Introduction: A Life Intertwined with Impressionism

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet stands as a fascinating, though often overlooked, figure within the vibrant tapestry of French Impressionism. Born in Paris on November 10, 1865, and passing away on December 8, 1947, her life was inextricably linked with the movement's central figure, Claude Monet. She was not only his stepdaughter but also became his daughter-in-law, and crucially, she was a talented painter herself, developing her own distinct Impressionist voice while working in the shadow of her famous stepfather. Her journey offers a unique perspective on the Impressionist circle, the challenges faced by female artists of the era, and the intimate daily life within Monet's Giverny sanctuary.

Her parentage placed her at the heart of the art world from a young age. She was the second daughter of Ernest Hoschedé, a wealthy department store magnate and an early, crucial patron of Impressionist artists, including Monet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley. Her mother, Alice Raingo, later became Monet's second wife. This complex familial situation meant Blanche grew up surrounded by art, artists, and the revolutionary ideas that were reshaping the European visual landscape.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Monet's Orbit

Blanche's childhood was marked by the fluctuating fortunes of her father, Ernest Hoschedé. Initially enjoying a life of luxury, the family resided in Paris and later at the lavish Château de Rottembourg, southeast of the city. Ernest's enthusiastic collecting and patronage, however, contributed to his financial ruin. By 1877, he was bankrupt, forcing the sale of his impressive art collection. This downturn led to a pivotal moment in Blanche's life and the history of Impressionism.

In 1878, seeking refuge and support, the Hoschedé family – Alice and her six children – moved in with Claude Monet and his ailing wife, Camille, along with their two sons, Jean and Michel, in the town of Vétheuil along the Seine. This unusual merged household, born of financial necessity and shared artistic sympathies, created a unique environment. Blanche, then a young teenager, was immersed daily in Monet's world, observing his relentless dedication to capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere.

Even before this move, Blanche had shown an early interest in art. Sources suggest she began exploring painting around the age of eleven. Living in close proximity to Monet undoubtedly fanned this flame. She spent countless hours watching him work, absorbing his techniques and his philosophy of painting directly from nature (en plein air). While Monet was famously reluctant to take on formal pupils, Blanche's position within the household granted her unparalleled access and informal guidance.

The family's subsequent moves, first to Poissy and then, crucially, to Giverny in 1883, further cemented Blanche's connection to Monet's artistic practice. Giverny, with its house, gardens, and surrounding Normandy landscapes, would become the central stage for both Monet's later masterpieces and Blanche's own artistic development. It was here that her informal apprenticeship truly blossomed.

The Sole Protégée: Assistant and Student to Monet

By the time she was seventeen, around the period the combined families settled in Giverny, Blanche Hoschedé had become more than just an observer; she was actively involved in Monet's artistic life. She is often described as his only true student and assistant. This role was multifaceted. She prepared his canvases, organized his palettes, and, most importantly, accompanied him on his outdoor painting expeditions.

They would often set up their easels side-by-side, tackling the same motifs – haystacks shimmering in the sun, poplar trees lining the Epte River, the gentle flow of the Seine, or the burgeoning gardens at Giverny. This practice allowed Blanche to learn directly through imitation and adaptation, receiving Monet's advice and critiques in real-time. Art historians note the striking similarity between some of her works from this period and Monet's, a testament to her close study and his pervasive influence.

However, her role was not merely imitative. Contemporary accounts and Monet's own correspondence suggest he valued her presence and her eye. She became an indispensable part of his working process, a trusted companion who understood his artistic aims. This close collaboration provided Blanche with an artistic education few could dream of, immersing her completely in the Impressionist method of capturing transient moments and the subjective experience of seeing.

Her dedication was profound. She embraced the Impressionist ethos wholeheartedly, focusing on landscape painting and the effects of light. Unlike some contemporaries who might have sought more formal academic training, Blanche's education was practical, observational, and deeply rooted in the landscape that surrounded her daily life in Giverny.

Life and Art in Giverny

The move to Giverny in 1883 was transformative for everyone involved. For Monet, it provided a stable home and the inspiration for his most famous late works. For Blanche, it offered a permanent landscape subject and a central place within a growing artistic community. The house and, more significantly, the gardens that Monet meticulously cultivated became primary subjects for her as well.

Blanche painted the Clos Normand, the flower garden in front of the house, with its vibrant tangle of roses, poppies, and irises. She also depicted the Water Garden, established later across the road, with its iconic Japanese bridge, weeping willows, and, of course, the water lilies that obsessed Monet. Her paintings of Giverny capture the beauty and tranquility of the place, often featuring the familiar motifs but rendered with her own sensibility.

