Introduction: A Belgian Heart in Spanish Art

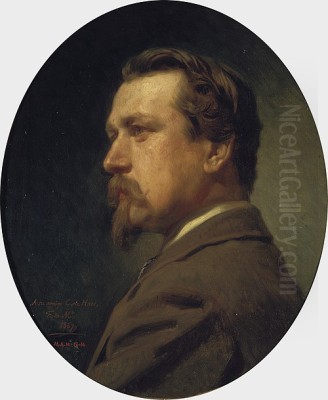

Carlos de Haes stands as a pivotal figure in the history of 19th-century Spanish art. Born in Brussels, Belgium, on January 25, 1826, he would later become a naturalized Spanish citizen and revolutionize the genre of landscape painting within his adopted country. His death occurred in Madrid, Spain, on June 18, 1898, concluding a career that firmly established Realism as a dominant force in Spanish landscape art, moving away from the prevailing Romantic traditions. De Haes was not just a painter but also an influential educator whose methods and vision shaped a generation of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation: From Brussels to Málaga and Back

Carlos de Haes's journey into the art world began under somewhat challenging circumstances. His family, facing financial difficulties, relocated from Brussels to the southern Spanish city of Málaga. It was here, around 1835, that the young Haes commenced his formal artistic training. His first significant mentor was Luis de la Cruz y Ríos, a notable portraitist who had served as a court painter. This initial instruction in Málaga provided Haes with a foundational understanding of drawing and painting techniques within the Spanish artistic environment.

Seeking further refinement and exposure to different artistic currents, Haes returned to his native Belgium around 1850. This period proved crucial for his development as a landscape painter. He immersed himself in the study of the Flemish and Dutch landscape traditions, known for their meticulous observation and realistic portrayal of nature. A key influence during this time was the Belgian landscape painter Joseph Quinaux. Working alongside Quinaux, Haes honed his skills, particularly embracing the practice of painting outdoors (plein air), directly capturing the nuances of light, atmosphere, and natural forms. This Belgian interlude solidified his commitment to Realism and equipped him with the technical and philosophical tools that would define his later career in Spain.

The Rise of a Realist Vision in Spain

Upon returning to Spain in the mid-1850s, Carlos de Haes settled in Madrid, the vibrant heart of the country's art scene. He brought with him a fresh perspective on landscape painting, one deeply rooted in the principles of Realism and direct observation, which contrasted sharply with the more idealized and often historically or mythologically themed landscapes popular in Spain at the time, often associated with Romanticism. Haes championed the idea that nature itself was a worthy subject, devoid of narrative pretext.

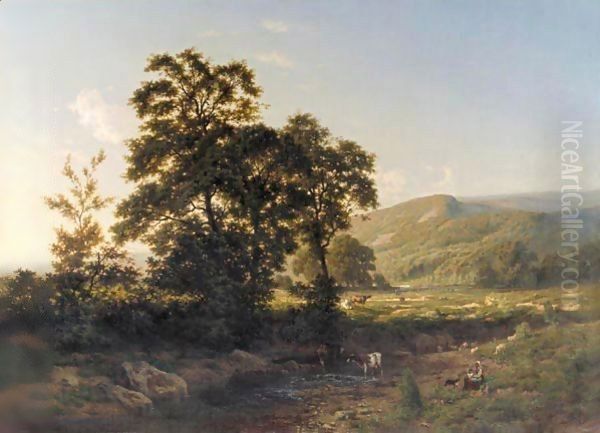

His artistic style was characterized by a profound commitment to capturing the objective reality of the landscapes he encountered. He meticulously studied and rendered the specific textures of rocks, the intricate forms of trees, the changing conditions of the sky, and the play of light across different surfaces. His approach was influenced by both the detailed precision associated with Neoclassicism and the burgeoning Realist movement sweeping across Europe. He believed in immersing himself in the environment, undertaking numerous sketching trips across Spain and other parts of Europe to gather material directly from nature.

De Haes's works often featured grand, panoramic compositions, yet they retained a sense of intimacy through their detailed execution. He employed large canvases, which allowed for a monumental depiction of nature, emphasizing its scale and power. His focus on luminosity, accurate proportions, and the tangible qualities of the natural world marked a significant departure. This dedication to direct observation and realistic representation was pioneering within the context of mid-19th-century Spanish landscape painting, setting a new standard for the genre.

