Cesare Gennari (1637-1688) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Italian Baroque art, particularly within the esteemed Bolognese School. Born in Cento, a town already distinguished in the art world by his illustrious uncle, Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, famously known as Il Guercino, Cesare's life and career were inextricably linked with this towering figure of the era. As both a nephew and a dedicated pupil, Cesare Gennari not only inherited a portion of Guercino's artistic mantle but also played a crucial role in the continuation and management of his studio and legacy. His work, while deeply influenced by his master, carved its own niche, contributing to the rich artistic tapestry of 17th-century Italy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in the Shadow of Guercino

Cesare Gennari was born into an artistic dynasty. His father was Ercole Gennari, himself a painter, and his mother was Lucia Barbieri, Guercino's sister. This familial connection to one of Italy's most celebrated artists of the time undoubtedly shaped Cesare's destiny. Growing up in Cento, he would have been immersed in an environment where art was not just a profession but a way of life. The Gennari family, including Cesare's elder brother Benedetto Gennari II (1633-1715), who also became a notable painter, were integral to Guercino's workshop, known as the "Casa Gennari."

His formal artistic training naturally took place under the direct tutelage of Guercino. This apprenticeship was more than just learning technique; it was an immersion into a specific artistic vision characterized by dramatic chiaroscuro, emotional depth, and a masterful command of composition. Guercino's style evolved throughout his career, moving from an early, more robust and tenebrist manner to a later, more classical and luminous style. Cesare would have absorbed these evolving aesthetics, providing him with a versatile artistic foundation. The workshop was a bustling center of production, and young artists like Cesare would have participated in various stages of creating paintings, from preparing canvases and grinding pigments to executing less critical parts of commissioned works.

This period of study under Guercino was pivotal. It instilled in Cesare a profound understanding of drawing – the cornerstone of Bolognese artistic practice, heavily emphasized by masters like the Carracci (Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico Carracci) whose academy had revolutionized art training in Bologna decades earlier. Guercino himself was a prolific draftsman, and this emphasis on drawing as a tool for thought and composition was passed down to his nephews.

The Gennari Workshop: Continuation and Legacy

The death of Guercino in 1666 marked a turning point for Cesare and his brother Benedetto II. As Guercino's designated heirs, they inherited his substantial artistic estate, which included not only his studio, equipment, and ongoing commissions but also an invaluable collection of his paintings and, crucially, thousands of his drawings. This inheritance placed a significant responsibility on their shoulders: to manage this legacy and to continue the workshop's operations.

Cesare and Benedetto II jointly managed the "Casa Gennari." While Benedetto II would later embark on an international career, spending considerable time in the courts of France and England, Cesare largely remained in Bologna and Cento, anchoring the Italian base of their operations. Their collaboration was essential in fulfilling outstanding commissions and in producing new works that often emulated Guercino's popular style, catering to a market familiar with and desirous of his artistic language. The brothers were not mere copyists; they were skilled artists who adapted Guercino's manner to their own sensibilities and to the evolving tastes of the late 17th century.

A significant aspect of their role was the preservation and organization of Guercino's vast collection of drawings. These drawings, ranging from quick sketches to highly finished compositional studies, were a testament to Guercino's creative process and were highly sought after. The Gennari brothers understood their value, both artistic and monetary, and their stewardship ensured that a large portion of this graphic treasure survived, eventually finding its way into major collections like the Royal Collection Trust in England.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Cesare Gennari's artistic style is firmly rooted in the tradition of Guercino, yet it possesses its own distinct characteristics. He absorbed his uncle's mastery of light and shadow, his ability to convey emotion, and his skill in creating dynamic yet balanced compositions. However, compared to Guercino's often more vigorous and dramatic early works, Cesare's paintings can exhibit a softer touch, a more delicate modeling of forms, and a palette that sometimes leans towards brighter, more luminous hues, reflecting the later tendencies of Guercino himself and the general shift in Baroque aesthetics towards a more classical refinement.

He excelled in various genres. Religious subjects formed a significant part of his output, a staple for artists of the period catering to church commissions and private devotional needs. His depictions of saints and biblical narratives often convey a gentle piety and a refined sensibility. Portraiture was another area where Cesare demonstrated considerable skill. He was adept at capturing a sitter's likeness while imbuing the portrait with a sense of dignity and character, often employing the rich textures and subtle interplay of light favored in Bolognese portraiture.

