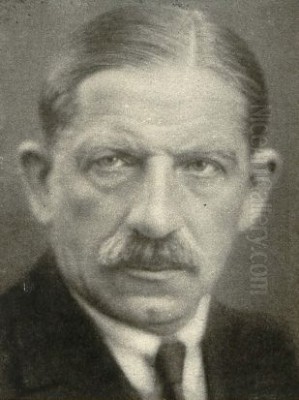

Henryk Uziembło (1879–1949) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of Polish art at the turn of the 20th century and beyond. A versatile artist, Uziembło distinguished himself not only as a painter with a remarkable sensitivity to colour but also as an innovative decorative artist, graphic designer, and influential teacher. His career spanned a dynamic period of artistic evolution in Europe, and his work reflects a fascinating synthesis of international trends and a deep engagement with Polish cultural identity. From the vibrant hues of his canvases to the intricate designs of his interiors and applied arts, Uziembło left an indelible mark on the artistic landscape of Poland, contributing significantly to the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement and the development of modern Polish design.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Myślachowice, near Trzebinia, in 1879, Henryk Uziembło's artistic journey began with a solid academic grounding. His formal training commenced at the State Industrial School (Państwowa Szkoła Przemysłowa) in Kraków, specifically in its Department of Artistic Industry (Oddział Przemysłu Artystycznego), where he studied from 1893 to 1897. This early exposure to the principles of applied arts and crafts would prove foundational to his later multifaceted career. The Kraków of this era was a burgeoning centre of artistic activity, deeply influenced by the ideals of the Young Poland movement, which sought to revive national culture through art, literature, and design.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Uziembło moved to Vienna, a vibrant imperial capital and a crucible of modernist thought. From 1897 to 1902, he enrolled at the prestigious Kunstgewerbeschule des Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie (School of Applied Arts of the Austrian Museum for Art and Industry). This institution was at the forefront of design education, closely associated with the Vienna Secession movement, which championed the integration of art into all aspects of life. Figures like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann were transforming the artistic landscape, and the atmosphere was electric with new ideas about form, function, and ornamentation. Uziembło's time in Vienna undoubtedly exposed him to these progressive concepts and honed his skills in decorative design.

His educational pursuits did not end there. Uziembło further supplemented his studies with periods in Paris and London. Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world, offered exposure to Post-Impressionism, Art Nouveau, and the nascent stirrings of Fauvism and Cubism. London provided insights into the enduring legacy of the British Arts and Crafts movement, spearheaded by figures like William Morris and John Ruskin, which emphasized craftsmanship and the social value of art. This comprehensive and international education equipped Uziembło with a diverse toolkit of styles, techniques, and philosophies.

Back in Kraków, Uziembło also benefited from the mentorship of two towering figures of Polish art: Tadeusz Axentowicz and Stanisław Wyspiański. Axentowicz, known for his elegant portraits and scenes of Hutsul folk life, was a respected professor at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts. Wyspiański, a true polymath – painter, playwright, poet, and designer – was a leading light of the Young Poland movement, celebrated for his visionary stained glass windows, murals, and theatrical designs. Their guidance would have been invaluable in shaping Uziembło's artistic vision and his commitment to a distinctly Polish modernism.

The Parisian Influence and Development of Style

The allure of Paris, a city synonymous with artistic innovation and freedom, exerted a considerable influence on Henryk Uziembło, particularly around 1910. His time spent in the French capital, whether for formal study or independent exploration, immersed him in an environment where colour was being radically re-evaluated. The legacy of Impressionism, with its focus on light and fleeting moments, had paved the way for the more subjective and expressive colour palettes of Post-Impressionists like Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh. Concurrently, the Fauvist movement, led by Henri Matisse and André Derain, was exploding onto the scene with its audacious use of non-naturalistic, vibrant hues.

This Parisian milieu profoundly impacted Uziembło's approach to painting. He developed what contemporaries and later critics described as a unique "colour sense" and a remarkable "sensitivity to colour." This suggests an intuitive and sophisticated understanding of chromatic harmonies, contrasts, and emotional resonances. His works from this period, and indeed throughout his career, are often characterized by a bold yet refined use of colour, moving beyond mere representation to evoke mood and atmosphere. This sensitivity was not confined to his easel paintings but permeated his decorative work as well, where colour played a crucial role in defining space and creating visual impact.

While it is difficult to pinpoint direct stylistic allegiances to specific Parisian schools, the general atmosphere of experimentation and the emphasis on colour as an autonomous expressive element clearly resonated with Uziembło. He absorbed these influences and integrated them into his own artistic language, which remained rooted in a strong sense of form and often drew inspiration from Polish themes and aesthetics. His painting Cyklemeny (Cyclamens), dating from around 1910, is often cited as a representative work from this period, likely showcasing this heightened colour awareness and decorative sensibility, possibly with floral motifs rendered in a style that balanced natural observation with artistic interpretation, a hallmark of Art Nouveau and related movements.