Her artistic output during the 1880s and early 1890s was significant. She worked diligently, producing numerous landscapes that showcased her understanding of Impressionist principles. Her brushwork was often lively and textured, her palette bright, reflecting the influence of Monet but gradually developing its own characteristics. Some critics have noted a lighter, perhaps more delicate touch in her work compared to the sometimes rugged intensity of Monet's canvases.

Giverny wasn't just a place to paint; it was the center of her social and familial world. After Monet's first wife Camille died in 1879, Alice Hoschedé took over the running of the household. Following Ernest Hoschedé's death in 1891, Monet and Alice married in 1892, formalizing the blended family structure. Blanche was thus officially Monet's stepdaughter.

Marriage to Jean Monet

The intricate family ties deepened further in 1897 when Blanche married Claude Monet's eldest son, Jean Monet. This union made her not only Monet's stepdaughter but also his daughter-in-law. Jean, who pursued interests in chemistry, and Blanche settled in Rouen and later Beaumont-le-Roger, maintaining close ties with Giverny.

The marriage appears to have been a stable one, though sources indicate they did not have children. During this period, Blanche continued to paint, though perhaps less prolifically than in her earlier years as Monet's direct assistant. Her subjects expanded to include the landscapes around her new homes, but Giverny remained a frequent touchstone, both personally and artistically. She often returned to paint alongside her stepfather, particularly during visits.

Tragically, Jean Monet suffered from ill health and died relatively young in 1914. His death marked another turning point for Blanche. Following the loss of her husband, and with Monet himself aging and deeply affected by the earlier death of Alice in 1911, Blanche made the decision to return permanently to Giverny.

Artistic Style, Subjects, and Development

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet was fundamentally an Impressionist landscape painter. Her primary education came directly from Monet, and her work consistently reflects the core tenets of the movement: painting outdoors, capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, using broken brushwork, and employing a bright, often pure color palette.

Her most frequent subjects were the landscapes she knew intimately: the fields, rivers, and gardens of Giverny and the surrounding Normandy region. She painted haystacks (meules), a subject famously explored by Monet, but her interpretations often possess a distinct character. Poplar trees lining the Epte River were another recurring motif, echoing Monet's series but again, viewed through her own lens. She captured the changing seasons, producing vibrant spring scenes, sun-drenched summer landscapes, autumnal views, and notably, atmospheric snow scenes (effets de neige).

While the influence of Monet is undeniable, particularly in her choice of subjects and compositional structures, Blanche developed an independent artistic personality. Her style is sometimes described as being softer or more decorative than Monet's, with a fluid and confident brushstroke. She excelled at capturing the lushness of vegetation and the specific quality of light in the Ile-de-France region. Art historian and curator Philippe Piguet has noted her "independent and firm style."

Unlike Mary Cassatt or Berthe Morisot, who often focused on domestic interiors and figures, Blanche remained predominantly a landscape painter, aligning her more closely with Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley in terms of subject matter. Her commitment to plein air painting was unwavering throughout her career. She sought to translate her direct sensory experience of nature onto the canvas, embodying the Impressionist quest for perceptual truth.

Representative Works

Identifying specific "masterpieces" for Blanche Hoschedé-Monet is challenging, as many of her works remain in private collections and her oeuvre hasn't received the same exhaustive cataloging as Monet's. However, several notable works and recurring themes give a sense of her artistic achievements:

Haystack near Giverny (various versions): Like Monet, she painted haystacks under different light conditions. One such Meule de Foin was noted in auction records, demonstrating her engagement with this iconic Impressionist subject.

Poplars on the Bank of the Epte (various versions): Another subject shared with Monet, her paintings of these trees showcase her ability to capture reflections in water and the vertical rhythm of the landscape.

Monet's Garden at Giverny (numerous works): She painted many views of both the Clos Normand and the Water Garden, including depictions of the flowerbeds, the Japanese bridge, and the water lily pond. Titles like Le Printemps (Le bassin aux nymphéas à Giverny) (Spring (The Water Lily Pond at Giverny), 1928), held at the Musée Marmottan Monet, exemplify this focus. Jardin des Glaïeuls, Giverny (Gladiolus Garden, Giverny, 1928) is another example from the Marmottan.

Snow Scene / Paysage de neige (e.g., the 1910 version in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen): Blanche created sensitive renderings of the landscape under snow, capturing the subtle blues and pinks of winter light.

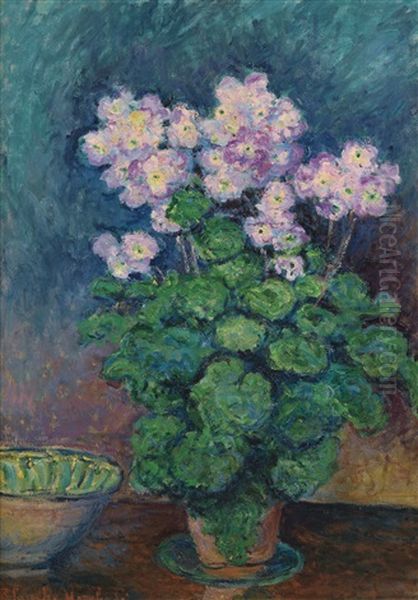

PRIMEVÈRES (Primroses): Mentioned in the provided text as an oil painting (65 x 46 cm) exhibited and valued, suggesting her skill with floral subjects within a landscape context.

