Berthe Morisot stands as one of the most significant figures of the Impressionist movement, a pioneering French painter whose work captured the nuances of modern life with a distinct sensitivity and grace. Born on January 14, 1841, and passing away on March 2, 1895, Morisot was not only a central member of the Impressionist circle but also a trailblazer for women in the arts. Her unique perspective, often focusing on the intimate world of women and family, combined with her innovative technique, secured her an indelible place in art history alongside contemporaries like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Berthe Morisot was born in Bourges, France, into an affluent and cultured bourgeois family. Her father, Edmé Tiburce Morisot, held a prominent position as a senior government official, eventually serving as a prefect. Her mother, Marie-Joséphine-Cornélie Thomas, possessed an artistic lineage herself, being the great-niece of the celebrated Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard. This connection to the arts likely fostered an environment where creative pursuits were encouraged, even for daughters in the conservative 19th century.

Berthe and her older sisters, Yves and Edma, received the private art education typical for young women of their social class. Initially, their parents envisioned it as a genteel accomplishment. However, Berthe and Edma demonstrated exceptional talent and dedication that surpassed mere hobbyism. Their first tutor was Geoffrey-Alphonse Chocarne, followed by Joseph Guichard, a former student of the Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres but also influenced by Eugène Delacroix. Guichard recognized their serious potential and reportedly warned their mother that their talent could lead them to become professional painters, a challenging path for women at the time.

A pivotal moment in Morisot's artistic development came when she and Edma began studying under the influential landscape painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot in the early 1860s. Corot, a key figure in the Barbizon School, encouraged outdoor (plein air) painting, a practice that profoundly shaped Morisot's approach to light and landscape. Under his guidance, she honed her observational skills and developed a lighter touch. Both Berthe and Edma achieved early recognition by having their works accepted into the prestigious, state-sponsored Paris Salon, starting in 1864. This marked their entry into the official art world, though Berthe would soon gravitate towards the more radical avant-garde.

Embracing Impressionism

The late 1860s marked a turning point for Morisot. While copying masterpieces in the Louvre, a common practice for art students, she likely met the painter Henri Fantin-Latour, who in turn introduced her to Édouard Manet in 1868. Manet, though never officially exhibiting with the Impressionists, was a central figure in the Parisian avant-garde, challenging academic conventions with his modern subjects and bold style. Morisot and Manet developed a close and complex relationship, marked by mutual admiration, artistic dialogue, and deep friendship.

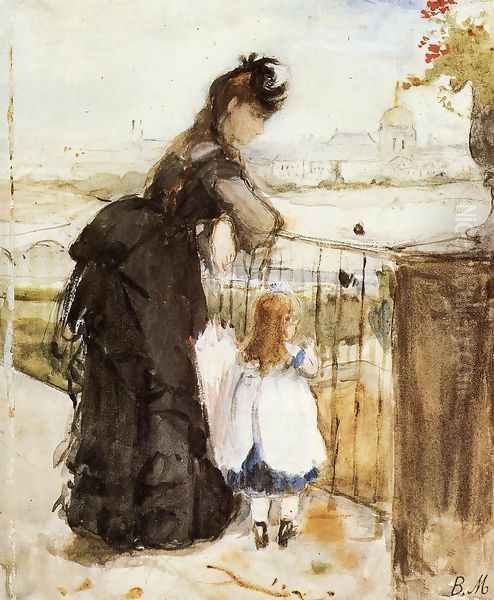

Morisot frequently posed for Manet, appearing in several of his important works, including The Balcony (1868-69), Repose (c. 1870), and numerous portraits like Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets (1872). This collaboration exposed her further to modernist ideas. Manet's influence is visible in her work from this period, particularly in figure painting, but Morisot maintained her distinct artistic personality, characterized by a lighter palette and more delicate brushwork.

Around the same time, Morisot formed a lasting friendship with Edgar Degas. Degas, known for his sharp observation and innovative compositions, also encouraged her artistic endeavors. Through these connections, Morisot became deeply integrated into the circle of artists who were dissatisfied with the constraints of the official Salon system and sought new ways to depict contemporary life. This group included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and Paul Cézanne.

Morisot fully committed to the burgeoning Impressionist movement and became one of its founding members. She was instrumental in organizing the first independent Impressionist exhibition, held in April 1874 in the former studio of the photographer Nadar. This exhibition, a defiant alternative to the official Salon, marked the public debut of Impressionism as a cohesive movement. Morisot exhibited several works, including her seminal painting The Cradle. Her participation underscored her dedication to the group's ideals of artistic independence and modern expression.