While the provided information mentions a particular skill in landscape painting, it's more accurate to say that, like Guercino, Cesare was capable of rendering beautiful landscape elements, often as backgrounds to his figural compositions. Pure landscape painting as a primary genre was less common for him than for specialized Northern European artists, but the Bolognese tradition, starting with Annibale Carracci, had a strong landscape component, and Cesare certainly continued this. His landscapes, when they appear, are often idyllic and imbued with a soft, atmospheric light.

One interesting, though less central, aspect mentioned in the source material is his engagement with "humorous paintings" or caricatures. Guercino himself was known for his "disegni scherzosi" (jocular drawings), and it's plausible that Cesare continued this tradition within the workshop. Caricature was gaining popularity as a genre, and artists like Pier Leone Ghezzi would later become famous for it in Rome. The mention of a caricature of a priest from the San Tommaso church, with exaggerated features, suggests an engagement with this more informal and satirical side of art.

Representative Works

Cesare Gennari's oeuvre includes a range of works that showcase his talents. While a comprehensive catalogue is extensive, several key pieces highlight his style and thematic preoccupations:

_Saint Mary Magdalene de' Pazzi_: This altarpiece, mentioned in the provided text, is a fine example of his religious painting. The depiction of the Carmelite mystic would have required a sensitive portrayal of spiritual ecstasy, a theme common in Baroque art, famously tackled by artists like Gian Lorenzo Bernini in sculpture. Cesare's approach would likely combine devotional intensity with a refined execution.

_Allegoria della Pace (Allegory of Peace)_ (reportedly 1661): Allegorical subjects were popular in the Baroque period, allowing artists to convey complex ideas through symbolic figures. A depiction of Peace, possibly commissioned to commemorate a treaty or express a desire for tranquility, would feature personifications and attributes rendered with clarity and grace. This work, if dated to 1661, would have been created during Guercino's lifetime, showcasing Cesare's developing skills.

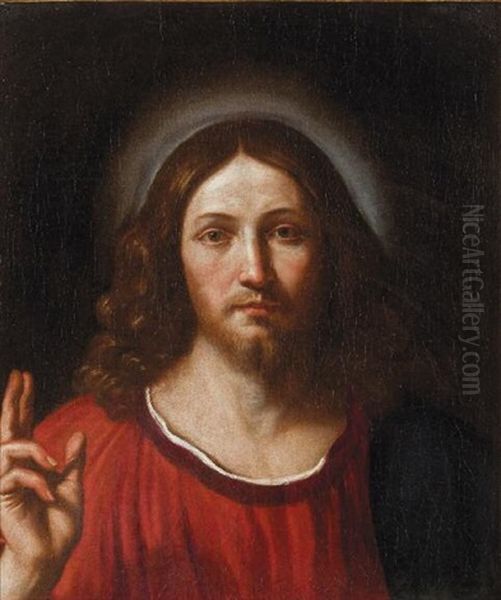

_Cristo benedicente (Christ Blessing)_ (reportedly 1660s): This intimate devotional image of Christ offering a blessing is a common theme. Cesare's interpretation would likely focus on a compassionate and serene portrayal, using subtle lighting to highlight Christ's features and convey a sense of divine presence. Such works were sought after for private chapels and personal devotion.

_Portrait d'une musicienne (Portrait of a Musician)_ (reportedly 1675-1688): Portraits of musicians offered artists the chance to combine likeness with an indication of the sitter's talents and social standing. The inclusion of a musical instrument would add a layer of iconographic interest and allow for the depiction of varied textures. This work, from his mature period, would demonstrate his skill in capturing both physical appearance and inner character.

_Ritratto di gentildonna con bambino (Portrait of a Noblewoman with Child)_ (reportedly c. 1680): This type of portrait emphasizes lineage, maternal affection, and social status. Cesare would have focused on the rich attire of the noblewoman, the tender interaction with the child, and an overall air of aristocratic elegance, following a tradition well-established by artists like Anthony van Dyck in other parts of Europe, and by Italian masters.

_Two putti supporting a medallion portrait of Guercino_: This work is a clear homage to his master. The use of putti, common allegorical figures, to present the image of Guercino underscores Cesare's reverence and his role as a continuer of his uncle's legacy. It's a piece that speaks directly to the artistic lineage and the familial bonds within the Casa Gennari.

It's also noted that some of Cesare's works were occasionally misattributed to Guercino, such as an "Allegory of Charity." This is not uncommon for workshop members who closely emulated their master's style and is, in a way, a testament to Cesare's skill in capturing the essence of Guercino's art.