A Revolutionary Educator: The Chair of Landscape Painting

Carlos de Haes's impact extended far beyond his own canvases. In 1857, a significant milestone occurred when he won the first-ever professorship dedicated exclusively to landscape painting at the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. This appointment was revolutionary, formally recognizing landscape painting as a major academic discipline in Spain, distinct from historical or figure painting.

As a professor, Haes implemented teaching methods that were as innovative as his art. He strongly advocated for students to abandon the confines of the studio and the reliance on copying established masters or working purely from imagination, which were common practices inherited from Romantic and academic traditions. Instead, he urged his students to engage directly with nature, encouraging extensive outdoor sketching and painting (plein air) expeditions. He believed that only through direct, empirical observation could an artist truly understand and faithfully represent the complexities of the natural world.

His pedagogical approach emphasized capturing the truth of the landscape – its specific light, atmosphere, and geological or botanical details. This focus on realism and experiential learning profoundly influenced his students. He nurtured a new generation of Spanish painters who embraced landscape painting with renewed vigor and a modern perspective. His tenure at the Academy lasted for decades, cementing his legacy as a transformative figure in Spanish art education.

Shaping the Next Generation: Students and Contemporaries

The influence of Carlos de Haes as a teacher was immense, shaping the careers of many artists who would become leading figures in Spanish art. Perhaps his most celebrated pupil was Aureliano de Beruete, who became a master landscape painter in his own right, known for his depictions of the Castilian landscape and his embrace of Impressionist techniques later in his career, while still retaining the foundational realism learned from Haes.

Other notable students who benefited from Haes's guidance included Darío de Regoyos, who would later explore Post-Impressionism and become a unique voice in Spanish painting, and Damián de la Reina. These artists, though developing their own distinct styles, carried forward the emphasis on direct observation and the importance of landscape as a primary subject that they had learned under Haes.

Within the broader context of 19th-century Spanish art, Haes's work can be seen in dialogue with other important figures. While he represented a move away from the Romantic landscapes of artists like Jenaro Pérez Villaamil, who often depicted picturesque ruins and dramatic historical settings, Haes built upon the growing interest in national landscapes. His contemporaries and students formed a crucial link in the evolution of Spanish painting, paving the way for later movements like Impressionism and Symbolism to take root in Spain. The artists directly influenced by Haes, including Aureliano de Beruete, Darío de Regoyos, and Damián de la Reina, along with his own teachers Luis de la Cruz y Ríos and Joseph Quinaux, and contemporary Jenaro Pérez Villaamil, represent a significant network within the artistic landscape of the time.

Masterworks and Artistic Signatures

Carlos de Haes produced a substantial body of work throughout his career, much of which is now housed in major Spanish institutions, particularly the Prado Museum in Madrid. His paintings are celebrated for their technical skill, compositional strength, and faithful representation of diverse natural environments.

Among his most renowned masterpieces is The Mancorbo Canal in the Picos de Europa (also referred to as The Pancorbo Canal in Europe's Mountains), painted in 1876. This large-scale work is often considered the pinnacle of his career, showcasing his ability to capture the rugged grandeur of the Spanish mountains with remarkable detail and atmospheric sensitivity. It exemplifies his mature style, balancing monumental scale with meticulous attention to geological formations and light effects. This painting received significant acclaim, including praise at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in the United States in the same year, highlighting his international recognition.

Another significant early work is Forest and River (1857), which demonstrates his commitment to realism shortly after his appointment at the Academy. Other notable titles mentioned in various sources include Mountain Landscape, Suburbs of Madrid, Reminiscences of the Pyrenees, Mountain Landscape with Torrent (Paisaje montañoso con torrente), and Mountains of Asturias (1875). These works collectively showcase his thematic range, from the high peaks of the Pyrenees and Picos de Europa to more pastoral scenes and the outskirts of the capital.

A key aspect of Haes's artistic practice was his prolific creation of small oil sketches, often referred to as apuntes or estudios. These were typically painted on cardboard or small panels during his travels throughout Spain, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. These sketches served as direct records of his observations – capturing fleeting effects of light, specific cloud formations, the texture of rocks, or the character of vegetation. While sometimes used as studies for larger studio paintings, many of these sketches are now valued as artworks in their own right, admired for their freshness, spontaneity, and intimate connection to the natural world. They reveal his working process and his relentless pursuit of capturing nature's truth.

