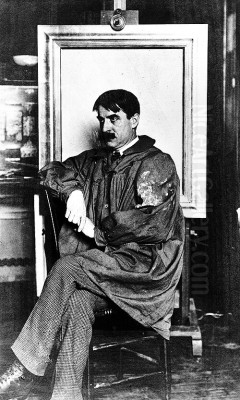

Nationality and Professional Background

Bruce Crane (1857-1937) was a prominent American landscape painter, celebrated primarily for his contributions to the Tonalist movement. Born in New York City, Crane was deeply rooted in the American artistic tradition, drawing inspiration from the landscapes of the Northeast, particularly Long Island, Connecticut, and the Adirondacks. His father, Solomon Bruce Crane, was an amateur painter himself, providing an early exposure to art that undoubtedly influenced young Bruce's path. Initially, Crane pursued a career in drafting, working for an architect and builder, which likely honed his sense of composition and structure. However, his passion for painting soon took precedence, leading him to seek formal training and dedicate his life to capturing the subtle moods and atmospheric effects of the American landscape. He became a key figure in the late 19th and early 20th-century American art scene, associated with significant art colonies and institutions.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on October 17, 1857, Bruce Crane's artistic journey began under the encouraging eye of his father. His practical experience in drafting provided a solid foundation, but the allure of fine art proved stronger. Seeking to refine his skills, Crane sought out instruction from Alexander Helwig Wyant, one of the foremost American landscape painters of the Tonalist school, around 1876 or 1877. This mentorship was pivotal. Wyant, known for his poetic and atmospheric landscapes, imparted to Crane a sensitivity to nature's nuances and the importance of capturing mood over literal representation. This period marked Crane's definitive shift towards a professional painting career, setting the stage for his development within the Tonalist aesthetic. His early works already showed a predisposition towards the intimate, contemplative scenes that would characterize his mature style.

European Sojourn and Barbizon Influence

Like many American artists of his generation seeking to broaden their horizons and refine their techniques, Bruce Crane traveled to Europe between 1878 and 1882. He spent significant time in France, immersing himself in the European artistic currents of the time. Critically, he visited and worked in Grez-sur-Loing, a village near the Forest of Fontainebleau that attracted numerous international artists. This experience brought him into close contact with the principles of the French Barbizon School. The Barbizon painters, including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, and Théodore Rousseau, emphasized direct observation of nature, plein air sketching, and a focus on capturing the atmospheric conditions and poetic sentiment of the landscape. Crane absorbed these influences, particularly the Barbizon emphasis on muted palettes, soft light, and evocative moods, which resonated deeply with the Tonalist sensibilities he had begun developing under Wyant. This European experience solidified his artistic direction, blending American landscape traditions with Barbizon aesthetics.

Establishing a Career: The Rise of Tonalism

Upon returning to the United States, Bruce Crane established his studio in New York City and quickly began building his reputation. His landscapes, characterized by their quietude, subtle color harmonies, and focus on the transitional moments of dawn, dusk, or the changing seasons, found favor with critics and collectors. He became a leading exponent of Tonalism, an artistic style that emerged in America in the 1880s, partly inspired by the Barbizon School but developing its own distinct character. Tonalism prioritized mood, atmosphere, and spirituality over detailed depiction. Artists like George Inness, Dwight William Tryon, and Crane's mentor, A. H. Wyant, were central figures. Crane's work exemplified the Tonalist ethos, often depicting hazy, melancholic scenes rendered in a limited range of closely related colors – browns, grays, golds, and soft greens – creating a unified, dreamlike effect. His success grew steadily through exhibitions at prestigious venues like the National Academy of Design.

The Old Lyme Art Colony

In the early 1900s, Bruce Crane became associated with the Old Lyme Art Colony in Connecticut, centered around the boarding house of Florence Griswold. This colony became a major center first for American Tonalism and later for American Impressionism. Crane was drawn to the picturesque landscape of the region and the collegial atmosphere among the artists. He joined fellow painters like Henry Ward Ranger, often considered the leader of the Tonalist phase at Old Lyme, and later Impressionists such as Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, and J. Alden Weir. While Crane maintained his Tonalist roots, the vibrant atmosphere and the influence of Impressionism subtly began to affect his work during this period. His time at Old Lyme was productive, providing fresh subject matter and reinforcing his position within the mainstream of American landscape painting. The interactions and shared artistic environment at Old Lyme undoubtedly played a role in the evolution of his style.

