The Venetian Republic during the High Renaissance was a crucible of artistic innovation, a city shimmering with wealth, trade, and a unique cultural identity that fostered a distinct school of painting. Amidst luminaries like Titian, Giorgione, and Tintoretto, numerous other talented artists contributed to the rich tapestry of Venetian art. Among them, Bernardino Licinio (circa 1489 – circa 1565) carved out a significant niche, particularly celebrated for his insightful portraits and compelling religious compositions. Though perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, Licinio was a highly skilled painter who absorbed the prevailing artistic currents, developing a style that resonated with patrons and left a lasting mark on the Venetian artistic landscape.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in the Veneto

Bernardino Licinio is believed to have been born around 1489 in Poscante, a small village near Bergamo, which was then part of the Venetian mainland territories (Terraferma). This Bergamasque origin is significant, as the region produced several notable artists who would make their careers in Venice, bringing with them a certain Lombard realism that could temper the more idealized Venetian aesthetic. While details of his earliest training are scarce, it is widely accepted that he relocated to Venice, the vibrant heart of the Republic's artistic and commercial life, to pursue his career.

His familial connections likely played a role in his artistic development. He is often identified as the nephew of Paris Bordone by some older sources, though more modern scholarship suggests a closer artistic kinship, and perhaps even a familial link, to the Pordenone workshop. Specifically, he is sometimes thought to be related to Giovanni Antonio Pordenone (c. 1483/84 – 1539), a major figure in Venetian and Friulian painting known for his dynamic, muscular figures and dramatic compositions. Some accounts even suggest Licinio might have been a pupil or associate of Pordenone, whose robust style, influenced by Roman High Renaissance masters like Michelangelo, offered a powerful alternative to the softer, more poetic vein of Giorgione or early Titian. An early education in Friuli, Pordenone's heartland, is also a possibility, which would further cement this connection.

Venice in the early 16th century was an electrifying environment for an aspiring artist. The legacy of Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430 – 1516), the veritable father of Venetian painting, was still palpable, his luminous colors and gentle piety having set a high standard. Young titans like Giorgione (c. 1477/78 – 1510) and Titian (c. 1488/90 – 1576) were revolutionizing painting with their emphasis on colorito (color and painterly application) over disegno (drawing and design), their atmospheric effects, and their psychologically nuanced portrayals. Licinio would have been immersed in this world, absorbing these influences while forging his own artistic path.

Development of an Artistic Style: Influences and Individuality

Bernardino Licinio’s style is firmly rooted in the Venetian tradition of the High Renaissance. He demonstrated a keen understanding of the principles that defined the school: rich, warm color harmonies, a sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and a focus on the human element, whether in devotional scenes or portraiture. His work shows an openness to various influences, reflecting the dynamic artistic exchanges of the period.

The impact of Giorgione is discernible in some of Licinio's works, particularly in the softness of modeling, the introspective mood of certain figures, and the occasional poetic ambiguity that characterized Giorgione's masterpieces like The Tempest or the Concert Champêtre (the latter now often attributed to Titian). This Giorgionesque quality can be seen in the gentle rendering of flesh tones and the subtle interplay of light and shadow.

Titian, a towering figure whose career spanned much of Licinio's own, was an unavoidable influence. Titian's mastery of color, his ability to capture the texture of fabrics and the vitality of his sitters, set a benchmark for all Venetian painters. Licinio, like many others, learned from Titian's innovations in portraiture and his grand religious compositions, such as Titian's own Assumption of the Virgin in the Frari Church, a work of groundbreaking dynamism.

Another significant influence was Palma Vecchio (c. 1480 – 1528), a fellow Bergamasque who achieved great success in Venice. Palma was renowned for his sacre conversazioni (holy conversations, depicting the Virgin and Child with saints) and his idealized portrayals of beautiful, often blonde, Venetian women, as seen in works like The Three Sisters. Licinio’s compositions, particularly his group portraits and some religious scenes, often share a similar compositional balance and a comparable warmth of palette with Palma's work. The full-bodied figures and serene, pastoral mood found in Palma's art find echoes in Licinio's oeuvre.

