Boris Mikhailovich Kustodiev stands as a significant and beloved figure in the landscape of early 20th-century Russian art. Active during a period of immense social upheaval and artistic innovation, Kustodiev carved a unique niche for himself, becoming renowned for his vibrant, joyful depictions of Russian provincial life, traditional festivals, and the burgeoning merchant class. Despite facing personal hardships, including debilitating illness, his work consistently radiates an infectious optimism and a deep affection for his homeland's culture and people. As a painter, graphic artist, illustrator, and stage designer, his multifaceted talent left an indelible mark on Russian art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Boris Kustodiev was born on March 7, 1878, in Astrakhan, a bustling port city on the Volga River delta. His father, Mikhail Lukich Kustodiev, was a professor of philosophy, history of literature, and logic at the local theological seminary. However, his father passed away young, leaving the financial and educational responsibilities of the family primarily on the shoulders of Boris's mother, Ekaterina Prokhorovna. This early exposure to the challenges of life perhaps fostered a resilience that would mark his later years.

The vibrant atmosphere of the Volga region, with its diverse population and rich traditions, undoubtedly left a lasting impression on the young Kustodiev. His artistic inclinations emerged early. A pivotal moment occurred when he was around eleven years old; a travelling exhibition of the Peredvizhniki (the "Wanderers") visited Astrakhan. Seeing the works of these prominent Russian realists ignited a passion within him, solidifying his ambition to become an artist. The Peredvizhniki, including masters like Ilya Repin and Vasily Surikov, focused on depicting the lives of ordinary Russians and critiquing social inequalities, an ethos that resonated with Kustodiev, though his own path would lead towards a more celebratory style.

He began his formal art education under Pavel Vlasov, a local artist who had studied at the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. Recognizing Kustodiev's potential, Vlasov encouraged him to pursue further studies in the capital. In 1896, Kustodiev successfully entered the Imperial Academy of Arts, a crucial step in his development.

Studies under Repin and Early Success

At the Imperial Academy, Kustodiev initially studied in the general classes before joining the studio of the renowned master Ilya Repin in 1898. Repin was arguably the most famous Russian artist of his time, a leading figure of the Peredvizhniki movement known for his powerful historical paintings and insightful portraits. Studying under Repin provided Kustodiev with a strong foundation in realist technique, draftsmanship, and psychological portraiture.

Repin recognized Kustodiev's talent, particularly his skill with color and his ability to capture character. He entrusted Kustodiev, along with another student, Ivan Kulikov, to assist him with a major state commission: the monumental painting Ceremonial Session of the State Council on May 7, 1901, Marking the Centenary of its Foundation (completed 1903). Kustodiev was responsible for painting a significant portion of the figures on the right side of the canvas. This collaboration was a testament to his abilities and provided invaluable experience working on a large-scale, complex composition.

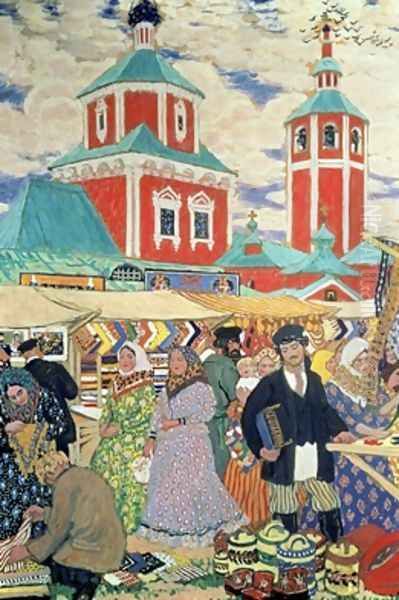

During his studies, Kustodiev also began developing his own thematic interests. He travelled during summers, often returning to the Volga region, sketching scenes of provincial life, markets, and local festivities. His diploma work, At the Bazaar (1903), already hinted at the direction his art would take, showcasing his fascination with the bustling energy and colorful characters of Russian marketplaces. He graduated from the Academy with a gold medal and a scholarship for travel abroad.