Artistic Style and Signature Themes

Bruce Crane's artistic style is primarily defined by Tonalism, though it evolved throughout his long career. His signature works often depict the quiet, unassuming beauty of the rural landscape, particularly during autumn and winter. He favored scenes bathed in the soft, diffused light of early morning or late afternoon, emphasizing atmosphere and poetic sentiment. His compositions are typically simple and direct, often featuring rolling hills, bare trees silhouetted against a luminous sky, or snow-covered fields under a muted sun. His palette was initially dominated by subtle gradations of browns, ochres, grays, and muted greens, applied with relatively smooth brushwork to enhance the sense of tranquility and unity. Works like The Year's Wane (c. 1905) exemplify this classic Tonalist phase, capturing the melancholic beauty of late autumn with remarkable sensitivity to light and mood. He sought the underlying spirit of the landscape rather than a precise topographical record.

Mature Style and Impressionist Touches

While remaining fundamentally a Tonalist, Crane's style did not remain static. Influenced perhaps by his time at Old Lyme and the growing prominence of American Impressionism, his later works, particularly after the turn of the century, often exhibit a brighter palette and looser, more visible brushwork. He began incorporating lighter blues, pinks, and lavenders, especially in his snow scenes and depictions of spring. While still focused on mood, these later paintings possess a greater vibrancy and immediacy compared to the deep, somber tones of his earlier Tonalist pieces. However, he never fully embraced the broken color and high-key palette characteristic of pure Impressionism as practiced by artists like Childe Hassam or Claude Monet. Instead, he skillfully integrated Impressionist techniques regarding light and brushwork into his established Tonalist framework, creating a unique synthesis that retained the poetic intimacy central to his vision. Works like Autumn Uplands or December Uplands showcase this mature style, balancing atmospheric depth with a more textured surface and brighter accents.

Accolades and Recognition

Throughout his career, Bruce Crane received significant recognition from the art establishment, affirming his status as a leading American landscape painter. He was a regular exhibitor at major institutions, including the National Academy of Design (where he was elected an Associate in 1897 and a full Academician in 1901), the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Art Institute of Chicago. He garnered numerous prestigious awards, including the Webb Prize from the Society of American Artists (1897), the Inness Gold Medal from the National Academy of Design (1901), silver medals at the Pan-American Exposition (1901) and the St. Louis Exposition (1904), and a gold medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco (1915). He was also an active member of influential art clubs such as the Salmagundi Club and the Lotos Club in New York, further cementing his position within the artistic community of his time. This consistent acclaim underscored the appeal and perceived quality of his evocative landscapes.

Personal Life and Character

Bruce Crane's personal life was marked by stability intertwined with some complexity. Born into a family with artistic inclinations, his path seemed somewhat predisposed towards the arts. He married Jeanne Buchard Brainerd in 1881, but the marriage ended in divorce in 1902. In a move that caused some social stir at the time, he married Jeanne's sister, Ann Brainerd, in 1904. Ann was also an artist, specializing in decorative arts and design, and they shared a daughter, also named Ann. The family resided primarily in New York City and later settled in Bronxville, New York, a suburb known for its artistic community. Crane maintained studios both in the city and, for periods, associated with his time in Old Lyme. Accounts suggest he was a dedicated and methodical artist, respected by his peers for his professionalism and the consistent quality of his work. His education was less about formal academic institutions and more focused on apprenticeship (with Wyant) and self-directed study, particularly during his European travels.

Relationships and Contemporaries

Bruce Crane operated within a rich network of artistic relationships. His most formative connection was with his teacher, Alexander Helwig Wyant, whose Tonalist approach profoundly shaped Crane's early development. He was also deeply influenced by the work of George Inness, arguably the leading figure of American Tonalism, whose spiritual and atmospheric landscapes set a high bar. Within the Old Lyme Art Colony, he interacted closely with Henry Ward Ranger, Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, and J. Alden Weir, among others. While friendly, there was undoubtedly a degree of professional competition, particularly as Impressionism gained traction alongside Tonalism. Crane's contemporaries in the broader landscape genre included fellow Tonalists like Dwight William Tryon and John Francis Murphy, whose works often shared a similar mood and subject matter. He worked during the same era as vastly different but equally significant American artists like Winslow Homer, known for his powerful marine scenes, and the visionary painter Albert Pinkham Ryder, whose mystical works occupied a unique space. Crane carved his own niche, respected for his consistent dedication to the Tonalist landscape.

