César Pattein stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born into the agricultural heartland of French Flanders, he dedicated his career primarily to depicting the lives, labours, and simple joys of the rural populace. Working within the traditions of Realism and Naturalism, Pattein captured a world undergoing profound change, often choosing to emphasize its enduring charm, familial bonds, and the innocence of childhood. Influenced by his upbringing and his association with prominent artists like Jules Breton, Pattein developed a distinctive style characterized by careful observation, a bright palette, and a gentle, optimistic portrayal of peasant life that found favour with the public and earned him recognition in the competitive Parisian art scene.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Flanders

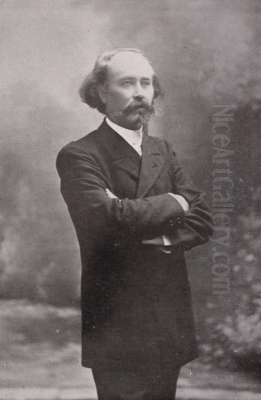

Henri Joseph César Pattein was born on September 30, 1850, in Steenvoorde, a commune in the Nord department of Northern France, close to the Belgian border. This region, French Flanders, possessed a rich cultural and artistic heritage, distinct from that of central France. Growing up in a farming family provided Pattein with an intimate, firsthand understanding of the rhythms of agricultural life, the landscape of the Nord, and the character of its inhabitants. This early immersion in the rural world would become the bedrock of his artistic subject matter throughout his long career.

His initial artistic inclinations led him towards engraving, a discipline requiring precision and attention to detail. However, his aspirations soon turned to painting. He enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Lille, the major regional art institution. There, he received a solid academic training, likely studying under figures such as Alphonse Colas (1818-1887), a respected painter and director of the school known for his portraits and historical scenes. This formal education equipped Pattein with the technical skills in drawing, composition, and colour theory necessary for a successful career within the established art system of the time.

During his early years as an artist, Pattein explored various genres then popular and encouraged by academic training. He produced portraits, demonstrating his skill in capturing likenesses, and also tackled religious and historical subjects. An early work exhibited was a Portrait of a Young Girl, shown at the Lille exhibition in 1881. While competent in these areas, it was the depiction of contemporary rural life that would ultimately define his artistic identity and become his primary focus.

The Influence of Jules Breton and Naturalism

A pivotal moment in Pattein's development came through his association with Jules Breton (1827-1906). Breton, also a native of the Nord region (born in Courrières), was one of the most celebrated painters of peasant life in the latter half of the 19th century. His work, which combined Realist observation with a certain poetic and often idealized sensibility, resonated deeply with both critics and the public. Breton was admired for his dignified portrayals of field workers, particularly women, often set against the luminous landscapes of Northern France.

Sources suggest Pattein entered Breton's circle or studio around the mid-1880s. Whether this was formal tutelage or a more informal mentorship and collaboration, the impact was profound. Pattein absorbed Breton's thematic concerns and aspects of his style. He embraced the depiction of everyday rural activities – harvests, gleaning, market days, moments of rest – and shared Breton's focus on the structure of the peasant family and the perceived virtues of agricultural labour.

This connection placed Pattein firmly within the Naturalist movement in painting. Naturalism, emerging from Realism, sought an objective, almost scientific depiction of reality, often focusing on specific social groups or environments. Painters like Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852-1929) and Léon Lhermitte (1844-1925) were prominent exponents, meticulously rendering scenes of rural and working-class life. Pattein's work aligns with this trend, though often imbued with a greater degree of sentimentality and charm than the sometimes harsher depictions by other Realists like Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), whose portrayals of peasants often carried a weightier, more monumental gravity.

The artistic milieu around Breton also included his daughter, Virginie Demont-Breton (1859-1935), herself a successful painter specializing in scenes of mothers, children, and fisherfolk. Pattein's association with this family likely reinforced his interest in themes of domesticity and childhood within the rural context.

Themes and Subject Matter: An Idyllic Countryside

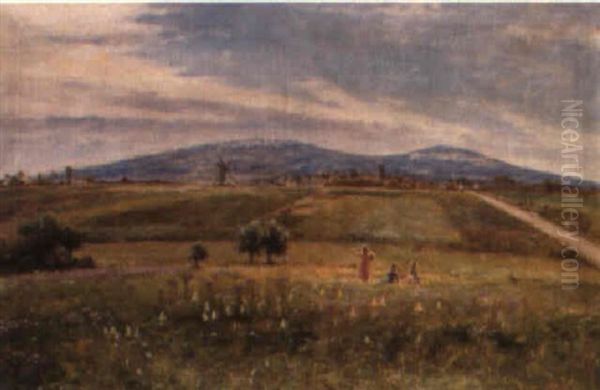

César Pattein's oeuvre is dominated by scenes of rural life, primarily set in his native French Flanders. He became a specialist in genre painting, capturing anecdotal moments and characteristic activities of the countryside. Unlike some Realists who focused on the back-breaking toil and poverty that could accompany peasant existence, Pattein generally presented a more optimistic and idealized vision. His canvases are often bathed in sunlight, populated by healthy, contented figures engaged in their daily routines.

