Elmer Wachtel stands as a significant, albeit sometimes quietly acknowledged, figure in the vibrant tapestry of early Californian Impressionism. His life, a fascinating journey from the concertmaster's chair to the sun-drenched canvases of the West, reflects a deep sensitivity to the nuances of his environment. Wachtel's artistic legacy is inextricably linked with the burgeoning art scene of Southern California in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period when artists sought to capture the unique light and diverse topography of the region. His work, characterized by its lyrical quality and atmospheric depth, offers a window into a California on the cusp of transformation, a landscape still largely untamed yet increasingly beloved by those who sought its beauty.

From Baltimore to the Golden State: An Unconventional Path

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, on January 21, 1864, Elmer Wachtel's early life gave little indication of his future as a prominent landscape painter. His family later relocated to Lanark, Illinois, where he spent his formative years. It was music, not painting, that initially captured his passion. A talented violinist, Wachtel was largely self-taught, a testament to his innate artistic drive and discipline. This musical inclination would, in many ways, subtly inform his later visual art, lending it a harmonious and rhythmic quality.

In 1882, at the age of eighteen, Wachtel made a pivotal move that would forever alter the course of his life. He traveled to San Gabriel, California, to live with his older brother, Howard Wachtel, who was managing the extensive ranch holdings of Leland Stanford. For the next decade, Elmer worked various jobs on the ranch, immersing himself in the agricultural life of Southern California. However, his musical talents did not lie dormant. He continued to practice the violin, and his skill eventually led him to Los Angeles.

A Musical Interlude: The Los Angeles Philharmonic

The burgeoning cultural scene of Los Angeles provided an outlet for Wachtel's musical abilities. He secured a position as the first violinist in the newly formed Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in 1888. For several years, music was his primary profession, and he earned a respectable living through performances and by giving violin lessons. This period was crucial, as it not only provided him with financial stability but also embedded him within the artistic community of the rapidly growing city.

Despite his success in music, a different artistic calling began to stir within him. The landscapes of Southern California, with their dramatic interplay of light and shadow, rugged mountains, and expansive coastlines, exerted a powerful pull. He began to dabble in drawing and painting, initially as a pastime, but the allure of visual expression grew steadily stronger. His early efforts were likely encouraged by the general artistic ferment in California, where painters like William Keith, known for his majestic and moody depictions of the California wilderness, were already establishing a regional artistic identity.

The Transition to Canvas: Formal Studies and Self-Discovery

By the early 1890s, Wachtel's desire to pursue painting more seriously led him to seek formal instruction. He briefly studied at the Art Students League in New York City around 1895. However, he found the academic methods restrictive and, characteristically independent, left after only a short period – some accounts say as little as two weeks. This dissatisfaction with conventional pedagogy suggests an artist already developing a strong personal vision, one that perhaps chafed under rigid academic structures.

His quest for artistic knowledge then led him across the Atlantic to London. He enrolled at the Lambeth School of Art, where he continued his studies. It was in London that he encountered Gutzon Borglum, the ambitious American sculptor who would later achieve monumental fame for carving Mount Rushmore. They were fellow students, sharing the experience of expatriate artists honing their craft in a European cultural capital. This period abroad, though not extensively documented in terms of specific teachers, undoubtedly broadened Wachtel's artistic horizons and exposed him to different traditions and contemporary movements. He also spent time in Hamburg, Germany, further enriching his European experience.

Upon his return to California, Wachtel was more committed than ever to his career as a painter. He established a studio in Los Angeles and began to dedicate himself fully to capturing the landscapes that had so captivated him. He also took some instruction from John Bond Francisco, a respected Los Angeles artist and musician, who, like Wachtel, had a background in music before turning to painting. Francisco was known for his Tonalist landscapes, and it's plausible that Wachtel absorbed some of this sensibility, particularly the emphasis on mood and atmosphere.

Marion Kavanagh: A Partnership in Art and Life

A defining moment in Elmer Wachtel's personal and professional life occurred in 1903. Marion Kavanagh, a talented young artist from Milwaukee, arrived in California. Kavanagh had studied at the Art Institute of Chicago under renowned American Impressionist William Merritt Chase and later with Frank DuMond. She had come west, partly on a commission from the Santa Fe Railroad to paint the landscapes along their routes, a common practice that helped popularize the imagery of the American West.

Upon arriving in San Francisco, Marion sought the advice of the venerable William Keith. Keith, recognizing her talent and perhaps sensing a kindred spirit, suggested she travel to Los Angeles and seek out Elmer Wachtel for further instruction or collaboration. The meeting proved serendipitous. Elmer and Marion quickly found common ground, both in their artistic aspirations and their personal affections. They were married in Chicago in 1904, embarking on a partnership that would last for a quarter of a century.

Marion Kavanagh Wachtel was a formidable artist in her own right, often favoring watercolors, while Elmer predominantly worked in oils. Their artistic styles, though distinct, were complementary. They frequently embarked on sketching and painting expeditions together, traveling by horse and buggy, and later by automobile, to remote areas of Southern California and the Southwest. They built a home and studio in the Arroyo Seco area of Pasadena, a picturesque canyon that was a haven for artists, including figures like Guy Rose, a leading California Impressionist who had studied with Monet at Giverny, and Benjamin Chambers Brown, known for his vibrant poppy fields and Sierra landscapes.