The Broader Artistic Context and Contemporaries

Cesare Gennari operated within the vibrant artistic milieu of Bologna, which, since the late 16th century with the Carracci reform, had been a leading center of Italian painting. This tradition emphasized strong drawing, naturalism tempered by classicism, and emotional expressiveness. By Cesare's time, the High Baroque was flourishing, with artists across Italy exploring dynamic compositions, rich color palettes, and dramatic effects.

His primary influence was, of course, Il Guercino. However, the artistic environment of Bologna and Emilia-Romagna was populated by many other talented individuals. Carlo Cignani (1628-1719) was a dominant figure in Bolognese painting during the latter half of the 17th century, known for his elegant, classical style that influenced a generation. Lorenzo Pasinelli (1629-1700), another prominent Bolognese contemporary, developed a style characterized by soft sfumato and rich color, also drawing from Venetian influences. While the source text suggests Pasinelli might have been Cesare's student, it's more likely they were contemporaries, with Pasinelli himself being a significant master who taught artists like Donato Creti (1671-1749) and Giovanni Gioseffo dal Sole (1654-1719).

Other notable painters from the region or whose influence was felt include Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665), a prodigious talent who, despite her short life, ran a successful studio in Bologna. Earlier figures like Guido Reni (1575-1642) and Domenichino (1581-1641), key pupils of the Carracci, had established a powerful classical tradition that continued to resonate. The legacy of Francesco Albani (1578-1660), another Carracci follower known for his mythological landscapes, also formed part of the artistic backdrop.

While Cesare's brother, Benedetto Gennari II, gained international exposure, working for King Charles II and James II in England (where he would have been aware of court painters like Peter Lely and later Godfrey Kneller) and for Louis XIV in France (the era of Charles Le Brun), Cesare's career was more rooted in Italy. Nevertheless, the Gennari workshop, through Benedetto's travels and its established reputation, did participate in a broader European artistic network. The demand for Italian art, particularly from the Bolognese school, remained strong.

The mention of Antonio Zanetti (1689-1767) in relation to humorous drawings is interesting. Zanetti was a Venetian engraver, critic, and collector, known for his interest in caricatures and for publishing collections of them. If Cesare produced such works, they might have been known to collectors like Zanetti, or Zanetti might have engraved them, contributing to their dissemination.

International Connections and Misunderstandings

The provided information suggests Cesare Gennari had significant international activity, including painting for Louis XIV and the English courts. However, art historical consensus attributes these extensive international travels and commissions primarily to his brother, Benedetto Gennari II. Benedetto spent over a decade in England (c. 1674-1688) and also worked in Paris. It was Benedetto who became a court painter to Charles II and James II, and who fulfilled commissions for the French aristocracy.

Cesare, while undoubtedly involved in the production of works that may have been exported or commissioned by foreign patrons through the family workshop, primarily remained the anchor of the Gennari studio in Italy. This distinction is important for historical accuracy. The "Casa Gennari" operated as a collective to some extent, and works emerging from it would bear the family's stylistic imprint, but the direct courtly engagements abroad were largely Benedetto II's domain. Cesare's contribution was vital in maintaining the workshop's output and quality in Italy, ensuring the Gennari name continued to be associated with excellence.

Legacy and Conclusion

Cesare Gennari died in Bologna in 1688, the same year his brother Benedetto II returned to Italy after the Glorious Revolution in England. His life was dedicated to art, lived largely within the orbit of his great uncle, Guercino. His primary legacy lies in his role as a faithful and skilled continuer of Guercino's artistic tradition. He, along with his brother, ensured that the workshop remained productive and that Guercino's invaluable collection of drawings was preserved for posterity.

As an artist in his own right, Cesare Gennari produced a substantial body of work characterized by technical proficiency, a refined aesthetic, and a gentle emotional sensibility. His religious paintings, portraits, and allegorical scenes contributed to the rich artistic production of the Bolognese school in the late Baroque period. While perhaps not possessing the revolutionary genius of Guercino or the Carracci, Cesare was a master craftsman and a sensitive interpreter of the artistic currents of his time. His paintings are found in churches and collections, bearing witness to a career dedicated to beauty and devotion, firmly establishing his place as an important, if sometimes overlooked, painter of the Italian Seicento. His dedication to the "Casa Gennari" ensured that the artistic fire lit by Guercino continued to burn brightly through the next generation.