Léon Bakst, a name synonymous with the explosive colour, exoticism, and revolutionary aesthetics of the early 20th century, stands as a towering figure in the annals of art history. Primarily celebrated for his groundbreaking work with Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, Bakst was far more than a theatrical designer; he was a painter, illustrator, fashion innovator, and a pivotal member of the influential Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement. His artistic vision transcended the confines of the stage, permeating fashion, interior design, and the broader visual culture of his time, leaving an indelible mark that continues to inspire. This exploration delves into the life, multifaceted career, artistic evolution, and enduring legacy of this extraordinary artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born Lev Samoylovich Rosenberg on May 10, 1866, in Grodno, then part of the Russian Empire (now Belarus), into a middle-class Jewish family, the artist later adopted the pseudonym "Bakst," derived from his mother's maiden name, Baxter. His early artistic inclinations were evident, leading him to the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg as a non-credit student, where he studied from 1883 to 1887. Even in these formative years, Bakst demonstrated a rebellious streak against rigid academicism. A notable incident involved his painting Pietà (1886), which, despite winning a silver medal, was deemed too realistic in its depiction of biblical figures by the judges, leading to his departure from the Academy. This early confrontation with conservative artistic norms perhaps foreshadowed his later embrace of innovation.

Following his time at the Academy, Bakst worked as a book illustrator and tutor. A crucial turning point came with his travels to Paris in the early 1890s. There, he studied at the Académie Julian under Jean-Léon Gérôme, a master of academic Orientalism, and also absorbed the influences of contemporary French artists. He frequented museums, sketched avidly, and encountered the burgeoning Symbolist movement and the vibrant Post-Impressionist scene. Artists like Gustave Moreau, with his richly detailed and mystical canvases, and Odilon Redon, with his dreamlike imagery, likely resonated with Bakst's developing aesthetic. He also spent time in the studio of Finnish painter Albert Edelfelt, further broadening his artistic horizons. This period was instrumental in shaping his understanding of both Western European artistic traditions and the avant-garde currents that were challenging them.

The Mir Iskusstva Circle: Forging a New Russian Art

Upon his return to Saint Petersburg, Bakst became a central figure in one of the most significant artistic movements in Russian history: Mir Iskusstva (World of Art). Co-founded in the late 1890s with luminaries such as Alexandre Benois, a lifelong friend and collaborator, and the impresario Serge Diaghilev, Mir Iskusstva sought to revitalize Russian art by embracing aestheticism, individualism, and a synthesis of Russian traditions with Western European artistic developments. Other key members included Konstantin Somov, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, Nicholas Roerich, and Evgeny Lanceray. The group published an influential eponymous magazine, for which Bakst served as an art editor and contributed numerous illustrations and designs.

Mir Iskusstva championed a wide range of artistic expressions, from painting and graphic arts to theatre design and decorative arts. They rejected the utilitarian and overtly political art of the Peredvizhniki (The Wanderers) who had dominated the Russian art scene in the latter half of the 19th century. Instead, Mir Iskusstva artists looked to the elegance of 18th-century art, the mysticism of Symbolism, and the decorative qualities of Art Nouveau. Bakst's contributions to the movement included exquisite portraits, such as his depiction of the poet Zinaida Gippius (1906) and a sensitive portrait of fellow artist Alexandre Benois. He also painted Diaghilev himself in a striking 1906 portrait, capturing the impresario's intense and visionary character. His graphic work for the Mir Iskusstva journal showcased his mastery of line and decorative composition, often incorporating sinuous Art Nouveau forms and a refined sense of elegance.

During this period, Bakst also taught art at the Zvantseva School of Drawing and Painting in Saint Petersburg from 1906 to 1910. Among his students was Marc Chagall, who, despite later disagreements with Bakst's teaching methods, acknowledged his early influence. This teaching role further solidified Bakst's position within the Russian art world.

The Ballets Russes: A Revolution on Stage

The association with Serge Diaghilev and the Mir Iskusstva group naturally led Bakst into the realm of theatrical design, where his genius would find its most spectacular expression. When Diaghilev launched his audacious Ballets Russes in Paris in 1909, Bakst was a key artistic collaborator from the outset. His designs for the Ballets Russes were not mere backdrops or costumes; they were integral components of a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), a synthesis of music, dance, and visual art that aimed to overwhelm and transport the audience.

