a successful school and likely used his studio and connections to facilitate the sale of artworks, both his own and those of other artists, past and present.

He amassed a significant personal collection, particularly of drawings. While the figure of 15,000 works mentioned in some sources might be an exaggeration or refer specifically to prints and drawings rather than paintings, there is no doubt his collection was substantial and respected. Collecting drawings was a mark of connoisseurship, providing study material for himself and his students, and serving as valuable assets. His collection likely included works by Italian masters from the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

His role as a dealer connected him with a wide network of patrons, fellow artists, and agents across Europe. His connections, particularly with the Tuscan court through Cosimo III's initial support, likely proved advantageous in marketing his works and potentially those he dealt in. This activity not only provided an additional source of income but also enhanced his status as a connoisseur and a central figure in the Roman art market. His expertise would have been sought after by collectors seeking to acquire works or authenticate them.

Academician and Social Standing

Luti's success and reputation earned him a prominent place within Rome's official artistic institutions. He became a member of the prestigious Accademia di San Luca, the city's academy of artists. Membership signified peer recognition and conferred considerable status. His standing within the Academy grew over the years, culminating in his election as Principe (President or Director) in 1720. This was the highest honour the Academy could bestow, reflecting the deep respect he commanded among his fellow artists.

His role as Principe involved administrative duties and ceremonial functions, further solidifying his position at the apex of the Roman art world. It placed him in direct contact with the highest levels of ecclesiastical and aristocratic patronage. His patrons already included Popes and leading noble families, and his circle extended to influential cardinals and visiting dignitaries.

He was known to have connections with the exiled Stuart court in Rome, particularly James Francis Edward Stuart (the "Old Pretender"), son of the deposed King James II of England. Painting portraits or other works for such figures, even if politically sensitive, demonstrated the breadth of his connections. Luti navigated the complex social and political landscape of Rome effectively, maintaining good relationships with diverse factions and patrons. His studio became a meeting place, a hub of artistic activity and connoisseurship.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Benedetto Luti remained active as an artist, teacher, and dealer until his death in Rome in 1724, at the age of 57. While details of his final years are relatively scarce compared to the documentation of his peak period, his influence was well-established. He left behind a significant body of work distributed in churches, palaces, and collections across Europe.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he represents a crucial link between the High Baroque classicism of Maratti and the emerging Rococo style. His work, particularly in pastel, anticipated the lighter palettes and more intimate sensibilities of the 18th century, while retaining a Baroque sense of structure and emotional depth. He demonstrated that pastel could be a medium for serious, finished artworks, paving the way for later specialists like Carriera and Maurice Quentin de La Tour.

As a teacher, he shaped a generation of artists, both Italian and foreign, transmitting the sophisticated Roman style of the early 18th century. His students carried his influence into various European artistic centres. Figures like William Kent, for example, played a key role in establishing Palladian architecture and related decorative styles in England, informed partly by his Italian training.

As a collector and dealer, he contributed to the appreciation and circulation of art, particularly drawings, and embodied the ideal of the artist-connoisseur. While some questions regarding attribution or later restoration occasionally arise concerning works associated with him or his studio – a common issue for prolific artists with workshops – his core oeuvre remains a testament to his skill and importance.

Benedetto Luti remains a key figure for understanding the evolution of Roman art in the early Settecento. He successfully blended Florentine disegno with Roman colore, absorbed the lessons of Cortona and Maratti, excelled in both oil and the newly fashionable pastel, and played a central role in the city's artistic life through teaching, dealing, and his leadership at the Accademia di San Luca. His refined, expressive, and technically brilliant work continues to be admired in museums and collections worldwide. He stands as a master whose career illuminates the rich artistic transitions of the Late Baroque era.