Carlo Dolci stands as one of the most significant painters of the Florentine Baroque period. Active during the 17th century, an era marked by profound religious feeling and artistic innovation, Dolci carved a unique niche for himself with his intensely devotional paintings and meticulously rendered portraits. His work, characterized by its smooth finish, delicate colouring, and profound emotional depth, earned him immense popularity during his lifetime, particularly among the powerful Medici family and devout patrons across Europe. Though his reputation fluctuated in subsequent centuries, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized his technical brilliance and his distinct contribution to the artistic landscape of Seicento Florence.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Carlo Dolci was born in Florence on May 25, 1616. Details about his immediate family background are somewhat scarce, but it is known that his grandfather was also a painter. This familial connection to the arts may have predisposed the young Carlo towards a similar path. His artistic journey began in earnest at the tender age of nine when he entered the bustling workshop of Jacopo Vignali, a respected Florentine painter. Vignali was known for his expressive figures, elegant compositions, and a vibrant use of colour, traits that would leave a lasting impression on his young pupil.

Under Vignali's guidance, Dolci received a thorough grounding in the fundamentals of drawing and painting, absorbing the prevailing Florentine taste for clarity of design and refined execution. The Florence of the early 17th century still bore the strong imprint of its Renaissance heritage, valuing draftsmanship and compositional harmony. Vignali himself was part of a lineage that looked back to artists like Matteo Rosselli. Dolci quickly proved to be a prodigious talent, mastering the techniques taught by his master.

Beyond the direct tutelage of Vignali, the young Dolci immersed himself in the rich artistic environment of Florence. He is known to have diligently studied and copied the works of earlier masters. Sources suggest he spent time analyzing the paintings of Fra Angelico, whose pure colours and serene spirituality likely resonated with Dolci's own pious temperament. He also looked towards the High Renaissance giants, reportedly copying works by Michelangelo, known for his powerful figures and anatomical mastery, and Raphael, admired for his grace and harmonious compositions. The influence of Correggio, a master of soft light and tender emotion from Parma, is also cited as formative for Dolci's developing style. This practice of copying was standard artistic training, allowing young painters to understand composition, technique, and form by emulating established masters.

The Emergence of a Distinctive Style

Building upon the foundation laid by his training and studies, Carlo Dolci developed a highly personal and instantly recognizable artistic style. His approach was marked by an extraordinary meticulousness and a quest for technical perfection. He became renowned for his incredibly smooth, enamel-like finish, often achieved through the laborious application of thin glazes of oil paint. This technique, known as finitura, lent his works a precious, jewel-like quality, devoid of visible brushstrokes, which greatly appealed to collectors.

Dolci's palette was typically soft and harmonious, favouring rich but controlled colours. He masterfully employed chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow – but unlike the stark, theatrical contrasts seen in the work of Caravaggio and his followers, Dolci's use of light was generally softer, serving to model forms gently and create an atmosphere of quiet intimacy and divine radiance. Light often falls strategically, illuminating a face, hands, or a significant object, drawing the viewer's focus to the emotional or spiritual core of the scene.

A key characteristic of Dolci's art is its profound sense of piety and intense religious sentiment. Living and working in the wake of the Counter-Reformation, a period when the Catholic Church sought to reaffirm its doctrines and inspire faith through art, Dolci dedicated much of his output to religious themes. He approached these subjects with deep personal conviction, aiming, as his biographer Filippo Baldinucci noted, to inspire Christian piety in the viewer. His figures, whether Christ, the Virgin Mary, or saints, are often depicted in moments of intense prayer, sorrow, or ecstasy, their faces imbued with a palpable, often tearful, emotion.

Some scholars suggest Dolci may have also been influenced by Northern European painting, possibly Dutch art, which was known for its detailed realism and fine finish. While direct evidence of studying Dutch techniques is debated, the meticulous rendering of textures – silks, velvets, jewels, and flowers – in his portraits and still lifes certainly shares an affinity with the Northern tradition, perhaps exemplified by artists like Gerrit Dou. He also utilized preparatory drawing techniques common in Florence, including the use of red and black chalk, to carefully plan his compositions before transferring them to canvas or panel.

Sacred Themes: Images of Devotion

The vast majority of Carlo Dolci's oeuvre consists of religious paintings, reflecting both his personal piety and the demands of his patrons. He became particularly famous for his half-length or bust-length depictions of single figures, designed for private devotion. These intimate portrayals allowed viewers to engage directly with the sacred subject on an emotional level.

