Willard Leroy Metcalf stands as a significant figure in the story of American art, particularly celebrated for his evocative landscape paintings that capture the distinct beauty of the New England countryside. A founding member of the influential group known as "The Ten American Painters," Metcalf navigated the transition from traditional academic training and illustration to become one of the foremost American Impressionists. His life (1858-1925) spanned a period of immense change in the art world, and his work reflects both his rigorous training and his sensitive response to the nuances of light and atmosphere.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born on July 1, 1858, in Lowell, Massachusetts, Willard Leroy Metcalf showed artistic inclinations from a young age. His family, recognizing his talent, supported his pursuits. His formal artistic journey began not in painting, but in wood engraving, apprenticing to the landscape painter George Loring Brown in Boston starting around 1874. Brown, though known for his landscapes in an older style, provided Metcalf with foundational skills. This early exposure to landscape themes likely planted seeds for his later specialization.

Seeking more structured training, Metcalf enrolled at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which had recently opened. There, he studied under prominent instructors, including Otto Grundmann, absorbing the academic principles of drawing and composition prevalent at the time. Concurrently, he continued to develop practical skills, working as an illustrator to support himself. This dual path of formal study and commercial work was common for aspiring artists of his generation.

His skills as an illustrator gained recognition. A significant early commission came from Harper's Magazine in 1881, sending him, along with journalist Frank Cushing, to the American Southwest. His task was to illustrate articles about the Zuni people in New Mexico and Arizona. This expedition provided Metcalf with rich subject matter and valuable professional experience, honing his observational skills and ability to capture specific details of place and culture, traits that would later inform his landscape painting. His illustrations also appeared in other prominent publications like Century Magazine.

Formative Years in Europe

Like many ambitious American artists of his era, Metcalf felt the pull of Europe, particularly Paris, the undisputed center of the art world. In 1883, funded partly by earnings from his illustration work and a scholarship, he embarked on the journey abroad that would profoundly shape his artistic direction. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian in Paris, a popular choice for international students seeking rigorous academic training outside the official École des Beaux-Arts.

At the Académie Julian, Metcalf studied under respected academic painters Gustave Boulanger and Jules-Joseph Lefebvre. Their instruction emphasized strong draftsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and carefully finished surfaces – hallmarks of the French academic tradition. While Metcalf absorbed these lessons, Paris exposed him to more radical artistic currents, most notably Impressionism, which was still a revolutionary force challenging academic conventions.

Metcalf traveled extensively during his European sojourn, visiting England, Italy, and North Africa. However, it was his time spent in the French countryside, particularly in artist colonies like Grez-sur-Loing and Giverny, that proved most transformative. In these rural settings, he associated with other artists, including fellow Americans Theodore Robinson, John Henry Twachtman, and Childe Hassam, who were also exploring Impressionist ideas.

The experience of painting en plein air (outdoors) and observing the work of French Impressionists, likely including Claude Monet whom he encountered near Giverny, gradually shifted Metcalf's focus. He began experimenting with looser brushwork, a brighter palette, and a greater emphasis on capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. While his work from this period still retained elements of his academic training, the seeds of his mature Impressionist style were clearly sown. He exhibited work at the Paris Salon of 1888, a mark of professional recognition.

Return to America: New York and Teaching

Metcalf returned to the United States around 1889 and settled in New York City, eager to establish his career. Initially, he relied on a variety of artistic activities. He painted portraits, continued to take illustration commissions, and began teaching. His European training and Salon acceptance gave him credibility, and he secured teaching positions at the Cooper Union (Woman's Art School) and later at the Art Students League of New York, influential institutions shaping the next generation of artists.

His painting during the early 1890s reflected a period of transition. While landscapes remained a key interest, he also produced figurative works and murals, including a commission for the Appellate Court House in New York. His style continued to evolve, gradually shedding the darker tones and tighter handling of his earlier academic work in favor of the brighter palette and more broken brushwork associated with Impressionism, though often applied with a distinctively American sensibility.