A recurring and central theme in Pattein's work is childhood. He depicted children with particular tenderness and frequency, showing them playing games, interacting with animals, helping parents with light chores, or simply exploring the natural world around them. Works like Bulles de Savon (Soap Bubbles), exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1882, exemplify this focus on youthful innocence and simple pleasures. Un Nid d'Oiseaux (A Bird's Nest) highlights the connection between children and nature, a common trope in idyllic representations of country life.

Family interactions are another cornerstone of his subject matter. He often portrayed multiple generations together, reinforcing notions of familial harmony and the continuity of rural traditions. Scenes might depict families working together in the fields, sharing a meal, or resting at the end of the day. These images resonated with a bourgeois audience that often held nostalgic views of the countryside as a repository of traditional values, contrasting with the perceived anonymity and disruption of urban industrial life.

While idealized, his work is rooted in observation. Details of clothing, agricultural tools, domestic interiors, and the specific landscape of Northern France are rendered with care. He painted harvest scenes, depicting the communal effort involved, and market scenes capturing the social aspects of rural commerce. Works titled like Along the Road often feature figures traversing the landscape, suggesting the routines and journeys inherent in country living. Pattein effectively became a visual chronicler of the customs and appearance of his region during a period of gradual modernization.

Artistic Style and Technique

Pattein's style reflects his academic training and his alignment with Naturalism, tempered by a personal inclination towards charm and pleasantness. His technique is characterized by careful drawing and a relatively smooth finish, although perhaps not as highly polished as some strictly academic painters. He avoided the radical brushwork and colour experiments of the Impressionists like Claude Monet (1840-1926) or Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), who were his contemporaries but pursued very different artistic goals focused on capturing fleeting effects of light and modern life.

Light plays a crucial role in Pattein's paintings. He favoured clear, bright daylight, often depicting scenes under sunny skies. This contributes significantly to the cheerful and optimistic mood prevalent in much of his work. His palette is generally warm and inviting, with naturalistic colours accurately rendering landscapes, foliage, and rustic attire. He demonstrated skill in depicting textures – the roughness of homespun cloth, the smoothness of skin, the varied surfaces of the natural environment.

Compositionally, his works are typically well-structured and balanced, adhering to established conventions. Figures are clearly delineated and occupy a believable space, often arranged in narrative groupings that are easy to read. While his focus was on figures and genre scenes, the landscape settings are rendered with care, accurately reflecting the terrain of Northern France. His approach can be compared to other successful genre painters of the era, such as Julien Dupré (1851-1910), who also specialized in harvest scenes and depictions of peasant labour, often with a similar combination of realism and anecdotal appeal.

Pattein's style remained relatively consistent throughout his career. He found a successful formula that appealed to the tastes of the time and continued to refine it rather than exploring significant stylistic innovations. His strength lay in the sympathetic observation and skillful rendering of his chosen subject matter.

Career, Exhibitions, and Recognition

Like most artists seeking professional success in 19th-century France, Pattein recognized the importance of exhibiting at the official Paris Salon, organized by the Société des Artistes Français. He began submitting works regularly from 1882, starting with Bulles de Savon. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain visibility, attract patrons, and achieve critical recognition. Pattein became a consistent participant for many years.

His participation was rewarded with official honours, indicating his acceptance by the art establishment. He received a medal at the Amiens exhibition in 1885 (Silver). At the Paris Salon, he was awarded a third-class medal (Bronze) in 1896, likely for a work such as Le Peintre est Absent (The Painter is Absent), and a second-class medal (Silver) in 1906. These awards were significant achievements, confirming his status as a respected professional artist.

While participating in the Parisian art world, Pattein largely remained based in his home region. He lived and worked near Steenvoorde and Lille for most of his life, making occasional trips to Paris for exhibitions. This regional grounding likely contributed to the authenticity of his depictions of local life. He also exhibited his work in provincial cities, maintaining a connection with his local audience.

His paintings found a ready market among middle-class collectors who appreciated their accessible subject matter, technical skill, and positive portrayal of rural life. The themes of family, innocence, and honest labour held broad appeal. His association with the highly successful Jules Breton also likely enhanced his reputation and marketability. Other artists depicting rural themes, such as Émile Friant (1863-1932) or the animal painter Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), similarly catered to this public taste for realistic yet often reassuring images of the non-urban world.