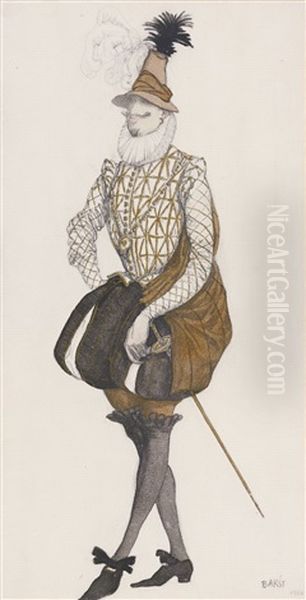

Bakst's designs for the Ballets Russes were characterized by their dazzling, often shocking, colour palettes, their exoticism, their sensuality, and their profound understanding of how fabric and form could enhance and articulate movement. He drew inspiration from a vast array of sources: ancient Greek vase painting, Cretan frescoes, Persian miniatures, Siamese court dress, Russian folk art, and the opulent styles of the Orient.

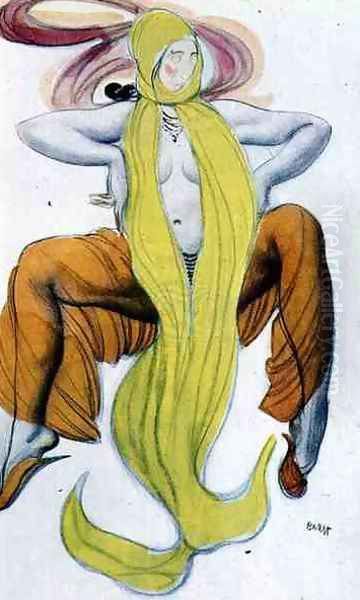

One of his earliest major successes for the Ballets Russes was Cléopâtre (1909), a dramatic ballet set to music by Anton Arensky and others, featuring dancers like Ida Rubinstein, Anna Pavlova, and Vaslav Nijinsky. Bakst's designs evoked a decadent and mysterious ancient Egypt, with bold colours and striking silhouettes that captivated Parisian audiences. This was swiftly followed by the triumph of Schéhérazade (1910), set to Rimsky-Korsakov's lush score. For Schéhérazade, Bakst created a vision of an Arabian Nights harem that was both opulent and erotically charged. His use of vibrant emerald greens, sapphire blues, deep crimsons, and shimmering golds, combined with daringly revealing costumes for dancers like Ida Rubinstein as Zobeide and Vaslav Nijinsky as the Golden Slave, caused a sensation. The sets, with their rich draperies and intricate patterns, created an atmosphere of intoxicating sensuality.

The year 1910 also saw Bakst design for Igor Stravinsky's L'Oiseau de feu (The Firebird), choreographed by Michel Fokine. While Alexandre Golovin designed the initial sets and some costumes, Bakst contributed significantly to the costumes, particularly for the Firebird herself (danced by Tamara Karsavina) and Prince Ivan. His designs captured the ballet's magical, folkloric essence with rich colours and fantastical elements, blending Russian folk motifs with an almost Byzantine splendour.

Further iconic productions followed. For Le Spectre de la Rose (1911), based on a poem by Théophile Gautier and set to music by Carl Maria von Weber, Bakst created a Biedermeier dreamscape. Nijinsky, as the spirit of the rose, wore a costume of silk petals in shades of rose and mauve, an ethereal creation that became one of the most famous ballet costumes of all time. That same year, he designed Narcisse, with music by Nikolai Tcherepnin, evoking an archaic Greek world with stylized figures and a palette that referenced ancient frescoes.

Perhaps one of his most controversial and influential designs was for L'Après-midi d'un faune (Afternoon of a Faun) in 1912, set to Claude Debussy's Prélude and choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky. Bakst's designs depicted a stylized archaic Greek landscape, with a backdrop resembling a faded tapestry. The costumes, particularly Nijinsky's faun costume with its dappled markings, were revolutionary, as was Nijinsky's angular, two-dimensional choreography. The ballet's explicit sensuality, culminating in the faun's interaction with a nymph's scarf, caused a scandal but also cemented the Ballets Russes' reputation for avant-garde daring.

Other notable Ballets Russes productions designed by Bakst include Le Dieu Bleu (1912), with its Siamese-inspired exoticism; Daphnis et Chloé (1912), set to Maurice Ravel's magnificent score, for which Bakst created idyllic pastoral scenes of ancient Greece; and La Légende de Joseph (1914), with music by Richard Strauss. His designs for Thamar (1912), based on a poem by Lermontov and set to music by Mily Balakirev, evoked a sinister and exotic Caucasian kingdom.