A Master of Decorative Arts and Interior Design

Henryk Uziembło was a pioneering figure in modern Polish decorative arts, a field to which he dedicated a significant portion of his creative energy. His training at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna, with its emphasis on the integration of art and craft, laid a strong foundation for his work in this domain. He became a prominent member and driving force within the Towarzystwo Polska Sztuka Stosowana (Polish Applied Art Society), an organization established in Kraków in 1901. This society, deeply influenced by the ideals of the British Arts and Crafts movement championed by William Morris, aimed to elevate the status of applied arts, promote high standards of craftsmanship, and foster a distinctively Polish national style in design.

Uziembło's contributions to decorative arts were remarkably diverse. He designed polychrome prints, intricate stained glass windows, vibrant mosaics, and elegant bookbindings. His vision extended to complete interior environments, where he orchestrated a harmonious interplay of colour, material, and form. Among his notable interior design projects were the concert hall of the Dluski Sanatorium in Kraków, the Uciecha cinema, the renowned Bagatela Theatre, and the interiors of the Kraków Hotel. These projects allowed him to implement his design philosophy on a grand scale, creating spaces that were both functional and aesthetically rich.

His interior design style was often characterized by what was termed a "looking back" aesthetic. This did not imply a slavish imitation of past styles but rather a creative reinterpretation and synthesis of historical elements within a modern framework. Uziembło skillfully wove together influences from Rococo, the Empire style, and even Oriental and Polish folk art. This eclectic approach, popular in French and Austrian decorative arts of the time, allowed for a rich visual vocabulary. He was known for his bold colour experiments within these interiors, often employing complex decorative patterns and multi-coloured inlays to create opulent and engaging environments. For instance, his designs for the Bagatela Theatre and Uciecha cinema showcased a masterful blend of classicism with folk art motifs, demonstrating a profound understanding of both historical precedent and national heritage.

Uziembło's work in decorative arts also included significant contributions to ecclesiastical spaces and public buildings. He created decorative elements for the Wawel Castle Senate Hall, a project of immense national importance. His stained glass designs, in particular, would have drawn upon the legacy of his mentor Stanisław Wyspiański, who had revolutionized the medium in Poland. Uziembło's commitment to the applied arts helped to shape a modern Polish design identity, one that valued craftsmanship, aesthetic quality, and a connection to cultural roots. He shared this commitment with contemporaries like Karol Frycz and Józef Czajkowski, who were also instrumental in the Polish Applied Art Society.

Painting: Landscapes, Still Lifes, and Sacred Art

While Henryk Uziembło made substantial contributions to the decorative arts, he remained deeply engaged with painting throughout his career. His painterly output encompassed a variety of genres, including landscapes, seascapes, still lifes, and, notably, religious themes. His approach to painting was consistently marked by the distinctive sensitivity to colour that he cultivated, particularly during his time in Paris.

His landscapes and seascapes likely captured the Polish countryside and coastal regions, interpreted through his unique chromatic lens. In an era when artists like Leon Wyczółkowski and Julian Fałat were defining Polish landscape painting with Impressionistic and Realist techniques, Uziembło would have brought his own decorative and colour-focused sensibility to the genre. His still lifes, such as the aforementioned Cyklemeny (Cyclamens) from circa 1910, provided an ideal vehicle for exploring colour harmonies and decorative arrangements. Such works often blurred the lines between fine art and decorative art, reflecting the holistic approach championed by movements like Art Nouveau and the Vienna Secession, where artists like Gustav Klimt seamlessly moved between monumental murals and easel paintings.

Uziembło also ventured into sacred art, a field with a long and rich tradition in Poland. A significant example of his work in this genre is the painting Chrystus Miłosierny (Christ the Merciful), created in 1942 for a church in Warsaw. Executed during the grim years of World War II and the German occupation of Poland, this work would have carried profound spiritual and national significance. The depiction of Christ in a field, rendered with vivid colours and distinctive brushwork, suggests a departure from purely traditional iconography, imbuing the sacred image with a personal and contemporary artistic vision. This work stands as a testament to his enduring faith and his ability to adapt his artistic style to the solemn demands of religious subject matter.

His paintings, like his decorative work, often showcased an interest in complex patterns and a harmonious balance of elements. While influenced by international trends such as Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and perhaps even hints of Symbolism or Surrealism in his thematic choices or atmospheric qualities, Uziembło's art retained a personal character. He was not a strict adherent to any single movement but rather a synthesizer, drawing on diverse sources to forge his own path. His contemporaries in Polish painting, such as Jacek Malczewski with his potent Symbolist narratives, Olga Boznańska with her psychologically insightful portraits, or Wojciech Weiss with his expressive early works, each contributed to the vibrant artistic milieu in which Uziembło operated.