Representative Works

Several works stand out as representative of Pattein's typical subjects and style:

Bulles de Savon (Soap Bubbles, 1882): Exhibited early in his Salon career, this work likely depicted children engaged in the simple pastime of blowing bubbles, showcasing his focus on childhood innocence and genre scenes.

Un Nid d'Oiseaux (A Bird's Nest): This title suggests a scene of children discovering a nest, emphasizing their connection with nature and the theme of discovery. It was notable enough to be mentioned in the publication Le Magasin Pittoresque in 1925.

Le Peintre est Absent (The Painter is Absent, 1896): Exhibited the year he won his first Paris Salon medal, this title hints at a more complex narrative or perhaps a self-referential studio scene, though still likely within a genre context.

Along the Road: Titles like this typically feature peasants, perhaps a family or workers, walking or resting along a country path, integrating figures into the landscape and depicting daily routines.

Jeune femme à la lecture (Young Woman Reading, 1883): An example of his portrait or single-figure studies, showing his ability to capture quiet, intimate moments. Auctioned in 2007.

La fille de l'artiste contre la balustrade fleurie (The Artist's Daughter against the Flowered Balustrade, 1887): This suggests a personal portrait, possibly set in a garden, combining portraiture with a pleasing natural setting. Auctioned in 2011.

These works, alongside numerous others depicting harvests, farmyards, and domestic interiors, collectively build a comprehensive picture of Pattein's artistic world – one centered on the people and landscapes of French Flanders, rendered with skill and sympathy.

Context: Rural Painting in 19th Century France

César Pattein worked during a period when the depiction of rural life was a major theme in French art. This interest stemmed from various factors: the legacy of the Barbizon School painters like Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867) and Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), who had elevated landscape painting; the rise of Realism led by Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), who championed scenes of ordinary life and labour; and a growing sense of nostalgia for the countryside amidst rapid industrialization and urbanization.

Artists approached rural themes in diverse ways. Millet imbued his peasants with a sense of timeless dignity and hardship. Courbet sometimes used rural scenes for social commentary. Breton, Pattein's mentor, found a balance between realism and poetic idealization that proved immensely popular. Others, like Léon Lhermitte, focused on the meticulous, almost photographic rendering of agricultural work. Pattein carved his niche within this context by emphasizing the lighter, more cheerful aspects of rural existence, particularly family life and childhood, presented with competent technique and appealing sentiment.

His work offered an alternative to both the starkness of some Realist depictions and the avant-garde experiments of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. For many art buyers, Pattein's paintings provided reassuring images of stability, tradition, and simple virtues, making his work commercially viable and ensuring his recognition within the Salon system.

Later Life, Legacy, and Market

César Pattein continued to paint and exhibit into the early 20th century, staying true to the style and subjects that had brought him success. He remained deeply connected to his native region throughout his life. He passed away in Hazebrouck, another town in the Nord department, not far from his birthplace, in 1931, at the age of 80.

His legacy is that of a dedicated and skilled painter of French rural life, particularly the specific culture and landscape of French Flanders. While not an innovator in the mold of the Impressionists or later modernists, he was a master of his chosen genre, creating a body of work appreciated for its technical quality, observational detail, and sympathetic portrayal of human subjects. His paintings serve as valuable visual documents of regional customs and agricultural practices at the turn of the century.

Today, Pattein's works are held in several public collections, notably in Northern France, including the Musée des Augustins in Hazebrouck. His paintings also appear regularly on the art market. Auction results, such as those mentioned for Jeune femme à la lecture (sold for €2000 in 2007) and La fille de l'artiste... (estimated €4000-€6000 in 2011), indicate a steady, if not spectacular, level of collector interest. Well-preserved examples depicting his characteristic themes of cheerful family life and children in sunny landscapes tend to be the most sought after.

Conclusion

César Pattein occupies a respected place within the tradition of French Naturalist painting. Rooted in the soil of French Flanders and guided by the example of Jules Breton, he devoted his art to celebrating the enduring qualities of rural life. His canvases, filled with sunlight, diligent farmers, happy families, and innocent children, offered a comforting and idealized vision that resonated with his contemporaries. Though overshadowed by the revolutionary movements transforming art during his lifetime, Pattein's skillful technique, consistent focus, and gentle portrayal of humanity ensure his work retains its charm and historical significance as a heartfelt chronicle of a specific time and place. He remains an important figure for understanding the diversity of artistic practice in late 19th and early 20th-century France and the enduring appeal of the pastoral ideal.