Introduction: An Artist of Transition

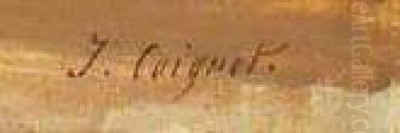

Jules-Louis-Philippe Coignet (1798-1860) stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French landscape painting. Born in Paris at the cusp of a new century, Coignet navigated the shifting artistic currents of his time, moving from the established Neoclassical tradition towards a more direct, naturalistic engagement with the landscape. As a painter, draughtsman, and lithographer, he dedicated his career to capturing the nuances of light and atmosphere, leaving behind a body of work that reflects both his rigorous training and his independent spirit of observation. His extensive travels, influential teaching, and prolific output mark him as a key transitional artist, paving the way for later movements while retaining a unique artistic identity.

Early Life and Neoclassical Foundations

Jules Coignet was born in Paris on December 2, 1798. His early life appears to have had its share of difficulties; sources suggest his mother passed away when he was young, and his relationship with his father became distant after the latter remarried. These personal circumstances may have subtly shaped his character and perhaps his dedication to his art. Professionally, his journey began firmly within the established academic system. Around 1818 to 1820, he entered the studio of Jean-Victor Bertin (1767-1842), a prominent and respected painter of Neoclassical landscapes.

Bertin was himself a student of the great theorist of Neoclassical landscape, Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750-1819). This lineage placed Coignet directly in the tradition that looked back to the idealized, structured landscapes of Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) and Claude Lorrain (1600-1682). Neoclassical landscape painting emphasized historical or mythological themes set within carefully composed, often Italianate scenery. It valued clarity, order, and a certain timeless grandeur over the specific, sometimes untidy, details of observed nature. Bertin's studio was a crucible for this style, and Coignet absorbed its lessons in composition and technique.

In 1821, Coignet's ambition led him to compete for the prestigious Prix de Rome for historical landscape painting. This competition, established to identify and support promising young artists, represented the pinnacle of academic aspiration. Although he did not win the prize, his participation signifies his early adherence to the established path and his mastery of the requisite skills. The competition itself demanded the creation of highly finished works based on specific historical or biblical subjects, reinforcing the Neoclassical emphasis on narrative and idealization within landscape.

The Turn Towards Nature: Fontainebleau and Early Works

Despite his Neoclassical training under Bertin, Coignet soon began to demonstrate an independent streak and a growing fascination with the direct observation of nature. As early as 1819, even while still formally associated with Bertin's circle, he started working in the Forest of Fontainebleau, south of Paris. This ancient woodland, with its dramatic rock formations, towering trees, and varied terrain, was becoming an increasingly popular destination for artists seeking to escape the confines of the studio and engage with nature firsthand.

His works from this period, such as Landscape in the Sandpits (1819), signal a departure from the strictures of purely historical landscape. While still composed, these paintings show a greater interest in the textures of the earth, the play of light on foliage, and the specific character of the location. Coignet began to prioritize plein air (outdoor) sketching, creating numerous studies in oil and pencil directly from nature. This practice was fundamental to his developing style, allowing him to capture fleeting effects of light and atmosphere with greater immediacy than studio-bound methods permitted.

This shift represented a move away from the theoretical constraints of Neoclassical landscape towards a more empirical, naturalistic approach. Coignet sought to record the visual truth of the landscape before him, valuing authenticity over idealized convention. While not entirely abandoning compositional structure learned from Bertin, he infused his work with a sensitivity to the specific conditions of time and place, avoiding the artificiality that could sometimes characterize purely academic landscapes. This focus on direct observation placed him among the pioneers of a new direction in French landscape art.

The Italian Journey and Early Success

Like many artists of his generation, Coignet undertook a journey to Italy, the traditional destination for completing an artistic education and absorbing the lessons of classical antiquity and the Renaissance masters. Italy, particularly the Roman Campagna and the environs of Naples, had long been the quintessential subject matter for Neoclassical landscape painters, offering picturesque ruins, dramatic coastlines, and the luminous Mediterranean light celebrated by artists like Claude Lorrain. Coignet traveled extensively through the Italian peninsula, sketching prolifically.

