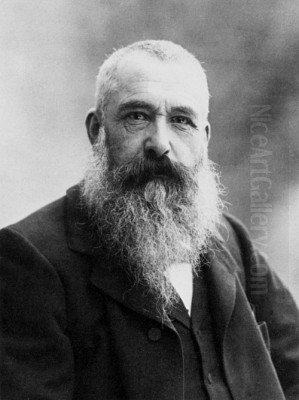

Claude Monet, born Oscar-Claude Monet on November 14, 1840, in Paris, stands as one of the most pivotal figures in the history of Western art. As a founder and the most unwavering advocate of the Impressionist movement, his life's work was dedicated to capturing the fleeting effects of light and color in the natural world. His radical approach to painting, emphasizing perception and momentary sensation over academic convention, not only defined Impressionism but also laid crucial groundwork for the development of modern art. Monet's relentless exploration of visual phenomena, particularly through his iconic series paintings and his beloved garden at Giverny, resulted in a body of work that continues to enchant and inspire audiences worldwide. He passed away on December 5, 1926, leaving behind a legacy built on light, color, and an enduring connection to nature.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Oscar-Claude Monet was the second son of Claude Adolphe Monet, a wholesaler and ship chandler, and Louise Justine Aubrée Monet, a singer. Both his parents were Parisians by birth. When Monet was about five years old, in approximately 1845, the family relocated from the bustling capital to the port city of Le Havre in Normandy. This move proved formative, immersing the young Monet in the coastal landscapes and variable weather conditions that would later dominate his art. His childhood was spent near the sea, an environment that undoubtedly sharpened his awareness of changing light and atmosphere.

His father envisioned a practical future for his son, hoping Oscar-Claude would eventually join the family's grocery and shipping business. However, Monet displayed an early and pronounced inclination towards art. He initially gained local recognition not for landscape painting, but for his skillful and often humorous charcoal caricatures of Le Havre's citizens. By the age of 15, he had developed a modest reputation and was selling these drawings, earning enough money, according to some accounts, to fund his aspirations beyond the confines of Le Havre.

Despite his father's preference for a commercial career, Monet found crucial support within his family. His mother, Louise, was reportedly supportive of his artistic leanings before her untimely death in 1857. Following this loss, Monet's aunt, Marie-Jeanne Lecadre, an amateur painter herself, took him under her wing. She played a significant role in encouraging his artistic pursuits and likely helped persuade his father to allow him to pursue art more seriously. It was during these formative years in Le Havre that Monet's path began to diverge decisively from the business world towards the life of an artist.

The Influence of Mentors and Peers

A pivotal encounter in Monet's early development occurred around 1858 when he met Eugène Boudin. Boudin was an established landscape painter known for his marine scenes and his practice of painting outdoors, or en plein air. Initially hesitant, Monet was eventually persuaded by Boudin to abandon caricature and try landscape painting directly from nature. Boudin taught him the importance of capturing the immediacy of a scene and the effects of natural light. This mentorship was transformative, opening Monet's eyes to the possibilities of painting the Normandy coast and skies with a newfound freshness and directness. He later acknowledged Boudin's crucial influence, stating, "If I have become a painter, it is entirely due to Eugène Boudin."

Another important early influence was the Dutch landscape painter Johan Barthold Jongkind. Monet met Jongkind shortly after his encounter with Boudin. Jongkind's work, characterized by its free brushwork and keen observation of light on water, further reinforced the lessons Monet was learning from Boudin. Monet admired Jongkind's ability to capture the essence of a scene with apparent spontaneity, even though Jongkind often finished his works in the studio based on outdoor sketches. The combined influence of Boudin and Jongkind solidified Monet's commitment to landscape painting and the study of light.

In 1859, with savings from his caricatures and support from his aunt, Monet moved to Paris to formally pursue his art education. He enrolled at the Académie Suisse, an informal studio where artists could draw from a live model without rigid instruction. There, he met Camille Pissarro, another artist who would become a central figure in Impressionism. Pissarro, slightly older and more experienced, shared Monet's interest in moving beyond academic constraints. Monet's time in Paris was interrupted by military service in Algeria (1861-1862), which was cut short by illness. Upon his return, financed by his aunt buying him out of further service, he entered the studio of Charles Gleyre.

