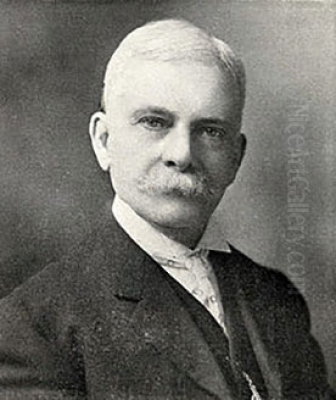

Carducius Plantagenet Ream stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. Active primarily during the latter half of the century, Ream carved a distinct niche for himself as one of Chicago's most celebrated painters, specializing in the genre of still life. Born in 1837 and passing away in 1917, his life spanned a period of immense change and development in American culture and art. He is particularly renowned for his luscious and meticulously rendered depictions of fruit, with peaches holding a special place in his oeuvre, earning him considerable acclaim both during his lifetime and posthumously. His work captured the burgeoning appreciation for realism and the tangible beauty of everyday objects in American art.

Ream's dedication to still life placed him within a rich tradition, yet he developed a personal style characterized by careful observation, sensitivity to texture and light, and an inviting sense of abundance. He was not merely a painter of objects; he imbued his subjects with a sense of presence and tactile reality that appealed strongly to the sensibilities of his time. His success was further amplified by the reproduction of his works, making his art accessible to a wider audience beyond the confines of galleries and private collections. As a foundational artist associated with the early years of the Art Institute of Chicago, his legacy is intertwined with the development of the city's artistic identity.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Carducius Plantagenet Ream was born on May 8, 1837, not in Pennsylvania as some earlier accounts suggested, but near Lancaster, Ohio. His family background connected him to the early settlement history of the region, providing a rooted American context for his future artistic endeavors. While details of his earliest artistic inclinations are sparse, it is clear that he possessed a natural talent and a drive to pursue art professionally. Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, he recognized the need for formal training, which often necessitated travel and study beyond local opportunities.

His artistic journey took him across the Atlantic, a common path for American artists seeking to refine their skills and absorb the traditions of European art. Ream is documented as having studied and exhibited in major European art centers, including London, Paris, and Munich. Exposure to the masterpieces in European museums and academies was considered essential for developing technical proficiency and understanding the historical lineage of Western art. He is known to have exhibited at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London, a significant achievement indicating a certain level of recognition early in his career. This period abroad undoubtedly shaped his technique and aesthetic sensibilities, exposing him to various styles and masters.

Upon returning to the United States, Ream did not immediately settle in Chicago. He spent time furthering his studies in New York City, then the undisputed center of the American art world. This period likely allowed him to connect with other artists, observe the latest trends, and solidify his artistic direction. New York hosted institutions like the National Academy of Design, where many artists sought to exhibit and gain recognition. It was also during this formative period that his brother, Morston Constantine Ream (1840-1898), emerged as a notable still-life painter in his own right, often working in New York. The brothers shared a specialization, suggesting a possible familial influence or shared artistic interest.

Establishing a Career in Chicago

Eventually, Carducius P. Ream chose Chicago as his primary base of operations, a decision that would prove pivotal for both his career and the city's burgeoning art scene. He arrived at a time when Chicago was rapidly growing and cultivating its cultural institutions following the devastating Great Fire of 1871. Ream became one of the city's most respected resident artists, contributing significantly to its artistic life for several decades. He established a studio and became a familiar presence in local art circles.

His association with the Art Institute of Chicago was particularly important. Ream holds the distinction of being one of the very first artists, and arguably the first Chicago-based artist, whose work was acquired for the institute's permanent collection. This early endorsement by the city's premier art institution cemented his status and provided a platform for his work to be seen by a broad public. He exhibited frequently at the Art Institute's annual exhibitions, showcasing his latest creations and maintaining his visibility.