Artistic Style and Signature Themes

Berthe Morisot's art is quintessentially Impressionist, yet it possesses a unique voice and distinct characteristics. Her style evolved throughout her career but consistently emphasized the capture of fleeting moments, the effects of light, and a sense of immediacy. She employed rapid, feathery brushstrokes that created texture and vibrancy, often leaving areas of the canvas visible, contributing to the feeling of spontaneity.

Her palette was generally high-keyed and luminous, favoring whites, pale blues, greens, pinks, and yellows. She masterfully used color to convey light and atmosphere, whether depicting sun-dappled gardens, airy interiors, or the subtle play of light on fabric and skin. Unlike the sometimes more robust application of paint seen in Monet or Renoir, Morisot's touch often had a delicate, almost ethereal quality, particularly in her watercolors and pastels, mediums she handled with exceptional skill.

Morisot's subject matter largely centered on the world she knew best: the domestic lives of bourgeois women and children. Restricted by social conventions from accessing the same range of public subjects available to her male colleagues (like cafés, bars, or backstage scenes favored by Degas or Manet), she turned her gaze inward and onto her immediate surroundings. Her paintings frequently depict women reading, sewing, playing musical instruments, tending to children, or engaged in personal grooming within intimate interior settings.

This focus resulted in works of profound psychological insight and sensitivity. She portrayed her subjects – often family members, including her sister Edma and later her daughter Julie – with empathy and nuance, capturing quiet moments of reflection, tenderness, or even subtle melancholy. Her depictions of motherhood, such as The Cradle, are particularly renowned for their intimacy and lack of sentimentality. She also painted landscapes, seascapes, and garden scenes, often populated by elegantly dressed figures enjoying leisure activities, always rendered with her characteristic attention to light and atmosphere. Her practice of painting outdoors, learned from Corot, remained crucial throughout her career.

Crucially, Morisot's work offers a distinct "female gaze," presenting the lives and experiences of women from an insider's perspective. This contrasts with the often objectified or romanticized portrayals common in the work of some male artists of the era. Her art provides a valuable visual record of female bourgeois life in the late 19th century, rendered with both artistic brilliance and personal authenticity.

Marriage, Family, and Later Career

In 1874, the same year as the first Impressionist exhibition, Berthe Morisot married Eugène Manet, the younger brother of Édouard Manet. Eugène, himself an amateur painter and writer, was deeply supportive of his wife's career. Their marriage provided Morisot with financial stability and social respectability, allowing her to continue pursuing her demanding profession without the economic pressures faced by some artists. While she sometimes used "Madame Eugène Manet" socially, she continued to exhibit under her maiden name, Berthe Morisot, asserting her professional identity.

In 1878, their only child, Julie Manet, was born. Julie became a frequent and beloved subject in Morisot's paintings, appearing in numerous works that chronicle her growth from infancy through adolescence. Paintings like Eugène Manet and His Daughter at Bougival (1881) and The Dining Room (1886) showcase the intimate family life that Morisot skillfully balanced with her artistic production. Motherhood undoubtedly impacted her work, perhaps deepening her focus on domestic themes, but it did not halt her career.

Morisot remained a steadfast participant in the Impressionist exhibitions, contributing works to all but one (the fourth show in 1879, likely due to Julie's recent birth). She hosted gatherings for her fellow artists and writers at her home, fostering the intellectual and social life of the Impressionist circle. Her salon became a meeting place for figures like Degas, Renoir, Monet, and the Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé, who became a close family friend and later Julie's guardian.

Her artistic style continued to evolve in her later years. Her brushwork became even looser and more dynamic, sometimes approaching abstraction. She experimented with different techniques and compositions, always seeking to capture the essence of her subject with freshness and vitality. Despite the eventual dissolution of the Impressionist group exhibitions in 1886, Morisot continued to paint prolifically and exhibit her work, including a successful solo show in 1892.

Key Relationships and Influence

Berthe Morisot's position within the Impressionist movement was solidified not only by her art but also by her strong relationships with its key members. Her bond with Édouard Manet was particularly significant in her early career, providing mentorship and encouragement, though she quickly developed her own independent path. Manet clearly respected her talent, incorporating her suggestions into his own work at times.

Her friendship with Edgar Degas was one of mutual respect and artistic exchange. They shared an interest in capturing modern life and experimenting with composition. Degas admired her work greatly, acquiring some of her paintings for his personal collection. She also maintained warm friendships with Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, sharing exhibition spaces and artistic ideals with them for years. Renoir, in particular, shared her interest in depicting figures and scenes of bourgeois life, though with a different stylistic approach.

Morisot's connection with Mary Cassatt, the American expatriate painter who also joined the Impressionist circle, is noteworthy. As the two most prominent women within the group, they shared similar challenges navigating the male-dominated art world and often focused on themes of women and children. While they were friends and respected each other's work, their artistic styles remained distinct, with Cassatt often employing firmer lines and more structured compositions influenced by Degas and Japanese prints.