Graphic Design, Illustration, and Cultural Engagement

Henryk Uziembło's artistic talents extended significantly into the realm of graphic design and illustration, areas where his flair for colour, pattern, and composition found fertile ground. He was a prolific designer of posters, a medium that had gained immense artistic prominence at the turn of the century, largely due to the pioneering work of French artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Jules Chéret, as well as Art Nouveau masters like Alphonse Mucha. Uziembło's posters would have combined striking visuals with clear messaging, contributing to the burgeoning field of graphic communication in Poland.

Book design and illustration were other important facets of his work. He created elegant bookbindings, transforming books into objects of art, a practice highly valued by the Arts and Crafts movement. His illustrations, particularly for children's books, demonstrated a keen understanding of narrative and an ability to connect with a younger audience. These works often showcased his appreciation for Polish folk motifs and natural forms, particularly plant themes, rendered with his characteristic decorative sensibility. This engagement with national style and natural elements was a common thread in the work of many Young Poland artists, who saw folk art as a vital source of authentic cultural expression.

A particularly interesting aspect of Uziembło's cultural engagement was his involvement with the Polish film industry in its nascent stages. He was a key collaborator for the film magazine Ekran (Screen). In this capacity, he likely contributed graphic design elements, illustrations, or perhaps even art criticism. His association with Ekran placed him in the company of other notable cultural figures, including the sociologist Jan Stanisław Bystroń, the influential film theorist and writer Karol Irzykowski, and the literary critic L. Skoczylas (possibly a reference to the prominent graphic artist Władysław Skoczylas, though the source is slightly ambiguous). This collaboration highlights Uziembło's broad intellectual interests and his participation in the wider cultural discourse of his time, extending beyond the traditional confines of the studio or workshop.

His work in graphic design, much like his efforts in the decorative arts, was part of a broader movement to infuse everyday objects and communications with aesthetic quality. He understood the power of visual language to shape public taste and contribute to a vibrant cultural environment. This commitment to the "total work of art" (Gesamtkunstwerk), where artistic principles permeate all aspects of life, was a defining characteristic of the era's progressive artistic movements.

Collaborations and Artistic Circles

An artist's development and impact are often shaped by their interactions with contemporaries, and Henryk Uziembło was no exception. His career was marked by active participation in artistic societies and collaborations with fellow creators. A cornerstone of his engagement was his involvement with the Towarzystwo Polska Sztuka Stosowana (Polish Applied Art Society) in Kraków. Founded in 1901, this society was a collective endeavor by artists, architects, and craftspeople dedicated to revitalizing Polish applied arts. Influenced by the ethos of the British Arts and Crafts movement and similar initiatives across Europe, such as the Wiener Werkstätte (founded by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser), the Polish Applied Art Society sought to bridge the gap between art and industry, promote high-quality craftsmanship, and cultivate a national style in design.

Within this society, Uziembło would have worked alongside other prominent figures committed to these ideals. Artists like Karol Frycz, Józef Czajkowski, and Wojciech Jastrzębowski were also key members, each contributing their unique talents to projects ranging from furniture and textile design to interior decoration and exhibition planning. Uziembło's role often involved design and decoration for significant projects undertaken or influenced by the society, such as the interiors of the Uciecha cinema or the design of libraries, reading rooms, and music rooms for sanatoria in the Galicia region. These collaborative efforts were crucial in disseminating modern design principles and fostering a sense of collective artistic purpose.

His work for the film magazine Ekran also signifies a collaborative spirit. Working alongside figures like Tadeusz Bukowski, Jan Stanisław Bystroń, and Karol Irzykowski, Uziembło contributed his visual expertise to a publication that aimed to elevate the cultural status of cinema in Poland. Such interdisciplinary collaborations were characteristic of the modernist era, where artists often crossed boundaries between different art forms and intellectual disciplines.

Furthermore, his education under Stanisław Wyspiański and Tadeusz Axentowicz placed him within a lineage of influential Polish artists. Wyspiański, in particular, was a central figure in the Young Poland movement, and his studio was a hub of creative energy. Uziembło would have been part of a generation of artists who absorbed Wyspiański's vision of a revitalized Polish art, one that was both modern and deeply rooted in national traditions. This circle would have included other students and associates of Wyspiański, such as Józef Mehoffer, another versatile artist known for his monumental stained glass and paintings. The artistic environment of Kraków at the time was vibrant, with artists like Jacek Malczewski, Leon Wyczółkowski, and Olga Boznańska actively exhibiting and shaping the course of Polish art. Uziembło's interactions within these circles, whether through formal societies, educational settings, or informal exchanges, were integral to his artistic journey.