He became active in the New York art scene, exhibiting his work regularly. He joined the Society of American Artists (SAA) in 1896, a progressive organization formed years earlier by artists who felt constrained by the conservatism of the National Academy of Design. However, even within the SAA, Metcalf and several like-minded colleagues would soon feel the need for greater artistic independence.

This period in New York was crucial for Metcalf's professional development, establishing his reputation and allowing him to engage with the leading artistic currents in America. His teaching roles also placed him in a position of influence, contributing to the dissemination of Impressionist ideas among younger artists. However, personal and artistic challenges were brewing, leading him toward another significant shift.

A Pivotal Shift: The Call of New England

The late 1890s and early 1900s marked a period of personal and professional difficulty for Metcalf. He struggled with alcoholism and faced creative uncertainty. His marriage to Marguerite Beaufort Hailé, whom he had met in Giverny, was also under strain. Seeking a change and perhaps a path to recovery, Metcalf began spending more time away from the city, reconnecting with the landscapes that had first inspired him.

A crucial turning point occurred around 1903-1904. He spent time in Old Lyme, Connecticut, drawn to the burgeoning art colony centered around Florence Griswold's boarding house. This community, which included fellow artists like Childe Hassam and Henry Ward Ranger, provided a supportive environment focused on landscape painting in an Impressionist vein. Simultaneously, Metcalf re-engaged with the landscapes of Maine, a place he had visited earlier.

This period of retreat and immersion in nature proved transformative. Metcalf largely abandoned figurative work and illustration, dedicating himself almost exclusively to landscape painting. He found solace and renewed artistic purpose in the quiet woods, rolling hills, and coastal vistas of New England. Sources suggest this was a time of deep personal reflection, where he confronted his alcoholism and recommitted himself to his art with a singular focus.

The landscapes he began producing from this point onward marked the emergence of his mature style. They resonated with critics and collectors, bringing him newfound success and recognition. This "rebirth" cemented his reputation as a premier painter of the New England scene, capturing its distinct character through the changing seasons with sensitivity and technical brilliance. His connection to specific locations, like the Cornish Art Colony in Cornish, New Hampshire (founded by sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens), further enriched his engagement with the region's artistic communities.

Metcalf's Impressionist Vision: Style and Technique

Willard Metcalf's mature style is best characterized as a uniquely American interpretation of Impressionism, blending French influences with a native sensibility and a deep reverence for the specific character of the New England landscape. While he adopted the Impressionist emphasis on light, color, and capturing fleeting moments, his approach often retained a greater sense of underlying structure and solidity compared to some of his French counterparts like Monet.

His palette became significantly brighter after his European experiences and his immersion in landscape painting. He excelled at capturing the subtle variations in light and color specific to different times of day and, most notably, different seasons. His depictions of the crisp light of autumn, the hushed blues and violets of winter snow, the tender greens of spring, and the hazy warmth of summer are hallmarks of his oeuvre.

Metcalf's brushwork is typically lively and descriptive, varying from delicate, almost feathery strokes to more robust applications of paint, depending on the texture and form he was depicting. While often broken to convey the shimmer of light, his brushstrokes generally define forms more clearly than in the work of more radical Impressionists. There is a sense of careful observation and control underlying the apparent spontaneity. Critics often noted the "truthfulness" and lack of artificiality in his work.

He possessed a remarkable ability to convey atmosphere and mood. His winter scenes, in particular, are celebrated for their poetic tranquility and masterful handling of snow's complex interaction with light. Paintings like The White Mantle exemplify his skill in using high-keyed colors and subtle tonal gradations to evoke the quiet stillness of a snow-covered landscape. He avoided overt sentimentality, instead finding poetry in the faithful depiction of nature's realities. His style was less about optical dissolution and more about capturing the essential spirit and visual character of a place.

