The Dutch Golden Age, spanning roughly the 17th century, was a period of extraordinary artistic efflorescence, particularly in the realm of painting. While grand historical narratives, evocative landscapes, and penetrating portraits captured the public imagination, the genre of still life painting reached unprecedented heights of technical skill and thematic complexity. Within this vibrant milieu, Adriaen Coorte (c. 1665 – after 1707) carved a unique niche. A painter of exquisite, small-scale still lifes, Coorte’s work stands apart for its intense focus, minimalist compositions, and profound sense of quietude, offering a meditative counterpoint to the more opulent displays of his contemporaries.

The Enigmatic Life of a Middelburg Painter

Much of Adriaen Coorte's life remains shrouded in a degree of mystery, a common fate for many artists of the period whose fame did not reach the towering heights of figures like Rembrandt van Rijn or Johannes Vermeer during their lifetimes. What is known is that he was active primarily in Middelburg, the capital of the province of Zeeland, between approximately 1683 and 1707. The exact dates of his birth and death are not definitively recorded, though scholarly consensus places his birth around 1665.

Unlike many of his peers who sought fame and fortune in larger artistic centers like Amsterdam or Haarlem, Coorte seems to have remained rooted in Middelburg. Archival evidence suggests he was not initially a member of the local Guild of Saint Luke, the professional organization for painters and other craftsmen. In 1695 or 1696, he was fined by the Middelburg guild for selling paintings without being a member, an incident that perhaps points to an independent streak or a status as a "gentleman painter" who did not rely solely on his art for income. It is believed he may have eventually joined the guild, but details are scarce.

The relative obscurity of his biography contrasts sharply with the luminous clarity of his art. His surviving oeuvre, though not vast, consists of meticulously rendered compositions that invite close contemplation.

Artistic Formation and Influences

The specific details of Coorte's artistic training are not fully documented, but it is widely believed that he may have studied in Amsterdam around 1680 under Melchior d'Hondecoeter (1636–1695). Hondecoeter was a renowned painter of birds, often depicted in grand, park-like settings or as part of hunting scenes. While Coorte’s subject matter diverged significantly, focusing on humble fruits, vegetables, and shells rather than exotic fowl, Hondecoeter’s meticulous attention to texture and naturalistic detail could have been an influential starting point. Some scholars note a shared tendency to repeat certain motifs or poses, a practice common in studios where pupils learned by copying.

Beyond any direct tutelage, Coorte’s work also resonates with the earlier traditions of still life painting that had flourished in Middelburg itself. In the early 17th century, Middelburg was a significant center for still life, with artists like Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573–1621) and Balthasar van der Ast (1593/94–1657) pioneering detailed and brightly lit flower paintings and fruit pieces. While Coorte’s style is more subdued and his compositions far simpler, the legacy of careful observation and delight in natural forms prevalent in the Middelburg school may have provided a conducive artistic environment.

However, Coorte’s approach was distinctly his own. He eschewed the elaborate, crowded compositions favored by many of his contemporaries, such as the lavish "pronkstilleven" (ostentatious still lifes) of Willem Kalf (1619–1693) or Abraham van Beyeren (1620/21–1690), which often featured silverware, imported delicacies, and rich textiles designed to showcase wealth and abundance. Coorte’s vision was more introspective and focused.

The Quintessential Style of Adriaen Coorte

Adriaen Coorte’s artistic signature is characterized by several key elements that combine to create a unique and compelling body of work. His paintings are typically small, often executed on paper mounted on panel or canvas, lending them an intimate, jewel-like quality.

Simplicity and Focus

The most striking aspect of Coorte’s compositions is their radical simplicity. He often depicted a very limited number of objects – a few strawberries, a sprig of gooseberries, a bundle of asparagus, or a collection of shells – isolated against a dark, undefined background. This minimalist approach forces the viewer’s attention entirely onto the subject, allowing for an intense appreciation of its form, color, and texture. This contrasts with the more complex arrangements of artists like Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606–1684), whose works teem with a variety of objects.