Monet's Dining Room at Giverny: A departure from pure landscape, this work (mentioned as being in a private collection) shows her ability to handle interior scenes, likely depicting the distinctive yellow dining room at Giverny, famous for its collection of Japanese prints.

View of Rouen: During her time living there with Jean, she painted views of the city, known for its cathedral famously painted by Monet.

These examples highlight her consistent engagement with Impressionist motifs and techniques, particularly those centered around Giverny and its environs.

Interactions within the Impressionist Circle and Beyond

Blanche's life placed her in direct contact with many key figures of the Impressionist movement and the wider art world. Her most significant relationship was, of course, with Claude Monet. Beyond being his student and assistant, she was a constant presence, a model in some of his early Giverny paintings (like Woman with a Parasol, though this usually depicts Suzanne Hoschedé, Blanche's sister), and later, his devoted caretaker.

Through her family's initial patronage and later through Monet, she knew other founding Impressionists. She reportedly visited the studio of Edouard Manet in her youth, absorbing the atmosphere of his influential, pre-Impressionist realism and modern subjects. Manet himself painted portraits of Alice Hoschedé. Blanche also likely encountered Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who were part of Monet's circle and beneficiaries of Ernest Hoschedé's early support.

Her connection to Berthe Morisot, the preeminent female Impressionist, is less documented but probable, given Morisot's close ties with Manet (her brother-in-law) and her participation in the Impressionist exhibitions. As a fellow female painter navigating a male-dominated field, any interaction would have been significant.

The American Impressionists who flocked to Giverny from the late 1880s onwards formed another important part of Blanche's social and artistic network. She had direct interactions with painters like John Leslie Breck. Sources suggest a romantic attachment between them, which Monet reportedly discouraged, perhaps wanting to keep Blanche within the family orbit. Breck was a key figure in establishing the Giverny art colony.

She also painted alongside Theodore Earl Butler, another prominent American Impressionist who became even more closely tied to the family when he married Blanche's sister, Suzanne Hoschedé, in 1892 (and after Suzanne's death, married her younger sister, Marthe). Other American artists working in Giverny whom Blanche would have known included Theodore Robinson, Willard Metcalf, Louis Ritter, and later figures like Frederick Carl Frieseke.

Beyond the painters, she knew influential figures connected to Monet, such as the writer Octave Mirbeau, the art dealers Paul Durand-Ruel and Georges Petit, and the statesman Georges Clemenceau. Clemenceau was a fierce defender of Monet and a frequent visitor to Giverny in Monet's later years, a period when Blanche was managing the household. She is known to have painted alongside Clemenceau in the Giverny garden. This network placed Blanche at the crossroads of artistic and intellectual life in France.

The Giverny Art Colony: A Central Figure

While Monet famously kept a certain distance from the burgeoning art colony that grew up around him in Giverny, Blanche likely served as a more accessible link. As Monet's stepdaughter and assistant, living at the heart of the place that drew so many artists, she was a natural point of contact and interaction.

The colony, primarily composed of American painters eager to learn from the master of Impressionism, transformed the small village into an international artistic hub. Artists like Robinson, Breck, Butler, Metcalf, and Frieseke adapted Impressionist techniques to their own sensibilities, often focusing on the local landscape and figurative scenes within it. Blanche, as a native Frenchwoman, a skilled Impressionist painter herself, and a member of Monet's inner circle, occupied a unique position.

She participated in the artistic life of the colony, painting the same landscapes and potentially exchanging ideas with the visiting artists. Her presence and her work contributed to the vibrant creative atmosphere of Giverny during its peak years as an art center. She embodied the continuity of the Impressionist tradition within the very landscape that had become synonymous with the movement.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Despite her talent and proximity to Monet, Blanche Hoschedé-Monet did not achieve widespread fame during her lifetime. This was partly due to the immense shadow cast by Monet and the general difficulties faced by female artists in gaining recognition and establishing independent careers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, she did exhibit her work regularly. She participated in the Salon des Indépendants in Paris, a key venue for avant-garde artists, starting in 1905. She also showed her paintings at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Rouennais in Rouen, reflecting her ties to that city during her marriage to Jean. Later in her career, she had solo exhibitions at respected Parisian galleries, including Galerie Bernheim-Jeune (1931) and Galerie Zak (1947, posthumously). A retrospective exhibition was held at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen in 1954, and another significant show took place at the Musée Municipal A.G. Poulain in Vernon (near Giverny) in 1991.

