Francesco Zuccarelli stands as one of the most celebrated and internationally successful Italian landscape painters of the 18th century. Flourishing during the late Baroque and Rococo periods, he crafted idyllic, pastoral scenes that captured the imagination of patrons across Europe, particularly in Great Britain. Born in Tuscany, trained in Rome and Florence, and achieving fame in Venice and London, Zuccarelli's career exemplifies the cosmopolitan nature of the European art world in his time. His gentle, light-filled canvases, populated with elegant peasants and set within idealized Arcadian landscapes, offered a charming counterpoint to the grand history painting or the precise topographical views favoured by some contemporaries. His influence extended beyond his canvases, contributing significantly to the founding of London's Royal Academy of Arts and shaping the taste for landscape painting among British collectors and artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Francesco Zuccarelli was born in 1702 in Pitigliano, a small town nestled in the southern part of Tuscany, Italy. His initial artistic inclinations led him towards formal training, a journey that took him first to Florence and then to the vibrant artistic centre of Rome. In Rome, the young artist immersed himself in the study of painting, seeking guidance from established masters. His principal teachers during this formative period included Paolo Anesi, a landscape painter known for his Roman views, and Giovanni Maria Morandi, a respected painter whose oeuvre encompassed portraiture and historical subjects, providing Zuccarelli with a broad technical foundation.

During his time in Rome, Zuccarelli inevitably absorbed the pervasive influence of the great 17th-century classical landscape tradition. The works of French masters Nicolas Poussin and, most significantly, Claude Lorrain, cast a long shadow over landscape painting throughout Europe. Lorrain's idealized visions of the Roman Campagna, bathed in golden light and imbued with a sense of nostalgic poetry, profoundly shaped the aesthetic sensibilities of the era. Zuccarelli learned from Lorrain's compositional strategies, his handling of light, and his creation of harmonious, Arcadian worlds where nature and humanity coexist peacefully. This classical grounding would remain a cornerstone of Zuccarelli's art, even as he developed his own distinct Rococo sensibility.

Before fully dedicating himself to landscape painting, Zuccarelli explored other artistic avenues. Sources suggest an early period in Florence where he may have engaged in etching and potentially even participated in the restoration of older artworks. This early experience with different techniques likely contributed to his later versatility. However, his true calling lay in depicting the natural world, albeit through a highly refined and idealized lens. The training in Rome, combined with his innate talent, prepared him for the next significant phase of his career in the bustling artistic milieu of Venice. His Florentine training under figures like Pietro Nelli also contributed to his understanding of drawing and composition, further enriching the skills he brought from Rome.

The Venetian Period: Rise to Prominence

Around 1732, Francesco Zuccarelli made a pivotal move to Venice. La Serenissima, at this time, was a dazzling hub of artistic activity, albeit one nearing the end of its golden age as an independent republic. The city boasted a unique artistic environment, distinct from the classical rigour of Rome or the intellectual focus of Florence. Venetian art, particularly during the 18th century, was renowned for its emphasis on colour (colorito), light, and atmospheric effects, characteristics embodied in the works of masters like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo in grand decorative schemes, and Canaletto and Francesco Guardi in their celebrated vedute, or view paintings.

Zuccarelli arrived in a city where the market for art was buoyant, fueled by local patrician families and the increasing number of wealthy foreign visitors undertaking the Grand Tour. While Canaletto and Guardi meticulously documented the city's canals, squares, and ceremonies, Zuccarelli offered something different and highly appealing: charming, idealized landscapes that evoked a sense of pastoral tranquility and escape. His style, evolving from its Roman classical roots, began to incorporate the lighter palette, delicate brushwork, and graceful elegance associated with the prevailing Rococo taste, perfectly suited to the decorative demands of Venetian interiors.

His success in Venice was relatively swift. His landscapes, often featuring gentle hills, meandering streams, picturesque ruins, and elegantly attired shepherds and shepherdesses, found favour with collectors. These were not direct transcriptions of nature but rather poetic inventions, Arcadian fantasies designed to delight the eye and soothe the spirit. The figures in his paintings, often small but essential components of the composition, were rendered with a characteristic Rococo charm and grace.

During his Venetian years, Zuccarelli sometimes collaborated with other prominent artists. Notably, he worked with Antonio Visentini, an architect, painter, and engraver best known for his architectural perspectives and collaborations with Canaletto. In some instances, Visentini might provide the architectural settings within a landscape primarily painted by Zuccarelli, or Zuccarelli might add the figures (staffage) to Visentini's views. He also had connections with Bernardo Bellotto, Canaletto's talented nephew, who himself became a renowned view painter across Europe. Such collaborations were common practice and enriched the artistic output of the period, blending different specialisms. Zuccarelli's growing reputation in Venice laid the groundwork for his future international success.

