Jacqueline Marval, born Marie-Joséphine Vallet (1866-1932), stands as a significant yet often overlooked figure in the vibrant landscape of French modern art. Active during a period of radical artistic transformation in Paris, Marval was a key participant in the Fauvist movement, known for her bold use of color, expressive brushwork, and a distinct focus on the female form and experience. Though recognized by prominent peers and critics during her lifetime, her contributions were subsequently overshadowed, only to be rediscovered and re-evaluated in recent decades. Her journey from provincial France to the heart of the Parisian avant-garde is a testament to her resilience and artistic vision.

Early Life and Unconventional Path to Art

Born in Quaix-en-Chartreuse, near Grenoble in southeastern France, Marie-Joséphine Vallet's early life did not obviously point towards a career in the avant-garde art world. Following societal expectations, she initially pursued a more conventional path, obtaining her teaching qualification in 1884. However, the classroom was not her destiny. Personal circumstances, including a marriage in 1886 to a traveling salesman named Albertin Valentin, followed by a divorce in 1891 and the tragic loss of her infant son that same year, profoundly altered her life's trajectory.

Seeking a new beginning and needing to support herself, Vallet moved to Paris. Initially, she relied on her skills as a seamstress and embroiderer, trades that perhaps subtly honed her sense of color and composition. It wasn't until her late twenties or early thirties, around 1895, that she fully committed to becoming a painter. Largely self-taught, she began her artistic journey, initially exhibiting under the pseudonym "Marie Jacques" before adopting the name Jacqueline Marval, under which she would gain recognition.

Arrival in Paris and Artistic Debut

Paris at the turn of the 20th century was a crucible of artistic innovation. Marval quickly immersed herself in this stimulating environment. She formed crucial relationships with fellow artists who would become lifelong friends and colleagues. Among the most significant was her encounter with the painter Jules Flandrin, also from the Grenoble region, with whom she developed a close personal and professional relationship. Through Flandrin and her own burgeoning presence, she connected with key figures associated with Gustave Moreau's studio and the nascent Fauvist movement, including Henri Matisse and Albert Marquet.

Marval's official entry into the Parisian art scene occurred at the Salon des Indépendants. Although her initial submissions in 1900 were reportedly rejected, she persevered. In 1901, her work was accepted and exhibited at the Salon, marking a significant milestone. This exhibition placed her alongside contemporaries like Matisse and Marquet, signaling her arrival within the avant-garde circles. Her talent soon caught the eye of the pioneering gallerist Berthe Weill, who played a crucial role in promoting modern artists, including Pablo Picasso and Matisse. Weill began exhibiting Marval's work in her gallery as early as 1902, providing vital support and visibility.

Embracing Fauvism

The early years of the 20th century witnessed the explosive arrival of Fauvism, a movement characterized by its revolutionary use of intense, non-naturalistic color and bold, often spontaneous brushwork. The name "Fauves" (wild beasts) was famously coined by critic Louis Vauxcelles at the 1905 Salon d'Automne in response to the startling vibrancy of works by Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and others. Fauvism prioritized emotional expression and decorative effect over realistic representation, drawing inspiration from Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh and Gauguin, as well as non-Western art forms.

Jacqueline Marval was an integral part of this movement. Her paintings from this period fully embraced the Fauvist ethos. She employed strident colors, applied with a freedom and energy that conveyed powerful emotion and visual excitement. Her association with core Fauves was close; she exhibited alongside Matisse, Marquet, Derain, and Kees van Dongen, and engaged in the ongoing dialogue about the new possibilities of painting. Her work contributed to the Fauvist exploration of color's autonomous power and the simplification of form for expressive impact.

Signature Style and Thematic Concerns

While clearly aligned with Fauvism, Marval developed a distinct artistic voice. Her style is characterized by several key elements. Color remained paramount throughout her career – often vibrant, applied in bold patches, yet capable of surprising subtlety and harmony. She masterfully used color not just for description but to build form, create mood, and evoke sensory experience. Her brushwork was equally distinctive: energetic, free, yet controlled, defining forms with confidence and adding texture and dynamism to the canvas.

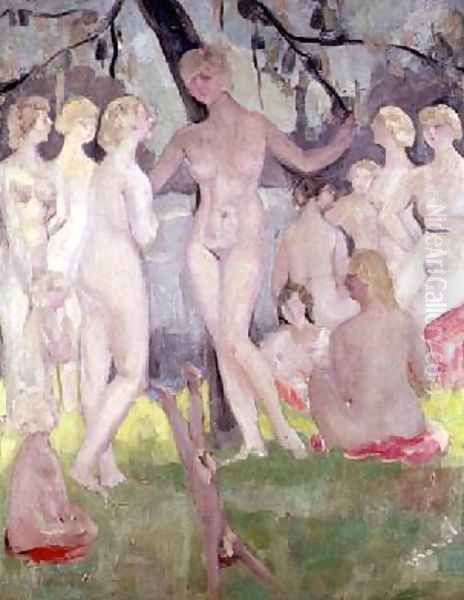

Marval's subject matter was diverse, encompassing still lifes (particularly flowers), landscapes, scenes of modern leisure (like circuses and beaches), and portraits. However, she is perhaps best known for her depictions of women. Unlike many male contemporaries whose female subjects often fit traditional archetypes, Marval portrayed women with a sense of agency, self-possession, and complex interiority. Her nudes are sensual yet often imbued with a dreamlike or poetic quality, suggesting psychological depth rather than mere objectification.

This focus on the female experience from a woman's perspective was groundbreaking for its time. Marval explored various facets of femininity, from domesticity to sensuality, independence, and camaraderie between women. She notably refused to be pigeonholed or segregated in exhibitions purely for female artists, choosing instead to exhibit alongside her male peers like Matisse and Marquet, asserting her place in the broader art world based on merit, not gender. This stance reflected a quiet but firm feminist consciousness.

