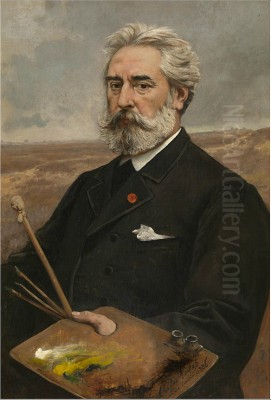

Jean Pierre François Lamorinière stands as a significant figure in the annals of 19th-century Belgian art. Born in Antwerp on April 20, 1828, and passing away in the same city on March 3, 1911, Lamorinière carved a distinct niche for himself as a landscape painter and etcher. His career unfolded during a pivotal period of artistic transition, and his work elegantly bridges the gap between the waning ideals of Romanticism and the burgeoning principles of Realism. He is celebrated for his meticulous, almost photographic, depictions of nature, particularly the sylvan landscapes of his native Belgium, rendered with a profound understanding of botanical detail and a subtle, yet palpable, poetic sensibility.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Jean Pierre François Lamorinière, often referred to as Jean-François or simply François Lamorinière, was immersed in the rich artistic environment of Antwerp from a young age. His formal artistic training commenced at the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. Here, he studied under the tutelage of respected artists, most notably Jacob Jacobs, a painter known for his seascapes and Orientalist scenes, but also a capable landscape artist. Another influential figure during his formative years at the Academy was Emmanuel Noterman, primarily a painter of genre scenes often featuring animals, whose attention to detail might have resonated with Lamorinière's own inclinations.

The Antwerp Academy, at that time, was a crucible of artistic thought, still echoing with the grandeur of Flemish Old Masters like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, yet increasingly open to contemporary European currents. Lamorinière absorbed these influences, developing a technical proficiency that would become a hallmark of his style. His early works already demonstrated a keen eye for observation and a dedication to capturing the precise character of the natural world, setting him apart from the more overtly dramatic or idealized approaches of many Romantic painters.

The Artistic Climate: Romanticism's Twilight and Realism's Dawn

To fully appreciate Lamorinière's contribution, one must understand the artistic landscape of mid-19th century Belgium. Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion, individualism, and the sublime power of nature, had been a dominant force. Painters like Gustaf Wappers, a leading figure of Belgian Romanticism, often depicted historical or dramatic scenes with great fervour. In landscape, Romantic painters sought out the picturesque and the awe-inspiring, sometimes imbuing their scenes with a sense of melancholy or grandeur.

However, by the mid-century, a new artistic movement, Realism, was gaining traction across Europe, particularly in France. Realism championed the depiction of ordinary subjects and situations with truth and accuracy, shunning artificiality and artistic conventions. In landscape painting, this translated into a desire to represent nature as it truly appeared, without idealization or overt emotionalism. The French Barbizon School, with artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny, were pioneers in this regard, advocating for direct observation and plein air (outdoor) painting.

Lamorinière emerged in this transitional period. While his meticulous detail and sometimes serene, ordered compositions could be seen as aligning with Realist principles, his profound love for nature and the often tranquil, almost spiritual quality of his forest scenes retained a subtle Romantic sensibility. He was not a stark Realist in the vein of Gustave Courbet, nor a purely Romantic painter. Instead, he forged a unique path.

Lamorinière's Distinctive Style: Precision and Poetry

Lamorinière’s style is characterized by an extraordinary attention to detail. He possessed an almost scientific understanding of botany, rendering trees, foliage, and forest undergrowth with remarkable accuracy. Each leaf, branch, and patch of moss seems to be individually observed and painstakingly recorded. This precision extended to his depiction of light and atmosphere, capturing the subtle interplay of sunlight filtering through dense canopies or the cool, damp air of a forest interior.

A key aspect of his approach was what some critics have termed "improved nature." While he based his paintings on direct and meticulous observation, he would often compose his scenes in the studio, subtly arranging elements to achieve a harmonious and aesthetically pleasing composition. This was not an idealization in the Romantic sense of adding dramatic elements, but rather a careful ordering of reality to enhance its inherent beauty and tranquility. His landscapes are often calm, static, and imbued with a sense of timelessness.

Trees were a recurring and central motif in Lamorinière's oeuvre. He depicted them not merely as landscape elements but almost as individual portraits, capturing their unique character, bark texture, and branching patterns. His forest interiors are immersive, drawing the viewer into a world of quiet contemplation. The smooth, polished finish of his paintings, with almost invisible brushstrokes, further enhances their realistic appearance, giving them a clarity that was highly admired.

Influences Shaping His Vision

Lamorinière's artistic development was shaped by a confluence of influences. The legacy of the 17th-century Dutch and Flemish Golden Age landscape painters, such as Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema, was profound. These masters were renowned for their detailed and atmospheric depictions of the Low Countries' landscapes, and their influence can be seen in Lamorinière's structured compositions and his love for woodland scenes. The meticulous rendering of foliage by artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder also finds an echo in Lamorinière's work.

The contemporary Barbizon School in France also exerted a significant influence. While Lamorinière did not adopt their often looser, more painterly plein air techniques, he shared their commitment to the faithful representation of nature. The work of Théodore Rousseau, with his detailed studies of trees and forest interiors, and perhaps the more poetic landscapes of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, would have resonated with Lamorinière's own artistic pursuits. Other Barbizon painters like Jules Dupré, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, and Constant Troyon also contributed to this broader movement towards naturalism.