His representations of the Virgin Mary were especially popular. He painted numerous versions of the Mater Dolorosa (Sorrowful Mother), often showing Mary with eyes cast heavenward, tears welling or streaming down her cheeks, her expression a mixture of profound grief and resigned acceptance. A notable example resides in the Louvre Museum in Paris. These images, executed with exquisite refinement, captured the pathos of Mary's suffering in a way that deeply moved contemporary audiences. He also painted serene images of the Madonna and Child, emphasizing the tender bond between mother and son.

Christ was another central figure in Dolci's work. He depicted Christ carrying the cross, the Ecce Homo (Christ presented to the crowd by Pilate), and Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World). These paintings often focus closely on Christ's face, highlighting his suffering, compassion, or divine authority through subtle expressions and the careful rendering of features like the crown of thorns or drops of blood, all executed with Dolci's characteristic smooth finish. The Descent of the Holy Spirit on Christ, dated 1666 and held in the Grand Ducal Collections in Florence, showcases his ability to handle more complex compositions while maintaining his focus on spiritual intensity.

Dolci also painted numerous saints, often choosing figures known for their intense faith or mystical experiences. His Saint Andrew Praying Before the Cross (1646), housed in the Pitti Palace, Florence, is a powerful early work depicting the apostle in fervent prayer before his martyrdom. The dramatic lighting and the saint's rapt expression are characteristic of Dolci's ability to convey deep spiritual states. Another significant work is The Evangelist St. John Writing, with a version located in Berlin, showing the saint receiving divine inspiration. His portrayal of St. Philip Neri, the founder of the Oratorians known for his piety and charitable work in Rome, painted around 1645-46 (versions exist, including one in the Pitti Palace), further demonstrates his skill in capturing the essence of saintly figures.

Mastery in Portraiture and Still Life

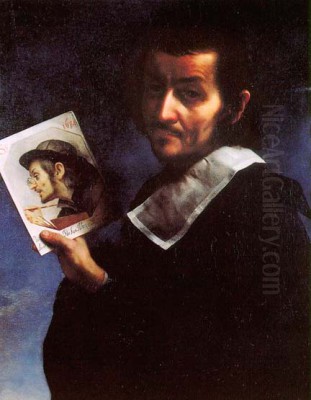

While primarily celebrated for his religious works, Carlo Dolci was also an accomplished portraitist and a capable painter of still lifes. His portraits, like his sacred images, are characterized by meticulous detail, a smooth finish, and a sensitive rendering of the sitter's likeness and, often, their inner state. He received commissions from prominent members of Florentine society and visiting dignitaries.

One of his earliest known portraits is the Portrait of Fra Ainolfo dei Bardi (1632), also in the Pitti Palace. This work, painted when Dolci was only sixteen, already displays his remarkable technical skill and ability to capture a sense of presence. He meticulously renders the textures of the friar's habit and the details of his face, conveying a sense of quiet dignity. Throughout his career, he painted portraits of members of the Medici family and other notable figures, often embedding subtle indicators of status or piety within the composition.

Dolci's skill extended to the genre of still life, although fewer examples survive compared to his religious output. His Still Life: Vase with Flowers (1662), now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, is a testament to his abilities in this area. The painting depicts a vibrant bouquet featuring tulips, hyacinths, anemones, and other flowers, rendered with astonishing realism. Each petal and leaf is captured with botanical accuracy and exquisite detail, showcasing Dolci's keen observational skills and his mastery of colour and texture. The luminous quality of the paint application brings the flowers vividly to life against a dark background. This attention to detail in depicting natural elements, as well as luxurious items like jewelry and rich fabrics, was a hallmark that carried across all genres he worked in.

Patronage, Career, and Reputation

Carlo Dolci's career flourished largely within the confines of his native Florence, where he enjoyed significant patronage, most notably from the ruling Medici family. Cardinal Leopoldo de' Medici, a discerning collector and patron of the arts, was an early and important supporter. Dolci's meticulously finished, emotionally resonant works perfectly suited the tastes of the later Medici Grand Dukes and their court, who valued refinement and piety. His connection to the Medici provided him with prestigious commissions and ensured his prominence within the Florentine art world. Other patrons included figures like the musician Antonio Landini.

