Carl Georg Adolph Hasenpflug stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of 19th-century German art. Born at a time when Romanticism was beginning to reshape the artistic and intellectual contours of Europe, Hasenpflug carved a distinct niche for himself as a painter of architectural subjects, particularly the majestic and often decaying churches and ruins of medieval Germany. His work is characterized by a meticulous attention to detail, a profound sensitivity to atmosphere, and a deep engagement with the Romantic era's fascination with history, nature, and the sublime.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Berlin

Carl Georg Adolph Hasenpflug was born on September 23, 1802, in Berlin, then the capital of Prussia. His early life was not immediately directed towards the arts. He initially apprenticed in his father's shoemaking workshop, a practical trade that seemed far removed from the world of canvases and pigments. However, the young Hasenpflug harbored artistic inclinations that would soon lead him down a different path.

His formal artistic journey began when he started studying under Carl Wilhelm Gropius (1793-1870), a prominent decorative painter, diorama artist, and theatre designer in Berlin. Gropius, who also owned a significant art dealership and publishing house, was a well-connected figure in the Berlin art scene. This apprenticeship provided Hasenpflug with foundational skills in drawing, perspective, and the handling of paint, likely with an emphasis on precision required for decorative and stage work. It was through Gropius that Hasenpflug's talent began to gain recognition.

A pivotal moment in his early career was his encounter with the influential architect and painter Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841). Schinkel was a towering figure in Prussian Neoclassicism and also produced Romantic landscape paintings. His emphasis on architectural accuracy, combined with an ability to evoke mood, undoubtedly left a mark on Hasenpflug. The artistic environment in Berlin was vibrant, with the Berlin Academy of Arts (Preußische Akademie der Künste) serving as a central institution. Hasenpflug's talent did not go unnoticed, and he reportedly received support, possibly a stipend, from King Frederick William III of Prussia, which enabled him to pursue further studies at the Berlin Academy of Arts around 1820. This royal patronage was crucial for many aspiring artists of the era, providing them with the means to dedicate themselves to their craft.

The Embrace of Romanticism and Architectural Themes

The early 19th century in Germany was dominated by the Romantic movement, a complex cultural phenomenon that reacted against the Enlightenment's rationalism and Neoclassicism's formal order. German Romanticism, in particular, emphasized emotion, individualism, the glorification of the past (especially the Middle Ages), and a deep connection with nature. Artists like Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), perhaps the most iconic German Romantic painter, explored themes of spirituality, solitude, and the sublime through evocative landscapes. Other contemporaries like Carl Blechen (1798-1840) also infused their landscapes and architectural views with a Romantic sensibility, often depicting ruins or dramatic natural settings.

Hasenpflug was deeply imbued with this Romantic spirit. He found his primary inspiration not in the idealized classical world, but in the Gothic architecture of Germany's medieval past. Churches, cathedrals, monasteries, and their ruins became his signature subjects. These structures were seen by Romantics as embodying a national spirit, a connection to a more spiritual and heroic age, and a poignant reminder of the passage of time and the transience of human endeavors.

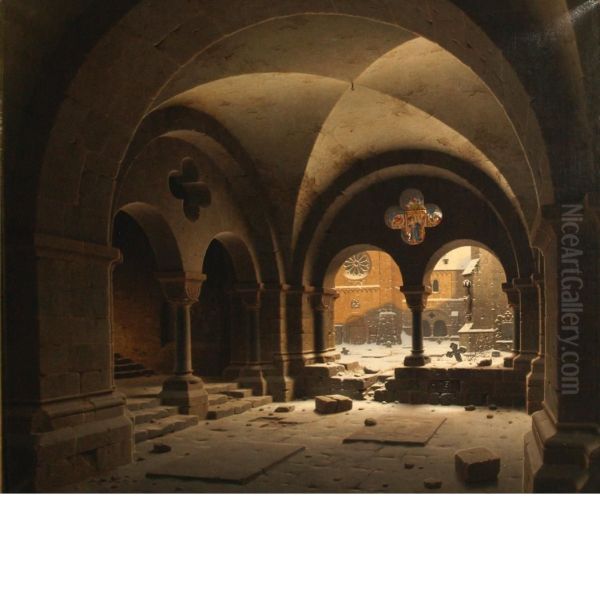

His approach was twofold: he meticulously documented the architectural details of these buildings, demonstrating a keen eye for structure and form, yet he also infused his depictions with a palpable sense of atmosphere and emotion. He was particularly drawn to the effects of light, weather, and the changing seasons on these ancient stones. Snow, mist, twilight, and moonlight often feature in his works, enhancing their melancholic and evocative qualities.