Masterpieces of the Seasons

Metcalf's dedication to the New England landscape resulted in a body of work celebrated for its seasonal depictions. He seemed particularly drawn to the transitional moments and the distinct palettes each season offered.

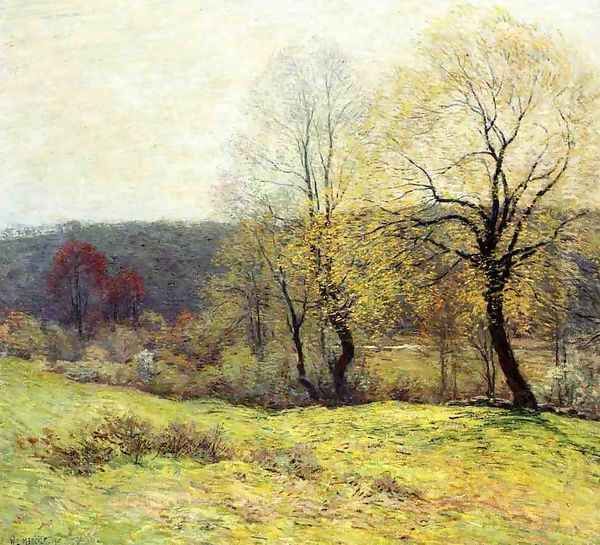

Spring in Metcalf's work often appears as a time of delicate awakening. May Pastoral (c. 1907) is a quintessential example, capturing the fresh, vibrant greens of new foliage under a soft spring sky. The painting conveys a sense of quiet energy and renewal, rendered with feathery brushstrokes that suggest the gentle movement of leaves and grasses. It avoids grandiosity, focusing instead on the intimate beauty of a rural scene.

Summer landscapes often feature lush foliage and the hazy light of warmer months. Works like Gloucester Harbor (1895), though slightly earlier, show his ability to capture the bright sunlight on water and sails, a common Impressionist theme. Later summer landscapes continued this exploration of light, often focusing on the deep greens and dappled sunlight found in wooded interiors or along riverbanks.

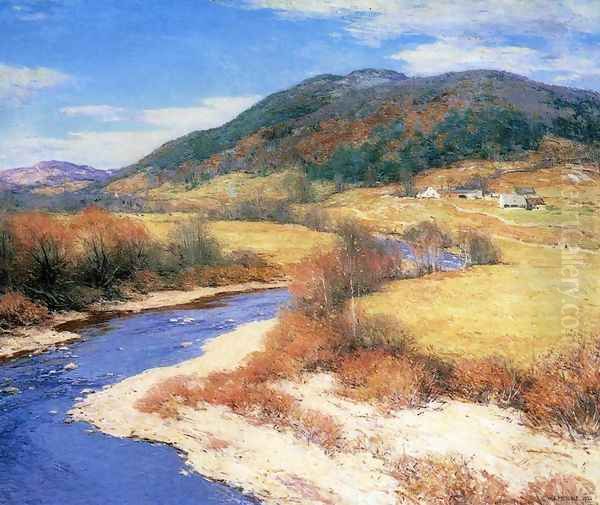

Autumn was another favored season, allowing Metcalf to explore the brilliant colors of New England's fall foliage. Indian Summer, Vermont (1922) showcases his mastery of capturing the warm, golden light and the rich reds, oranges, and yellows of the season. These works often possess a serene, almost elegiac quality, celebrating the beauty before the arrival of winter.

Winter, however, arguably inspired some of Metcalf's most iconic and critically acclaimed paintings. He seemed uniquely attuned to the subtle beauty of snow-covered landscapes. The White Mantle (1906) is a prime example, depicting a stream meandering through snow-laden banks under a soft, overcast sky. His ability to render the myriad blues, violets, pinks, and whites found in snow and shadow was exceptional. Other winter scenes, like Thawing Brook (c. 1916), capture the specific moment of transition as winter begins to yield to spring, demonstrating his keen observation of nature's cycles. These works solidified his reputation as the "poet laureate" of the New England winter.

