Wilson Henry Irvine stands as a significant figure in the story of American Impressionism, an artist whose career bridged the burgeoning art scene of late 19th-century Chicago with the influential artist colony movement in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Born in 1869 near Byron, Illinois, and passing away in 1936, Irvine dedicated his life to capturing the nuances of light and atmosphere, particularly within the American landscape. His work is characterized by a sensitive handling of color, an innovative approach to technique, and a deep connection to the natural world he depicted. As an art historian, exploring Irvine's life and work reveals a fascinating journey of artistic development and engagement with the major currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Illinois

Wilson Henry Irvine's roots lie in the American Midwest. Born on a farm near the small town of Byron, Illinois, his early life was shaped by the rural landscape. His family later moved to Rockford, Illinois, where his formal education continued. It was during his time at Rockford High School that his artistic inclinations began to truly surface. He reportedly took up drawing lessons around the age of 18, suggesting a burgeoning interest that would soon define his life's path.

Even earlier, a youthful ambition towards communication was evident; at sixteen, Irvine had already made attempts to become a newspaper reporter. This early interest in observation and reporting, though not pursued professionally in journalism, perhaps laid groundwork for the keen observational skills required for landscape painting. His formative years in Illinois provided the initial backdrop against which his artistic sensibilities began to develop, though his professional training would soon take him to the bustling city of Chicago.

Chicago Foundations: Education and Early Career

The late 1880s marked a pivotal moment for Irvine as he relocated to Chicago, a city rapidly growing in cultural and artistic importance. In 1888, seeking formal training, he enrolled in night classes at the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago (AIC). This marked the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship with the institution. For seven years, Irvine dedicated his evenings to honing his skills at the AIC, immersing himself in the academic traditions while simultaneously navigating the demands of earning a living.

During this period, Irvine did not immediately pursue fine art painting full-time. Instead, he established himself as an illustrator and graphic designer. Chicago offered ample opportunities in the commercial arts, and Irvine proved adept. He became particularly known for his skillful use of the airbrush, a relatively new technology at the time. His neighbor, Liberty Walkup, was instrumental in inventing and promoting the airbrush, and Irvine, starting around the age of twenty, became an early master of this medium, using it for commercial illustration work.

This early career in graphic arts provided financial stability and practical experience with visual communication. It also connected him with the city's burgeoning artistic community. His time at the AIC was not just about technical training; it was about building connections and engaging with fellow artists and instructors, laying the groundwork for his future transition into fine art.

Engaging with the Chicago Art Scene

While studying and working, Irvine became an active participant in Chicago's vibrant art scene. He joined several influential artist organizations, demonstrating both his commitment to his craft and his burgeoning leadership qualities. He became deeply involved with the Palette and Chisel Club, an organization founded in 1895 dedicated to fostering camaraderie and skill development among artists. Irvine served the club in significant capacities, including terms as both president and secretary.

His connections extended further. Irvine developed a close association with the prominent Chicago sculptor, Lorado Taft, a major figure associated with the Art Institute and the city's cultural life. Together, Irvine and Taft provided leadership for both the Palette and Chisel Club and the Cliff Dwellers Club, another important artistic and literary society in Chicago. Irvine was also known to attend Taft's popular Sunday painting classes, indicating a continued desire to learn and interact with established figures.

His alma mater, the Art Institute of Chicago, remained a central hub throughout his Chicago years and beyond. The AIC recognized his talent, providing him with exhibition opportunities. A notable example was a solo exhibition held during the Christmas season of 1916-1917, a significant honor that showcased his growing reputation as a fine artist. These affiliations and activities cemented Irvine's place within the Chicago art world before his eventual move east.

The Lure of Impressionism

During his time in Chicago, the currents of Impressionism, which had revolutionized French painting decades earlier, were making a significant impact in America. Exhibitions, including the groundbreaking display of French Impressionist works at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, exposed American artists and audiences to new ways of seeing and painting. Irvine, like many of his contemporaries, absorbed these influences.

His work began to shift away from the tighter rendering potentially favored in illustration towards the looser brushwork, brighter palette, and focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere characteristic of Impressionism. He embraced the practice of painting en plein air (outdoors), taking his easel directly into the landscape to capture the immediate effects of natural light. This approach became fundamental to his artistic practice for the rest of his career.

Sources suggest Irvine developed a particular method for plein air work, often using multiple canvases throughout the day. As the light changed, he would switch to a fresh canvas to accurately capture the specific atmospheric conditions of that moment. This dedication to observing and recording the subtle shifts in nature underscores his commitment to the core principles of Impressionism.