The British Connection: Patronage and Acclaim

The allure of Italy, and particularly Venice, drew countless British travellers during the 18th century as part of the Grand Tour. This cultural pilgrimage was considered essential for the education and refinement of young noblemen and gentlemen. These visitors were not just sightseers; they were often avid collectors, eager to acquire Italian art as souvenirs and status symbols to adorn their country estates back home. This created a fertile market for artists like Zuccarelli, whose pleasing pastoral style resonated strongly with British tastes, which often favoured landscape and portraiture over grand historical or religious subjects.

A key figure in facilitating Zuccarelli's connection with the British market was Joseph Smith. Smith served as the British Consul in Venice for many years and was a major art collector, patron, and dealer. He played a crucial role in the careers of several artists, most famously Canaletto, whose works he collected extensively and promoted in England. Smith also became an important patron and supporter of Zuccarelli, recognizing the appeal of his landscapes to British sensibilities. It was likely through Smith's network and encouragement that Zuccarelli decided to travel to England.

Zuccarelli made two extended stays in London. The first lasted a decade, from 1752 to 1762, and the second ran from 1765 to 1771. During these periods, he achieved remarkable success. His light, airy, and decorative landscapes proved immensely popular among the British aristocracy and gentry. His patrons included influential figures like Lord Bute and Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont, for whom he painted significant works, including large-scale landscapes for Petworth House in Sussex. His fame reached the highest levels of society, attracting the patronage of King George III himself, who acquired several of his paintings for the Royal Collection, many of which remain at Windsor Castle today.

His standing within the London art establishment was solidified in 1768 when he became one of the founding members of the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts. This honour placed him alongside the leading British artists of the day, such as Sir Joshua Reynolds, the Academy's first president, and Thomas Gainsborough. Although Reynolds was primarily a portraitist and theorist, and Gainsborough developed a more naturalistic landscape style, both acknowledged Zuccarelli's talent and popularity. Zuccarelli's inclusion underscored the high regard in which he was held and the significant role Italian artists played in the London art scene. His presence in London not only brought him personal success but also exposed British artists and collectors directly to his charming Rococo landscape style.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

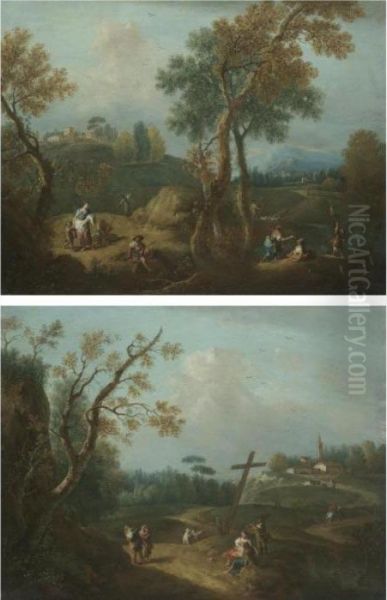

Francesco Zuccarelli's artistic signature lies in his mastery of the pastoral landscape, a genre deeply rooted in the classical tradition but infused with the lighter, more decorative spirit of the Rococo. His paintings typically depict idealized rural scenes, evoking the mythical Arcadia – a harmonious realm where humankind lives in gentle accord with a benevolent nature. These are not rugged, untamed wildernesses, nor are they specific, topographically accurate locations. Instead, they are carefully composed visions of tranquility, designed to charm and delight the viewer.

The influence of Claude Lorrain is undeniable, particularly in the handling of light and atmospheric perspective. Zuccarelli often employed a soft, diffused light, creating a serene and slightly hazy ambiance. Like Lorrain, he structured his landscapes with receding planes, often using framing elements like picturesque trees or gentle hills to lead the eye into the composition. Water, in the form of meandering rivers, tranquil pools, or small cascades, is a frequent motif, adding movement and reflecting the soft light of the sky. Architectural elements, such as rustic bridges, distant villas, or occasionally classical ruins, add points of interest and contribute to the idyllic mood.

However, Zuccarelli adapted the Claudian model to suit the tastes of his own time. His colour palette is generally lighter and brighter than Lorrain's, featuring delicate blues, fresh greens, soft pinks, and warm yellows, characteristic of the Rococo aesthetic. His brushwork is often fluid and feathery, especially in the rendering of foliage, contributing to the overall sense of lightness and elegance. While Lorrain's figures are often small and subordinate to the grandeur of nature, Zuccarelli's figures, or 'staffage', play a more prominent role. They are typically elegant peasants, shepherds, shepherdesses, or fisherfolk, depicted in relaxed poses, engaged in simple rural activities or leisurely conversation. Their costumes are often idealized and colourful, adding decorative accents to the scene. Occasionally, he incorporated mythological or biblical narratives into his landscapes, but the pastoral theme remained dominant.