The Ten American Painters: A Collective Voice

In late 1897, Metcalf played a pivotal role in the formation of "The Ten American Painters," often simply called "The Ten." This group represented a significant secession from the Society of American Artists (SAA). Metcalf, along with Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, John Henry Twachtman, and others, felt dissatisfied with the large, crowded, and often unevenly juried exhibitions of the SAA. They sought a smaller, more cohesive exhibiting group where their stylistically related works, largely influenced by Impressionism, could be shown to better advantage in a more harmonious setting.

The original members of The Ten were Metcalf, Hassam, Weir, Twachtman, Robert Reid, Frank W. Benson, Edmund C. Tarbell, Thomas W. Dewing, Joseph DeCamp, and Edward Simmons. (After Twachtman's death in 1902, William Merritt Chase joined the group). They represented some of the leading figures associated with American Impressionism and related aesthetic movements.

The Ten organized their own annual exhibitions, starting in 1898 and continuing for about two decades. These shows were typically held in private galleries in New York and sometimes traveled to other cities like Boston and Philadelphia. They were generally well-received by critics and the public, offering a focused look at the latest developments in American painting influenced by Impressionism.

Metcalf was an active participant throughout the group's existence. His landscapes were consistently featured, showcasing his evolving style and his dedication to New England themes. Membership in The Ten provided him with a prestigious platform and aligned him publicly with the progressive wing of American art. The group's success helped to legitimize Impressionism in America and demonstrated the viability of artists organizing independently to control the presentation of their work.

Connections and Communities: Contemporaries and Colonies

Willard Metcalf's career was interwoven with connections to numerous fellow artists and participation in important artistic communities. His time in Europe, particularly at Giverny, brought him into contact with Theodore Robinson, who was perhaps the American artist most closely aligned with Claude Monet's circle at the time. He also renewed his acquaintance with John Henry Twachtman and Childe Hassam, friendships that would prove crucial in the formation of The Ten.

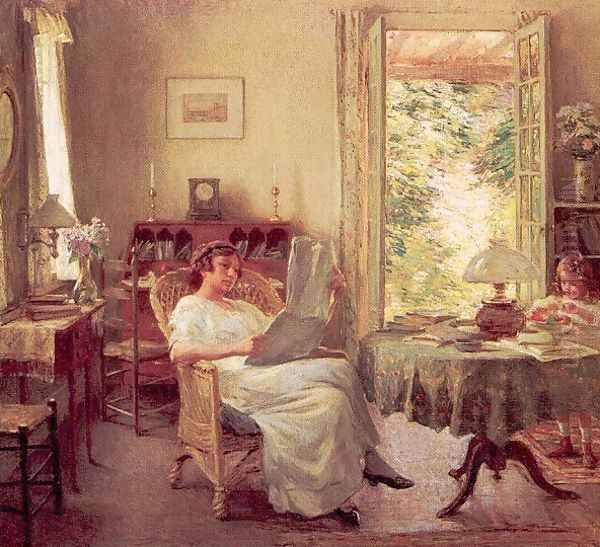

Back in the United States, his involvement with The Ten solidified his ties with Benson, Tarbell, Weir, Reid, DeCamp, Dewing, Simmons, and later Chase – all significant figures in American art at the turn of the century. These artists shared an interest in Impressionist techniques but developed distinct personal styles, ranging from Tarbell and Benson's sun-drenched figures ("Boston School") to Twachtman's highly tonal and abstract landscapes, and Dewing's ethereal Tonalist figures.

Metcalf was also deeply involved in the burgeoning art colonies that became vital centers for American Impressionism. His time at the Florence Griswold House in Old Lyme, Connecticut, placed him at the heart of what became known as the Lyme Art Colony. Here, artists gathered to paint the local landscape en plein air, sharing ideas and camaraderie. Florence Griswold herself became a legendary patron and hostess to artists like Hassam, Henry Ward Ranger, and Metcalf.