Their collaborative spirit was such that they often worked on similar subjects, each interpreting the scene through their preferred medium and individual sensibility. Marion's decision to adopt "Wachtel" as her professional surname, rather than hyphenating, was a testament to the strength of their union and shared artistic identity.

The Californian Impressionist: Style and Subject

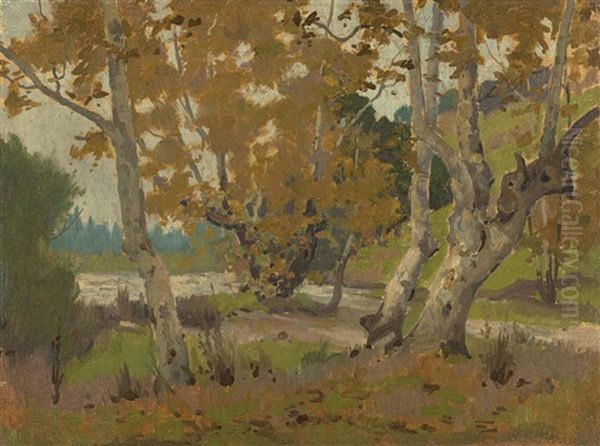

Elmer Wachtel is best categorized as a Californian Impressionist, though his style also bore traces of the earlier Barbizon School and Tonalism. His work, particularly in his mature period, is characterized by a keen observation of light and atmospheric effects, hallmarks of Impressionism. He was less concerned with the broken brushwork of French Impressionism and more focused on capturing the overall mood and the unique clarity of the California light.

His landscapes often feature a strong sense of composition, sometimes with a shadowed foreground leading the eye towards a sunlit middle ground and distant, hazy mountains – a technique reminiscent of Barbizon painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Wachtel had a particular fondness for the rolling hills, majestic oak trees, and sycamores of Southern California. The San Gabriel Mountains, the Sierra Madre range, and the coastal regions near Laguna Beach and Monterey frequently appeared in his work. He was adept at conveying the vastness and serenity of these landscapes, often imbuing them with a poetic, almost ethereal quality.

Unlike some of his contemporaries, such as William Wendt, whose landscapes often possess a rugged, almost monumental grandeur, Wachtel's paintings tend to be more lyrical and intimate, even when depicting expansive scenes. His palette, initially somewhat more subdued and tonal, brightened over time, reflecting the Impressionist concern with capturing the fleeting effects of light and color. He was particularly skilled at rendering the soft, diffused light of early morning or late afternoon, and the subtle gradations of color in the California sky.

The Arroyo Seco, near his Pasadena home, was a recurring subject. This area, with its winding stream, native trees, and dramatic canyon walls, provided endless inspiration for many artists of the period, including Hanson Puthuff, another prominent landscape painter known for his depictions of California's hills and deserts. Wachtel's interpretations of the Arroyo often highlight its tranquil beauty and the interplay of light filtering through the trees.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

While Elmer Wachtel was a prolific painter, a few works can be highlighted to illustrate his artistic concerns and stylistic evolution.

One of his well-regarded pieces is often titled along the lines of "California Landscape with Oaks" or similar descriptive titles focusing on the quintessential elements of the Southern California scenery he favored. These paintings typically showcase his mastery in depicting the gnarled forms of native oak trees, set against rolling golden hills under a luminous sky. The play of light on the foliage and the sense of deep, receding space are characteristic.

"Sunlight and Shadow" is a title that could apply to many of his works, as this dynamic interplay was central to his vision. In such pieces, he would skillfully contrast areas of bright illumination with cooler, shadowed passages, creating a sense of depth and vibrancy. His ability to capture the warmth of California sunshine without sacrificing tonal harmony was a key strength.

His depictions of the "Arroyo Seco" are particularly significant. These works often convey a sense of peaceful seclusion, with the gentle flow of the stream and the dappled light creating a serene atmosphere. The rich greens of the sycamores and willows, contrasted with the ochres and browns of the canyon slopes, demonstrate his sensitive color handling.

Works like "Moss Beach, Monterey, California" show his engagement with the coastal landscape. Here, the ruggedness of the coastline, the characteristic cypress trees, and the atmospheric effects of the Pacific Ocean would be rendered with his typical blend of realism and poetic sensibility. The light along the coast, often softer and more diffused than inland, offered different challenges and opportunities that Wachtel embraced.

An earlier piece, "Mission San Juan Capistrano at Sunset," likely a watercolor, points to his interest in California's historical landmarks and his versatility across mediums. The warm glow of sunset on the adobe walls of the mission would have allowed him to explore a rich, tonal palette, capturing a sense of history and romance.

Throughout his oeuvre, there is a consistent feeling of reverence for the natural world. His paintings are not merely topographical records; they are emotional responses to the beauty and spirit of the California landscape. This aligns him with other California Impressionists like Granville Redmond, known for his vibrant poppy fields and moonlit nocturnes, and Franz Bischoff, celebrated for his floral still lifes and later, his Impressionistic landscapes.