However, Coignet's approach to Italy differed subtly from that of his strictly Neoclassical predecessors. While he certainly depicted famous sites, his focus remained on capturing the atmospheric effects and the specific character of the Italian landscape through direct observation. His numerous sketches formed the basis for both finished paintings and a significant publishing venture. In 1825, he published Vues pittoresques de l’Italie dessinées d’après nature (Picturesque Views of Italy Drawn from Nature), a collection of sixty lithographs based on his Italian drawings. This publication showcased his skill as a draughtsman and lithographer and helped establish his reputation.

His growing prominence was confirmed in 1824 when he was awarded a Gold Medal at the prestigious Paris Salon. The Salon was the official, state-sponsored art exhibition, and success there was crucial for an artist's career. Winning a Gold Medal was a significant honour, acknowledging the quality and originality of his work and bringing him wider recognition within the Parisian art world. Works like Morning View of the Seine (1826) further demonstrated his ability to combine topographical accuracy with a poetic sensibility, capturing the specific light and mood of the Parisian landscape.

Mature Style and Official Recognition

Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, Jules Coignet solidified his artistic style and reputation. He became known for his remarkable ability to render the effects of light and atmosphere with sensitivity and precision. His landscapes often possess a delicate, almost luminous quality, achieved through careful observation and subtle tonal gradations. While rooted in naturalism, his works often convey a distinct poetic mood, avoiding mere topographical transcription. He sought the underlying character and beauty of a scene, whether it was the rugged terrain of Fontainebleau or the sun-drenched vistas of Italy.

His technical skill was matched by a growing critical and official acclaim. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Paris Salon, the primary venue for artists to display their work and gain patronage. His consistent quality and distinctive style earned him respect among critics and collectors. A major milestone in his career came in 1836 when he was awarded the Cross of the Chevalier of the Legion of Honour (Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur). This prestigious national order, established by Napoleon Bonaparte, recognized outstanding service to France, and its bestowal upon Coignet signified high official validation of his artistic achievements.

Works from this period, such as View of Chailly seen from Chailly (1834) and The Painter in a Landscape near Bozen (1837), exemplify his mature style. The former captures the expansive beauty of the Fontainebleau region with nuanced light and shadow, while the latter, set in the Tyrol region, highlights his skill in integrating figures within a convincingly rendered natural setting, emphasizing the immersive experience of painting outdoors. His panoramic view of the Fontainebleau Forest, documented around 1838, further showcases his dedication to capturing the grandeur and specific details of beloved French landscapes.

Fontainebleau and the Plein Air Ethos

Coignet's connection to the Forest of Fontainebleau remained strong throughout his career. Long before the area became synonymous with the Barbizon School, Coignet was exploring its diverse landscapes, sketching its ancient oaks, dramatic gorges, and sandy clearings. His dedication to plein air sketching was central to his artistic practice. He believed in the importance of direct contact with nature as the primary source of inspiration and information for a landscape painter. His numerous oil sketches, often executed rapidly on paper or small panels, capture the immediacy of visual experience with remarkable freshness.

This commitment placed Coignet as a precursor and contemporary to the artists who would form the core of the Barbizon School in the 1830s and 1840s. Painters like Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867), Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875), Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), and Narcisse Diaz de la Peña (1807-1876) also frequented Fontainebleau, seeking to create a more truthful and less idealized form of landscape painting. While Coignet shared their love for the forest and their emphasis on observation, his style often retained a greater degree of finish and compositional structure inherited from his Neoclassical training compared to the sometimes rougher, more atmospheric works of the core Barbizon group.

Nevertheless, Coignet played a vital role in the broader movement towards naturalism. His consistent presence in Fontainebleau and his advocacy for outdoor work contributed to the forest's status as an artistic pilgrimage site. He bridged the gap between the studio-based traditions of Bertin and Valenciennes and the more radical naturalism of Rousseau and his followers. His work demonstrated that careful observation and atmospheric sensitivity could be integrated within well-structured compositions, offering a path that was both modern and respectful of tradition.