Beyond Chicago, Ream continued to seek national recognition. He regularly submitted works to major exhibitions on the East Coast, including those held by the National Academy of Design in New York and the Brooklyn Art Association. These venues offered opportunities to compete and be seen alongside the leading artists of the day from across the country. His consistent presence in these exhibitions underscores his ambition and the positive reception his detailed still lifes generally received. He successfully navigated the art world of his time, balancing his strong regional identity in Chicago with a national artistic presence.

Artistic Style: Realism, Texture, and Light

Carducius Ream is best categorized as a Realist painter, working firmly within the American tradition of detailed representation that flourished in the latter half of the nineteenth century. While one source described him as an "Impressionist," this label is somewhat misleading regarding his primary output. Although his work demonstrates a keen sensitivity to light effects and sometimes a slightly looser handling than hyper-realism, its core aesthetic aligns more closely with the meticulous observation and faithful rendering associated with Realism, particularly in the still-life genre. His aim was less about capturing a fleeting moment in the Impressionist vein and more about conveying the enduring, tangible qualities of his subjects.

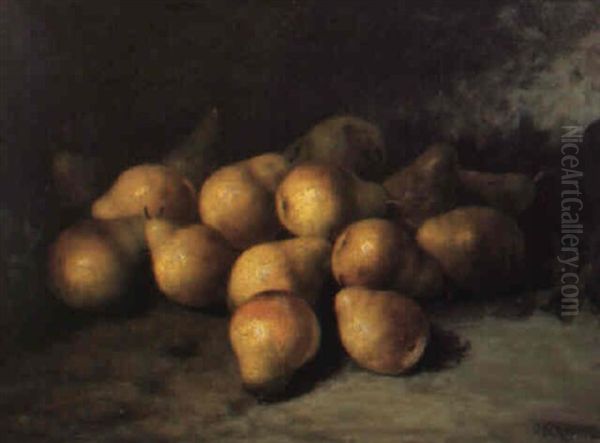

A hallmark of Ream's style is his extraordinary ability to render texture. His paintings invite the viewer to imagine the feel of the objects depicted: the soft, velvety skin of a peach, the smooth, cool surface of a grape, the crispness of a linen tablecloth, or the gleam of polished silver. This tactile quality was achieved through careful brushwork, precise drawing, and a nuanced understanding of how light interacts with different surfaces. He paid close attention to the subtle variations in color and tone that create the illusion of three-dimensionality and material substance.

The use of light is another defining characteristic of Ream's work. He often employed dramatic lighting, reminiscent of chiaroscuro techniques seen in Old Master paintings, particularly the Dutch Golden Age masters like Willem Kalf or Pieter Claesz, whose still lifes were highly admired. Light typically falls strongly on the central subjects, highlighting their forms and colors while allowing the background to recede into shadow. This creates a sense of intimacy and focus, drawing the viewer's eye directly to the carefully arranged objects. The interplay of light and shadow enhances the realism and adds a layer of quiet drama to his compositions.

His compositions are typically well-balanced and thoughtfully arranged, often featuring fruit piled invitingly in baskets, bowls, or directly on a tabletop, sometimes accompanied by glassware or silverware. While detailed, his work generally avoids the overt illusionism of the trompe l'oeil ("fool the eye") school, exemplified by contemporaries like William Michael Harnett or John F. Peto. Ream's focus seems less on trickery and more on celebrating the inherent beauty and richness of the natural forms he depicted, presenting them in an appealing, almost idealized manner.

