Edward Ladell stands as one of the most accomplished and recognisable still-life painters of the Victorian era in Britain. Born in 1821 in Hasketton, near Woodbridge, Suffolk, and passing away in 1886, Ladell dedicated his artistic career almost exclusively to the genre of still life, achieving a remarkable level of technical proficiency and developing a distinctive, highly sought-after style. His work, while rooted in historical tradition, captured the opulent tastes and domestic sensibilities of 19th-century Britain, securing him a lasting place in the annals of British art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Edward Ladell entered the world in Suffolk, a region famously associated with another giant of British art, John Constable (born 1776). While the provided information notes Ladell shared a birth year with Constable, this appears to be inaccurate regarding the year itself; Constable was born much earlier. However, the connection to Constable's native landscape might be significant, perhaps fostering an early appreciation for the natural world, even though Ladell's focus would turn indoors. His initial artistic training came under the guidance of his own father, suggesting an early immersion in creative pursuits.

Crucially, Ladell developed a deep admiration for the still-life traditions of the 17th-century Dutch and Flemish Golden Age masters. Artists like Willem Kalf, Willem Claesz. Heda, Jan Davidsz. de Heem, and Rachel Ruysch had established a visual language of extraordinary realism, intricate detail, and symbolic depth in their depictions of fruit, flowers, tableware, and other domestic objects. Ladell absorbed these lessons, particularly their meticulous rendering of textures, their dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and their carefully balanced compositions. This historical grounding provided the foundation upon which he built his own Victorian interpretation of the genre.

Artistic Style and Signature Motifs

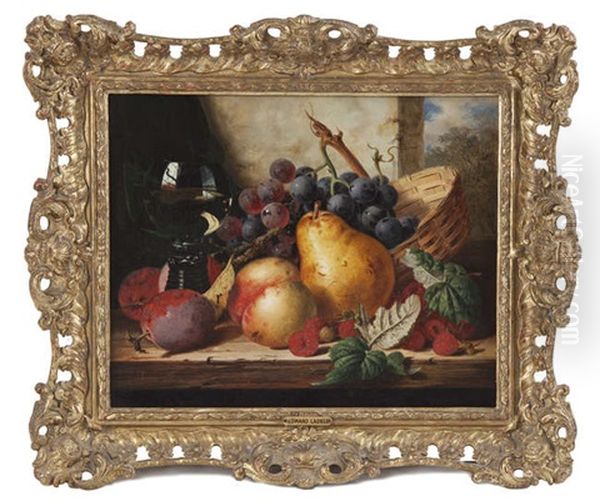

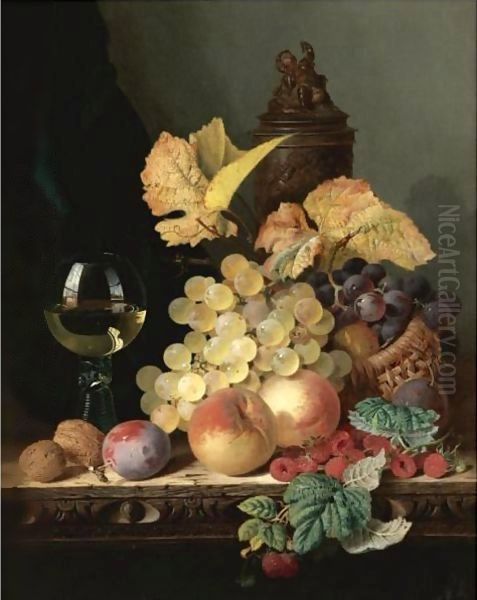

Ladell's paintings are immediately recognisable for their consistent themes, compositions, and technical execution. He specialised in relatively small-scale canvases, often measuring around 9 x 12 inches (23 x 30 cm), making them suitable for domestic interiors. His typical arrangement features a collection of objects artfully placed upon a marble ledge, sometimes partially covered by an oriental rug or velvet cloth, adding a touch of exoticism and textural richness favoured by Victorian collectors.

The objects themselves are rendered with painstaking detail. Luscious fruits – grapes, peaches, plums, raspberries – often tumble from wicker baskets or gleam invitingly. Wine glasses, frequently filled with red or white wine, capture and refract light with crystalline clarity. Other recurring elements include bird's nests, sometimes with eggs, ornate silverware, porcelain vases, nuts, and occasionally, game birds or shellfish like prawns or oysters. This combination of natural bounty and man-made luxury spoke directly to the era's appreciation for abundance and refined taste.

Ladell's mastery of light is central to his style. He often employed a strong, directional light source, illuminating the objects dramatically against a dark, undefined background. This technique, borrowed from his Dutch predecessors, not only enhances the three-dimensionality and realism of the scene but also imbues it with a quiet intensity. The interplay of light on different surfaces – the soft bloom on a peach, the hard glint on glass, the intricate weave of a basket – is captured with exceptional skill. His brushwork is typically smooth and highly finished, leaving little trace of the artist's hand and enhancing the illusion of reality.