Morisot's influence extended beyond her immediate circle. Her commitment to her profession and the quality of her work served as an inspiration for subsequent generations of female artists seeking to pursue careers in the arts. Although perhaps less overtly radical than some of her male counterparts in terms of subject matter, her technical innovation and unique perspective contributed significantly to the overall richness and diversity of the Impressionist movement. Figures like Gustave Caillebotte, another Impressionist known for depicting modern Parisian life, were part of her social and artistic milieu. Her focus on intimate domestic scenes also resonates with the later work of Post-Impressionist painters like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who explored similar themes within the Nabis group.

Notable Works

Berthe Morisot produced a rich body of work throughout her career. Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of her style and thematic concerns:

The Cradle (Le Berceau, 1872): Perhaps her most famous work, it depicts her sister Edma Pontillon gazing tenderly at her sleeping daughter, Blanche. Exhibited at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, it exemplifies Morisot's intimate portrayal of motherhood and domestic life, rendered with delicate brushwork and subtle lighting.

Summer's Day (Jour d'été, c. 1879): This vibrant painting shows two elegantly dressed women in a boat on the Bois de Boulogne lake. It captures the fleeting effects of sunlight on water and figures with energetic, broken brushstrokes typical of high Impressionism. The work radiates light and leisure, showcasing Morisot's skill in plein air painting.

Woman at Her Toilette (Femme à sa toilette, c. 1875/80): This intimate scene depicts a woman before her dressing table, a common theme for Impressionists like Degas. Morisot's version is characterized by its soft light, silvery tones, and loose, almost dissolving brushwork, creating an atmosphere of private contemplation.

Reading (La Lecture, 1873): Featuring her sister Edma reading on a sofa, this painting highlights Morisot's ability to capture quiet, everyday moments with psychological depth. The composition and handling of light create a serene yet engaging scene.

Eugène Manet and His Daughter at Bougival (Eugène Manet et sa fille à Bougival, 1881): A charming depiction of her husband and young daughter Julie in a garden setting. The work showcases her looser, more fluid style of the 1880s and her continued focus on family life.

The Dining Room (Dans la salle à manger, 1886): This later work portrays Julie Manet and a maid in the family dining room. The brushwork is exceptionally free and dynamic, demonstrating Morisot's ongoing experimentation and mastery of capturing light and movement within an interior space.

These works, among many others, illustrate Morisot's consistent themes, her evolving style, and her significant contribution to the Impressionist aesthetic.

Legacy and Recognition

Berthe Morisot died tragically young on March 2, 1895, from pneumonia contracted while nursing her daughter Julie through the same illness. She was only 54 years old. At the time of her death, her work was respected within avant-garde circles but had not achieved the widespread fame or financial success of some of her male colleagues like Monet or Renoir. Her death certificate famously listed her as having "no profession," a stark reflection of the societal disregard for women's professional identities, even for an artist of her stature.

Following her death, her friends and fellow artists, including Degas, Renoir, Monet, and Mallarmé, organized a major retrospective exhibition of her work in 1896 to honor her memory and secure her artistic legacy. While appreciated by connoisseurs, her reputation languished somewhat during the early 20th century, overshadowed by the narratives centered on male Impressionists. Gender bias and the critical tendency to categorize her work as merely "feminine" or "charming" often obscured the true extent of her innovation and artistic power.

However, the later 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a significant reassessment of Berthe Morisot's contribution to art history. Feminist art historians played a crucial role in highlighting her achievements and challenging the male-centric view of Impressionism. Today, she is widely recognized as one of the central figures of the movement, admired for her technical mastery, her unique perspective, her bold experimentation with form and color, and her sensitive portrayal of modern life.

Her work is celebrated in major museums worldwide, and she is acknowledged not only as a great Impressionist painter but also as a crucial figure in the history of women artists. She successfully navigated the significant social and professional obstacles faced by women in her time to create a body of work that remains fresh, engaging, and profoundly beautiful. The diary kept by her daughter, Julie Manet, provides invaluable insights into Morisot's life, her art, and the vibrant world of the Impressionists she inhabited.

Conclusion

Berthe Morisot was more than just a member of the Impressionist group; she was one of its most consistent and innovative practitioners. From her early studies with Corot to her central role in the Impressionist exhibitions and her later stylistic evolution, she forged a unique artistic path. Her focus on the intimate lives of women and children, rendered with luminous color and dynamic brushwork, offered a vital perspective within the broader movement. As a pioneering professional female artist, she challenged conventions and created a legacy that continues to inspire. Berthe Morisot's vision, sensitivity, and unwavering dedication to her art secure her place as a true visionary of Impressionism and a major figure in the history of modern painting.