The Stone Ledge or Niche

A recurring motif in Coorte’s paintings is the placement of his subjects on a simple stone ledge or within a shallow niche. This device, often with a chipped or cracked edge, serves as a rudimentary stage, grounding the objects in a shallow, defined space. The starkness of the stone provides a textural contrast to the delicate softness of fruit or the smooth gleam of shells. This compositional strategy enhances the sense of isolation and highlights the three-dimensionality of the objects. The use of a simple ledge was not unique to Coorte, but his consistent and almost exclusive reliance on it became a hallmark.

Mastery of Light and Shadow

Coorte was a subtle master of chiaroscuro. His objects are typically illuminated by a soft, directional light, often from the left, which models their forms and casts delicate shadows. This careful manipulation of light against the dark background creates a sense of drama and presence, making the humble subjects seem almost monumental despite their small scale. The play of light across a velvety peach or the translucent skin of a grape is rendered with exquisite sensitivity. This focused illumination recalls, in a much more restrained manner, the dramatic lighting seen in the works of Caravaggio and his followers, though Coorte’s intent was less about overt drama and more about quiet revelation.

Texture and Tactility

A hallmark of Coorte's technique is his extraordinary ability to render texture. The downy fuzz on a peach, the glistening dew on a strawberry, the rough fibers of asparagus, the brittle sheen of a seashell – all are conveyed with remarkable verisimilitude. His brushwork is precise and controlled, yet it never feels labored. The viewer is invited to imagine the tactile sensation of these objects, enhancing their physical presence. This attention to surface detail was a characteristic of many Dutch still life painters, including female artists like Clara Peeters (1594–c. 1657) who excelled in depicting reflective surfaces and varied textures.

Limited Palette, Rich Effect

Coorte generally employed a restrained palette, dominated by earthy tones, deep greens, rich reds, and subtle ochres, set against his characteristic dark backgrounds. This limitation, however, did not result in dullness. Instead, it allowed the inherent colors of his subjects to shine with greater intensity. The vibrant red of a strawberry or the cool green of asparagus gains an added potency from the surrounding darkness and the simplicity of the composition.

Signature Subjects and Representative Works

Coorte returned to certain subjects repeatedly, exploring their forms and textures with an almost obsessive focus. His most famous works often feature humble, everyday items, elevated to objects of profound beauty through his artistic vision.

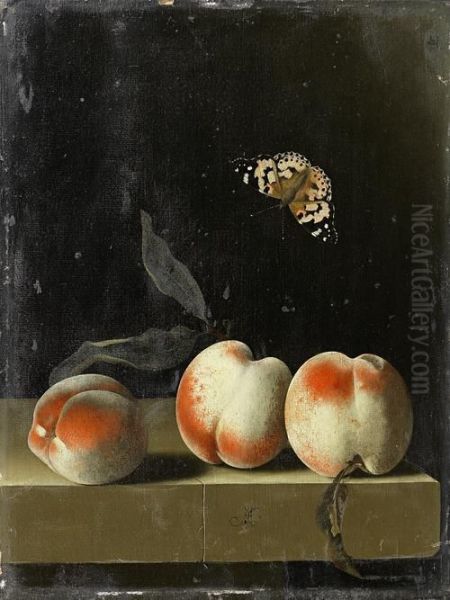

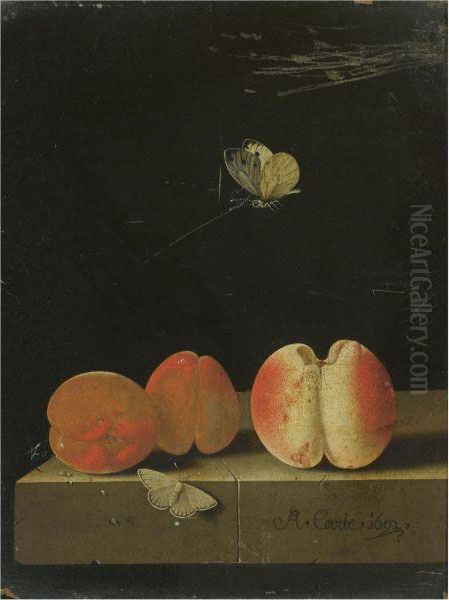

Three Peaches on a Stone Ledge (c. 1693-1695, Mauritshuis, The Hague)

This painting is a quintessential example of Coorte’s style. Three peaches, their skins rendered with a soft, velvety texture, rest on a simple stone ledge. One peach has a leaf still attached, adding a touch of naturalism. The subtle variations in color, from pale yellow to rosy blush, are captured with precision. The dark background throws the fruit into sharp relief, and the gentle light models their round forms. The simplicity of the arrangement belies the sophisticated observation and technical skill involved.

