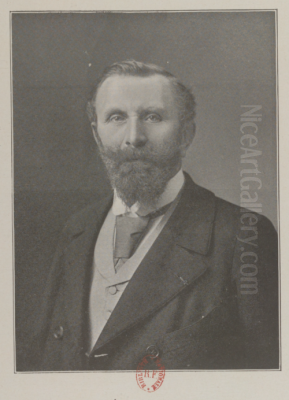

Aimé Perret stands as a significant figure in French genre painting of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in Lyon in 1847 and passing away in 1927, his life spanned a period of immense social and artistic change in France. While Impressionism revolutionized the Parisian art scene, Perret dedicated his career primarily to capturing the enduring rhythms and textures of rural life, particularly in the Bresse region near his native Lyon. He became a respected and popular artist in his time, known for his detailed, empathetic, and often picturesque depictions of peasants, farm activities, and the gentle landscapes of his chosen locale. His work offers a valuable window into a way of life that was steadily transforming under the pressures of modernity.

Perret's paintings are characterized by their careful observation, solid draftsmanship, and sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere. He was a painter grounded in the traditions of Realism and Naturalism, focusing on the tangible world and the everyday experiences of ordinary people. Unlike some of his contemporaries who might have overly romanticized or dramatized rural existence, Perret often struck a balance, portraying the dignity of labor and the simple moments of rest and community without shying away from the realities of peasant life. His legacy is that of a dedicated chronicler, preserving the visual identity of regional France through a lens of sincerity and accomplished technique.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Lyon

Aimé Jules Perret was born on March 12, 1847, in Lyon, a city with a rich artistic and cultural heritage, particularly known for its silk industry and its own distinct school of painting. Details about his early family life are not extensively documented, but it is clear that his artistic inclinations emerged early. Lyon provided a fertile ground for a budding artist, boasting institutions like the École des Beaux-Arts, which had nurtured prominent artists before him. It was here that Perret received his foundational artistic training.

At the École des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, Perret studied under respected masters who instilled in him the importance of academic principles, particularly drawing and composition. One of his significant teachers was Joseph Guichard, himself a pupil of both Ingres and Delacroix, representing a bridge between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. Guichard's influence likely encouraged Perret's commitment to strong drawing and careful composition, even as Perret later moved towards Realist subject matter. This rigorous training provided Perret with the technical skills necessary to execute his detailed observations of the world around him.

While Lyon remained his base for much of his life, Perret, like many ambitious provincial artists of his time, also looked towards Paris, the undisputed center of the French art world. He is known to have spent time in the capital and associated with artists there. Notably, he received guidance and encouragement from Antoine Vollon, a renowned still-life and genre painter associated with the Realist movement. Vollon's robust brushwork and appreciation for texture may have influenced Perret's own handling of paint, particularly in his rendering of rustic objects, fabrics, and natural elements. This exposure to the Parisian scene broadened his horizons while reinforcing his inclination towards Realist aesthetics.

The Embrace of Realism and Rural Themes

Aimé Perret firmly situated his artistic practice within the broader currents of Realism and Naturalism that gained prominence in French art from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Reacting against the perceived artificiality of Academic history painting and the emotional excesses of Romanticism, Realists sought to depict the world as it was, focusing on contemporary life and often highlighting the experiences of the working classes. Perret embraced this ethos, turning his attention away from mythological or historical subjects towards the everyday lives of the people he knew best: the peasants and inhabitants of rural France.

His chosen subject matter aligned him with artists like Jean-François Millet, who famously depicted the hardships and dignity of peasant labor in Barbizon. While Perret's work shares thematic similarities with Millet's, it often possesses a slightly less somber and perhaps more picturesque quality. Perret seemed particularly drawn to the daily routines, communal activities, and specific character of the Bresse region. His paintings frequently feature scenes of farming, market days, domestic interiors, and quiet moments of contemplation within a rural setting. He rendered these scenes with meticulous attention to detail, capturing the textures of clothing, the specifics of agricultural tools, and the play of light on landscapes and figures.

Perret's commitment to Realism extended to his working methods. While he likely completed larger compositions in his studio, his numerous studies and the fresh, naturalistic feel of many of his works suggest an engagement with plein air (outdoor) painting, a practice strongly associated with the Barbizon School and later the Impressionists. This allowed him to capture the specific light conditions and atmospheric effects of the countryside, lending authenticity to his scenes. His figures, while carefully drawn, feel integrated into their environment, part of the natural cycle of rural life he sought to document. His approach was less about social commentary than about faithful representation, imbued with a sense of empathy for his subjects.

