Benno Raffael Adam (1812-1892) stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century German art. Born into an esteemed artistic dynasty in Munich, the vibrant capital of Bavaria, Adam carved a distinct niche for himself as a preeminent painter of animals. His life spanned a period of immense artistic change, yet he remained steadfastly dedicated to the detailed and empathetic portrayal of the animal kingdom, particularly within the contexts of the hunt, pastoral life, and domestic settings. His work, deeply rooted in the traditions of the Munich School, offers a fascinating window into the cultural preoccupations and artistic sensibilities of his time.

An Artistic Heritage: The Adam Family of Painters

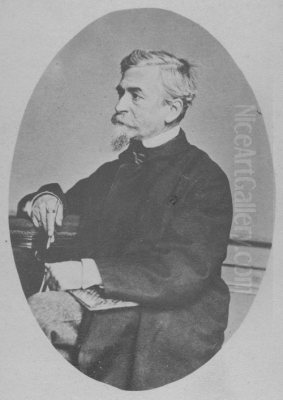

Benno Adam's artistic journey began under the most auspicious circumstances. He was born in Munich on July 15, 1812, the eldest son of the highly respected painter Albert Adam (1786-1862). Albert was himself a renowned artist, celebrated for his depictions of battles, horses, and military life, having famously documented Napoleon's Russian campaign. Growing up in such an environment meant that Benno was immersed in art from his earliest years. The studio was his playground, and the principles of drawing, composition, and observation were absorbed almost by osmosis.

The Adam family name became synonymous with art in Munich. Benno's younger brothers, Eugen Adam (1817-1880) and Franz Adam (1815-1886), also became successful painters, specializing in genre scenes, military subjects, and equestrian portraits, respectively. Another relative, Emil Adam (1843-1924), continued the tradition into the next generation, focusing primarily on horses and portraits. This familial concentration of artistic talent created a supportive yet potentially competitive environment, likely spurring Benno to define his own specific area of expertise within the broader field favoured by his family. His father, Albert, was undoubtedly his first and most influential teacher, grounding him in the fundamentals of academic drawing and painting.

The Munich School and the Rise of Animal Painting

Munich in the 19th century was a major European art center, rivaling Paris and Vienna. Under the patronage of the Bavarian monarchy, particularly King Ludwig I, the city fostered a thriving artistic community and established prestigious institutions like the Academy of Fine Arts. The dominant artistic trend that emerged became known as the Munich School, characterized by its emphasis on realism, masterful technique, often dark tonal palettes influenced by Dutch Old Masters, and a focus on genre scenes, historical subjects, portraiture, and landscape.

Within this environment, Tiermalerei, or animal painting, flourished. This was partly driven by the cultural importance of hunting among the aristocracy and the growing middle class, creating a demand for scenes depicting the chase and its quarry. Furthermore, the Biedermeier period's appreciation for nature and domestic life extended to the affectionate portrayal of farm animals and pets. Benno Adam emerged as one of the leading exponents of this genre, alongside contemporaries who also specialized in or frequently depicted animals.

Specialization: The World of Animals

While his father Albert was famed for horses in military contexts, Benno Raffael Adam broadened his scope to encompass a wider array of animals, though dogs and game animals remained central to his oeuvre. He developed an exceptional ability to capture not just the physical likeness of his subjects but also their characteristic movements, postures, and even perceived temperaments. His paintings often feature hunting dogs – pointers, setters, hounds – depicted with an understanding born of close observation, showcasing their alertness, loyalty, and energy.

His hunting scenes are particularly noteworthy. Works like Hirschjagd (Deer Hunt), painted around 1860, exemplify his skill in composing dynamic narratives. These paintings often depict the climax of the hunt, the interaction between eager dogs and cornered game, set against meticulously rendered forest or mountain backdrops. He captured the tension and drama of the moment, appealing directly to patrons who were often avid hunters themselves. His depictions of deer, foxes, and other game animals were anatomically precise, showing a keen understanding of wildlife.

Beyond the thrill of the hunt, Adam also excelled in portraying domestic animals and pastoral scenes. His painting Rinder in Gebirgslandschaft (Cattle in a Mountain Landscape) from 1849 showcases his ability to place animals convincingly within their natural environment. He painted cattle, sheep, goats, and horses with the same attention to detail and sympathetic eye. Works like Eselslute mit Fohlen (Donkey with Foal), which appeared at auction, highlight his interest in the quieter moments of animal life, capturing maternal bonds or the simple presence of animals in the landscape.

Artistic Style and Technique

Benno Adam's style is firmly rooted in the Realism characteristic of the Munich School. He prioritized accurate observation and detailed rendering. His brushwork is generally fine and controlled, allowing him to meticulously depict the texture of fur, the musculature of animals, and the specifics of landscape elements. He possessed a strong understanding of animal anatomy, which lent authenticity to his portrayals, whether the animals were in motion or at rest.