While contemporary critical reviews were often positive, acknowledging her skill and adherence to Impressionist principles, she was frequently discussed primarily in relation to Monet. Her work was sometimes praised for its "feminine" delicacy, a common trope used when discussing female artists of the period, which could subtly diminish the assessment of its strength and originality.

The fact that many of her works went directly into private collections, rather than public institutions, also limited her visibility. It is only in more recent decades, with increased scholarly interest in female artists and figures peripheral to the main Impressionist narrative, that Blanche Hoschedé-Monet's contributions have begun to be more fully appreciated. Auction results for her works, such as the sale of a Haystack painting, indicate a growing market recognition of her talent.

Later Years: Guardian of the Flame

The period following Alice Monet's death in 1911 was difficult for Claude Monet. The death of his son Jean in 1914 added to his grief. It was during this time that Blanche returned to Giverny to live permanently and care for her aging stepfather. This became her primary role for the last twelve years of Monet's life.

She managed the household, oversaw the gardens, and provided essential emotional and practical support to Monet as he grappled with failing eyesight due to cataracts and embarked on his final, monumental project: the Grandes Décorations, the large water lily panels destined for the Orangerie museum in Paris. Accounts from visitors during this period often mention Blanche's devoted presence, her efforts to maintain the Giverny sanctuary, and her role as intermediary between the increasingly reclusive Monet and the outside world.

Georges Clemenceau, a close friend during these years, referred to Blanche as Monet's "Blue Angel," highlighting her protective and supportive role. She assisted Monet in the studio, helped him navigate his visual impairment (before and after his cataract surgeries), and ensured the smooth running of the Giverny estate, which was both his home and his artistic laboratory. Her dedication allowed Monet to continue working on his ambitious final project until his death.

After Monet died on December 5, 1926, Blanche remained at Giverny. She inherited the property along with Monet's other surviving son, Michel. Blanche took on the responsibility of preserving the house and, crucially, the gardens, which had fallen into disrepair during the war years and Monet's final illness. She worked to maintain them as best she could, safeguarding the legacy that was so intertwined with her own life.

Legacy and Collections

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet died in 1947 and is buried in the Monet family vault in the Giverny church cemetery, alongside Claude Monet, Alice Hoschedé, Jean Monet, and other family members. Her legacy is complex. As an artist, she was a dedicated and talented Impressionist who created a substantial body of work reflecting her deep connection to the Normandy landscape, particularly Giverny. Her paintings offer a valuable perspective on Impressionism, demonstrating both the influence of Monet and the development of a personal style.

Her role as Monet's student, assistant, and caretaker was also crucial. Her support, especially in his later years, was instrumental in enabling him to complete his final masterpieces. She served as a vital link between Monet and the world, and after his death, she became the initial guardian of the Giverny estate.

Today, her works are held in several public collections, most notably:

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris: This museum, holding the world's largest collection of Monet's works (thanks largely to a bequest from his son Michel), also possesses several paintings by Blanche, including views of the Giverny garden.

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen: Holds works including her Paysage de neige (1910).

Musée de Vernon (Musée Alphonse-Georges Poulain): Located near Giverny, this museum has actively collected and exhibited works by artists associated with the Giverny colony, including Blanche.

Many of her paintings remain in private hands, occasionally appearing at auction where they command respectable prices, reflecting a renewed appreciation for her artistic merit. While she may never escape the comparison with her monumental stepfather, Blanche Hoschedé-Monet is increasingly recognized as a significant painter in her own right, a dedicated Impressionist whose life and art provide invaluable insights into the movement and its most iconic location.

Conclusion: More Than a Reflection

Blanche Hoschedé-Monet's life story is one of deep immersion in the world of Impressionism. Born into a family that patronized the movement, raised in Claude Monet's household, trained at his side, and eventually becoming part of his immediate family, her connection was unparalleled. She translated this unique experience into a body of work that faithfully adheres to Impressionist principles while developing its own quiet authority. Her landscapes of Giverny and Normandy are sensitive, skilled, and imbued with a genuine love for the motifs she painted.

Beyond her own canvases, her role in supporting Claude Monet, particularly during the challenging final years of his life as he worked on the monumental Grandes Décorations, cannot be overstated. She was a companion, assistant, and caretaker, ensuring the continuation of his work and the preservation of his Giverny haven. While historical narratives have often positioned her solely in relation to Monet, a closer look reveals an artist of genuine talent and a figure of considerable importance within the Impressionist circle and the legacy of Giverny. Her art and her life offer a compelling testament to the enduring power of the Impressionist vision, seen through the eyes of one of its most intimate participants.