The "Looking Back" Aesthetic and Historical Synthesis

A defining characteristic of Henryk Uziembło's approach, particularly in his interior and decorative designs, was what has been described as a "looking back" aesthetic. This concept, prevalent in certain strands of European design at the turn of the 20th century, involved a creative re-engagement with historical styles. It was not about mere historicism or slavish imitation, but rather a sophisticated process of selecting, reinterpreting, and synthesizing elements from the past to create something new and relevant to the modern era. This trend was particularly noticeable in French and Austrian interior design, where designers often drew inspiration from periods like the Rococo, Louis XVI, and Empire styles, as well as from more distant sources like Oriental art.

Uziembło masterfully adopted this approach, infusing it with a distinctly Polish sensibility by incorporating elements of national folk art. His interiors for projects like the Bagatela Theatre or the Kraków Hotel were not straightforward reproductions of historical rooms. Instead, they were imaginative compositions where classical motifs might blend with folk-inspired patterns, and traditional forms could be enlivened with bold, modern colour schemes. He demonstrated a remarkable ability to deconstruct historical styles and reassemble their components in innovative ways, creating spaces that felt both opulent and contemporary.

This "looking back" approach can be seen as a response to the rapid industrialization and perceived homogenization of culture. By drawing on historical and folk traditions, artists and designers sought to create works that possessed a sense of continuity, craftsmanship, and cultural specificity. In Poland, this often intertwined with patriotic sentiments and the desire to assert a distinct national identity, especially during a period when the nation was partitioned and lacked political sovereignty. Uziembło's work, therefore, participated in a broader cultural project of defining and celebrating Polishness through art and design.

His ability to synthesize diverse influences – from the elegance of French historical styles to the robustness of Polish folk traditions, all filtered through a modern understanding of colour and form learned in Vienna and Paris – set him apart. He was not simply an eclecticist but a skilled synthesizer who could create a cohesive and original artistic statement from varied sources. This approach resonated with the broader aims of the Young Poland movement, which also sought to forge a modern national art by drawing on history, folklore, and contemporary European artistic developments. Artists like Stanisław Witkiewicz, with his creation of the Zakopane Style in architecture and design, similarly looked to regional folk traditions as a source for a modern Polish aesthetic.

Uziembło's Enduring Place in Polish Art History

Henryk Uziembło's career unfolded during a pivotal era for Polish art, a time of intense creativity, national introspection, and engagement with international modernism. His multifaceted contributions as a painter, decorative artist, graphic designer, and educator secure him an important place within this narrative. He was a key proponent of the ideals of the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement, particularly in its efforts to elevate the applied arts and integrate artistic principles into everyday life.

His exceptional sensitivity to colour, honed through his studies and experiences in Vienna and Paris, became a hallmark of his work across all media. Whether in his vibrant paintings like Cyklemeny or Christ the Merciful, or in the rich chromatic schemes of his interior designs, Uziembło demonstrated a masterful command of colour's expressive potential. This focus on colour aligned him with broader European trends, from Post-Impressionism to Fauvism, yet he always adapted these influences to his own distinctive vision.

As a pioneer of modern Polish decorative art, Uziembło played a crucial role in shaping a national style that was both contemporary and rooted in tradition. His involvement with the Towarzystwo Polska Sztuka Stosowana and his numerous interior design projects, such as the Bagatela Theatre and the Uciecha cinema, showcased his ability to synthesize historical styles with folk elements and modern sensibilities. This "looking back" aesthetic was not merely nostalgic but a creative strategy for forging a modern identity that acknowledged its heritage. He shared this path with other Polish artists like Zofia Stryjeńska, who also drew heavily on folk traditions in her vibrant paintings and designs.

Uziembło's versatility was remarkable. He moved seamlessly between easel painting, large-scale mural and stained glass work, intimate book illustrations, and impactful poster designs. His engagement with the burgeoning film culture through his work with Ekran magazine further illustrates his forward-looking perspective and his willingness to embrace new media and cultural forms. As an educator, likely at the Institute of Fine Arts in Kraków, he would have passed on his knowledge and passion to a new generation of Polish artists.

While perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his Polish contemporaries like Stanisław Wyspiański or Jacek Malczewski, Henryk Uziembło's impact on the Polish artistic landscape was profound and lasting. He was an artist who understood the interconnectedness of all art forms and who dedicated his career to enriching the visual culture of his nation with works of beauty, craftsmanship, and enduring relevance. His legacy lies in his vibrant canvases, his thoughtfully designed interiors, and his unwavering commitment to the principle that art should permeate and elevate all aspects of human experience.