Travels and the Formation of a Style

The scholarship allowed Kustodiev to travel to France and Spain in 1904. He studied the works of the Old Masters in the Louvre and the Prado, paying particular attention to the Spanish painters like Velázquez for their use of color and light. He also encountered contemporary European art movements, including Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, which likely influenced his already vibrant palette. However, unlike many Russian artists who became deeply immersed in Western European styles, Kustodiev's focus remained firmly rooted in Russian themes.

Upon returning to Russia, Kustodiev became associated with the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement, officially joining the group in 1910. This influential artistic circle, led by figures like Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, and Sergei Diaghilev, advocated for aestheticism, artistic synthesis, and a revival of interest in 18th-century Russian art and folk traditions. While distinct from the critical realism of the Peredvizhniki, Mir Iskusstva shared an interest in national identity, albeit often expressed through more stylized and decorative means. Other prominent members included Konstantin Somov, Nicholas Roerich, and Mstislav Dobuzhinsky.

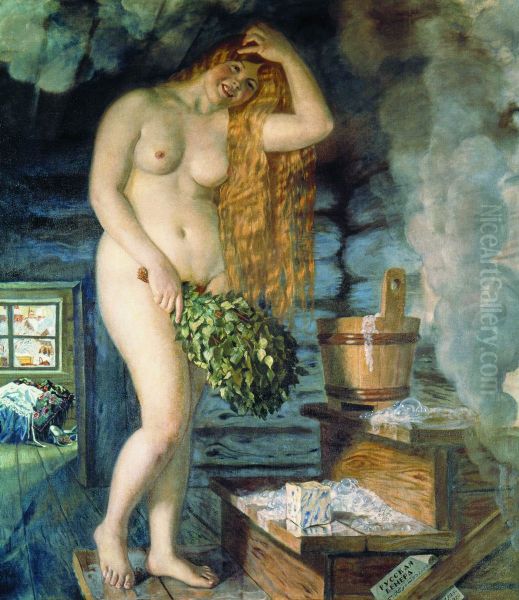

Kustodiev's involvement with Mir Iskusstva coincided with the maturation of his signature style. He blended the realist grounding acquired under Repin with the decorative sensibilities and bright, saturated colors characteristic of folk art (lubok prints) and the emerging Art Nouveau aesthetic. His paintings became less about social commentary and more about celebrating an idealized vision of Russian life – robust, colorful, and full of vitality.

The World of Merchants and Festivals

Perhaps Kustodiev's most iconic and enduring subjects are the Russian merchant class and traditional folk festivals. He created a distinct world populated by prosperous, often portly merchants and their wives, depicted enjoying tea ceremonies, carriage rides, and the general abundance of provincial life. Works like The Merchant's Wife at Tea (1918) and Merchant's Wife with Purchases exemplify this theme. These figures are often portrayed with gentle humor and affection, embodying a certain archetype of traditional, pre-revolutionary Russia.

His depictions are not strictly realistic portraits but rather generalized types, symbols of a specific social milieu. The settings are equally important, often featuring brightly decorated interiors, samovars gleaming, and tables laden with food, emphasizing comfort and prosperity. The colors are bold and cheerful, contributing to an atmosphere of contentment and well-being.

Equally famous are his depictions of Russian festivals, particularly Maslenitsa (Shrovetide or Butter Week), the vibrant folk holiday preceding Lent. Paintings like Maslenitsa (1916), Winter. Maslenitsa Festivities (1919), and various winter scenes capture the exuberant atmosphere of sleigh rides (troikas), bustling fairs, snow-covered landscapes, and communal celebrations. These works are characterized by dynamic compositions, a multitude of figures, and a palette dominated by sparkling whites, blues, and reds, evoking the crisp air and joyful spirit of the Russian winter festival. Kustodiev returned to this theme repeatedly, finding in it a perfect vehicle for his love of color, movement, and folk traditions.