Specialization in Architectural Vedute

Hasenpflug became a specialist in what is known as architectural vedute – highly detailed, large-scale paintings of cityscapes or other vistas. While Italian artists like Canaletto (1697-1768) and Francesco Guardi (1712-1793) had perfected the sunny, picturesque vedute of Venice, German artists adapted the genre to their own national landscapes and historical sensibilities. Painters like Domenico Quaglio II (1787-1837) were also renowned for their precise renderings of Gothic architecture, and Eduard Gaertner (1801-1877) became famous for his detailed views of Berlin. Hasenpflug's work shares this commitment to accuracy but often carries a more pronounced Romantic weight.

He traveled extensively throughout Germany to study and sketch his subjects. Magdeburg and Halberstadt, with their impressive cathedrals and monastic remains, became particularly favored locations. He would make detailed preliminary drawings on site, which then formed the basis for his oil paintings completed in the studio. This practice allowed for both topographical accuracy and artistic interpretation.

Masterpieces of Mood and Detail

Several of Hasenpflug's works stand out as quintessential examples of his style and thematic concerns.

One of his most famous subjects is the Halberstadt Cathedral. He painted it numerous times, often under a blanket of snow. A notable example is "Snowdrifts in the Cloister of Halberstadt Cathedral" (often titled variations like "Ruins of Halberstadt Cathedral in Winter" or "Cloister of the Halberstadt Cathedral in Winter"). These paintings typically depict the Gothic arches and tracery of the cloister partially buried in snow, with a cool, diffused light filtering through. The snow serves not only as a picturesque element but also emphasizes the silence, desolation, and enduring strength of the ancient structure against the harshness of nature. The meticulous rendering of the stonework, the delicate patterns of the frost, and the subtle gradations of white and grey create a scene of profound stillness and introspection.

Another significant work is "Monastery Ruins in Winter with a View of Walkenried Monastery" (Klosterruine im Winter mit Blick auf Kloster Warkenried), painted around 1842. This piece again showcases his fascination with ruins and the winter landscape. The skeletal remains of the monastery, set against a cold sky, evoke a sense of history and decay, yet also a solemn beauty. The interplay of light and shadow across the snow-covered ground and crumbling walls is masterfully handled, creating a scene that is both realistic and deeply poetic.

His depiction of "Cologne Cathedral" (Der Kölner Dom im Jahr seiner Vollendung, 1834-36) is also noteworthy. At the time Hasenpflug painted it, the cathedral was still incomplete (its construction spanned from 1248 to 1880). His paintings of Cologne Cathedral often documented its state during the ongoing construction or highlighted its Gothic grandeur. These works also reflect the 19th-century revival of interest in completing the cathedral, a project that became a symbol of German national unity and cultural pride.

Other important works include views of Magdeburg Cathedral, the churches of Erfurt, and various other medieval sites. He was adept at capturing the vastness of their interiors, the intricate details of their facades, and their integration into the surrounding landscape. His paintings often include small human figures, which serve to emphasize the scale of the architecture and to add a touch of human presence, perhaps contemplation or worship, within these grand spaces.

Technique and Artistic Vision

Hasenpflug's technique was characterized by fine brushwork and a careful layering of glazes to achieve luminosity and depth. His architectural rendering was precise, almost to the point of being photographic, yet he avoided a sterile, purely topographical approach. He understood how to use light to model form, create atmosphere, and direct the viewer's eye. The cool, silvery light of winter was a particular forte, allowing him to explore a subtle palette of blues, greys, and whites, often punctuated by the warmer tones of aged stone.

His compositions were carefully constructed, often using strong diagonal lines or framing devices like archways to lead the viewer into the scene. He masterfully balanced large architectural masses with delicate details, creating a sense of both monumentality and intimacy.

Beyond mere depiction, Hasenpflug's paintings convey a sense of the genius loci, the spirit of the place. The ruins are not just picturesque backdrops; they are imbued with history, memory, and a sense of the sacred. They speak of a past that, while lost, continues to resonate in the present. This aligns with the Romantic preoccupation with the fragment, the ruin as a symbol of both loss and enduring presence.

Professional Life, Patronage, and Connections

In 1828, Carl Hasenpflug married Maria Ruprecht, and by the 1830s, he was establishing himself as both an architect and a painter in Berlin. While his architectural practice is less documented than his painting career, his deep understanding of building construction is evident in his artwork.

The continued support of the Prussian monarchy, particularly from King Frederick William IV (who ascended the throne in 1840), was significant. Frederick William IV was known as the "Romantic on the Throne" and had a keen interest in art and architecture, especially the Gothic style. This royal patronage likely provided Hasenpflug with commissions and opportunities. The provided information suggests that this support extended to studies at the "Roman Art Academy," which could refer to a period of study in Rome, a common aspiration for artists, or perhaps support for engaging with Roman (classical) or Romanesque architectural studies, though his primary focus remained Gothic. It's also possible it refers to German art academies that followed Roman academic traditions.