A Community of Artists: Contemporaries and Influences

Elmer Wachtel did not operate in an artistic vacuum. He was part of a thriving community of artists in Southern California who were collectively shaping a regional school of landscape painting. He was a member of the California Art Club, founded in 1909, which became a vital organization for exhibiting and promoting the work of local artists. Other prominent members included many of the names already mentioned, such as Guy Rose, William Wendt, Benjamin Brown, and Hanson Puthuff.

The influence of earlier California painters like Thomas Hill and Albert Bierstadt, known for their grand, panoramic views of Yosemite and the Sierras in the Hudson River School tradition, was still felt, but Wachtel and his contemporaries were forging a new path, one more aligned with Impressionist aesthetics. They were more interested in capturing the subjective experience of light and atmosphere than in detailed, almost photographic, representation.

The artistic environment also included figures like Edgar Payne, famous for his dramatic Sierra Nevada landscapes and depictions of fishing boats, and Alson Skinner Clark, who, like Guy Rose, had direct experience with French Impressionism. While each artist had a unique style, they shared a common goal: to interpret the distinctive character of the California landscape. The camaraderie and mutual influence within this group were significant factors in the development of California Impressionism. Even artists with slightly different stylistic leanings, such as Maurice Braun, known for his more mystical and spiritual interpretations of the landscape, were part of this broader artistic conversation.

The Wachtels, Elmer and Marion, were central figures in this community. Their Arroyo Seco home and studio became a gathering place for fellow artists and art lovers. They actively participated in exhibitions, both locally and nationally, helping to bring California art to a wider audience.

The Wachtel Studio and Artistic Practice

The Wachtel home and studio in the Arroyo Seco, designed by Elmer himself, was more than just a place to live and work; it was an embodiment of their artistic life. It included a dedicated exhibition space where they could display their own work and host showings for others. This integration of living, creating, and exhibiting was characteristic of the Arts and Crafts ethos prevalent at the time.

Their artistic practice often involved extensive travel. They explored the diverse terrains of California, from the deserts to the mountains to the coast. These sketching trips were essential for gathering material and inspiration. Elmer would typically make oil sketches on location (en plein air), capturing the immediate impressions of light and color. These sketches would then serve as a basis for larger, more finished studio paintings. Marion, often working in watercolor, could complete her works more readily on site.

Their shared passion for the landscape and their complementary artistic skills created a unique synergy. While they maintained their individual artistic identities, their work from this period often shares a similar sensibility, a testament to their close personal and professional bond. They were known for their dedication and prolific output, contributing significantly to the body of work that defines early California Impressionism.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Elmer Wachtel continued to paint actively throughout the 1910s and 1920s, his reputation as one of California's foremost landscape painters firmly established. His work was widely exhibited and collected, and he received numerous accolades. He and Marion also undertook painting expeditions further afield, including trips to the Grand Canyon and the deserts of Arizona and New Mexico, expanding their repertoire of Western landscapes.

Tragically, Elmer Wachtel's life was cut short. In the summer of 1929, while on a painting trip with Marion in Guadalajara, Mexico, he suddenly fell ill and passed away on August 31, at the age of 65. His death was a significant loss to the California art community. Marion Kavanagh Wachtel, deeply affected by his passing, largely ceased painting in oils, the medium most associated with her husband, and focused almost exclusively on watercolors for the remainder of her career, which extended until her own death in 1954.

Elmer Wachtel's legacy endures through his sensitive and evocative depictions of the California landscape. His paintings capture a specific era in the state's history, a time when its natural beauty was beginning to be widely recognized and celebrated through art. He was a key figure in the development of a distinct regional style of Impressionism, one that responded to the unique light and topography of the American West.

His works are held in numerous private and public collections, including the Irvine Museum, which specializes in California Impressionism, the Laguna Art Museum, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Along with contemporaries like Jack Wilkinson Smith, known for his coastal scenes and Sierra views, and Colin Campbell Cooper, who painted cityscapes as well as landscapes, Wachtel helped to define an artistic movement that continues to be appreciated for its beauty and historical significance.

Conclusion: A Lasting Impression

Elmer Wachtel's journey from musician to painter, from the East Coast to the sun-drenched landscapes of California, is a compelling story of artistic evolution and dedication. His ability to translate the visual poetry of the California scene onto canvas, with its nuanced light, subtle color harmonies, and serene atmosphere, marks him as a distinguished practitioner of American Impressionism. His partnership with Marion Kavanagh Wachtel further enriches his story, highlighting a unique collaboration that contributed significantly to the cultural heritage of California.

Today, as we look back at the early 20th century, Elmer Wachtel's paintings serve as more than just beautiful objects; they are historical documents, capturing the essence of a California that, while changed, still resonates with the spirit he so masterfully conveyed. His art invites us to pause and appreciate the enduring beauty of the natural world, seen through the eyes of an artist who found his true voice in the landscapes of the Golden State. His contribution, alongside his gifted wife and their talented contemporaries, ensures that the light of early California Impressionism continues to shine brightly.