The aforementioned Giovanni Antonio Pordenone also left a mark. If Licinio did indeed spend time in Pordenone's circle, he would have been exposed to a more vigorous, muscular, and dramatically charged style. While Licinio's temperament generally leaned towards a more composed and less overtly dramatic presentation, the solidity and presence of his figures might owe something to Pordenone's powerful example.

Licinio synthesized these influences into a personal style that was competent, often deeply felt, and commercially successful. He was not an innovator on the scale of Titian or Tintoretto, but he was a skilled practitioner who understood the desires of his patrons for portraits that conveyed status and personality, and for religious works that inspired devotion. His brushwork could be delicate, particularly in rendering flesh and fabrics, and he had a good sense of compositional arrangement, often favoring balanced, harmonious groupings.

Thematic Focus: Portraits, Religious Narratives, and Group Dynamics

Bernardino Licinio’s artistic output was diverse, encompassing the main genres popular in Venice at the time, but he particularly excelled in portraiture and religious scenes, often imbued with a strong sense of human interaction.

Portraiture: Capturing Venetian Society

Licinio was a sought-after portraitist. His portraits range from single figures to complex family groups, a genre in which he was particularly adept. These works provide a fascinating glimpse into Venetian society, depicting merchants, professionals, and their families. He had a talent for capturing a likeness while also conveying a sense of the sitter's social standing and inner life.

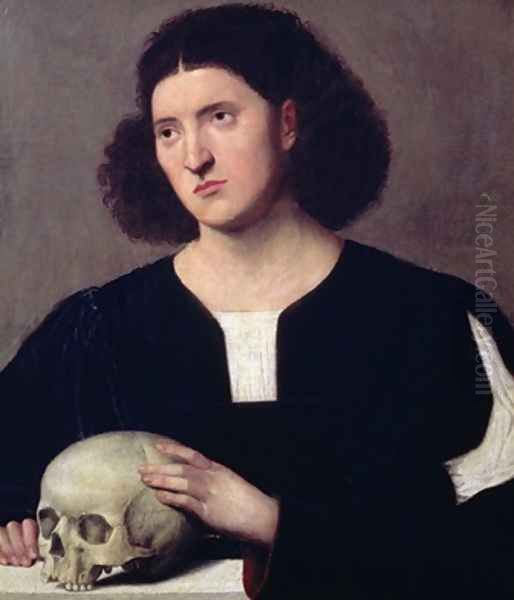

His individual portraits, such as the Portrait of Stefano Nani (National Gallery, London) or the Portrait of a Young Man with a Skull (Uffizi Gallery, Florence), often show the sitter in a three-quarter view, a format popularized by Netherlandish painters and adopted by Venetians. The Uffizi portrait, with its memento mori symbolism, reflects a common Renaissance theme of contemplating mortality. He often paid close attention to the rendering of costume, an important indicator of wealth and status in fashion-conscious Venice.

Family portraits were a particular strength. Works like Arrigo Licinio (the artist's brother) and his Family (Borghese Gallery, Rome) are notable for their complex arrangements and the sense of familial connection they convey. These group portraits often include multiple generations and highlight the importance of lineage and domesticity. Licinio managed to balance the individual characterization of each family member with the overall harmony of the group. Another example, A Lady with a Book of Music and Three Children (often identified as from his workshop, National Gallery, London), showcases the intimate portrayal of family life, with music often playing a symbolic role representing harmony or education.