His style contrasts with the more dramatic or sublime landscapes favoured by artists like Salvator Rosa or Alessandro Magnasco, and also differs from the precise topographical approach of the veduta painters like Canaletto. Zuccarelli's focus was on creating an atmosphere of gentle charm, elegance, and poetic sentiment. An interesting personal touch sometimes found in his work is the inclusion of a small pumpkin ('zucca' in Italian), a playful visual pun on his surname. While highly popular during his lifetime, this very decorative quality led to criticism in later periods when tastes shifted towards greater naturalism and emotional intensity. Nevertheless, within the context of 18th-century aesthetics, Zuccarelli's style represents a perfect fusion of classical landscape principles with Rococo grace.

Representative Works and Versatility

Francesco Zuccarelli's prolific output includes numerous landscapes that exemplify his characteristic style, many of which are now housed in major public and private collections worldwide. While specific titles can vary or refer to similar compositions, certain works stand out as representative of his achievement.

Pastoral Landscapes: Many works simply titled Landscape with Figures, Pastoral Scene, or similar variations capture the essence of his art. For instance, Landscape with Figures and Flocks showcases his typical arrangement of rolling hills, feathery trees, a gentle stream, and elegantly posed peasants tending their animals. A Wooded River Landscape with Milkmaids (found in various versions) similarly presents an idyllic scene bathed in soft light, focusing on the harmony between the figures and their serene natural surroundings. Paesaggio con contadine (Rural Landscape with Peasant Women) is another fine example from his mature period, demonstrating his skill in composition and delicate colouration.

Literary and Historical Themes: Zuccarelli occasionally ventured beyond pure pastoralism to depict literary or historical subjects within a landscape setting. His painting Macbeth meeting the witches, likely commissioned during his time in Britain, translates Shakespeare's dramatic scene into his elegant, slightly theatrical style. While the subject matter is darker than his usual fare, the treatment retains a certain Rococo grace, placing the figures within a characteristically atmospheric landscape.

Religious Subjects: Although primarily known for landscapes, Zuccarelli also produced religious works, often integrating sacred figures into pastoral settings. The Madonna and Child with St John and Angels, for example, places the holy figures within a gentle landscape, imbuing the scene with warmth and tenderness through his characteristic soft colours and idyllic atmosphere. Another known religious work is Jesus in Tyre and Sidon. These works demonstrate his versatility and ability to adapt his landscape skills to different thematic demands.

Mythological Scenes: Classical mythology also provided subjects, fitting naturally with the Arcadian mood of his landscapes. The Birth of Achilles, an early work exhibited at the Venice Academy, likely depicted the infant hero within a landscape populated by mythological figures, showcasing his engagement with classical themes from the outset of his Venetian career.

Beyond finished oil paintings, Zuccarelli was also a skilled draughtsman, producing numerous preparatory sketches and drawings that reveal his working process. Furthermore, his designs were used for tapestries, extending his influence into the decorative arts. The sheer number and consistent quality of his works attest to his skill, popularity, and industrious nature throughout his long career. His paintings can be found today in collections such as the Royal Collection Trust (UK), the National Gallery (London), the Wallace Collection (London), the Gallerie dell'Accademia (Venice), the Uffizi Gallery (Florence), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), among many others.

Collaborations, Engravings, and Wider Influence

Francesco Zuccarelli's impact extended beyond his individual paintings through collaborations, the dissemination of his work via engravings, and his influence on contemporary taste, particularly in Britain. Collaboration was a common feature of the 18th-century art world, allowing artists to combine their specialist skills efficiently. As mentioned, Zuccarelli worked with Antonio Visentini in Venice, likely combining Visentini's architectural expertise with his own landscape and figure painting. He also associated with Bernardo Bellotto, suggesting a collegial atmosphere among leading Venetian painters catering to an international clientele.

Perhaps even more significant for the spread of his reputation was the reproduction of his paintings as engravings. This practice allowed images to circulate far more widely than unique paintings could. Zuccarelli collaborated notably with the Swiss engraver Francis Vivares, who settled in London and became one of the foremost reproductive engravers of landscape paintings. Vivares translated many of Zuccarelli's popular compositions into prints, making his idyllic style accessible to a broader audience in Britain and beyond. These engravings not only popularized Zuccarelli's name but also served as models and inspiration for other artists and designers.