Old Lyme: Joining an American Art Colony

Around 1914, seeking new landscapes and perhaps a community more focused on Impressionist landscape painting, Irvine began spending time in Connecticut. By 1917, he had made the decisive move to Old Lyme, Connecticut, settling into what had become one of America's most famous art colonies. Centered around the boarding house of Miss Florence Griswold – now the Florence Griswold Museum – Old Lyme attracted a host of prominent American Impressionists.

The colony, sometimes referred to as an "American Barbizon" (after the French precursor) or playfully as the "land of Lyme," provided a supportive and stimulating environment. Artists lived, worked, and socialized together, sharing ideas and critiques. The picturesque Connecticut landscape, with its rolling hills, meandering rivers, and proximity to the coast, offered endless inspiration. Irvine quickly became an integral part of this community.

He joined fellow artists who were already established figures or rising stars in American Impressionism. Key figures associated with the Old Lyme colony during its peak years included Childe Hassam, perhaps the most famous American Impressionist; Willard Metcalf, known for his sensitive New England landscapes; Henry Ward Ranger, an earlier Tonalist painter who was pivotal in establishing the colony; Frank DuMond, an influential teacher; and Matilda Browne, one of the notable female artists active in the group. Irvine thrived in this atmosphere, contributing actively to the colony's artistic life.

The Lyme Art Association and Continued Engagement

Irvine's involvement in the Old Lyme community extended beyond informal interactions at the Griswold house. He became an active member of the Lyme Art Association, which was formally organized in 1914 and opened its own gallery in 1921. This association provided a crucial venue for the colonists to exhibit and sell their work locally, fostering a sense of collective identity and purpose.

Irvine regularly exhibited his paintings at the Lyme Art Association's gallery, contributing to its reputation as a showcase for American Impressionism. His participation solidified his standing within the colony and provided a consistent platform for his evolving work. The association played a vital role in sustaining the artistic community in Old Lyme, and Irvine was a dedicated participant throughout his years there. His connection to Old Lyme would remain profound for the rest of his life, and the landscapes of the region would become synonymous with his art.

Mastering Light, Texture, and Atmosphere

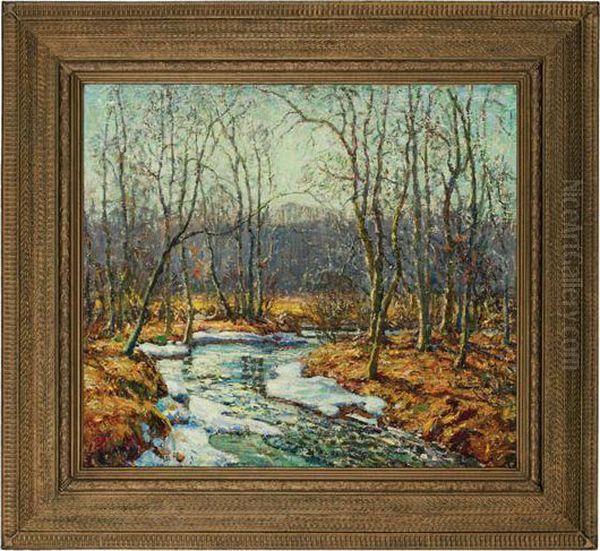

Wilson Henry Irvine's mature style is defined by his exceptional ability to render light and texture. While firmly rooted in Impressionism, his work often possesses a unique sensitivity to the tactile qualities of the natural world – the rough bark of a tree, the shimmer of light on water, the delicate structure of leaves. He achieved this through a combination of broken brushwork, a nuanced color palette, and careful observation.

His en plein air practice was crucial. By working directly from nature, he could capture the specific quality of light at different times of day and under various weather conditions. His paintings often depict the dappled sunlight filtering through trees, the cool shadows of late afternoon, or the hazy atmosphere of a summer day. He wasn't merely recording scenes; he was interpreting the mood and feeling evoked by the interplay of light, color, and form.

His brushwork, while often loose and suggestive in the Impressionist manner, could also be controlled and descriptive when rendering specific textures. This balance between capturing fleeting effects and conveying the tangible substance of the landscape gives his work a distinctive character. He moved beyond simple imitation to create paintings that resonate with sensory experience.

Innovation: Prismatic Painting

Never content to simply follow established methods, Irvine was also an innovator. Later in his career, he developed a technique he referred to as "Prismatic Painting." This involved viewing his subject through a specially prepared glass prism. The prism would break the light and slightly abstract the forms, guiding his eye and hand to apply paint in a way that emphasized vibration and luminosity.