Still Life with Asparagus, Red Currants, and Strawberries (1696, Dordrechts Museum)

Here, Coorte combines a bundle of white asparagus, a sprig of vibrant red currants, and a few ripe strawberries. The asparagus, tied with a simple string, dominates the composition, its pale stalks contrasting with the intense red of the berries. The textures are beautifully differentiated: the fibrous asparagus, the translucent currants, and the dimpled surface of the strawberries. Each element is given space to breathe, contributing to a harmonious whole. A similar composition, Still Life with Asparagus and Red Currants (1703), is housed in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., showcasing his continued exploration of this theme.

A Bowl of Strawberries on a Stone Plinth (1705, Private Collection)

Coorte painted strawberries numerous times, both individually and in simple earthenware bowls. This particular work, dated 1705, shows a humble bowl filled with glistening red strawberries, some with their green calyxes still attached. The light catches the seeds and the moist surfaces of the fruit, making them appear incredibly fresh and inviting. The stone plinth, as always, provides a stark, stable base. The repetition of this subject suggests a deep fascination with its form and color.

Still Life with Shells (1696, Private Collection, on loan to the Rijksmuseum)

Besides fruits and vegetables, Coorte was also drawn to the beauty of seashells. In an era of global trade and burgeoning scientific curiosity, exotic shells were prized collector's items. Coorte depicted them with the same meticulous care he lavished on his other subjects. In this work, a variety of shells are arranged on a stone ledge, their intricate patterns, varied shapes, and pearlescent surfaces captured with remarkable fidelity. The composition highlights their sculptural qualities and the subtle play of light across their polished exteriors. These shell paintings connect Coorte to a broader Dutch interest in naturalia and exotica.

Wild Strawberries in a Wan Li Bowl (1704, Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

This work is notable for the inclusion of a Chinese Wan Li porcelain bowl, a luxury item imported by the Dutch East India Company. The delicate blue-and-white porcelain provides a refined contrast to the rustic charm of the wild strawberries. It demonstrates that while Coorte often focused on the humble, he was not averse to incorporating elements of contemporary taste and trade. The juxtaposition of the exotic porcelain with the locally gathered fruit creates an interesting dialogue between the global and the local.

The Philosophical Undertones: More Than Meets the Eye?

While Coorte’s paintings are, on the surface, straightforward depictions of natural objects, art historians have often pondered their deeper meanings. In the context of Dutch 17th-century still life, symbolism was frequently embedded in such works. Themes of vanitas (the transience of life and the futility of earthly pleasures), the bounty of nature, or even religious allegory were common.

Coorte’s work, with its emphasis on perishable items like fruit, naturally evokes the passage of time and the ephemeral nature of beauty. The chipped stone ledges might also symbolize decay and the impermanence of man-made structures. However, his paintings lack the overt symbolic apparatus of many vanitas pieces – the skulls, hourglasses, or snuffed candles found in the works of artists like Pieter Claesz. (c. 1597–1660) or Willem Claesz. Heda (1594–c. 1680).

Instead, Coorte’s symbolism, if present, is more subtle and open to interpretation. His intense focus on individual objects can be seen as a celebration of the beauty found in the everyday, a kind of secular reverence for the natural world. The quiet, meditative quality of his paintings invites contemplation, perhaps encouraging a mindful appreciation of simple things. The isolation of the objects could also suggest a sense of preciousness or vulnerability.

Some scholars have suggested that the choice of specific items, like asparagus (considered a delicacy and an aphrodisiac, and sometimes associated with the Virgin Mary in religious art), might carry particular connotations. However, without more explicit iconographic clues or contemporary textual evidence, such interpretations remain speculative. What is undeniable is the profound sense of presence and stillness that Coorte achieves, transforming humble subjects into objects of intense visual and perhaps spiritual focus.