Signature Subjects and Representative Works

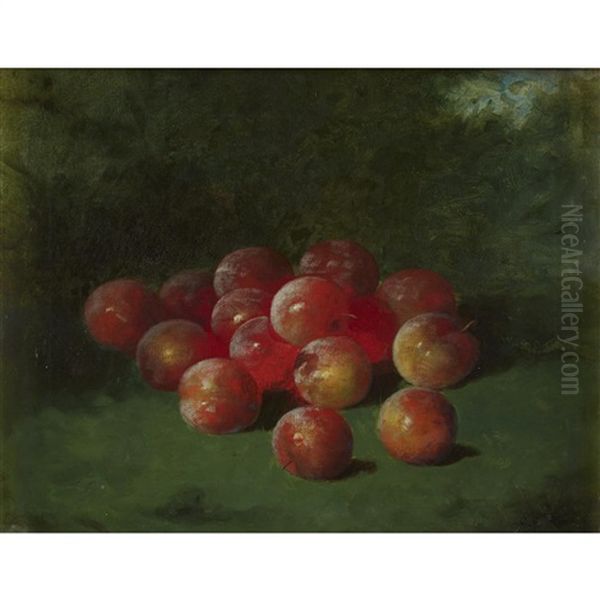

While Ream painted various still-life subjects, he became particularly famous for his depictions of fruit. Among these, peaches were arguably his favorite and most iconic subject. He captured their delicate fuzz, blushing color, and suggestion of juicy ripeness with remarkable skill. These peach paintings became highly sought after and remain some of his most recognizable works. He returned to this subject repeatedly, exploring different arrangements and lighting conditions, always emphasizing the fruit's sensual appeal.

Grapes were another frequent subject, often shown in generous bunches, their translucent skins glistening with reflected light. Works like The Grape Still Life, now housed in the Art Institute of Chicago (donated by the Peck Stacpoole Foundation), exemplify his mastery in rendering this fruit. He captured the subtle variations in color within a single bunch, from deep purples and reds to pale greens, conveying both their visual beauty and their potential sweetness. Plums, raspberries, and apples also featured prominently in his repertoire.

His painting Purple Plums, also in the Art Institute of Chicago's collection, showcases his ability to handle deeper tones and smoother textures, contrasting with the fuzziness of peaches. His raspberry paintings often depict the berries overflowing from baskets or bowls, their fragile structure and vibrant red color rendered with exquisite detail. Sometimes these fruit arrangements were presented as part of a "dessert" theme, perhaps accompanied by a wine glass or a piece of cake, under titles like Just Dessert. This theme proved exceptionally popular.

Beyond fruit, Ream occasionally incorporated other elements. Silverware, porcelain dishes, and glassware appear in some compositions, allowing him to demonstrate his skill in capturing reflective surfaces and different material properties. A work titled Violets (1895) indicates an occasional foray into floral subjects, though fruit remained his dominant theme. Regardless of the specific subject, his works consistently convey a sense of abundance, natural beauty, and quiet contemplation.

Collaboration, Context, and Contemporaries

Carducius Ream's artistic journey was intertwined with that of his brother, Morston Constantine Ream. Morston also specialized in still life, primarily working out of New York City. While direct collaborative works are not extensively documented, their shared focus suggests a mutual influence or, at the very least, a parallel development within the same genre. Carducius achieved perhaps wider recognition, particularly through his Chicago base and the popularization of his work through reproductions.

Ream worked during a vibrant period in American art history. The still-life tradition he participated in had deep roots, going back to the Peale family painters, particularly Raphaelle Peale, in the early republic. In the mid-to-late nineteenth century, still life saw a resurgence in popularity. Ream's work can be situated alongside other prominent American still-life painters of the era. Severin Roesen, a German immigrant working earlier in the century, set a high standard for elaborate fruit and flower compositions. George Henry Hall was another contemporary known for his rich depictions of fruit and flowers, often with a slightly more decorative feel.

Ream's detailed realism also connects him to the aforementioned trompe l'oeil painters William Michael Harnett and John F. Peto, although, as noted, Ream's style was generally less focused on pure illusionism. His emphasis on texture and light finds echoes in the broader American Realist movement, which included towering figures like Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer, though their primary focus lay in figurative work and landscapes, respectively.