The Bresse Region: A Lifelong Muse

While Perret depicted various rural settings, the Bresse region held a special significance for him and became a recurring subject throughout his career. Located to the east of Lyon, stretching across parts of the Ain, Saône-et-Loire, and Jura departments, Bresse is a distinct geographical and cultural area known for its traditional timber-framed farms, fertile plains, woodlands, and perhaps most famously, its poultry. Perret found in Bresse an inexhaustible source of inspiration, a microcosm of the French rural life he wished to portray.

His paintings often capture the specific architecture of the region, such as the characteristic fermes bressanes with their tall chimneys and half-timbered walls. He depicted the local people in their traditional attire, engaged in activities typical of the area: tending livestock (especially chickens and geese), working in the fields, gathering at local markets, or participating in village festivities. Works like Marché aux Volailles à Bourg-en-Bresse (Market for Poultry at Bourg-en-Bresse) directly reference the region's identity. He seemed fascinated by the interplay between the people and their specific environment, showing how the landscape shaped their lives and customs.

Perret's connection to Bresse appears to have been deep and personal. He spent considerable time there, observing its changing seasons, its light, and its inhabitants. This familiarity allowed him to imbue his paintings with a sense of authenticity and intimacy. He wasn't merely an outsider documenting an exotic locale; he was painting a world he understood. The recurring presence of Bresse landscapes and figures in his oeuvre suggests it was more than just a convenient subject; it was a place that resonated with his artistic sensibilities and his desire to capture the enduring spirit of traditional French provincial life before it faded completely.

Subjects and Themes: The Fabric of Rural Existence

Aimé Perret's body of work explores a consistent range of subjects and themes centered on the lives of rural French people, particularly women and children, within their environment. His focus was less on grand historical narratives and more on the quiet dignity and cyclical nature of everyday existence in the countryside.

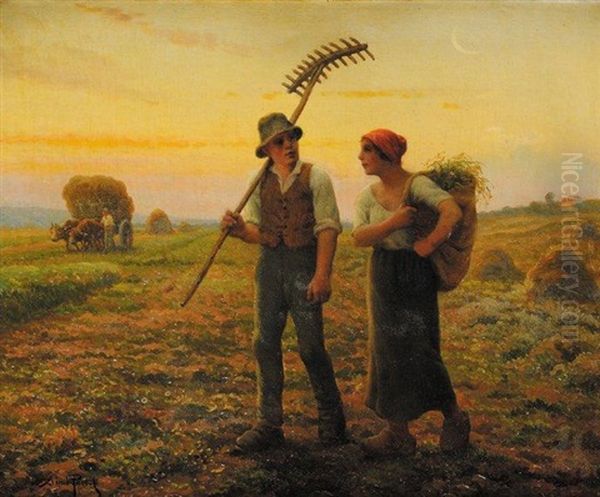

Peasant Labor: A significant portion of his work depicts men and women engaged in agricultural tasks. This includes scenes of ploughing, sowing, harvesting (Le Repas des Moissonneurs - The Meal of the Harvesters), tending animals (La Gardeuse d'Oies - The Goose Girl), and gathering produce. He portrayed labor not necessarily as heroic or brutal, but as an integral part of life, often showing moments of rest or communal effort alongside the toil.

Domestic Life: Perret frequently painted scenes set within rustic interiors or just outside farmhouses. These often feature women engaged in domestic chores like sewing, cooking, fetching water (Jeune femme au puits - Young Woman at the Well), or caring for children. These works emphasize the central role of women in maintaining the rural household and community. The interiors are often rendered with attention to detail, showing simple furniture, cooking implements, and the play of light entering through windows or doorways.

Children: Children are frequent subjects in Perret's paintings, often shown playing, assisting with simple tasks, or quietly observing the adults. His depictions of children are typically tender and unsentimental, capturing their natural curiosity and innocence within the context of their rural upbringing. They represent the continuity of life and tradition within the community.

Markets and Social Gatherings: Market scenes provided Perret with opportunities to depict the livelier, communal aspects of rural life. These paintings often feature bustling crowds, interactions between vendors and customers, and displays of local produce or livestock, as seen in his poultry market scenes. They showcase the social fabric of the village and the economic rhythms of the countryside.

