Augustus Charles Pugin stands as a significant, if sometimes overshadowed, figure in the history of British art and architecture. A multi-talented individual, he excelled as an architectural draughtsman, illustrator, watercolourist, designer, and influential teacher. While his son, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, would go on to achieve even greater fame as a polemicist and architect of the High Gothic Revival, it was the elder Pugin who laid much of the essential groundwork. His meticulous documentation of medieval buildings provided an invaluable resource for a generation of architects and designers, fueling the burgeoning interest in Gothic forms during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Early Life and Flight to England

Born Auguste Charles Pugin, likely in Paris, in 1769 (though some earlier sources suggest 1762), his early life was shaped by the tumultuous events of his era. Details about his family background are somewhat varied, with some accounts suggesting noble lineage and others pointing to a Swiss connection, possibly through service in the Swiss Guard. What is clear is that the French Revolution (1789-1799) profoundly impacted his trajectory. Like many others fearing for their safety or prospects, Pugin made the decision to leave France. He arrived in London around 1792, an émigré seeking refuge and new opportunities.

This move to England marked a pivotal turning point. London, at the time, was a vibrant hub of artistic and intellectual activity. For a young man with artistic inclinations, it offered a stimulating environment. Pugin's French background, coupled with his inherent talents, would soon find an outlet in the British capital.

Education and Early Career in London

Upon settling in London, Augustus Charles Pugin sought to formalize his artistic training. He enrolled as a student at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1792. The Royal Academy, founded by luminaries such as Sir Joshua Reynolds, was the foremost institution for art education in Britain. Here, Pugin would have been immersed in the classical traditions of drawing and design, honing his skills alongside other aspiring artists. During his time at the Academy, he formed acquaintances with figures who would also make their mark, such as the future President of the Royal Academy, Martin Archer Shee, and the historical painter William Hilton.

A significant encounter from his past also occurred in London: he reconnected with a fellow Frenchman and watercolourist named Mérigot. Such connections within the émigré community and the broader artistic circles were vital for establishing a career. Pugin's talent as a draughtsman did not go unnoticed. He found employment in the busy architectural office of John Nash, one of the most prominent and prolific architects of the Regency era.

Working with John Nash

Working for John Nash provided Pugin with invaluable practical experience. Nash's office was responsible for some of the most ambitious urban planning and architectural projects of the time, including Regent Street and Regent's Park in London, and the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. As a draughtsman for Nash, Pugin would have been involved in preparing detailed architectural drawings, perspectives, and presentation pieces. This role demanded precision, an understanding of architectural forms, and the ability to create visually appealing renderings.

While Nash was known for his Picturesque and Neoclassical styles, and even dabbled in Chinoiserie and Indian-inspired designs, his office would have exposed Pugin to a wide range of architectural vocabularies. This period undoubtedly sharpened Pugin's technical skills and his eye for architectural detail, which would become hallmarks of his later work. It was also during this time that he began to develop his distinct proficiency in architectural watercolour.

The Master Architectural Draughtsman and Watercolourist

Augustus Charles Pugin developed a remarkable skill in architectural illustration. His drawings were characterized by their accuracy, clarity, and delicate yet effective use of watercolour. He played a role in the evolution of architectural rendering, moving away from the lightly tinted drawings of earlier periods towards a fuller, more atmospheric use of colour. This enhanced the descriptive power of his illustrations, making ancient buildings come alive for his audience.

His abilities were not confined to merely recording structures; he possessed an artist's eye for composition and light, lending an aesthetic appeal to his works that went beyond simple documentation. This combination of precision and artistry made his illustrations highly sought after and incredibly influential. He understood that to revive Gothic architecture, one first needed to understand it thoroughly, and his drawings became a primary means of disseminating this understanding.

Key Publications: Documenting the Gothic Past

Perhaps Augustus Charles Pugin's most enduring legacy lies in his series of illustrated books on Gothic architecture. These publications were instrumental in providing architects, builders, and patrons with accurate and detailed examples of medieval design, at a time when such resources were scarce.