Religious Compositions: Devotion and Narrative

Licinio produced numerous religious paintings, including altarpieces and smaller devotional works for private patrons. His sacre conversazioni are typical of the Venetian tradition, often depicting the Virgin and Child enthroned or in a landscape, surrounded by saints. These works are characterized by their warm colors, soft lighting, and the gentle, human interaction between the figures. An example is the Madonna and Child with Saints Mark and Jerome (Frari Church, Venice), which demonstrates his ability to create a serene and devotional atmosphere.

His larger altarpieces, such as The Assumption of the Virgin, showcase his ability to handle more complex, multi-figure compositions. While perhaps not possessing the dramatic intensity of Titian's version, Licinio's interpretations are marked by a clear narrative, strong emotional content, and a rich Venetian palette. He also painted scenes like The Franciscan Martyrs, depicting episodes from religious history with a focus on the piety and suffering of the saints. These works served to inspire devotion and reinforce religious teachings.

Musical Scenes and Allegories

Like many Venetian artists, including Giorgione and Titian, Licinio occasionally depicted musical scenes. These could be integrated into family portraits or stand as independent compositions. Music in Venetian painting often carried allegorical meanings, symbolizing harmony, love, or the cultivated pursuits of the sitters. His depictions of figures with musical instruments contribute to the broader Venetian interest in the sensory and emotional power of music.

Notable Works and Their Significance

While a comprehensive list of Licinio's works is extensive, several stand out and are frequently cited to illustrate his style and contributions:

_Arrigo Licinio and his Family_ (c. 1535, Borghese Gallery, Rome): This is perhaps his most famous family portrait. It depicts his brother, a sculptor, with his wife Agnese, their son Fabio, and other family members. The composition is ambitious, with figures arranged in a dynamic yet cohesive group. The emotional connections between the family members are subtly conveyed, and the work stands as a testament to the importance of family in Venetian society and Licinio's skill in capturing these complex dynamics.

_Portrait of a Young Man with a Skull_ (c. 1525-1530, Uffizi Gallery, Florence): This striking portrait features a young man, possibly a scholar or humanist, gazing thoughtfully towards the viewer while resting his hand on a skull. The skull, a traditional memento mori, invites contemplation on the transience of life. Licinio’s rendering of the young man’s introspective expression and the rich textures of his clothing are characteristic of his portraiture.

_Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints_ (various versions, e.g., Frari Church, Venice; Accademia Carrara, Bergamo): Licinio produced several variations of this classic sacra conversazione theme. These works typically feature a serene Virgin Mary and Christ Child, flanked by carefully individualized saints. The compositions are balanced, the colors rich and harmonious, and the overall mood is one of quiet devotion. The version in the Frari, for example, shows the Madonna and Child with Saints Mark, Jerome, Andrew, John the Baptist, and another saint, demonstrating his ability to manage a multi-figure religious scene with clarity and grace.

_The Assumption of the Virgin_ (location varies, e.g., a version in the Basilica dei Frari, Venice, though sometimes debated): While Titian's Assumption in the Frari is the definitive masterpiece of this subject, Licinio also tackled this theme. His interpretations, while perhaps less overtly dramatic, would have focused on the Virgin's ascent, surrounded by apostles and angels, rendered with his characteristic warmth and attention to human emotion.

_Portrait of Stefano Nani_ (c. 1528, National Gallery, London): This half-length portrait shows a man identified by an inscription. He is presented with a direct gaze, conveying a sense of presence and authority. The handling of the fur-lined robe and the subtle modeling of the face are indicative of Licinio's skill in capturing both likeness and texture.

_An Artist and his Pupils_ (Alnwick Castle, Duke of Northumberland collection): This intriguing painting is believed to be a self-portrait of Licinio with his students. It offers a rare glimpse into the workings of an artist's studio in the Renaissance, showing the master instructing younger apprentices. The depiction of different ages and skill levels among the pupils adds to its documentary value.