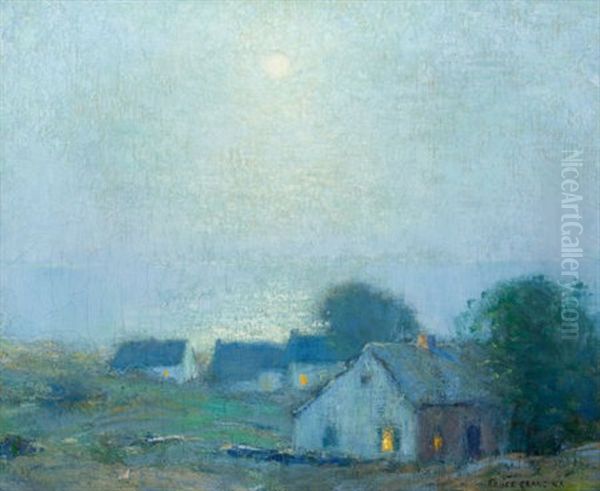

Representative Works and Artistic Style Analysis

Several paintings stand out as representative of Bruce Crane's oeuvre and Tonalist style. The Year's Wane (c. 1905, Florence Griswold Museum) is perhaps his most iconic work, perfectly encapsulating the Tonalist sensibility. It depicts a late autumn scene with bare trees under a soft, hazy sky, rendered in a harmonious palette of browns, grays, and golds, evoking a powerful sense of quiet melancholy and the cyclical nature of seasons. Autumn Uplands (various versions) showcases his mastery of depicting rolling hills bathed in the warm, diffused light of fall, often with a slightly brighter palette and more textured brushwork characteristic of his mature style. Peace at Night (c. 1898) demonstrates his ability to capture nocturnal or crepuscular scenes, emphasizing tranquility and the subtle play of moonlight or twilight. December Uplands and Frosty Morning highlight his skill in rendering winter landscapes, capturing the crisp air and the delicate effects of snow and frost with a refined sensitivity to color temperature and light. Across these works, the consistent elements are the emphasis on mood over detail, the harmonious use of a limited but expressive color range, simplified compositions, and a deep, poetic connection to the American landscape.

Artistic Achievements and Historical Evaluation

Bruce Crane's primary artistic achievement lies in his significant contribution to American Tonalism. He was one of the most successful and recognized practitioners of the style during its heyday from the 1880s through the early 20th century. His ability to consistently evoke specific moods and capture the subtle atmospheric effects of the changing seasons resonated deeply with audiences of his time, who sought solace and poetic beauty in landscape painting. His numerous awards and election to the National Academy of Design attest to the high regard in which he was held by his peers and the art establishment. Historically, Crane is evaluated as a master of the Tonalist landscape, adept at synthesizing Barbizon influences with a distinctly American sensibility. While Tonalism was later overshadowed by the rise of Modernism, Crane's work has experienced renewed appreciation in recent decades. Art historians recognize him as a key figure in the Old Lyme Art Colony and an important voice in depicting the pastoral landscapes of the Northeast. His paintings are valued for their technical skill, aesthetic refinement, and enduring poetic appeal.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Bruce Crane left a tangible legacy through his body of work, which continues to be admired and collected. His paintings are held in the permanent collections of numerous major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Gallery of Art, the Florence Griswold Museum (which holds a significant collection due to his Old Lyme connection), the Brooklyn Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others. His work remains popular in the art market, particularly among collectors of American Tonalism and Impressionism. Academically, Crane is studied within the context of late 19th and early 20th-century American art, particularly concerning the development of Tonalism, the influence of the Barbizon School, and the history of American art colonies like Old Lyme. While he may not have radically altered the course of art history in the way some avant-garde figures did, his influence can be seen in subsequent landscape painters who valued mood, atmosphere, and a poetic interpretation of nature. His enduring legacy rests on his mastery of the Tonalist aesthetic and his creation of evocative, quintessentially American landscapes that continue to resonate with viewers seeking quiet beauty and contemplation.