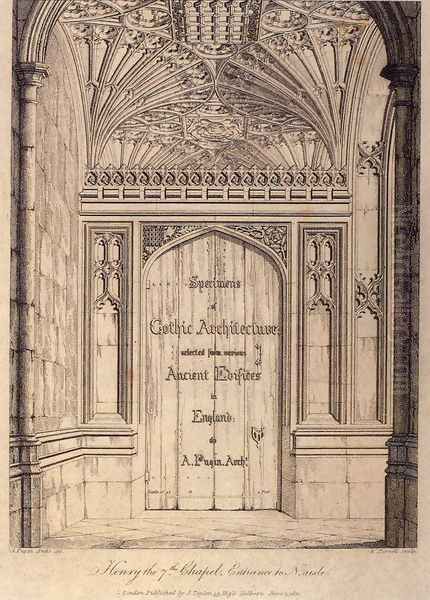

Specimens of Gothic Architecture

Published in two volumes between 1821 and 1823, Specimens of Gothic Architecture; Selected from Various Antient Edifices in England was a landmark work. Pugin collaborated with the antiquary Edward James Willson, who provided the historical and descriptive text. The volumes contained numerous meticulously engraved plates, based on Pugin's own drawings and those of his pupils. These plates showcased a wide array of Gothic elements: arches, windows, doorways, mouldings, vaulting, and ornamentation, all carefully measured and drawn to scale.

Specimens became an indispensable pattern book for architects involved in the Gothic Revival. It offered a reliable grammar of Gothic forms, allowing designers to move beyond the often fanciful and inaccurate "Gothick" of the 18th century towards a more archaeologically informed approach. Architects like Charles Barry (who would later collaborate with Pugin's son on the Houses of Parliament) and many others would have consulted these volumes extensively.

Examples of Gothic Architecture

Following the success of Specimens, Pugin, along with his son A.W.N. Pugin and other assistants like Thomas Larkins Walker, produced Examples of Gothic Architecture; Selected from Various Antient Edifices in England (1828-1831, with later volumes). This series continued the work of documenting medieval buildings with the same attention to detail and high-quality illustration. It further expanded the repertoire of Gothic forms available to contemporary practitioners.

These books were not just academic exercises; they were practical tools. They provided a visual encyclopedia that architects could draw upon for inspiration and for the correct application of Gothic details in new buildings, whether churches, country houses, or public institutions. The influence of these publications on the visual character of 19th-century Britain cannot be overstated.

Architectural Antiquities of Normandy

Pugin also turned his attention to the Gothic architecture of France, particularly Normandy, which had close historical and architectural ties to England. Working with John Britton, a prominent antiquarian and publisher, and his son A.W.N. Pugin, he produced Architectural Antiquities of Normandy (1827-1828). This work, featuring text by Britton and exquisite plates after drawings by Pugin and his team, introduced British architects to the richness and distinct characteristics of Norman Gothic. It highlighted the early development of Gothic features and provided another stream of authentic medieval precedent.

Other important illustrative projects included contributions to Rudolph Ackermann's Microcosm of London (1808-1810), where Pugin provided the architectural backgrounds for figures drawn by Thomas Rowlandson. This showcased his versatility and his ability to collaborate with other artists. He also contributed to Ackermann's Repository of Arts, a highly influential periodical.

Architectural Practice and Teaching

While Augustus Charles Pugin is primarily remembered for his publications and illustrations, he also maintained an architectural office and drawing school in his home at 105 Great Russell Street. This school became a significant training ground for a new generation of architects and architectural draughtsmen. He was a dedicated teacher, imparting his meticulous methods and his passion for Gothic architecture to his students.

Among his pupils were figures who would go on to have successful careers, including Benjamin Ferrey (who later became a biographer of A.W.N. Pugin), Joseph Nash (known for his picturesque views of old English mansions, not to be confused with John Nash), and Thomas Talbot Bury. Bury, in particular, became a close associate, assisting Pugin with his publications and later becoming an architect and lithographer in his own right, often engraving Pugin's work.

Pugin's own built architectural work is less prominent than his illustrative output. He was involved in some design projects, often in collaboration or as a consultant, particularly for interior schemes and Gothic detailing. However, his primary impact as an "architect" was arguably through the designs he enabled others to create via his books and his teaching.

The Pugin Dynasty: Father and Son

It is impossible to discuss Augustus Charles Pugin without mentioning his son, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-1852). A.W.N. Pugin was a prodigy, deeply influenced by his father's work and passion for the Gothic. He rapidly surpassed his father in terms of architectural output and, crucially, in theoretical and polemical impact.

While A.C. Pugin was the careful documenter and teacher, A.W.N. Pugin became the fervent apostle of the Gothic Revival. He believed Gothic was not merely a style but the only true Christian form of architecture. His influential books, such as Contrasts (1836) and The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (1841) – the latter often mistakenly attributed in passing to his father in some summaries – articulated a moral and religious basis for the Gothic Revival that transformed the movement.