Workshop, Students, and Artistic Collaborations

Like most successful Renaissance artists, Bernardino Licinio likely maintained an active workshop to help him fulfill commissions. The presence of assistants and pupils was standard practice, allowing for the production of multiple versions of popular compositions and the training of the next generation of artists. The painting An Artist and his Pupils strongly suggests his role as a teacher. Among his students may have been family members, including his nephew and possibly his own children, as well as younger members of his brother Arrigo's family. This practice of training relatives within the workshop was common, ensuring the continuation of artistic skills and workshop traditions.

While concrete evidence of extensive collaborations with major, named artists is somewhat limited, the artistic environment of Venice was one of constant interaction. Artists learned from each other, borrowed motifs, and sometimes worked on large-scale projects together. There is speculation that Licinio might have collaborated with Callisto Piazza da Lodi (c. 1500–1561), another Lombard artist active in the Veneto, on certain works, possibly including a marriage portrait. Given the stylistic similarities and potential workshop connections with Pordenone, it's also plausible that Licinio was involved in projects emerging from Pordenone's circle or adopted compositional designs developed within that sphere.

His relationship with his brother, Arrigo Licinio, a sculptor, is also noteworthy. The famous family portrait in the Borghese Gallery prominently features Arrigo, highlighting the artistic pursuits within the Licinio family. While direct artistic collaboration on specific pieces might be hard to prove, the shared artistic environment within the family would undoubtedly have fostered mutual influence and support.

Contemporaries and the Venetian Artistic Milieu

Bernardino Licinio operated within one of an exceptionally fertile artistic period in Venice. He was a contemporary of some of the greatest names in Western art.

Titian was, of course, the dominant figure, his long career setting the tone for much of Venetian painting. Jacopo Tintoretto (1518–1594) and Paolo Veronese (1528–1588), though slightly younger, rose to prominence during Licinio's later career, bringing new levels of dynamism, drama, and decorative splendor to Venetian art.

Other significant contemporaries included Lorenzo Lotto (c. 1480 – 1556/57), another artist with Bergamasque roots, known for his psychologically intense portraits and idiosyncratic religious works. Sebastiano del Piombo (c. 1485 – 1547) began his career in Venice, influenced by Giorgione, before moving to Rome and absorbing the influence of Michelangelo. Paris Bordone (1500–1571), if not a direct relative, was certainly a contemporary whose work, particularly his sensuous female figures and rich mythological scenes, contributed to the Venetian High Renaissance style. Bonifazio Veronese (Bonifazio de' Pitati, c. 1487–1553) ran a large and productive workshop, creating many narrative paintings and sacre conversazioni that were highly popular. Andrea Schiavone (c. 1510/15 – 1563), influenced by Parmigianino and Mannerism, brought a different stylistic flavor to Venice. Jacopo Bassano (c. 1510 – 1592) and his workshop, based in Bassano del Grappa on the mainland but deeply connected to Venice, developed a distinctive style known for its rustic genre scenes and dramatic nocturnal effects.

In this competitive environment, Licinio carved out his own space. He may have competed for commissions with artists like Pordenone, particularly in the earlier part of his career. The stylistic similarities and occasional misattributions between Licinio and Pordenone suggest a close artistic dialogue, whether as master-pupil or as friendly rivals. If Licinio was indeed associated with Giovanni Bellini's studio in his formative years, as some older theories proposed (though less commonly held now), he would have been part of a generation of artists emerging from that foundational workshop, each striving to make their mark.

Challenges in Attribution and Scholarly Debates

The study of Bernardino Licinio's oeuvre is not without its challenges, particularly concerning attribution. His style, while distinctive, shares characteristics with several contemporaries, leading to historical confusion.

The most significant area of debate has been the differentiation of his works from those of Giovanni Antonio Pordenone and his workshop. Some of Licinio's more robust and dynamically composed pieces have, at times, been attributed to Pordenone, while conversely, some less characteristic works by Pordenone might have been assigned to Licinio. This overlap underscores their close artistic relationship but complicates the precise definition of each artist's body of work.