Landscapes: While figures usually dominate his compositions, the landscape is always a crucial element, providing context and atmosphere. He painted the fields, rivers (particularly the Saône), farmyards, and village outskirts of the Bresse and surrounding regions. His landscapes are typically serene and naturalistic, capturing the specific quality of light and weather, contributing significantly to the overall mood of his paintings. Through these varied subjects, Perret constructed a comprehensive portrait of the world he observed.

Notable Works: Capturing Moments in Time

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be extensive, several works stand out as representative of Aimé Perret's style and thematic concerns. These paintings showcase his technical skill, his empathy for his subjects, and his dedication to depicting French rural life.

Le Père Lathuile (Father Lathuile): This title, famously associated with a restaurant depicted by Édouard Manet, likely refers to a portrait or genre scene by Perret focusing on a specific individual, perhaps a respected elder or local figure. Such works allowed Perret to explore character through detailed physiognomy and context, grounding the individual within their community.

La Bourguignonne (The Burgundian Woman): This title suggests a focus on regional identity, portraying a woman likely identifiable by her dress or features as being from Burgundy, a region adjacent to Bresse. It highlights Perret's interest in local types and customs, capturing the specific characteristics that defined different provincial populations in France. The depiction would likely emphasize her connection to the land or traditional roles.

Marché aux Volailles (Poultry Market): Perret painted several versions of poultry markets, particularly those in Bourg-en-Bresse. These works are often lively compositions filled with figures – peasant women selling geese, chickens, and ducks, potential buyers inspecting the birds, and onlookers. They demonstrate Perret's ability to handle complex multi-figure scenes and capture the bustling atmosphere of market day, a central event in rural economic and social life. The detailed rendering of the birds themselves is often a notable feature.

Retour des Champs (Return from the Fields): Scenes depicting peasants returning home after a day's labor were common themes for Realist painters. Perret's versions likely showed figures, perhaps a family unit or group of workers, walking along a country path at dusk, carrying tools or bundles of harvested crops. These paintings often evoke a sense of weariness but also quiet satisfaction, emphasizing the connection between the workers and the land they cultivate, under the soft light of evening.

Jeune femme au puits (Young Woman at the Well): Dated around 1900, this work exemplifies his focus on female figures engaged in daily tasks. Fetching water was a fundamental chore in rural life. The painting likely portrays a young woman, perhaps pausing for a moment by the well, allowing Perret to capture a sense of quiet contemplation amidst routine. The setting of the well itself, often a communal point, adds another layer of social context. The handling of light on the figure and the stone well would be characteristic of his style.

These examples, among many others, illustrate Perret's consistent engagement with the people and landscapes of rural France, rendered with careful technique and a deep sense of place.

Recognition and Career: Success at the Salons

During his lifetime, Aimé Perret achieved considerable recognition and success, primarily through the established system of the official Salons. The Paris Salon, organized annually (or biennially) by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the most important venue for artists seeking public exposure, critical attention, and potential sales or state commissions. Acceptance into the Salon was a mark of professional validation. Perret became a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon from the 1870s onwards.

His carefully executed genre scenes and landscapes found favor with Salon juries and the public. The detailed realism, combined with often appealing subject matter depicting the perceived virtues of rural life – hard work, family, tradition – resonated with audiences, including bourgeois collectors who appreciated these seemingly stable values during a time of rapid industrialization and social change. Perret's work was seen as accomplished, sincere, and accessible.

His success was marked by official accolades. He received medals at the Paris Salon on several occasions, including a third-class medal in 1880 and a second-class medal in 1881. He also achieved Hors Concours status, meaning his work was accepted for exhibition without needing jury approval, a significant privilege. Furthermore, his contributions were recognized with the prestigious Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour) in 1894, a high mark of distinction from the French state, acknowledging his standing within the national art scene. He also exhibited successfully at the Lyon Salon, maintaining his connection to his home city. This consistent recognition solidified his reputation as a leading genre painter of his generation.

Context: Contemporaries and Influences

Aimé Perret's artistic journey unfolded within a vibrant and complex period in French art history. Understanding his work benefits from placing it in context with his influences and contemporaries, both those who shared his artistic path and those who diverged significantly.