Gleyre's studio, though more traditional, became an unexpected crucible for Impressionism. It was here, between 1862 and 1864, that Monet formed close friendships with fellow students Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille. This group shared a dissatisfaction with Gleyre's academic approach and a growing interest in painting contemporary life and landscapes directly observed. They often left the studio to paint together outdoors, particularly in the Forest of Fontainebleau, experimenting with techniques to capture the transient effects of sunlight filtering through leaves or reflecting on water. These early collaborations and shared ideals were fundamental in shaping the core group that would later launch the Impressionist movement.

Forging a New Vision: The Birth of Impressionism

Throughout the 1860s, Monet and his circle struggled for recognition within the established art world, dominated by the conservative French Academy and its official exhibition, the Salon de Paris. While Monet achieved occasional success, having two marine paintings accepted by the Salon in 1865, he and his friends faced frequent rejections. Their developing style—characterized by looser brushwork, a brighter palette, and a focus on capturing the fleeting visual sensations of a moment—clashed with the polished finish and historical or mythological subjects favored by the Academy. Figures like Gustave Courbet, a leader of the Realist movement, and Édouard Manet, whose work scandalized the Salon with its modern subjects and bold technique (e.g., Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, Olympia), served as important precursors, challenging the status quo and inspiring younger artists like Monet.

The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) caused a temporary dispersal of the group. Monet sought refuge in London with Pissarro, where they were exposed to the works of English landscape painters J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, whose atmospheric effects and free handling of paint likely resonated with their own explorations. After a period in the Netherlands, Monet returned to France and settled in Argenteuil, a suburb northwest of Paris on the Seine River. The years in Argenteuil (1871-1878) were incredibly productive and marked a key period in the consolidation of the Impressionist style. Here, often joined by Renoir, Sisley, and sometimes Manet and Gustave Caillebotte, Monet painted numerous scenes of leisure activities, river landscapes, and his own garden, further refining his techniques for rendering light and reflection on water.

Frustrated by continued resistance from the Salon, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and others decided to organize their own independent exhibition. This groundbreaking event took place in April 1874 in the former studio of the photographer Nadar. Among the works Monet displayed was a painting depicting the harbor of Le Havre in the early morning mist, titled Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise). Reviewing the exhibition, the critic Louis Leroy, writing for the satirical journal Le Charivari, seized upon Monet's title to mockingly label the entire group "Impressionists." While intended derisively, the name stuck, perfectly encapsulating the artists' shared aim of conveying their immediate visual impressions rather than detailed, objective reality. This exhibition, though financially unsuccessful and critically controversial, marked the public debut of Impressionism as a distinct artistic movement.

Life's Canvas: Personal Joys and Sorrows

Monet's personal life was deeply intertwined with his artistic career, marked by both profound connections and significant hardships. In 1865, he met Camille-Léonie Doncieux, who quickly became his model, muse, and companion. She featured prominently in several of his major early works, including the ambitious, large-scale Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (left unfinished) and the critically acclaimed Woman in the Green Dress (1866). Their first son, Jean, was born in 1867. Despite family opposition, particularly from his father who disapproved of the relationship, Claude and Camille married in 1870, just before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War.

The early years of their marriage were often plagued by severe financial difficulties. Monet struggled to sell his paintings, and the family frequently lived in poverty, relying on support from friends like Bazille (until his death in the war) and later the collector and fellow painter Gustave Caillebotte. Despite these challenges, the paintings from the Argenteuil period often depict idyllic scenes of domestic life and leisure, featuring Camille and Jean in sunlit gardens or boating on the Seine (e.g., Woman with a Parasol - Madame Monet and Her Son, 1875). These works radiate a sense of warmth and intimacy, capturing moments of personal happiness amidst precarious circumstances.

Tragedy struck the family in the late 1870s. Camille gave birth to their second son, Michel, in March 1878. However, her health, possibly weakened by poverty and multiple pregnancies, rapidly declined. She was diagnosed with what was likely uterine cancer or tuberculosis. During this period, the Monets were living in Vétheuil, sharing a house with Ernest Hoschedé, a wealthy department store magnate and art patron, his wife Alice, and their six children. Hoschedé's bankruptcy had forced this unusual living arrangement. Alice Hoschedé nursed Camille through her final illness.