Portraiture and Human Insight

While best known for his genre scenes, Kustodiev was also a highly accomplished portrait painter throughout his career. His training under Repin instilled in him a keen sense for capturing psychological depth alongside physical likeness. His early family portrait Morning (1904), depicting his wife and young son, shows a tender intimacy and mastery of light reminiscent of Impressionism.

He painted portraits of many prominent figures of his time, including fellow artists, writers, and performers. His portraits of the artist Ivan Bilibin (1901), known for his illustrations of Russian fairy tales, and Mstislav Dobuzhinsky ("Matev" mentioned in snippets, likely referring to Dobuzhinsky, another key Mir Iskusstva member) capture the distinct personalities of his "spiritual comrades."

One of his most famous portraits is that of the legendary Russian opera singer Fyodor Chaliapin (1922). Painted when Kustodiev was already confined to a wheelchair, the portrait is monumental in scale and conception. It depicts the larger-than-life basso standing dramatically against a backdrop evoking a fairground stage, suggesting his connection to the common people and the world of folk entertainment that Kustodiev himself celebrated. The portrait is a powerful statement about both the sitter's commanding presence and the artist's enduring creative vision. These portraits demonstrate his ability to work within established conventions while infusing them with his characteristic vibrancy. He stands alongside contemporaries like Valentin Serov as one of the era's significant portraitists.

Engaging with Revolution and Society

The tumultuous events of early 20th-century Russia inevitably impacted Kustodiev's life and work. During the 1905 Revolution, he contributed satirical drawings to radical journals like Zhupel (Bugbear) and Adskaya Pochta (Hell's Post). These works, such as Introduction (Entry), War, Meeting, and The Leader, sharply criticized Tsarist autocracy, bureaucracy, and military incompetence, aligning him temporarily with the forces demanding social change. This period reveals a more politically engaged side of the artist, using his skills for direct social commentary.

The October Revolution of 1917 brought even more profound changes. While the idealized world of merchants and festivals seemed increasingly distant from the harsh realities of war, revolution, and civil war, Kustodiev continued to paint, sometimes adapting his themes. His most famous response to the revolution is the painting The Bolshevik (1920). This striking, symbolic work depicts a giant, determined figure in a worker's cap, carrying a massive red banner, striding purposefully over a snow-covered city filled with tiny, scurrying people and dominated by a traditional church.

The Bolshevik is open to interpretation – is it a heroic celebration of revolutionary power, a depiction of an unstoppable force overwhelming traditional Russia, or something more ambiguous? Regardless of precise meaning, it remains a powerful and iconic image of the revolutionary era, demonstrating Kustodiev's ability to engage with contemporary events through a unique visual language that blended realism with potent symbolism. In 1923, he joined the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR), an organization that aimed to depict the life and achievements of the new Soviet state in a realistic style accessible to the masses, though his own style retained its distinctive character. His interactions during this period, such as discussions with the writer Yevgeny Zamyatin about Russia and the Bolsheviks, show his continued engagement with the intellectual currents of the time.

Illustrator and Stage Designer

Kustodiev's artistic talents extended beyond easel painting. He was a prolific and gifted illustrator, creating designs for numerous books, primarily classics of Russian literature. His illustrations for Nikolai Gogol's Dead Souls and works by Nikolai Leskov (such as Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, though Mikhail Kolotkov is mentioned in the source snippets) are particularly noteworthy. His illustrative style varied, sometimes employing detailed realism, other times adopting a more decorative, folk-inspired approach, always sensitive to the text's mood and period.

He also made significant contributions as a stage designer, primarily for the Moscow Art Theatre and other venues. He designed sets and costumes for plays by Alexander Ostrovsky, including The Storm (Groza), An Ardent Heart, and others. His stage designs often translated the colorful, picturesque qualities of his paintings onto the stage, creating immersive and visually rich environments that complemented the dramatic action. This work allowed him to synthesize his love for Russian history, folk culture, and vibrant aesthetics in a theatrical context, collaborating with directors and actors to bring classic Russian plays to life.