Travels Beyond Europe: The Middle East Journey

Coignet's artistic curiosity extended beyond the familiar landscapes of France and Italy. Between 1844 and 1846, he embarked on an extensive journey to the Middle East, visiting Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon. This voyage placed him among the growing number of European artists drawn to the "Orient," fascinated by its exotic landscapes, ancient ruins, and distinct cultures. This interest, often termed Orientalism, was fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel opportunities, and a romantic fascination with lands perceived as dramatically different from Europe.

During his travels, Coignet continued his practice of sketching directly from nature, capturing the unique light, architecture, and terrain of the regions he visited. He produced numerous studies and finished works based on these travels, depicting scenes in Cairo, the Nile Valley, the Syrian desert, and the Lebanese coast. These works added a new dimension to his oeuvre, showcasing his ability to adapt his observational skills to entirely different environments. His depictions often focused on the landscape and architectural elements, rendered with his characteristic attention to atmospheric detail.

An interesting anecdote surrounds one of his Middle Eastern works. A painting titled Beirut, depicting the Lebanese coastal city, was apparently misattributed in the early 20th century to an artist named "Beyruat." It was only decades later that art historical research correctly identified the work as being by Coignet, based on his documented travels and style. This incident highlights the complexities of attribution and the potential for even established artists' works to be temporarily lost to history, while also underscoring the importance of his Middle Eastern output. His journey also connects him to other Orientalist painters like Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), and indeed his own student, Charles-Théodore Frère.

Coignet as Teacher and Theorist

Beyond his own artistic production, Jules Coignet made significant contributions as an educator and theorist of landscape painting. In 1831, he opened his own teaching studio in Paris, attracting numerous students eager to learn his methods. He was regarded as an influential and effective teacher, known for his structured approach combined with an emphasis on direct observation. His teaching philosophy aimed to equip students with both the technical skills and the perceptual awareness necessary for successful landscape painting.

Coignet formalized his teaching principles in several published works. He authored Principes et Études de paysage (Principles and Studies of Landscape Painting) and later the comprehensive Cours complet de paysage (Complete Course of Landscape Painting). These illustrated manuals provided instruction on drawing techniques, composition, and the rendering of natural elements like trees, water, and skies. They often included lithographs based on his own drawings as examples for students to study and copy, disseminating his methods far beyond his immediate pupils.

His influence as a teacher is evident in the careers of several notable artists. François-Auguste Ravier (1814-1895), known for his atmospheric landscapes often painted around Morestel, studied with Coignet. Charles-Théodore Frère (1814-1888), who became a renowned Orientalist painter, also received instruction from Coignet, likely benefiting from his master's own experiences in the Middle East. Another artist, Prosper Barbot (1798-1877), is documented as having been significantly influenced by his interactions with Coignet, leading to a shift in his own landscape style. Coignet's dedication to teaching and publishing solidified his role in shaping the next generation of landscape artists.

Lithography and the Dissemination of Views

Coignet was not only a painter but also a skilled and prolific lithographer. The early 19th century saw the rise of lithography as a popular and versatile printmaking technique, allowing for the relatively inexpensive reproduction and wide dissemination of images. Coignet embraced this medium, particularly for sharing his landscape studies and picturesque views gathered during his travels. His 1825 publication, Vues pittoresques de l’Italie, is a prime example of his work in this field.

Lithography was particularly well-suited to landscape subjects. It allowed artists to retain the fluidity and tonal variations of their original drawings, making it ideal for capturing atmospheric effects and detailed textures. Coignet's lithographs, often based on his pencil or wash drawings, demonstrate his mastery of the medium, conveying light and shadow with subtlety and precision. These prints made his interpretations of French, Italian, and later, Middle Eastern landscapes accessible to a broader public beyond those who could afford original paintings.