This technique resulted in paintings with a particularly soft, shimmering quality. The edges might appear slightly blurred, and colors could blend in unexpected ways, creating an effect akin to looking through textured glass or observing a scene on a humid day. It was a unique approach to capturing the optical effects of light and atmosphere, pushing the boundaries of traditional Impressionist techniques.

While not universally adopted or perhaps even fully understood by all his contemporaries, Prismatic Painting demonstrates Irvine's experimental spirit and his lifelong fascination with the properties of light. It suggests an awareness of Post-Impressionist ideas about color theory and optical mixing, possibly influenced by artists like Georges Seurat, even as he remained committed to landscape subjects. This technique adds another layer of complexity and interest to his artistic output.

European Travels and Influences

Like many American artists of his generation, Irvine sought firsthand experience with European art. In the late 1920s, he traveled abroad, spending time primarily in Western Europe, including France and likely Great Britain and Spain. This period provided an opportunity to study the works of the French Impressionist masters directly and to experience the landscapes that had inspired them.

Seeing the works of artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley in person undoubtedly deepened his understanding of Impressionist principles. He also likely encountered Post-Impressionist developments. While his fundamental style remained rooted in American Impressionism and his preferred subject matter continued to be the American landscape, his European travels likely refined his technique and broadened his artistic perspective.

Upon returning to the United States, these experiences were integrated into his work. His later paintings sometimes show an even greater confidence in handling light and color, perhaps reflecting the lessons learned abroad. The European sojourn served not to fundamentally change his direction but to enrich the artistic vision he had already established.

Representative Works and Signature Themes

Wilson Henry Irvine's body of work primarily consists of landscapes, capturing the changing seasons and diverse scenery of New England and occasionally other regions. His paintings often feature woodlands, streams, harbors, and village scenes. He had a particular affinity for depicting trees, exploring their varied forms and textures throughout the year.

One notable later work is Willows in Landscape (1936). This painting exemplifies his mature style, showcasing his ability to capture the specific light and atmosphere of springtime. The composition contrasts the delicate, budding forms of the willow trees in the foreground with a tranquil pond or river in the background, all rendered with his characteristic sensitivity to light and color harmonies.

Another example, Summer Day at the Harbor, demonstrates his skill in depicting coastal scenes, capturing the bright sunlight reflecting off the water and boats. Throughout his oeuvre, common themes emerge: the beauty of the rural American landscape, the passage of time as marked by the seasons, and the profound effects of natural light on the perceived world. His works invite viewers to appreciate the quiet poetry of everyday nature.

Recognition, Exhibitions, and Legacy

Wilson Henry Irvine achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. He exhibited widely beyond the Art Institute of Chicago and the Lyme Art Association. His work was shown at prestigious venues such as the National Academy of Design in New York, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

A significant accolade came in 1915 when he was awarded a Silver Medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, a major international event that showcased artistic achievements from around the world. This award cemented his national reputation. He was also elected an Associate Member of the National Academy of Design.

Today, Irvine's paintings are held in the permanent collections of numerous important American museums and institutions. These include his alma mater, the Art Institute of Chicago; the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme; the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (which absorbed the Corcoran collection); the Smithsonian American Art Museum; and the Union League Club of New York, among others. His legacy lies in his contribution to American Impressionism, particularly his mastery of light and texture, his connection to the influential Old Lyme art colony, and his innovative spirit as seen in techniques like Prismatic Painting. He stands alongside contemporaries like Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, and fellow Chicago artists such as Pauline Palmer, as a key interpreter of the American landscape through an Impressionist lens.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Wilson Henry Irvine's artistic journey traces a path from the American Midwest to the heart of the American Impressionist movement in New England. Starting with a foundation in commercial art and academic training in Chicago, where he collaborated with figures like Lorado Taft, he evolved into a dedicated landscape painter deeply influenced by Impressionism. His move to Old Lyme placed him among the leading practitioners of the style in America, contributing significantly to the colony's artistic output alongside artists like Hassam and Metcalf.

His enduring fascination with light, atmosphere, and texture, combined with his innovative spirit exemplified by Prismatic Painting, resulted in a body of work that captures the beauty and subtlety of the American landscape with sensitivity and skill. While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his Old Lyme contemporaries, Wilson Henry Irvine remains an important figure whose paintings continue to resonate with viewers, offering a luminous and poetic vision of the natural world. His work provides valuable insight into the development and character of American Impressionism at the turn of the twentieth century.