Representative Works

Several works exemplify Ladell's characteristic style and subject matter. Still Life with Fruit, Basket and Glass (24 x 30 cm) likely showcases a typical arrangement of fruit spilling from a container alongside a reflective wine glass, demonstrating his skill in rendering varied textures and forms within a compact composition. Similarly, Still Life with fruit and glass of wine on a table (36 x 30.5 cm) presents a familiar theme, perhaps offering a slightly larger format but retaining the focus on meticulously depicted fruit and glassware.

Another titled work, Still Life with Grapes and a Glass of Wine, is noted for embodying Victorian elegance. This suggests a composition rich in detail, perhaps featuring particularly fine glassware or accompanying objects that speak to the era's aesthetic preferences. The depiction of grapes was a frequent motif for Ladell, allowing him to explore translucency and clustered forms.

A more descriptively titled piece, Still Life with a Jug, Glass, Lemon and Nuts on a Ledge, highlights the inclusion of other common elements like ceramics (the jug) and the sharp, acidic presence of a lemon, often shown partially peeled in the Dutch tradition to display technical virtuosity in rendering the pith and peel. The inclusion of nuts adds another layer of texture. These works, consistently featuring similar elements arranged with subtle variations, underscore Ladell's focused dedication to his chosen subject matter.

Career, Exhibitions, and Context

Edward Ladell established himself as a professional artist and gained recognition through participation in major London exhibitions. By 1859, his presence in annual exhibitions solidified his standing. He exhibited his works at prestigious venues including the Royal Academy (RA), the British Institution (BI), and the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) on Suffolk Street. These platforms were crucial for artists to gain visibility, attract patrons, and build their reputations in the competitive Victorian art world.

While the available information suggests Ladell was highly focused on his specific niche, it doesn't indicate direct collaborations with other contemporary painters or membership in specific artistic groups or societies beyond exhibiting bodies. His career unfolded during a vibrant period in British art. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, was challenging academic conventions with their detailed realism and literary themes. Landscape painting continued to flourish, building on the legacies of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable. Narrative and historical scenes were immensely popular, produced by artists such as William Powell Frith, while others like Frederic Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema explored classical and aesthetic themes.

Ladell operated somewhat apart from these dominant trends, dedicating himself to the quieter, more intimate genre of still life. He shared this focus with other specialists, such as George Lance, who was another prominent British still-life painter of the period. Ladell's commitment to the Dutch-inspired tradition, however, gave his work a distinct character that appealed strongly to collectors seeking finely crafted, decorative paintings for their homes. His style offered a sense of timelessness and technical assurance that contrasted with the sometimes more experimental or narrative-driven work of his contemporaries like Albert Moore or the earlier, pioneering female still-life artist Mary Moser (a Royal Academician from a much earlier generation).

Personal Life

Details about Edward Ladell's personal life reveal a partnership deeply intertwined with his art. He married Ellen Maria Levett, who initially worked as a seamstress. She became his student, learning the art of painting directly from him, and eventually, they married. Ellen Ladell also became a recognised painter in her own right, specialising, like her husband, in still life and often working in a very similar style. This similarity occasionally leads to confusion in attributions, but Ellen developed her own successful career exhibiting alongside Edward.

The couple settled in Exeter, Devon, in the southwest of England. There, they established a studio, working and likely teaching together. This move away from the primary art centre of London suggests a desire for a different pace of life or perhaps reflected established patronage in the region. Later in life, Edward Ladell became a widower. The records consulted indicate they did not leave other children, suggesting a focused life dedicated largely to their artistic partnership.

Legacy and Market Appeal

Edward Ladell's legacy rests on his position as one of the foremost Victorian practitioners of still-life painting in the Dutch tradition. His work is admired for its technical brilliance, meticulous detail, and consistent quality. He found a successful formula – the ledge arrangement, the recurring motifs of fruit, wine glasses, and objets d'art, the dramatic lighting – and perfected it throughout his career. While perhaps not an innovator in the sense of challenging artistic boundaries, he was a master craftsman within his chosen genre.

His paintings enjoyed considerable popularity during his lifetime and have remained highly sought after by collectors ever since. His works appear frequently at auction houses, consistently commanding respectable prices, which attests to their enduring appeal and recognised quality within the market for 19th-century British art. The relatively small scale and decorative nature of his paintings make them well-suited to private collections.

In conclusion, Edward Ladell carved a distinct niche for himself within the bustling Victorian art scene. By looking back to the Dutch Golden Age masters while catering to contemporary tastes, he created a body of work characterised by exquisite realism, rich textures, and a quiet, contemplative beauty. His dedication to the still-life genre resulted in paintings that are both technically accomplished and aesthetically pleasing, securing his reputation as a significant figure in the history of British still-life painting. His art continues to charm viewers with its intricate detail and celebration of material pleasures, rendered with a masterful hand.