Key Works

Several paintings stand out as representative of Marval's oeuvre and her contribution to modern art. Les Odalisques (The Odalisques), painted around 1902-1903, is arguably her most famous early work. Depicting a group of reclining female nudes in an exoticized setting, it exemplifies her Fauvist use of bold color and simplified forms. The work predates Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) and has often been compared to Matisse's explorations of similar themes, such as his Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) (1907). Some accounts note Matisse's surprise upon seeing Marval's Odalisques, suggesting its early impact. The painting showcases her ability to blend decorative patterns with sensuous figuration.

The Beach (La Plage), dated 1923, represents her later style. It captures the light, movement, and atmosphere of a seaside scene with vibrant colors and dynamic composition. The work reflects her enduring interest in capturing modern life and her skill in rendering the effects of light and shadow in an expressive, non-naturalistic manner. It speaks to her love of nature and her ability to convey vitality and joy through paint.

Other notable works include Danseuse de café (Café Dancer, 1904), which captures the ambiance of Parisian nightlife, and Les Cigales (The Cicadas, 1906), an oil painting praised for its delicate handling of color and light, demonstrating her keen observation of the natural world. Beyond oil painting, Marval was proficient in various media, including lithography, watercolor, pastels, and even sculpture, showcasing her versatility and continuous exploration of artistic forms.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Marval's career unfolded within a rich network of artistic friendships and collaborations. Her relationship with Jules Flandrin was particularly significant, both personally and professionally; they shared studios at times and even collaborated on works, such as The Melon (1925). Her connection to the core Fauvist group was strong. She maintained a long friendship and mutual respect with Henri Matisse, exhibiting alongside him frequently from their early days at the Salon des Indépendants and Berthe Weill's gallery.

She also shared a close artistic dialogue with Albert Marquet, another key Fauve known for his subtle color harmonies and depictions of Paris. Their correspondence and shared exhibition history between 1901 and 1905 attest to their mutual influence. Georges Rouault, known for his powerful, stained-glass-like paintings, was another friend with whom Marval reportedly shared living and working spaces at times.

Her circle extended to include other prominent figures of the era. She was acquainted with André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, central figures of Fauvism. She knew Pierre Bonnard, a leading member of the Nabis group, and was connected within the broader Parisian art world that included Pablo Picasso. She also interacted with fellow female artists like Marie Laurencin. Gallerist Berthe Weill remained a crucial supporter. This web of relationships underscores Marval's active participation in the artistic life of her time, engaging with diverse talents such as Kees van Dongen, Raoul Dufy, Othon Friesz, and potentially early Georges Braque through Fauvist circles.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Throughout her career, Marval exhibited her work regularly and gained considerable recognition within the art world, even if she didn't achieve the widespread fame of some male counterparts. Her debut at the Salon des Indépendants in 1901 was followed by consistent participation in major Parisian Salons, including the Salon d'Automne, where Fauvism famously erupted. She frequently showed work at Berthe Weill's gallery, a hub for the avant-garde.

Her reputation extended beyond France. Significantly, her work was included in the landmark Armory Show of 1913, which introduced European modern art to American audiences on a large scale. This inclusion placed her alongside the leading modernists of the day. Later in her career, she continued to exhibit, with shows in France and even as far as Japan in 1926. She was also involved in initiatives supporting modern art, including plans for the creation of modern art museums in Paris and her native Grenoble in the 1920s.

Critical reception during her lifetime acknowledged her talent. Fellow artists like Matisse and Marquet expressed admiration for her work in their correspondence. Critics noted the strength and originality of her painting. However, like many women artists of her generation, securing lasting institutional recognition and market success comparable to leading male artists proved challenging.

Later Life and Posthumous Rediscovery

Jacqueline Marval continued to paint and exhibit into the later years of her life, adapting her style while retaining her characteristic vibrancy. She passed away in Paris in 1932 at the age of 66. Following her death, her work gradually faded from mainstream art historical narratives, a fate shared by numerous talented women artists overshadowed by their male contemporaries in the mid-20th century canon.

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a resurgence of interest in Marval's art. Driven by a broader reassessment of art history to include marginalized voices, particularly women artists, scholars and curators began to rediscover her contributions. Her bold Fauvist works, her sensitive and modern depictions of women, and her unique position within the Parisian avant-garde started receiving fresh attention.

This renewed interest has been formalized by the establishment of the Comité Jacqueline Marval in 2020 by the artist's family. This committee is dedicated to promoting her work, authenticating pieces, and restoring her rightful place in the history of modern art through research, publications, and supporting exhibitions. Her paintings are now found in the collections of several important French museums, including the Musée de Grenoble, the Musée d'Arts de Nantes, and potentially the Petit Palais (Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris) and the Musée de la Vie Romantique. Her works also appear at auction, indicating a growing market appreciation.

Legacy and Conclusion

Jacqueline Marval was more than just a participant in Fauvism; she was an innovator who brought a unique sensibility to the movement and to modern painting in general. Her fearless use of color, dynamic compositions, and particularly her insightful and empathetic depictions of women distinguish her work. She navigated the male-dominated art world of early 20th-century Paris with determination, creating a body of work that is both historically significant and visually compelling.

Her legacy lies in her contribution to the Fauvist revolution of color and form, her pioneering exploration of female identity and experience from an authentic female viewpoint, and her creation of vibrant images that capture the spirit of modernity. While overshadowed for a period, Jacqueline Marval's rediscovery enriches our understanding of French modernism, highlighting the diverse talents that shaped this pivotal era. Her art continues to resonate today, celebrated for its boldness, its beauty, and its enduring relevance.