In Britain, Zuccarelli's success was part of a broader fascination with Italian landscape painting. His style, alongside the works of Claude Lorrain (already highly esteemed) and contemporaries like Canaletto and Marco Ricci (another influential Venetian landscape painter who worked in England earlier in the century), shaped the aesthetic preferences of British collectors. His influence can be seen in the context of early British landscape painters. Richard Wilson, often called the "father of British landscape painting," shared Zuccarelli's admiration for Claude Lorrain and also spent time in Italy. While Wilson developed a more robust and classical style, the prevailing taste for Arcadian scenes, partly fostered by Zuccarelli's popularity, formed the backdrop against which he worked. Even Thomas Gainsborough, whose landscapes moved towards a more personal and naturalistic style, showed an awareness of the Rococo elegance present in Zuccarelli's work in his earlier landscapes.

Zuccarelli's role as a founding member of the Royal Academy further cemented his position within the British art establishment. He participated in its early exhibitions, contributing to the dialogue and development of art in London. His long stays in the city ensured direct interaction with British artists, patrons, and the viewing public, leaving a tangible mark on the artistic landscape of 18th-century Britain. His work represented a specific type of idealized landscape that remained popular for decades, serving as both a benchmark and a point of departure for subsequent generations. Other Italian artists popular in London at the time, such as the portraitist Pompeo Batoni (though based in Rome), were part of the same cultural exchange that Zuccarelli exemplified.

Later Years, Legacy, and Reassessment

After his second successful period in London, Francesco Zuccarelli eventually returned to Italy. He spent time in Venice, where his reputation remained high. In 1772, his standing within the Venetian art community was formally recognized when he was elected President of the Venetian Academy of Painting and Sculpture. This prestigious position confirmed his status as one of the leading figures in the city's artistic life, following in the footsteps of masters like Tiepolo. He continued to paint, though perhaps less prolifically than during his peak years.

His final years were spent in Florence, the city where he had received part of his early training. He died there in 1788, at the advanced age of 86, concluding a long and remarkably successful international career. By the time of his death, artistic tastes were already beginning to shift. The elegance and artifice of the Rococo were gradually giving way to the sterner virtues of Neoclassicism, inspired by archaeological discoveries and revolutionary ideals, and the burgeoning sensibility of Romanticism, which emphasized emotion, individualism, and the sublime power of nature.

Consequently, during the 19th century, Zuccarelli's reputation experienced a decline. The rise of Naturalism in landscape painting, championed by artists like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner in Britain and the Barbizon School in France, placed a premium on direct observation of nature and a more emotionally charged or scientifically accurate depiction of the world. Compared to these trends, Zuccarelli's idealized, decorative pastorals could seem superficial or formulaic to later critics. His work was sometimes dismissed as overly sweet or lacking in substance.

However, the 20th and 21st centuries have witnessed a significant reassessment of Zuccarelli's art and historical importance. Art historians, particularly Italian scholars, have revisited his work, appreciating its technical skill, decorative charm, and historical significance within the context of 18th-century European culture. Exhibitions and publications have shed new light on his career, acknowledging his role as a key exponent of the Rococo landscape, his importance in the artistic exchange between Italy and Britain, and his influence on collecting tastes. Today, his paintings are admired for their elegance, their technical finesse, and their embodiment of the Arcadian ideal that held such appeal for his contemporaries. He is recognized not as a revolutionary innovator, but as a consummate master of a particular style, whose work brought pleasure to many and left a distinct mark on the history of landscape painting.

Conclusion: An Enduring Charm

Francesco Zuccarelli navigated the complex art world of the 18th century with remarkable success, establishing himself as a leading landscape painter first in Italy and then, significantly, in Great Britain. His art, characterized by idyllic pastoral scenes, soft light, delicate colours, and elegant figures, perfectly captured the Rococo spirit of grace and charm. Deeply influenced by the classical tradition of Claude Lorrain, he adapted this heritage to create a distinctive style that resonated with the tastes of an international clientele, particularly the British aristocracy engaged in the Grand Tour.

His collaborations with artists like Antonio Visentini, his connections with influential patrons like Consul Joseph Smith and King George III, and his role as a founding member of London's Royal Academy highlight his integration into the highest levels of the European art scene. The widespread dissemination of his work through engravings by figures like Francis Vivares further amplified his influence. While his reputation waned with the rise of Romanticism and Naturalism, modern scholarship has rightfully restored his position as a significant figure in 18th-century art history. Zuccarelli's enduring legacy lies in his mastery of the pastoral landscape, his contribution to Anglo-Italian cultural exchange, and the sheer visual delight that his charming Arcadian visions continue to provide. His work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of idealized beauty and the sophisticated artistry of the Rococo era.