Furthermore, the output of Licinio's own workshop, where assistants would have replicated compositions or worked in his style, can make it difficult to distinguish autograph works from studio productions. This is a common issue for successful Renaissance artists who managed busy workshops.

Scholarly opinion on Licinio's artistic merit has also varied. Some critics have pointed to occasional "clumsiness" in drawing or proportion in certain works, or a perceived lack of the profound innovation seen in his most famous contemporaries. However, such criticisms often arise from comparing him to a few exceptional geniuses rather than evaluating him within the broader context of competent and highly skilled professional artists of his time. His best works demonstrate considerable technical skill, a fine sense of color, and an ability to convey character and emotion effectively.

The depiction of women in his paintings, particularly in scenes involving music or family groups, has also been a subject of art historical discussion, reflecting broader Renaissance attitudes towards gender roles, female education, and the representation of women in art. These images can be interpreted in various ways, sometimes highlighting female accomplishments and other times reflecting societal expectations or the male gaze.

The relative scarcity of detailed biographical information—common for many artists of this period who were not as extensively documented as figures like Michelangelo by Vasari—also means that aspects of his life, training, and career progression remain somewhat speculative, relying on stylistic analysis and the few surviving documents.

Later Career, Death, and Legacy

Bernardino Licinio remained active as a painter in Venice until at least the late 1540s, with some sources suggesting activity into the 1550s. The exact date of his death is uncertain but is generally placed around 1565 in Venice. By this time, the Venetian art scene was increasingly dominated by the grand styles of Titian in his later phase, Tintoretto, and Veronese.

Licinio's legacy lies in his contribution to the Venetian tradition of portraiture and religious painting. He was a skilled practitioner who successfully navigated the competitive art market of his day, producing a substantial body of work that was appreciated by his patrons. While he may not have been a radical innovator, he effectively synthesized the key elements of the Venetian High Renaissance style, creating works characterized by their warmth, humanity, and rich coloration.

His family portraits are particularly important, offering valuable insights into Venetian domestic life and social structures. His religious works served the devotional needs of both public and private patrons, rendered with a sincerity and competence that made them effective vehicles for spiritual contemplation.

Today, Bernardino Licinio's paintings are found in major museums and collections around the world, including the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the National Gallery in London, the Borghese Gallery in Rome, the Accademia in Venice, and the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, among others. His work continues to be studied by art historians for its intrinsic qualities and for what it reveals about the artistic culture of 16th-century Venice. He stands as a significant representative of the many talented artists who, while perhaps operating in the shadow of giants, played a crucial role in shaping the rich and diverse landscape of Renaissance art.

Conclusion: Bernardino Licinio's Place in Art History

Bernardino Licinio was a notable and productive painter of the Venetian High Renaissance, a period of extraordinary artistic ferment. Born in Bergamasque territory but making his career in the heart of La Serenissima, he absorbed the influences of the great masters of his time, including Giorgione, Titian, Palma Vecchio, and potentially Pordenone, to forge a style that was both accomplished and appealing. He excelled in portraiture, capturing the likenesses and social standing of Venetian citizens and their families with sensitivity and skill, and his religious paintings, particularly his sacre conversazioni and altarpieces, were imbued with the characteristic Venetian warmth, color, and humanism.

While not an artist who dramatically altered the course of art history in the manner of a Leonardo da Vinci or a Michelangelo, Licinio represents the high level of craftsmanship and artistic understanding that permeated Venetian art during this golden age. He successfully met the demands of his patrons, creating works that were both aesthetically pleasing and functionally effective, whether for private devotion, public display, or personal commemoration. His paintings offer a valuable window into the visual culture of 16th-century Venice, reflecting its values, its piety, and its appreciation for the beauty of the human form and the richness of the painted surface. As such, Bernardino Licinio remains an important figure for understanding the breadth and depth of the Venetian school, a testament to the enduring power of a tradition that masterfully blended color, light, and emotion.