His technical approach often involved a combination of precise drawing, careful layering of paint, and varied brushwork. He was adept at using thin, transparent washes (glazes) to render atmospheric effects like mist or distant haze, particularly in skies and water. Conversely, he could employ thicker, more textured brushstrokes (impasto) to convey the solidity and roughness of rock formations or the density of foliage. This technical versatility allowed him to achieve a high degree of realism and tactile quality in his depictions.

Recognition, Criticism, and Artistic Debates

Carlos de Haes achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. His participation in Spain's National Exhibitions of Fine Arts was marked by success. He gained significant notice at his first major showing in 1856. In 1857, he was awarded a third-class medal, further establishing his reputation. His works, particularly the large-scale landscapes submitted to these official salons, were often well-received and acquired for state collections, contributing to his professional standing and influence. The aforementioned success of The Mancorbo Canal in 1876, both in Spain and internationally in Philadelphia, marked a high point in his public acclaim.

However, his career was not without critical debate. Some contemporary critics, while acknowledging his skill, pointed to perceived limitations in his work. One recurring criticism suggested that his themes became somewhat repetitive over time, focusing heavily on specific types of landscapes, particularly mountainous or rugged terrains. Linked to this was the critique that his technical approach did not evolve significantly throughout his long career, which some viewed as a lack of artistic development.

Another line of criticism, perhaps paradoxically, accused him of occasionally beautifying nature too much, sacrificing a degree of raw authenticity for picturesque effect. This suggests a tension perceived by some viewers between his stated aim of objective realism and the final aesthetic choices made in his paintings. These critiques highlight the ongoing debates within the 19th-century art world about the nature of realism, the role of the artist's interpretation, and the balance between objective observation and aesthetic composition.

Despite these critical voices, Haes's position remained secure, largely due to his undeniable technical mastery, his foundational role in establishing modern landscape painting in Spain, and his powerful institutional influence through his professorship at the San Fernando Academy. The sources consulted indicate that while his art sparked discussion and occasional dissent, there were no major personal scandals or specific controversial events that significantly marred his professional trajectory. His success was built on solid artistic achievement and significant contributions to the field.

Legacy: The Father of Modern Spanish Landscape

The legacy of Carlos de Haes in Spanish art history is profound and enduring. He is widely regarded as one of the founding fathers of modern Spanish landscape painting. His primary contribution was steering the genre away from the subjective, often dramatic, interpretations of Romanticism towards a more objective, observational approach grounded in Realism. He instilled the belief that landscape, studied directly and truthfully, was a subject of inherent artistic value.

His role as an educator was equally significant. By establishing the first chair of landscape painting and promoting plein air methods, he fundamentally changed how landscape was taught and perceived within the Spanish academic system. He equipped a generation of artists with the tools and mindset to explore the diverse Spanish geography with fresh eyes, leading to a flourishing of landscape painting in the latter part of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The artists he trained, like Aureliano de Beruete and Darío de Regoyos, would further develop Spanish landscape painting, incorporating influences from Impressionism and other modern movements, but always acknowledging the foundational importance of Haes's realist principles.

His extensive body of work, particularly the numerous paintings and sketches now held by the Prado Museum and other collections, serves as a testament to his dedication and skill. His depictions of the Spanish landscape, from the rugged Picos de Europa to the environs of Madrid, have become iconic representations of the nation's natural heritage. He demonstrated that realistic landscape painting could be both technically rigorous and deeply expressive, capturing not just the appearance but also the atmosphere and character of a place.

Conclusion: An Enduring Influence

Carlos de Haes occupies an essential place in the narrative of Spanish art. A Belgian by birth, he became a central figure in the Spanish art world, driving the transition towards Realism in landscape painting. Through his own meticulous and evocative canvases, and perhaps even more importantly, through his decades of influential teaching at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, he reshaped the genre. He championed direct observation, plein air practice, and the inherent dignity of the natural world as an artistic subject. While subject to the critical debates of his time, his technical skill, pioneering vision, and lasting impact on subsequent generations of artists solidify his status as a master of 19th-century Spanish painting and a key architect of modern landscape art in Spain. His work continues to be studied and admired for its faithful yet sensitive portrayal of nature.