During his career, Hasenpflug would have interacted with other artists within the Berlin and broader German art scenes. His connection with Schinkel was formative. He would also have been aware of the work of the Nazarenes, a group of German Romantic painters based in Rome (like Friedrich Overbeck and Franz Pforr) who sought to revive spirituality in art by emulating early Italian Renaissance and German medieval masters. While Hasenpflug's style was distinct, the Nazarene emphasis on historical and religious themes resonated with the broader Romantic ethos.

A significant encounter mentioned is with the Romantic poet Friedrich Rellstab (not Lersch, as sometimes misremembered; Ludwig Rellstab was a prominent Berlin-based poet and music critic) in Cologne. This interaction reportedly inspired Hasenpflug to explore aspects of the Düsseldorf School of painting. The Düsseldorf School, led by figures like Wilhelm von Schadow, was a major center for German Romantic and historical painting, known for its detailed execution and often narrative or allegorical content. Artists like Andreas Achenbach (1815-1910) and Oswald Achenbach (1827-1905) became famous for their dramatic landscapes and seascapes, while Johann Wilhelm Schirmer (1807-1863) was influential as a landscape painter and teacher there. Hasenpflug's engagement with the Düsseldorf style might have reinforced his commitment to detailed realism combined with Romantic atmosphere.

Concern for Historical Preservation

Hasenpflug's meticulous depictions of historical buildings also reflect a growing concern for their preservation during the 19th century. Many medieval structures had fallen into disrepair or were threatened by modernization. The Romantic fascination with the past fueled efforts to study, restore, and protect these architectural treasures. Hasenpflug's paintings served not only as artistic creations but also as valuable historical documents.

The information notes his involvement in creating comparative drawings for the restoration of a Gothic church in Berlin, showing its state before and after restoration. This practical application of his skills underscores his commitment to architectural heritage. His work can be seen as part of a broader movement that included architects like Schinkel, who were involved in both creating new buildings in historical styles and restoring existing ones, and art historians who began systematically studying and cataloging medieval art.

Later Years and Death in Halberstadt

In the later part of his career, Hasenpflug moved from Berlin to Halberstadt in 1838, a city whose cathedral and medieval architecture had long been a central focus of his art. This move allowed him to be in even closer proximity to his beloved subjects. He continued to paint, refining his style and exploring new variations on his favorite themes.

Carl Georg Adolph Hasenpflug passed away in Halberstadt on April 13, 1858, at the age of 55. He left behind a significant body of work that captured the essence of Germany's medieval architectural heritage through a Romantic lens.

Legacy and Influence

Carl Hasenpflug is considered one of the foremost German architectural painters of the Romantic era. His works are valued for their technical skill, their atmospheric power, and their historical significance. While perhaps not as widely known internationally as Caspar David Friedrich or Karl Friedrich Schinkel, his contribution to German art is undeniable.

His paintings are held in numerous public and private collections, including major German museums like the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the Kulturhistorisches Museum Magdeburg, and the Städtisches Museum Halberstadt. The enduring appeal of his work lies in its ability to transport the viewer to a different time, to evoke a sense of wonder at the grandeur of Gothic architecture, and to stir a melancholic appreciation for the passage of time.

He influenced a subsequent generation of architectural painters in Germany. Artists like Eduard Gießner and Heinrich Hinze are mentioned as having been inspired by his approach. His meticulous yet evocative style set a standard for the depiction of historical architecture.

In recognition of his artistic contributions and his deep connection to the cities he painted, streets in Halberstadt and Magdeburg have been named in his honor (Hasenpflugstraße). This serves as a lasting tribute to an artist who dedicated his life to chronicling the stone monuments of Germany's past.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Carl Georg Adolph Hasenpflug was more than just a painter of buildings; he was a poet of stone and light. His canvases capture the solemn majesty of Gothic cathedrals, the poignant beauty of their ruins, and the subtle moods of the German landscape. He successfully merged the precision of an architect's eye with the soul of a Romantic painter, creating works that are both topographically accurate and emotionally resonant.

In an era that rediscovered and romanticized the Middle Ages, Hasenpflug provided a visual language for this fascination. His paintings of Halberstadt, Magdeburg, Cologne, and other historic sites remain powerful testaments to the enduring allure of Gothic architecture and the profound spiritual and historical associations it held for the Romantic imagination. His legacy is that of an artist who not only preserved the likeness of these structures but also captured their very soul, ensuring that their silent, stony grandeur continues to speak to viewers today. His work remains a vital part of the rich tapestry of German Romantic art, offering a unique window into the 19th-century's engagement with its medieval heritage.