His compositions are typically well-balanced, focusing attention clearly on the animal subjects. In hunting scenes, he employed dynamic arrangements to convey action and excitement. In pastoral or domestic scenes, the compositions are often calmer, emphasizing the peaceful integration of animals into their surroundings. His use of light is naturalistic, effectively modeling forms and creating atmosphere, whether it be the dappled sunlight of a forest clearing or the softer light of a stable interior. While predominantly realistic, some of his works, particularly those featuring dramatic landscapes or the intensity of the hunt, can possess undertones of the Romantic sensibility that lingered in German art.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Benno Adam worked during a vibrant period for German art, particularly in Munich. He was a contemporary of numerous talented artists, some of whom shared his interest in animal painting or related genres. His father, Albert Adam, remained a significant figure throughout Benno's early career. His brothers, Eugen and Franz Adam, were also active participants in the Munich art scene.

Within the specific field of animal painting in Munich, artists like Anton Braith (1836-1905) and Christian Mali (1832-1906) became prominent, particularly known for their depictions of sheep and cattle, often in Alpine settings. While their focus differed slightly from Adam's emphasis on hunting dogs and game, they shared a commitment to realistic portrayal. Heinrich von Zügel (1850-1941), though slightly younger, became a leading figure in animal painting towards the end of Adam's life, known for his more impressionistic handling. Friedrich Voltz (1817-1886) was another Munich contemporary noted for his landscapes often populated with cattle.

Looking at broader Munich School figures, Adam's work can be seen alongside the detailed genre scenes of Carl Spitzweg (1808-1885), who captured the Biedermeier spirit, or the historical and battle paintings influenced by Wilhelm von Kobell (1766-1853), whose precision in depicting horses might have been an early influence passed down through Albert Adam. While stylistically different, the realism promoted by artists like Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900) later in the century underscores the ongoing importance of observational accuracy in Munich. Internationally, Adam's dedication to animal subjects finds parallels in the work of Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) in Britain, famous for his dramatic stag paintings and sentimental dog portraits, and Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) in France, renowned for her powerful depictions of horses and farm animals. Mentioning Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), a key German Romantic landscape painter, helps contextualize the earlier artistic climate from which Munich Realism partly evolved. Adolph Menzel (1815-1905) in Berlin represents another major figure in German Realism, though with a different focus.

While the provided snippets mentioned a connection to the Chiemsee school, this artists' colony primarily flourished later in the 19th century and was more focused on plein-air landscape painting. While Adam undoubtedly depicted Bavarian landscapes, including areas potentially near Lake Chiemsee, and may have known artists associated with the colony, classifying him as a member of the Chiemsee school itself requires more specific evidence. His primary affiliation remains with the mainstream Munich School and its tradition of studio-based realism. Information regarding specific collaborations or documented rivalries with these contemporaries is scarce, but they certainly formed the competitive and collegial backdrop against which he worked.

Later Life, Legacy, and Collections

Benno Raffael Adam continued to paint throughout his long life. He remained based primarily in Munich, the center of his professional world. He passed away in Kelheim, a town on the Danube in Bavaria, on March 8, 1892, at the age of 79. He left behind a substantial body of work that solidified his reputation as one of Germany's foremost animal painters of the 19th century.

His legacy lies in his mastery of the Tiermalerei genre. He elevated the depiction of animals, particularly hunting dogs and game, through his technical skill and empathetic observation. His works were popular during his lifetime, sought after by patrons who admired both their artistic merit and their subject matter, which resonated with aristocratic and bourgeois interests in hunting and the countryside. He successfully carried forward the artistic tradition established by his father, contributing significantly to the reputation of the Adam family as a dynasty of painters.

Today, Benno Raffael Adam's paintings are appreciated for their historical value, offering insights into 19th-century German culture, particularly the significance of hunting and the relationship between humans and animals. They are also valued for their intrinsic artistic quality – the detailed realism, the skillful compositions, and the ability to capture the vitality of his subjects.

His works regularly appear on the art market and achieve respectable prices at auction, particularly those featuring his most characteristic subjects like deer hunts or detailed studies of dogs. While the initial prompt noted uncertainty about museum collections, works by prominent Munich School artists like Benno Adam are typically represented in major German and Austrian museums, especially those with significant 19th-century holdings. Collections such as the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, the Lenbachhaus, or other regional Bavarian museums would be logical repositories for his paintings, although specific inventories require detailed checks of museum databases. His art continues to appeal to collectors of sporting art, historical German painting, and animal portraiture.

Conclusion

Benno Raffael Adam was more than just a painter of animals; he was a chronicler of a specific aspect of 19th-century Bavarian life and a master craftsman within the esteemed Munich School tradition. Born into art, he honed his skills under the guidance of his famous father, Albert Adam, and alongside his talented brothers, Eugen and Franz. He specialized in a genre that perfectly suited his talents for detailed observation and anatomical accuracy, bringing hunting scenes, pastoral landscapes, and animal portraits to life with remarkable skill and sensitivity. His paintings of loyal hunting dogs, majestic stags, and tranquil cattle remain compelling examples of Tiermalerei at its finest. As a key member of the Adam artistic dynasty and a significant contributor to the Munich School, Benno Raffael Adam secured his place in the annals of German art history, leaving behind a legacy of works that continue to engage viewers with their realism, vitality, and connection to the natural world.