Camille died on September 5, 1879, at the age of 32. In a poignant and somewhat haunting act, Monet painted his wife on her deathbed (Camille Monet on Her Deathbed, 1879), compelled, as he later described, to capture the subtle gradations of color appearing on her face in death. This period marked a somber turn in his work, with paintings often reflecting the harsh winter landscapes around Vétheuil. Following Camille's death, Alice Hoschedé remained to care for Monet's two sons alongside her own children. A complex relationship developed between Claude and Alice, and after Ernest Hoschedé's death in 1891, they married in 1892. Alice would manage the household and Monet's affairs until her own death in 1911.

Giverny: A Garden Sanctuary and Open-Air Studio

In 1883, seeking a more permanent and tranquil setting, Monet rented a house with a large garden and orchard in the village of Giverny, located in Normandy about fifty miles west of Paris. This move marked a turning point in his life and art. Initially renting, he was able to purchase the property in 1890 as his financial situation improved, thanks largely to the efforts of his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who had begun successfully promoting Impressionist works in France and America. Giverny would remain Monet's home, sanctuary, and primary source of inspiration for the rest of his life.

Over the next four decades, Monet poured immense energy and resources into transforming the Giverny property. He redesigned the existing flower garden in front of the house, known as the Clos Normand, arranging flowers by color blocks to create vibrant palettes that changed with the seasons. He cultivated a vast array of common and rare flowers, creating a living, breathing composition that he would translate onto canvas. This garden itself became a major subject, depicted in numerous paintings filled with irises, poppies, roses, and sunflowers under varying light conditions.

In 1893, Monet acquired an adjacent piece of land across a local road and railway line. With permission from the authorities, he diverted a small stream, the Ru, to create a water garden. This garden was inspired by the Japanese prints he avidly collected (artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige were among his favorites). He constructed an arched, Japanese-style footbridge (painted green, not the red often depicted in reproductions) and planted the pond with exotic water lilies (Nymphéas). Willows, bamboo, and other moisture-loving plants lined the banks, creating an enclosed, contemplative world distinct from the more formal Clos Normand.

Giverny was not just a home but an extension of Monet's artistic practice. The gardens were conceived and cultivated with a painter's eye, designed to offer constantly shifting perspectives, reflections, and color harmonies. He had several studios on the property, including one attached to the house (later used as a sitting room) and a larger, purpose-built studio constructed later for his monumental works. Famously, he also used a small boat fitted out as a floating studio, allowing him to paint directly on the water, capturing the interplay of light, water, and reflections from a unique vantage point. The Giverny gardens became Monet's ultimate motif, a self-contained universe where he could endlessly explore his core artistic preoccupations.

The Power of Series: Capturing Fleeting Moments

One of Monet's most significant contributions to art was his development and extensive use of series painting. While artists before him had occasionally painted the same subject multiple times, Monet elevated this practice into a systematic method for exploring the effects of changing light, atmosphere, and season on a single motif. He understood that the appearance of an object—its color, form, and mood—was not fixed but constantly altered by the conditions under which it was viewed. By painting the same subject repeatedly, sometimes working on multiple canvases simultaneously as the light changed throughout the day, he sought to capture these ephemeral nuances.

His first major series, begun in the late 1880s and exhibited to great acclaim in 1891, depicted haystacks (or more accurately, grainstacks) in a field near his Giverny home. The Haystacks series (Les Meules) comprises around twenty-five canvases showing the stacks at different times of day, in various seasons, and under diverse weather conditions—from bright summer sun to frost-covered winter mornings and hazy sunsets. The stacks themselves are simple, almost abstract forms, serving primarily as surfaces upon which light and color could play. The series demonstrated Monet's mastery in rendering subtle atmospheric effects and the way light could dissolve or solidify form.

Following the success of the Haystacks, Monet embarked on several other important series in the 1890s. The Poplars series (Les Peupliers, 1891) captured a line of trees along the Epte River near Giverny, focusing on the interplay of vertical forms, reflections in the water, and the decorative, sinuous lines of the trees against the sky. Perhaps his most famous series from this period is the Rouen Cathedral sequence (1892-1894). Working from a room opposite the cathedral's west facade, Monet produced nearly thirty canvases depicting the intricate Gothic stonework under dramatically different light conditions, from the cool blues and violets of early morning to the warm oranges and golds of sunset. The cathedral becomes less a solid architectural structure and more a shimmering screen reflecting the ever-changing atmosphere.