Even as new designers like Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov brought Cubo-Futurist influences to the Ballets Russes, Bakst continued to be a vital creative force. His later work for Diaghilev included the lavish designs for The Sleeping Princess (retitled The Sleeping Beauty for its London production) in 1921. This was Diaghilev's most ambitious and expensive production, an attempt to recreate the grandeur of the Imperial Russian ballet. Bakst's designs were a breathtaking evocation of the Baroque era, with hundreds of exquisitely detailed costumes and elaborate sets that referenced the courts of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. While the production was a critical success, its enormous cost led to financial difficulties for Diaghilev.

Artistic Style: A Fusion of Influences

Bakst's mature artistic style was a unique and potent fusion of diverse influences, masterfully synthesized into a coherent and instantly recognizable aesthetic. Orientalism was a dominant thread, but it was an Orientalism filtered through his own imaginative lens, less concerned with ethnographic accuracy than with evoking a mood of exoticism, sensuality, and mystery. He drew from Persian, Indian, Siamese, Egyptian, and ancient Greek art, often combining elements in unexpected ways.

Symbolism also played a crucial role in his artistic DNA. His designs were rarely merely decorative; they were imbued with symbolic meaning, often hinting at hidden desires, primal instincts, or mystical realms. The use of specific colours or motifs could carry psychological or emotional weight, contributing to the overall narrative and atmosphere of a production.

Art Nouveau, with its emphasis on sinuous lines, organic forms, and decorative patterning, was another key ingredient. This is evident in the flowing drapery of his costumes, the intricate details of his sets, and the overall elegance of his compositions. However, Bakst's work often possessed a dynamism and boldness of colour that went beyond the more delicate sensibilities of some Art Nouveau practitioners.

His use of colour was perhaps his most revolutionary contribution. He employed daring, often dissonant, colour combinations that could be simultaneously harmonious and startling. He understood the psychological impact of colour and used it to create specific moods, define characters, and generate visual excitement. His palettes were rich and saturated, a world away from the more muted tones prevalent in much of the theatre design of the preceding era.

Line was equally important to Bakst. His drawings reveal a masterful command of line, capable of conveying both languid sensuality and sharp, energetic movement. He often emphasized the silhouette, creating striking and memorable forms that read clearly from the stage. His figures, whether in costume designs or paintings, possess a dynamic energy, often captured in poses that suggest movement or heightened emotion.

Beyond the Stage: Painting, Illustration, and Fashion

While the Ballets Russes consumed much of his creative energy, Bakst continued to work as a painter and illustrator throughout his career. His portraiture, as seen in his depictions of Diaghilev, Benois, Jean Cocteau, and Ida Rubinstein, combined psychological insight with a strong decorative sense. He often placed his sitters in richly patterned environments or adorned them in elaborate attire, blurring the line between portraiture and costume design.

His illustrations appeared in books and magazines, showcasing his versatility. He created illustrations for works of classical antiquity, fairy tales, and contemporary literature, always bringing his distinctive flair for pattern, colour, and dramatic composition.

Bakst's influence extended profoundly into the world of fashion. The exoticism and vibrant colours of his Ballets Russes designs sparked an "Oriental craze" in Paris and beyond. Fashion designers like Paul Poiret were directly inspired by Bakst, incorporating harem pants, turbans, and rich embroideries into their collections. Poiret himself acknowledged Bakst's impact, even purchasing and exhibiting some of Bakst's sketches. Bakst also designed textiles and directly collaborated with fashion houses such as Paquin and Worth. His vision helped to liberate women's fashion from the constraints of the corset, ushering in an era of looser, more flowing silhouettes and a bolder use of colour and pattern. This influence can be seen rippling through fashion history, even inspiring later designers like Yves Saint Laurent, whose 1976 "Ballets Russes" collection paid direct homage to Bakst and his contemporaries.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

Bakst's career was deeply intertwined with a constellation of brilliant artists, writers, composers, and performers. His collaboration with Serge Diaghilev was, of course, central, a partnership that reshaped 20th-century ballet. With choreographer Michel Fokine, he created many of the Ballets Russes' early masterpieces. He also worked closely with dancers who were muses and interpreters of his vision, most notably Vaslav Nijinsky and Ida Rubinstein. Rubinstein, a wealthy heiress and performer, commissioned Bakst for several productions outside the Ballets Russes, including Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien (1911) with music by Debussy and text by Gabriele D'Annunzio, for which Bakst designed stunning costumes, and Istar.