Later, Metcalf became associated with the Cornish Art Colony in Cornish, New Hampshire. Founded primarily by the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Cornish attracted a diverse group of artists, writers, and intellectuals, including painters like Thomas Dewing and George de Forest Brush, and even the playwright Augustus "Gus" Thomas, with whom Metcalf developed a close friendship (Thomas painted a portrait of Metcalf). Metcalf's presence in these colonies underscores his commitment to landscape painting and his engagement with the collective artistic life of his time. These communities provided both inspiration and a supportive network.

Recognition and Later Career

Following his artistic renewal around 1904, Willard Metcalf entered the most successful phase of his career. His focused dedication to New England landscapes, particularly his winter scenes, resonated strongly with critics and the public. His work began to sell well, providing him with financial stability.

He received numerous awards and honors, cementing his status in the American art establishment. A significant accolade was the Gold Medal awarded at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, a major international event showcasing arts and industries. His regular participation in the exhibitions of The Ten kept his work prominently before the public eye.

Museums began acquiring his paintings, recognizing their importance in the narrative of American art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., among others, added his works to their permanent collections, ensuring their visibility for future generations.

In 1924, Metcalf received one of the highest honors available to an American artist: election to the prestigious American Academy of Arts and Letters. This recognized his significant contributions to American culture. Just a year later, in 1925, shortly after his death, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., mounted a major memorial exhibition of his work, featuring 129 paintings. This exhibition traveled to other cities and served as a testament to the high regard in which he was held. His later career was marked by consistent production and sustained critical acclaim for his sensitive and authentic portrayals of the American landscape.

Personal Life and Legacy

Willard Metcalf's personal life contained complexities and challenges alongside his artistic successes. His first marriage to Marguerite Beaufort Hailé ended in divorce around 1907. He later married Henriette Alice McCrea in 1911, and they had two children. The family lived for a time in Cornish, New Hampshire, and later settled near Old Lyme, Connecticut, reinforcing his ties to these artistic centers. However, this second marriage also ended in divorce around 1920. Friends described him as having a somewhat volatile temperament, perhaps exacerbated by his earlier struggles with alcohol.

Despite these personal difficulties, his dedication to his art remained constant in his later years. Anecdotes suggest a deep, almost spiritual connection to the landscapes he painted, particularly during his period of retreat and recovery in Maine and Connecticut. This immersion in nature seems to have been both a personal solace and the wellspring of his most profound artistic achievements.

Willard Leroy Metcalf died relatively young, suffering a heart attack on March 9, 1925, in New York City, at the age of 66. His will reportedly contained a clause requesting that any works deemed potentially damaging to his reputation be destroyed, suggesting a concern for how posterity would view his artistic legacy.

Today, Metcalf is firmly established as a leading figure of American Impressionism. His legacy rests on his masterful ability to capture the specific light, atmosphere, and character of the New England landscape through the changing seasons. While influenced by French Impressionism, he forged a distinctly American style, characterized by sensitive observation, poetic feeling, and technical refinement. His work continues to be admired for its beauty, authenticity, and evocative power, securing his place among the most important American landscape painters of his generation. His journey from illustrator to academic student to celebrated Impressionist reflects the dynamic evolution of American art at the turn of the twentieth century.

Conclusion

Willard Leroy Metcalf's artistic journey charts a course from the disciplined world of nineteenth-century illustration and academic training to the light-filled canvases of American Impressionism. His deep connection to the New England landscape, forged through personal struggle and artistic rediscovery, became the defining theme of his mature work. As a founding member of The Ten American Painters and a key figure in art colonies like Old Lyme and Cornish, he actively shaped the direction of American art. Through masterpieces like May Pastoral and The White Mantle, and countless other sensitive portrayals of the seasons, Metcalf captured the unique beauty and spirit of his native region with a poetic vision and technical mastery that continue to resonate. His legacy endures in the permanent collections of major museums and in the ongoing appreciation for his authentic and evocative contribution to American landscape painting.