Monet also applied the series approach during his travels. Several trips to London between 1899 and 1904 resulted in extensive series focusing on the Waterloo Bridge, Charing Cross Bridge, and the Houses of Parliament. These works masterfully capture the effects of London's characteristic fog and industrial haze, dissolving solid structures into ethereal visions of color and light. A trip to Venice in 1908 yielded another series, depicting iconic landmarks like the Doge's Palace and the Grand Canal bathed in the unique Mediterranean light. Through his series paintings, Monet pushed the boundaries of Impressionism, moving towards a more abstract concern with color and light as subjects in themselves.

The Grand Culmination: The Water Lilies (Nymphéas)

In the final decades of his life, Monet's artistic focus narrowed almost exclusively to the water garden he had meticulously created at Giverny. The water lilies, the Japanese bridge, the weeping willows, and the reflections on the pond's surface became an obsession, resulting in his most ambitious and immersive body of work: the Nymphéas or Water Lilies series. This vast project would occupy him from the late 1890s until his death in 1926, yielding approximately 250 paintings.

Initially, the Water Lilies paintings included elements like the Japanese bridge or the banks of the pond, providing spatial reference points. However, as the series progressed, Monet increasingly zoomed in on the water's surface itself. The horizon line disappeared, and the paintings became immersive fields of color and light, capturing the interplay between the floating lily pads, the blossoms, the reflections of the sky and clouds, and the unseen depths of the water. The brushwork became looser and more expressive, sometimes bordering on abstraction, as Monet sought to convey the total sensory experience of being enveloped by the garden.

This late work coincided with personal loss and physical challenges. His second wife, Alice, died in 1911, followed by his eldest son, Jean, in 1914. Compounding these sorrows was Monet's deteriorating eyesight due to cataracts, diagnosed definitively around 1912. His vision became increasingly blurred, and his perception of color was significantly altered—blues tended to disappear, while reds and yellows became more dominant, a shift sometimes visible in the palettes of his later canvases. Despite this profound challenge, Monet resisted cataract surgery for years, fearing it would irrevocably change his vision. He continued to paint, relying on his memory, his intimate knowledge of his motifs, and possibly adapting his technique to his altered perception.

During World War I, Monet conceived his grandest project: the Grandes Décorations, a series of monumental water lily murals intended as a gift to the French nation, a "monument to peace." He envisioned an environment where viewers could be completely surrounded by the tranquil beauty of his water garden. Encouraged by his friend, the statesman Georges Clemenceau, Monet worked tirelessly on these enormous canvases in a specially constructed large studio at Giverny. He finally underwent cataract surgery in 1923, which partially restored his vision but also caused difficulties as he readjusted. He continued refining the murals until his death. The Grandes Décorations were installed posthumously according to his wishes in two oval rooms in the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris, opening to the public in 1927. They remain one of the most profound achievements of his career, a testament to his enduring vision and his ability to transform personal observation into a universal experience of nature and light.

Monet and His Contemporaries

Claude Monet did not create Impressionism in isolation. He was part of a dynamic network of artists who shared ideas, exhibited together, and mutually influenced one another, even while maintaining distinct artistic personalities. Understanding Monet requires acknowledging these vital connections.

His closest Impressionist colleagues were Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley, whom he met in Gleyre's studio alongside Frédéric Bazille. Renoir shared Monet's interest in capturing light and modern life, though Renoir often focused more on figures and portraiture, employing a softer, more feathery brushstroke. Sisley remained perhaps the most "pure" landscape painter among the core Impressionists, focusing on the subtle atmospheric effects of the Île-de-France region with a delicate sensitivity. Camille Pissarro, older than Monet, served as a mentor figure to many younger artists, including Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin. Pissarro's work encompassed landscapes and rural scenes, and he was the only artist to exhibit in all eight Impressionist exhibitions (1874-1886).