A.W.N. Pugin's life was intense and tragically short. He converted to Roman Catholicism in 1834, a decision that deeply influenced his work and patronage, leading him to design numerous Catholic churches. His collaboration with Sir Charles Barry on the design of the New Palace of Westminster (the Houses of Parliament) is legendary, with A.W.N. Pugin being responsible for much of its intricate Gothic detailing and interior design. The exact nature and extent of his contribution became a point of contention, with Barry's family downplaying Pugin's role after his death, while Pugin's supporters championed his creative genius. A.W.N. Pugin also faced personal tragedies, including multiple marriages ending in widowhood, financial struggles, and deteriorating mental health, leading to his death at the young age of 40.

The elder Pugin provided the foundational knowledge and the visual tools; the younger Pugin weaponized this knowledge with passionate conviction and prodigious design talent, pushing the Gothic Revival into its High Victorian phase. The father's careful archaeological approach paved the way for the son's more ideological and creative interpretation.

Artistic Style and Lasting Contributions

Augustus Charles Pugin's artistic style was characterized by precision, clarity, and an understated elegance. His watercolours, while becoming richer in tone over time, always served the primary purpose of accurately conveying architectural form. He understood the importance of light and shadow in defining three-dimensional space and used these elements effectively.

His contributions were manifold:

1. Systematic Documentation: He was among the first to systematically measure, draw, and publish detailed studies of English (and Norman) Gothic architecture, making authentic medieval forms accessible.

2. Educational Impact: Through his publications and his drawing school, he trained and influenced a significant number of architects and draughtsmen who would carry the Gothic Revival forward. His books served as essential textbooks.

3. Elevating Architectural Illustration: He raised the standard of architectural illustration, combining technical accuracy with artistic sensitivity.

4. Facilitating the Gothic Revival: His work provided the practical and visual toolkit that enabled the shift from the whimsical "Gothick" of the 18th century to a more historically informed and serious Gothic Revival in the 19th century.

Contemporaries and Collaborators

Beyond John Nash and his own students, A.C. Pugin operated within a rich artistic and antiquarian milieu. His collaboration with John Britton on the Architectural Antiquities of Normandy and other works like Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain (to which Pugin contributed plates) was significant. Britton was a key figure in popularizing English antiquities. Edward Wedlake Brayley was another antiquarian writer with whom Britton, and by extension Pugin, often worked.

In the wider London art world, figures like Sir John Soane were pushing architectural boundaries in Neoclassicism, while painters like J.M.W. Turner and Thomas Girtin were revolutionizing watercolour painting, taking it to new heights of expressive power. While Pugin's focus was more documentary, the general elevation of watercolour as a medium would have been part of the artistic air he breathed. His acquaintances from the Royal Academy, Martin Archer Shee and William Hilton, pursued careers in portraiture and historical painting respectively.

The collaborative nature of publishing at the time meant Pugin also worked closely with engravers who translated his drawings into printable plates, a crucial step in disseminating his work widely.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

Augustus Charles Pugin continued his work as an illustrator and teacher into his later years. He saw his son, A.W.N. Pugin, begin his meteoric rise, building upon the foundations he had laid. The elder Pugin passed away on December 19, 1832, in London, at his home in Great Russell Street. He was buried in the churchyard of St. Mary's, Islington.

His death occurred just as the Gothic Revival was gathering serious momentum, a movement he had done so much to nurture. While his son would become the more celebrated name, A.C. Pugin's contribution was fundamental. He provided the scholarly underpinning and the visual resources that made the subsequent flowering of Gothic Revival architecture possible. Architects like George Gilbert Scott, William Butterfield, and countless others who shaped the Victorian landscape owed a debt to the meticulous groundwork laid by Augustus Charles Pugin. His influence extended beyond Britain, as his books were also known in America and continental Europe, inspiring interest in Gothic forms there as well.

John Ruskin, the great Victorian art critic and theorist, would later champion Gothic from a different, more philosophical perspective than A.W.N. Pugin, but the detailed knowledge of the style that both Pugins helped to codify was essential for the very debates and developments Ruskin engaged with.

Conclusion: The Quiet Enabler of a Movement

Augustus Charles Pugin may not have designed as many buildings as his son, nor did he write fiery manifestos. His was a quieter, more scholarly contribution. Yet, through his dedication to the accurate recording and dissemination of Gothic architectural knowledge, he played an indispensable role. He was an enabler, providing the tools and the training that allowed the Gothic Revival to flourish. His books remain valuable historical documents and testaments to his skill as a draughtsman and his importance as an educator. As an art historian, one must recognize him as a key transitional figure, bridging the gap between the antiquarian interest of the 18th century and the full-blooded architectural movement of the 19th, ensuring that the revival of Gothic forms was grounded in a genuine understanding of its historical precedents. His legacy is etched not only in the pages of his influential publications but also in the very fabric of countless 19th-century buildings that drew inspiration from his work.