Despite his success, Dolci seems to have been a somewhat retiring figure. According to his biographer Baldinucci, he rarely left Florence. His one documented trip abroad was to Innsbruck, likely in the 1670s, at the invitation of Anna de' Medici, wife of Archduke Ferdinand Charles of Austria. During this visit, he painted portraits of the Archduchess and her daughter, Claudia Felicitas, who would later marry Emperor Leopold I. This journey highlights the reach of his reputation beyond Tuscany.

Dolci's fame spread throughout Italy and even internationally. His works were highly sought after by collectors, including British aristocrats undertaking the Grand Tour in the 18th century, who admired the technical perfection and devotional intensity of his paintings. His reputation during his lifetime was exceptionally high, and he was considered one of Florence's leading masters. The demand for his work was such that he, or his workshop, produced replicas of his most popular compositions to satisfy collectors.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Carlo Dolci worked during a vibrant period in Italian art history, though Florence's artistic prominence was arguably waning compared to the dynamism of Rome. His teacher, Jacopo Vignali, connected him to the established Florentine traditions. Within Florence, other notable artists were active, such as the Flemish-born portraitist Justus Sustermans, who also served the Medici court, and Baldassare Franceschini, known as Il Volterrano, a skilled fresco painter. Dolci's focus on easel painting, particularly small-scale devotional works, set him apart from artists primarily engaged in large decorative schemes.

His meticulous style contrasted sharply with the more painterly and rapid execution favoured by some contemporaries, most famously Luca Giordano. A well-known anecdote, recounted by Baldinucci, describes Dolci falling into a deep melancholy, possibly contributing to his death, after witnessing the Neapolitan painter Giordano (nicknamed "Luca fa presto" or "Luke paints quickly") complete a painting in a matter of hours – a task that would have taken Dolci weeks or months. While the direct causality might be exaggerated, the story highlights the differing artistic temperaments and approaches of the time. Giordano, also patronized by the Medici, represented a more exuberant, virtuosic strain of Baroque painting.

Dolci's art, while distinctly Florentine, can be situated within the broader context of Italian Baroque religious painting. His emphasis on intense emotion and piety aligns with the goals of the Counter-Reformation. His style finds parallels in the work of other artists specializing in devotional imagery, such as Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato, whose serene Madonnas share a certain clarity and smooth finish, though Dolci's work often possesses a greater emotional intensity. Comparisons can also be drawn to the Bolognese painter Guido Reni, whose idealized figures and sentimental religious scenes were immensely popular throughout Europe, though Dolci's technique remained uniquely meticulous. While aware of the innovations of Caravaggio in Rome, Dolci adopted chiaroscuro in a less aggressive, more refined manner suited to his devotional aims.

Anecdotes and Personal Life

Biographical accounts, primarily from Filippo Baldinucci's Notizie de' professori del disegno da Cimabue in qua (Notices of the Professors of Design from Cimabue Onwards), paint a picture of Carlo Dolci as an exceptionally pious, methodical, and perhaps somewhat introverted individual. His deep religious faith permeated his life and art; he reportedly recited prayers while painting and saw his work as a form of worship.

His meticulousness extended to his working habits. He was known to be an extremely slow and painstaking painter, dedicating immense time and effort to achieving the flawless finish for which he was celebrated. This deliberate pace contrasts sharply with the anecdote involving Luca Giordano's rapid execution.

Baldinucci also recounts a curious story regarding Dolci's personal life. Despite his reserved nature, Dolci was apparently pressured into marriage later in life, around the age of 54. The intended bride was Teresa Bucheri. However, on the wedding day, the bride and guests waited at the church, but Dolci failed to appear, leading to the cancellation of the ceremony. Sources differ on whether he ever married; some suggest he remained unmarried, while others mention a wife and children, including his painter daughter. This anecdote, if true, underscores his potentially unconventional or socially awkward personality.

Towards the end of his life, Dolci is said to have suffered from depression or melancholy. The encounter with Giordano is often cited as a trigger, highlighting a potential insecurity about his own laborious methods in an age that sometimes valued speed and bravura. Baldinucci suggests he experienced dark thoughts and perhaps psychological distress in his final years. Carlo Dolci died in Florence on January 17, 1687, at the age of 70.

Workshop, Legacy, and Followers

Like many successful artists of his time, Carlo Dolci likely maintained a workshop to assist with commissions and replicas. While details about its operation are limited, the demand for his work suggests the need for assistants. His most notable follower was undoubtedly his own daughter, Agnese Dolci (died c. 1686 or 1689, dates vary). Agnese was a talented painter in her own right, trained by her father and adopting his meticulous style and preferred subject matter.