Coorte's Place Among Contemporaries

Adriaen Coorte operated somewhat outside the mainstream of Dutch still life painting in his time. His minimalist aesthetic was a departure from the prevailing taste for abundance and complexity. While artists like Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750) or Jan van Huysum (1682–1749) were creating elaborate and highly prized flower paintings, filled with a dazzling array of blooms, Coorte’s vision was far more restrained.

His approach might be seen as having more in common with the earlier, more sober "monochrome banketjes" (monochromatic banquet pieces) of the Haarlem school, such as those by Pieter Claesz. and Willem Claesz. Heda, which emphasized tonal harmony and a limited range of objects. However, Coorte pushed this reductionist tendency even further, often focusing on just one or two types of items.

His work can also be seen as a highly individualized expression within the broader Zeeland artistic environment. While Middelburg had a strong tradition of still life, Coorte’s intimate scale and intense focus set him apart. He was not a painter of grand pronouncements but of quiet observations. This individuality may have contributed to his relative obscurity during his lifetime and for centuries thereafter. He was not an artist who loudly proclaimed his skill through complex arrangements, but one who whispered his mastery through the perfect rendering of a single strawberry.

It is also interesting to consider his work in relation to painters of different genres. The intense scrutiny he brings to his subjects, and the way light reveals form, shares a certain sensibility with the intimate genre scenes of Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), though their subject matter and scale are vastly different. Both artists, in their own ways, found profundity in the closely observed details of the world around them.

Rediscovery and Legacy

For nearly two centuries after his death, Adriaen Coorte was largely forgotten by the art world. His small, unassuming paintings did not fit the prevailing tastes of the 18th and 19th centuries, which often favored grander and more narrative subjects. It was not until the mid-20th century that his work began to be rediscovered and appreciated.

The Dutch art historian Laurens J. Bol played a pivotal role in resurrecting Coorte’s reputation. Through meticulous research and publications, starting in the 1950s (notably his 1952 article and 1977 monograph), Bol brought Coorte’s unique talent to the attention of scholars, collectors, and museums. This rediscovery coincided with a growing appreciation for more minimalist and abstract qualities in art, allowing Coorte’s work to be seen in a new light.

Since then, Coorte’s paintings have become highly sought after by collectors and museums worldwide. His works now hang in prestigious institutions such as the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Exhibitions dedicated to his work, such as the one held at the Mauritshuis in 2008, have further solidified his status as a significant, if highly individualistic, master of the Dutch Golden Age.

The prices for his paintings at auction have also risen dramatically, reflecting his enhanced art historical standing. For instance, his Still Life with Fraise-de-Bois (wild strawberries) and asparagus was offered with a high estimate in the millions of dollars. Another work, Gooseberries on a Table, also commanded significant attention when it appeared on the market.

Coorte’s legacy lies in his ability to imbue the simplest of subjects with a sense of wonder and profound beauty. His paintings are odes to the quiet dignity of everyday objects, rendered with a technical brilliance and an almost spiritual intensity. In an age often characterized by opulence and display, Coorte’s art offers a refreshing vision of intimacy, focus, and serene contemplation. He reminds us that monumentality is not always a matter of scale, but of vision. His small, quiet paintings continue to resonate with contemporary audiences, offering a timeless meditation on the beauty that can be found in the humblest corners of the world. His work has even been seen as a precursor, in spirit if not in direct influence, to later artists like Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964), who similarly dedicated his career to the intensive, meditative study of simple, everyday objects.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of a Singular Vision

Adriaen Coorte stands as a testament to the rich diversity of talent within the Dutch Golden Age. While he may not have achieved widespread fame during his lifetime, his rediscovery has revealed an artist of exceptional skill and a unique sensibility. His minimalist compositions, his mastery of light and texture, and his intense focus on humble subjects create a body of work that is both visually captivating and deeply meditative.

In a world that is often loud and overwhelming, Coorte’s quiet paintings offer a space for contemplation and a renewed appreciation for the simple beauties of the natural world. He was a painter who found profundity in the particular, transforming a handful of asparagus or a few strawberries into objects of enduring artistic significance. His legacy is a reminder that true artistry can be found in the most unassuming of places, and that a singular vision, pursued with dedication and skill, can transcend time and speak powerfully to future generations. Adriaen Coorte, the enigmatic master of Middelburg, remains a cherished and distinctive voice from one of art history's most luminous periods.