In Belgium itself, he was part of a generation of landscape painters moving towards greater realism. Artists like Théodore Fourmois were also exploring a more direct and unembellished approach to landscape. Joseph Lies, a contemporary from Antwerp known for his historical genre scenes but also for his landscapes, was another artist whose work, particularly his depiction of trees and use of sombre tones, shows parallels with Lamorinière. Lamorinière, in turn, became an influential figure for younger artists who admired his technical skill and dedication to realism.

Masterpieces and Signature Themes

Among Lamorinière's most celebrated works are his depictions of the Kempen (Campine) region of Belgium, an area of heathland and pine forests. "The Fir Wood at Putte" (often simply "Pine Forest, Putte" or similar variations, with examples existing from different periods, e.g., c. 1883) is a quintessential example of his style. In such works, the towering pines are rendered with incredible precision, their needles and bark meticulously detailed. The play of light filtering through the dense canopy creates a serene, almost reverential atmosphere. The verticality of the trees often dominates the composition, leading the viewer's eye upwards.

Another notable work, "View near Edegem" (circa 1860s-1870s), showcases his ability to capture the specific character of the Belgian countryside. His paintings often feature a path or a stream leading the eye into the composition, inviting contemplation. While human figures are rare in his major landscapes, when they do appear, as in "Fishermen with a Boat" (1872), they are typically small and subordinate to the grandeur of nature, serving to provide scale or a subtle narrative touch rather than being the primary focus.

Lamorinière also painted scenes from his travels, including views from Germany and, notably, England. He spent time in Burnham Beeches, Buckinghamshire, an ancient woodland famous for its pollarded beech trees, which provided him with subjects well-suited to his detailed style. These English landscapes, such as "In Burnham Beeches" (c. 1870s), further demonstrate his mastery in capturing the unique character of different natural environments.

Lamorinière the Etcher

Beyond his significant contributions as a painter, Jean Pierre François Lamorinière was also an accomplished etcher. Printmaking, particularly etching, experienced a revival in the 19th century, valued for its ability to capture an artist's direct touch and subtle tonal variations. Lamorinière embraced this medium, translating his meticulous observational skills and love for landscape into a different, yet equally expressive, form.

His etchings often mirrored the subjects of his paintings: serene forest interiors, studies of individual trees, and tranquil countryside views. The precise lines and controlled hatching characteristic of his etching technique allowed him to achieve a similar level of detail and atmospheric effect as in his oil paintings. He understood the specific qualities of the etched line, using it to convey texture, light, and shadow with great finesse. His work in this medium contributed to the broader appreciation of etching as an original art form in Belgium. He is known to have produced etchings for other artists as well, for instance, creating two etchings for the painter Charles Conway, demonstrating a collaborative spirit within the artistic community.

Recognition, Exhibitions, and Later Career

Lamorinière's talent did not go unnoticed during his lifetime. He exhibited regularly at the Salons in Antwerp, Brussels, and Ghent, as well as internationally in cities like Paris, London, Vienna, and Philadelphia. His works were highly sought after by collectors and earned him numerous accolades. He received medals at various international exhibitions, testament to the widespread appreciation for his unique blend of realism and poetic sensibility.

He was honored with prestigious awards, including being made a Knight, then an Officer, and eventually a Commander of the Order of Leopold, one of Belgium's highest honors. This recognition underscored his status as one of the leading landscape painters of his generation. He was also a member of several artistic societies and maintained a respected position within the Belgian art world.

Throughout his long career, Lamorinière remained remarkably consistent in his style and subject matter. While artistic trends shifted around him, with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism emerging in the later decades of the 19th century, he continued to refine his meticulous, realistic approach to landscape painting. His dedication to his craft and his unwavering vision earned him lasting respect. His son, Frans Lamorinière (1854-1909), also became a painter, following in his father's footsteps to some extent, though with his own interpretations.

Legacy and Influence

Jean Pierre François Lamorinière's legacy lies in his masterful depiction of the natural world and his role as a transitional figure in Belgian art. He successfully navigated the shift from Romanticism to Realism, creating a body of work that is both a faithful record of nature and a testament to its enduring beauty. His paintings offer a window into the serene landscapes of 19th-century Belgium, rendered with a technical brilliance that continues to impress.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent Belgian landscape painters who valued detailed observation and technical skill. While later movements would explore different modes of expression, Lamorinière's commitment to capturing the tangible reality of nature, combined with a subtle poetic undertone, secured his place in the history of art. His works are held in major museum collections in Belgium, including the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp and the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, as well as in collections internationally.

Artists like Franz Courtens, who became a leading figure in Belgian Impressionism, would have been aware of Lamorinière's meticulous realism, even as they pursued different stylistic paths. The dedication to capturing the specific light and atmosphere of the Belgian landscape, a hallmark of Lamorinière's work, remained a concern for many artists who followed. Even the Symbolist landscapes of artists like William Degouve de Nuncques, while vastly different in intent, share a certain quietude and focus on the mysteries of nature that find a distant echo in Lamorinière's contemplative scenes.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Nature

Jean Pierre François Lamorinière was more than just a skilled technician; he was an artist with a profound connection to the natural world. His paintings invite viewers to pause and appreciate the intricate beauty of a forest, the play of light on leaves, or the tranquil stillness of a woodland path. In an era of artistic upheaval and changing tastes, he remained true to his vision, creating a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically rewarding.

His meticulous realism, tempered by a subtle romantic sensibility, offered a unique perspective on landscape painting. He demonstrated that a faithful depiction of nature could also be deeply poetic and evocative. As a bridge between two major artistic movements and as a master of his craft, Jean Pierre François Lamorinière holds an esteemed and enduring place in the story of Belgian and European art, his canvases continuing to transport viewers into the serene and meticulously rendered landscapes he so dearly loved.