Influences: As mentioned, the foundational influence of Realism is paramount. Gustave Courbet, with his radical commitment to depicting ordinary life and his rejection of idealized subjects, paved the way for artists like Perret, although Perret's style was generally less confrontational and more polished. The profound impact of Jean-François Millet is undeniable; Millet's elevation of the peasant figure to a subject of serious art deeply influenced a generation, including Perret, who adopted similar themes of rural labor and life, albeit often with a less overtly somber or monumental tone. The technical skill and sensitivity to light found in Dutch Golden Age painters, particularly genre scenes by artists like Pieter de Hooch or landscapes by Jacob van Ruisdael, may also have provided historical precedents appreciated by Perret. His teacher Joseph Guichard and mentor Antoine Vollon were direct personal influences.

Contemporaries in Rural Genre Painting: Perret was part of a significant group of artists specializing in rural themes. Jules Breton enjoyed immense popularity for his idealized, often poetic depictions of peasant women in the fields. Léon Lhermitte was another major figure, known for his large-scale, often Zola-esque portrayals of agricultural labor, sometimes utilizing pastel with great effect. Jules Bastien-Lepage gained fame for his highly detailed, naturalistic portraits and scenes of peasant life, characterized by a cool, objective light. Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, a friend of Bastien-Lepage, also focused on meticulous renderings of rural and religious scenes, often with a photographic clarity. The animal painter Rosa Bonheur, renowned for works like The Horse Fair, shared Perret's dedication to observing the rural world, though with a focus on animal anatomy. Constant Troyon, associated with the Barbizon school, also specialized in landscapes with animals.

Broader Context: While Perret pursued Realism, the art world around him was diverse. The Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas, were revolutionizing painting with their focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and modern urban life, using broken brushwork and brighter palettes – a stark contrast to Perret's detailed finish. Simultaneously, established Academic painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau continued to produce highly finished historical, mythological, and allegorical works that remained popular at the Salons, representing a different facet of the era's official art world. Perret navigated this landscape, adhering to a Realist path that proved successful within the Salon system, distinct from both Academic convention and Impressionist innovation.

Later Life and Legacy

Aimé Perret continued to paint and exhibit actively into the early twentieth century, remaining largely faithful to the themes and style he had developed throughout his career. He maintained his studio in Lyon and likely continued his excursions into the Bresse countryside, finding enduring inspiration in the familiar landscapes and the lives of their inhabitants. The world around him was changing rapidly – the advent of the automobile, the spread of industrialization into rural areas, and the cataclysm of World War I irrevocably altered the fabric of French society, including the traditional peasant life he had so often depicted. His later works, therefore, can be seen not just as genre scenes but as valuable historical documents of a vanishing way of life.

He passed away in Lyon in 1927 at the age of 80. By the time of his death, the artistic avant-garde had moved far beyond Realism, through Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism. Consequently, like many successful Salon painters of his generation whose work fell outside the modernist trajectory, Perret's reputation experienced a decline in the decades following his death. Critical attention shifted towards the innovators who had broken radically with tradition.

However, in recent decades, there has been a renewed appreciation for the diversity of nineteenth-century art, including the contributions of accomplished Realist and Naturalist painters like Perret. His works are held in various museum collections, notably the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (which houses art from the period), and numerous regional museums in France, particularly those in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region. His paintings also appear regularly on the art market, sought after by collectors interested in French genre painting and depictions of rural life. His legacy lies in his skillful and empathetic portrayal of the French countryside and its people during a pivotal era of transition, offering a detailed and enduring visual record executed with considerable artistry.

Conclusion: A Painter of Place and People

Aimé Perret carved a distinct and respected place for himself within the landscape of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century French art. As a dedicated practitioner of Realism and Naturalism, he turned his gaze towards the everyday realities of rural France, particularly the Bresse region that served as his constant muse. Through meticulous observation, solid technical skill honed at the École des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, and a palpable empathy for his subjects, he created a comprehensive body of work documenting peasant labor, domestic life, community gatherings, and the gentle landscapes that shaped these existences.

While his contemporaries in Paris were forging revolutionary paths with Impressionism and later movements, Perret found success and validation within the established Salon system, earning medals and the Legion of Honour. He belonged to a significant cohort of artists, including Millet, Breton, Lhermitte, and Bastien-Lepage, who believed in the artistic merit of depicting contemporary rural life with honesty and dignity. His paintings offer more than just picturesque scenes; they are valuable records of regional identity, traditional practices, and a way of life undergoing profound transformation. Though perhaps overshadowed in mainstream art history by the avant-garde, Aimé Perret remains an important figure, a chronicler whose canvases continue to speak of the enduring connection between people and place in the heart of France.