His friendships within the Mir Iskusstva circle, particularly with Alexandre Benois and Konstantin Somov, provided a supportive and intellectually stimulating environment. While in Paris, he moved in artistic circles that included figures like Jean Cocteau, who wrote extensively about the Ballets Russes, and was aware of the work of modern masters like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. Picasso himself would later design for the Ballets Russes, bringing Cubism to the stage. Bakst's relationship with these avant-garde painters was complex; while he admired their innovation, his own style remained rooted in a more decorative and representational tradition, albeit a highly stylized one. He also knew artists like Valentin Serov, a renowned Russian portraitist, and Mikhail Vrubel, a key figure of Russian Symbolism whose intense, jewel-like paintings shared some affinities with Bakst's own aesthetic.

Personal Life and Character

Bakst's personal life had its share of complexities. He married Lyubov Pavlovna Gritsenko Tretyakova, the widow of the art collector Sergei Tretyakov. An anecdote tells of him incorporating her portrait into a stage design for a production in Saint Petersburg before their marriage, a romantic gesture typical of his theatrical flair. They had a son, André. However, the marriage was not without its difficulties, and they later separated.

Due to his Jewish heritage, Bakst faced restrictions in Russia. Despite his fame and contributions to Russian culture, he was often considered an outsider. In 1912, he was not granted permanent residency in Saint Petersburg and was effectively forced to live in exile in Paris, which became his primary base for the remainder of his life. This experience undoubtedly colored his perspective and perhaps fueled his embrace of the more cosmopolitan art world of Paris.

During World War I, despite the turmoil, Bakst continued to work, designing for various productions and even undertaking a trip to the United States in 1922. He was known for his meticulous attention to detail, his passionate dedication to his art, and a somewhat flamboyant personality that matched the exuberance of his designs.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Bakst continued to design for the stage, though perhaps not with the same consistent groundbreaking impact as his pre-war Ballets Russes period. He worked on productions in Paris, London, and New York. His designs for The Sleeping Princess in 1921 were a monumental achievement, a testament to his enduring skill and vision, even if they didn't spark the same kind of revolutionary fervor as Schéhérazade or Faune.

Léon Bakst died in Paris on December 27, 1924, from lung problems. His death marked the end of an era, but his influence was far from over. His work had irrevocably changed the landscape of theatrical design, demonstrating that sets and costumes could be powerful artistic statements in their own right. He elevated stage design to a high art, influencing generations of designers who followed.

His legacy is preserved in his stunning drawings and paintings, which are held in major museums around the world, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg. The Pushkin Museum in Moscow has also held significant retrospectives of his work. His designs continue to be studied for their artistic brilliance, their technical mastery, and their profound understanding of theatrical effect.

The vibrant colours, exotic themes, and dynamic energy of Bakst's art continue to captivate. He remains a symbol of a period of extraordinary artistic ferment, a time when boundaries between art forms were dissolving, and artists dared to dream in the most vivid hues imaginable. His vision helped to define the aesthetic of the early 20th century, and his influence on theatre, fashion, and design resonates to this day. He was, in essence, a painter of dreams, an architect of fantasy, and a true revolutionary of the stage.

Conclusion: The Unfading Brilliance of Bakst

Léon Bakst was more than an artist; he was a phenomenon. His arrival on the Parisian scene with the Ballets Russes was like a burst of exotic fireworks, forever altering the perception of what theatre could be. He demonstrated that stage design was not merely about creating a backdrop but about crafting an entire world, an immersive sensory experience that could transport, shock, and enchant. His bold synthesis of Eastern and Western aesthetics, his fearless use of colour, and his ability to translate music and narrative into breathtaking visual poetry set a new standard for theatrical art.

From the opulent harems of Schéhérazade to the archaic mysteries of L'Après-midi d'un faune, Bakst's creations were imbued with a potent blend of sensuality, exoticism, and psychological depth. His influence rippled out from the stage to transform fashion, popularizing new silhouettes and a taste for the "Oriental." As a key member of Mir Iskusstva, he played a vital role in the renaissance of Russian art and its introduction to the wider world. His collaborations with Diaghilev, Fokine, Nijinsky, Stravinsky, and many others represent some of the most fertile artistic partnerships of the 20th century. Léon Bakst's legacy is one of audacious beauty and transformative vision, a legacy that continues to inspire and dazzle over a century later.