Within the Chicago art scene, Ream was a contemporary of portrait painter G.P.A. Healy (George Peter Alexander Healy), landscape and figure painter Oliver Dennett Grover, and the influential sculptor Lorado Taft. While their subjects and styles differed, they collectively contributed to establishing Chicago as a serious center for art production and education. Ream's dedication to still life provided a crucial element to the diversity of art being created in the city.

His European studies likely exposed him to influences beyond American shores. The meticulous realism and dramatic lighting in his work certainly recall the Dutch Golden Age still-life tradition. The intimate scale and focus on humble objects might also suggest an affinity with the French master Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, whose quiet still lifes were admired for their profound simplicity and masterful technique. Although working during the rise of Impressionism, Ream largely maintained his commitment to a more traditional, detailed rendering, perhaps absorbing some lessons about light and color from Impressionists like Claude Monet or American expatriate Mary Cassatt, but translating them into his own Realist language. Artists like William Merritt Chase, who moved fluidly between Impressionism and Realism, represent another facet of the complex artistic landscape Ream navigated.

Popularity, Market, and Legacy

Carducius P. Ream achieved considerable popularity during his lifetime, a success amplified significantly by the reproduction of his paintings as lithographs. The Boston-based firm of Louis Prang & Company, famous for its high-quality chromolithographs, reproduced some of Ream's works. These prints, often marketed under appealing titles like Just Dessert, made his art accessible to a middle-class audience eager to decorate their homes. This dissemination meant that Ream's images became familiar fixtures in many American households, extending his fame far beyond the circles of elite collectors and museum-goers.

In terms of market value, Ream's works have maintained a steady presence in the American art market, particularly among collectors of traditional nineteenth-century realism and still life. While not typically commanding the astronomical prices of some of his contemporaries like Harnett, his paintings are regularly featured at auction. Estimates and sale prices generally range from the high hundreds to the low five figures, depending on the size, quality, subject matter, and condition of the piece. For example, a work like Still Life Apples might be estimated in the 0-00 range at a regional auction, while larger, more complex, or exceptionally well-preserved examples featuring his signature peaches or raspberries could achieve higher sums. The mention of a 3,000 auction price in one source seems highly anomalous and likely erroneous for C.P. Ream, possibly confused with another artist.

His legacy endures primarily through his skillful and appealing still lifes. He is remembered as a key figure in the Chicago art scene of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and as a master of fruit painting within the American Realist tradition. His work is represented in the permanent collections of major institutions, most notably the Art Institute of Chicago, which holds several examples of his work. The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, also holds his work, and examples can likely be found in other public and private collections, particularly in the Midwest.

Ream's contribution lies in his consistent dedication to the still-life genre and his ability to render everyday objects, particularly fruit, with a combination of technical precision and aesthetic appeal. He captured a sense of abundance and sensory delight that resonated with his contemporaries and continues to attract admirers today. His paintings offer a window into the tastes and values of late nineteenth-century America, celebrating the beauty found in the natural world and the pleasures of domestic life.

Conclusion: Enduring Appeal

Carducius Plantagenet Ream occupies a respected place in the annals of American art history. As a leading still-life painter based in Chicago, he contributed significantly to the cultural development of his adopted city and produced a body of work characterized by meticulous realism, sensitivity to texture and light, and an enduring appeal. His specialization in fruit subjects, particularly peaches and grapes, resulted in iconic images that captured the public imagination, further popularized through widely distributed lithographs.

While firmly rooted in the Realist tradition, his work possesses a distinct charm and warmth, avoiding sterile academicism or overt trickery. He celebrated the simple beauty of nature's bounty, arranging his subjects with care and illuminating them to emphasize their inherent qualities. His connection to the early history of the Art Institute of Chicago and his consistent exhibition record nationally underscore his professional success and standing during his lifetime. Today, his paintings remain admired for their technical skill, their inviting subject matter, and their representation of a significant current within nineteenth-century American art. Carducius P. Ream's luminous fruits continue to offer a sense of quiet delight and timeless beauty.