These publications also served an educational purpose, aligning with his role as a teacher. They provided models of landscape representation for aspiring artists and amateurs. By publishing collections of views and instructional courses illustrated with lithographs, Coignet contributed significantly to the visual culture of his time and helped popularize landscape art. His work in lithography complements his painting practice, showcasing another facet of his artistic talent and his commitment to sharing his vision of the natural world. He was mentioned alongside Camille Bernier (1823-1902) in some contexts, suggesting potential professional association, perhaps related to printmaking or Salon exhibitions, though specific collaborations are not detailed.

Artistic Style in Depth: Light, Poetry, and Realism

Analyzing Jules Coignet's artistic style reveals a sophisticated blend of inherited tradition and personal innovation. His grounding in Neoclassicism provided him with a strong sense of composition and structure, often evident in the balanced arrangement of elements within his landscapes. However, his primary distinction lies in his departure from Neoclassical idealization in favor of a more naturalistic rendering based on direct observation, particularly concerning light and atmosphere.

Coignet possessed an exceptional sensitivity to the nuances of light. Whether depicting the soft morning mist over the Seine, the clear sunlight of the Roman Campagna, or the dappled shadows within the Forest of Fontainebleau, his works capture specific lighting conditions with remarkable fidelity. This focus on transient effects aligns him with the burgeoning interest in realism and anticipates, in some respects, the later concerns of the Impressionists, though his technique remained more detailed and finished. Critics noted the "poetic" quality of his work, suggesting his ability to evoke mood and emotion through his handling of light and atmosphere, going beyond mere documentation.

His style is often described as delicate and refined. He paid close attention to detail, rendering foliage, rock formations, and architectural elements with precision, yet without sacrificing the overall unity and atmospheric coherence of the scene. This meticulousness, combined with his sensitivity to light, creates landscapes that feel both tangible and evocative. Compared to the grandeur of Poussin or the idealized calm of Claude Lorrain, Coignet offers a more intimate and specific vision of nature. While contemporaries like Corot moved towards broader, more tonal representations, Coignet often maintained a higher degree of descriptive clarity, positioning him uniquely between the structured past and the more purely optical approaches of the future.

Later Years and Legacy

Jules Coignet remained an active artist for much of his life, continuing to paint, draw, and travel. He regularly submitted works to the Paris Salon until 1857, maintaining his presence in the official art world. His later works continued to explore the landscapes he loved, particularly those of France and Italy, always marked by his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere. He passed away in Paris on April 1, 1860, at the age of 61.

In the grand narrative of French art history, Coignet occupies a position as a significant transitional figure. He successfully navigated the shift from the dominant Neoclassical landscape tradition towards the naturalism that would characterize much of 19th-century landscape painting. His early adoption and consistent practice of plein air sketching place him among the pioneers of outdoor painting in France, contributing to a movement that would eventually lead to Impressionism. His work provided a model for integrating direct observation with compositional skill.

His influence extended through his numerous students and his widely circulated publications on landscape painting. He helped shape the education of a generation of artists, instilling in them the importance of studying nature directly. While perhaps ultimately overshadowed in fame by the leading figures of the Barbizon School like Rousseau and Corot, or later by the Impressionists, Coignet's contribution remains undeniable. He was a respected artist in his own time, recognized with official honours, and his work continues to be appreciated for its technical skill, poetic sensibility, and faithful yet artistic rendering of the natural world.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Nature

Jules Coignet's career exemplifies the dynamic evolution of landscape painting in early to mid-19th-century France. Trained in the Neoclassical tradition under Jean-Victor Bertin, he embraced the growing imperative to study nature directly, becoming an early and dedicated practitioner of plein air painting, particularly in the Forest of Fontainebleau. His extensive travels throughout Europe and the Middle East provided rich material for his paintings and influential lithographic publications. Renowned for his exquisite handling of light and atmosphere, Coignet forged a distinctive style that balanced observed reality with poetic feeling. Through his art, his teaching, and his theoretical writings, he played a crucial role in bridging the gap between idealized landscape conventions and the rise of naturalism, leaving a lasting legacy as a skilled, sensitive, and influential interpreter of the natural world.