Edgar Degas, another key figure who exhibited with the group, differed significantly in his approach. Degas preferred scenes of modern urban life—ballet dancers, cafés, racetracks—and emphasized drawing and composition over the plein air study of light that preoccupied Monet. He famously quipped that Monet was "only an eye, but my God, what an eye!" Édouard Manet, though older and often considered a precursor rather than a full member, was deeply admired by Monet and his friends. Manet never exhibited with the Impressionists but maintained close ties, and his bold style and modern subjects were highly influential.

Other important figures associated with the movement include Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, two prominent female Impressionists. Morisot, Manet's sister-in-law, created intimate scenes of domestic life and landscapes with a light, fluid touch. Cassatt, an American expatriate and close friend of Degas, focused on portraits, particularly mothers and children, combining strong composition with Impressionist light and color. Gustave Caillebotte was not only an Impressionist painter known for his unique perspectives on urban scenes but also a crucial patron who supported his fellow artists financially and bequeathed his remarkable collection (including many works by Monet, Renoir, Degas, and others) to the French state. Monet's early mentors, Eugène Boudin and Johan Barthold Jongkind, while not strictly Impressionists, were vital in setting him on his path. Even artists who moved away from Impressionism, like Paul Cézanne, initially exhibited with the group and shared early concerns before forging their own revolutionary paths towards Post-Impressionism. The sculptor Auguste Rodin was also a contemporary and friend, sharing an interest in capturing movement and the effects of light on surfaces.

Monet's Enduring Legacy

Claude Monet's death in 1926 marked the end of a long and extraordinarily influential career. His impact on the course of art history was immediate and profound. As the driving force behind Impressionism, he fundamentally changed the way artists perceived and represented the world. His insistence on capturing subjective visual sensation over objective reality, his innovative techniques for rendering light and color using broken brushwork and complementary colors, and his dedication to painting modern life and landscapes en plein air dismantled centuries of academic tradition.

Impressionism itself, largely defined by Monet's vision, became the first truly modern art movement, paving the way for subsequent avant-gardes. His work directly influenced the Post-Impressionists. Vincent van Gogh admired his use of color, while Georges Seurat developed Pointillism partly in response to Impressionist color theory. Paul Cézanne, though moving towards a more structured representation of form, built upon Impressionist foundations. The Fauvist movement, led by Henri Matisse, with its emphasis on expressive, non-naturalistic color, owes a debt to the liberation of color initiated by Monet and his contemporaries.

Beyond these direct lineages, Monet's late work, particularly the near-abstract Water Lilies, had a delayed but significant impact on twentieth-century art. The large, immersive canvases, with their all-over compositions and focus on color and surface, resonated with the Abstract Expressionist painters in America in the 1940s and 50s. Artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Joan Mitchell found inspiration in the scale, freedom, and atmospheric quality of Monet's late masterpieces. The Orangerie murals, in particular, came to be seen as precursors to environmental art and installation work.

Today, Claude Monet remains one of the most beloved and recognizable artists in the world. His paintings command enormous prices at auction, and exhibitions of his work consistently draw huge crowds. His home and gardens at Giverny have been restored and are a major tourist destination, allowing visitors to step into the world that inspired so many of his masterpieces. More than just a painter of pretty pictures, Monet was a radical innovator whose relentless pursuit of capturing the fleeting moments of visual experience opened up new possibilities for painting and forever changed the way we see art.

Conclusion: An Eye That Changed Art

Claude Monet's journey from a young caricaturist in Le Havre to the revered master of Giverny is a story of unwavering dedication to a singular artistic vision. He pursued the ephemeral qualities of light and atmosphere with unparalleled tenacity, developing a visual language that defined Impressionism and irrevocably altered the landscape of modern art. Through his commitment to painting outdoors, his revolutionary use of color and brushwork, and his pioneering development of series painting, he taught the world to see the familiar—a haystack, a cathedral, a pond—in entirely new ways. His work invites us to pause and observe the constant flux of the natural world, finding beauty in the most transient effects of light on water or stone. Monet was, as Cézanne reportedly said, "the most prodigious eye since painting began," an eye whose perceptions translated onto canvas continue to resonate with profound beauty and artistic innovation. His legacy is not just in the stunning canvases he left behind, but in the fundamental shift in artistic perception that he helped to engineer.