Agnese Dolci became known for producing faithful copies of her father's most popular works, helping to meet the high demand from collectors. She also created original compositions in a similar vein. Her skill was such that distinguishing her work from her father's can sometimes be challenging for art historians. Other recorded pupils or followers include artists named Loma, Alessandro Mariani, and Bartolomeo Mancini, though less is known about their individual careers and contributions. Dolci's influence primarily manifested through the enduring popularity of his specific style of devotional painting and the numerous copies and imitations produced by his followers and later artists.

Critical Reception Through the Centuries

Carlo Dolci's art enjoyed immense popularity during his lifetime and throughout the 18th century. His works were prized possessions in royal and aristocratic collections across Europe. Grand Tourists, particularly from Britain, eagerly acquired his paintings, drawn to their technical perfection, refined beauty, and palpable piety. His name became synonymous with a certain type of highly finished, emotionally charged religious art.

However, by the 19th century, critical tastes began to shift. The rise of Romanticism and later Realism led to a re-evaluation of Baroque art. Dolci, in particular, came under criticism for what was perceived as excessive sentimentality, sweetness, and overt piety. Influential critics like John Ruskin, who championed more robust and less overtly polished styles, dismissed Dolci's work as affected and lacking in genuine spiritual depth. His meticulous finish was sometimes seen as laborious rather than skillful, and his emotionalism as saccharine. Consequently, his reputation declined significantly, and he was often relegated to the status of a minor master, representative of a decadent phase of Italian art.

The 20th century saw periods of continued neglect, but also the beginnings of a scholarly reassessment. Art historians began to look beyond the critiques of sentimentality to appreciate Dolci's exceptional technical skill, his unique position within the Florentine Baroque, and the genuine religious conviction that informed his work. His art was re-examined within the context of Counter-Reformation spirituality and patronage, leading to a more nuanced understanding of his aims and achievements.

Modern Recognition: Exhibitions and Scholarship

In recent decades, Carlo Dolci has experienced a significant revival of interest, spearheaded by new scholarship and major exhibitions. These initiatives have sought to re-evaluate his contribution and present his work to a wider audience, moving beyond outdated criticisms.

A landmark event was the exhibition "Carlo Dolci: 1616-1687" held at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence in 2015. This major retrospective brought together over seventy works by the artist, offering an unprecedented opportunity to study his development and appreciate the range and quality of his output in his native city.

Two years later, in 2017, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College in Massachusetts mounted "The Medici's Painter: Carlo Dolci and 17th-Century Florence." This was the first monographic exhibition dedicated to Dolci in the United States. Featuring over fifty works, including significant loans from the Uffizi Gallery, the Pitti Palace, the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and private collections, the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue explored Dolci's art in depth, examining his technique, his relationship with the Medici court, and the global circulation of his imagery. The catalogue, titled Beyond Sentimentality: Carlo Dolci and 17th-Century Florence, provided important new research and perspectives.

Recent publications, such as Amy Fredrickson's 2022 study Carlo Dolci: The Art of Devotion, have further contributed to a deeper understanding of the artist's life, work, and legacy. These scholarly efforts have helped to reposition Dolci not merely as a painter of sweet Madonnas, but as a master technician, a profound interpreter of religious emotion, and a key figure in the twilight of Florence's artistic golden age. His works continue to be admired in major museums worldwide, including the National Gallery in London, the Vatican Museums in Rome, and numerous institutions across Europe and North America.

Conclusion: The Enduring Art of Carlo Dolci

Carlo Dolci occupies a unique and significant place in the history of Italian art. As arguably the last great master of the Florentine Baroque, he brought the city's long tradition of refined draftsmanship and technical precision to a peak of almost unbelievable meticulousness. His art, deeply rooted in personal faith and the religious currents of the Counter-Reformation, aimed to stir the souls of its viewers through images of intense piety and exquisite beauty.

While his highly finished style and overt emotionalism led to criticism in later eras, the pendulum of taste has swung back towards a greater appreciation of his undeniable skill and the specific historical and spiritual context in which he worked. His luminous surfaces, delicate colours, and the quiet, often sorrowful, intensity of his figures continue to captivate. Whether admired for their technical brilliance, their devotional power, or their distinct place within the tapestry of Baroque art, the paintings of Carlo Dolci endure as testaments to a unique artistic vision pursued with unwavering dedication and extraordinary skill. His legacy is that of a master who, through piety and precision, created some of the most memorable and finely wrought images of his time.