Art Forged in Adversity

A defining aspect of Kustodiev's later life and career was his struggle with severe illness. Around 1909, he began experiencing symptoms of what was later diagnosed as tuberculosis of the spine. He underwent several complex and painful operations, including one in Berlin in 1913 and another in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) in 1916. The latter surgery, while saving his life, resulted in paralysis from the waist down. For the last decade of his life, Kustodiev was confined to a wheelchair.

This devastating physical limitation might have ended the career of a lesser artist. However, Kustodiev displayed extraordinary resilience and determination. Unable to move freely or work from direct observation outdoors, he relied increasingly on memory and imagination. He famously remarked that his room had become his entire world, but that the world he painted remained vivid and expansive in his mind.

Remarkably, many of his most vibrant, joyful, and iconic works – including The Merchant's Wife at Tea, The Bolshevik, the Maslenitsa series, and the Chaliapin portrait – were created during this period of physical confinement. The bright colors and celebratory themes seem almost defiant in the face of his personal suffering and the surrounding societal turmoil. His continued productivity from his wheelchair is a powerful testament to his passion for art and his indomitable spirit. His wife, Julia Proshinskaya, whom he married in 1903, was a constant source of support throughout his illness. They faced tragedy together as well, including the loss of an infant son.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Reception

Throughout his career, Kustodiev participated actively in the artistic life of Russia and gained recognition both at home and abroad. He exhibited regularly with the Union of Russian Artists and, after 1910, with the Mir Iskusstva group. He also showed works at exhibitions of the Moscow Society of Art Lovers (from 1900-1901). His talent was acknowledged early on, culminating in his election as an Academician of the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1909.

Internationally, his work gained notice. He received a gold medal at the International Exhibition in Munich in 1911, confirming his standing beyond Russia's borders. His works were included in various exhibitions of Russian art abroad.

However, his art was not without its critics. Some contemporaries, particularly those aligned with more avant-garde movements or stricter realist principles, found his idealized depictions of provincial life overly sentimental or lacking in critical depth. His 1916 Maslenitsa, for instance, was reportedly criticized by some as resembling a "lubok" or "illiterate splint" painting, suggesting a perceived lack of sophistication. Despite such critiques, his work resonated deeply with a broad audience who appreciated his celebration of Russian identity, his technical skill, and the sheer visual pleasure his paintings offered. Posthumously, his reputation has solidified, and he is widely regarded as a major figure in Russian art, with his works held in prestigious collections like the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg and the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Exhibitions continue to feature his work, such as a 2017 show in London.

Legacy: The Enduring Appeal of Kustodiev's Russia

Boris Kustodiev died in Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) on May 28, 1927, at the relatively young age of 49, his health finally succumbing to the long battle with illness. He left behind a rich and diverse artistic legacy that continues to captivate viewers. His unique contribution lies in his creation of a vibrant, almost utopian vision of pre-revolutionary provincial Russia. While perhaps idealized, this vision captured an essential aspect of the national spirit – its capacity for joy, celebration, and appreciation of simple pleasures, even amidst hardship.

His artistic style, a distinctive fusion of realism, folk art aesthetics, and elements of modernism (Art Nouveau), set him apart from his contemporaries. He demonstrated that realism could be colorful, decorative, and joyful, not just critical or somber. His mastery of color, his dynamic compositions, and his affectionate portrayal of Russian types remain hallmarks of his work.

Kustodiev's influence can be seen in later Soviet art that sought to depict national life, although often with a more propagandistic intent. More importantly, his work endures because it taps into a collective memory and a nostalgic longing for a certain vision of Russia – colorful, communal, and deeply rooted in tradition. Despite living through war, revolution, and personal suffering, Boris Kustodiev chose to fill his canvases with light, color, and life. His art remains a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and a vibrant celebration of the Russian soul. He remains an essential artist for understanding the cultural landscape of Russia in the tumultuous early decades of the 20th century.