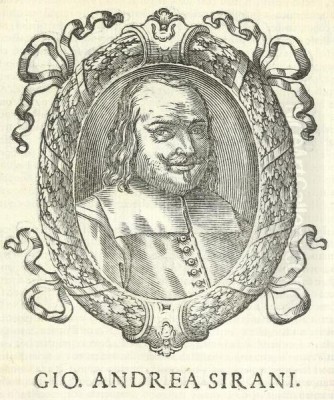

Giovanni Andrea Sirani (1610-1670) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant artistic milieu of 17th-century Bologna. A painter, art dealer, and the patriarch of an artistic dynasty, Sirani’s career was deeply intertwined with the towering figures of his time, most notably his master, Guido Reni. While his own considerable talents were occasionally eclipsed by Reni's fame or later by that of his prodigiously gifted daughter, Elisabetta Sirani, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized Giovanni Andrea's distinct contributions to the Bolognese School and the broader Italian Baroque movement. His journey reflects the dynamic interplay of influence, innovation, and the complex legacy of an artist who both absorbed and shaped the artistic currents of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Born in Bologna on September 4, 1610, Giovanni Andrea Sirani was immersed in art from a young age. His initial training likely came from his father, though details of this early instruction are sparse. Bologna, at this time, was a crucible of artistic innovation. The legacy of the Carracci – Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico – had firmly established the city as a center for a reformed, more naturalistic approach to painting, moving away from the perceived artificiality of late Mannerism. Their Accademia degli Incamminati had trained a generation of artists who would dominate Italian art, including figures like Domenichino, Francesco Albani, and, crucially for Sirani, Guido Reni.

It was under the tutelage of Guido Reni that Giovanni Andrea Sirani's artistic identity truly began to form. Reni, by then one of Italy's most celebrated painters, ran a large and busy workshop. Sirani became not just a student but a trusted assistant, absorbing Reni's refined classicism, his elegant figure types, and his sophisticated handling of color and light. This apprenticeship was foundational, shaping Sirani's technical skills and his aesthetic sensibilities. He learned the meticulous preparation, the careful drawing (disegno), and the layered painting techniques that characterized the Bolognese tradition.

The Enduring Influence of Guido Reni

Guido Reni's impact on Giovanni Andrea Sirani cannot be overstated. For much of his early to mid-career, Sirani worked closely with his master, assisting on major commissions and imbibing Reni's evolving style. Reni himself had moved through various stylistic phases, from an early Caravaggesque naturalism to a more idealized, classical manner, and later, in his "second style," towards a lighter palette, softer forms, and an almost ethereal quality. Sirani was particularly adept at emulating this later style, so much so that many of his works from this period were, and sometimes still are, misattributed to Reni.

This close association meant that Sirani was involved in the creation of numerous works that bore Reni's name, learning firsthand the master's approach to composition, religious iconography, and mythological narrative. He would have witnessed Reni's interactions with powerful patrons, including cardinals and nobility, gaining insight into the business side of art. The workshop system of the Baroque era often involved significant contributions from assistants, and Sirani's role was clearly substantial, indicating a high level of trust and skill. He was not merely a copyist but an active participant in Reni's artistic production, a fact that speaks volumes about his capabilities even before he fully established his independent career.

Forging an Independent Path: Light, Shadow, and Realism

Following Guido Reni's death in 1642, Giovanni Andrea Sirani stepped more fully into his own. He inherited a portion of Reni's studio materials and, more importantly, a reputation as one of his foremost pupils. This period marked a gradual but discernible shift in Sirani's style. While the elegance and grace of Reni remained a bedrock, Sirani began to explore a more robust and dramatic mode of expression.

A key development was his increasing engagement with the legacy of Caravaggio. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, though deceased for decades, continued to exert a powerful influence through his revolutionary use of tenebrism – dramatic contrasts of light and shadow – and his unidealized, often gritty, realism. While Reni himself had an early Caravaggesque phase, Sirani's later works show a renewed interest in these strong chiaroscuro effects, lending his figures a greater sense of volume and his scenes a heightened emotional intensity. This was not a wholesale adoption of Caravaggism, as seen in artists like Bartolomeo Manfredi or Jusepe de Ribera, but rather a selective integration of its expressive potential into his established Bolognese framework. His figures became more solid, their gestures more pronounced, and the interplay of light and dark more central to the narrative impact of his compositions. This evolution demonstrated his capacity to synthesize different artistic currents, moving beyond mere imitation of his master.

Major Themes and Representative Works

Giovanni Andrea Sirani's oeuvre encompassed a range of subjects typical of the Baroque period, including religious scenes, mythological narratives, and portraiture. His works were primarily destined for churches and public buildings in Bologna and the surrounding region, as well as for private collectors.

Among his notable religious paintings, works like "The Scourging of Christ" exemplify his mature style. Here, the dramatic use of light highlights Christ's suffering, while the muscularity and dynamism of the figures show a departure from the more serene classicism of Reni, leaning towards a more visceral realism. The composition is carefully structured, yet imbued with a palpable sense of movement and emotional force.

Another significant work often cited is "Lucretia." The subject of the Roman noblewoman Lucretia, who chose suicide over dishonor, was popular in the Baroque for its dramatic potential and moral overtones. Sirani's depiction would have focused on the emotional turmoil and tragic resolve of the heroine, likely employing his characteristic blend of classical form and heightened emotional expression, possibly with strong chiaroscuro to underscore the drama. Such paintings allowed artists to explore intense human feeling within an accepted historical or mythological framework.

The painting "Madonna and Child with Saints" (or variations like "The Madonna of the Hut" as sometimes translated) would have been a staple of his religious output. These compositions allowed for tender depictions of the Virgin and Child, often accompanied by patron saints, reflecting the devotional needs of his patrons. Sirani's skill in rendering drapery, serene expressions, and balanced compositions would have been evident in such works. He managed to convey both the divine nature of the figures and their human accessibility.

His "Allegory of Painting and Music" is an interesting example of a more humanistic theme. Depicting two female figures, one engaged in painting and the other in singing, this work celebrates the sister arts. Such allegories were common, reflecting the era's intellectual currents and the elevated status of the arts. Sirani's treatment would have combined graceful figures with symbolic attributes, showcasing his ability to handle complex iconographic programs.

His works often featured complex structures and lively figures, demonstrating a departure from the softer lines that became popular later in the 18th century with artists like Rosalba Carriera or Jean-Antoine Watteau. Sirani's figures possessed a tangible presence, a solidity rooted in the Bolognese emphasis on drawing and anatomical understanding, further enhanced by his sophisticated use of light.

The Sirani Workshop: Art, Commerce, and Family

Beyond his personal artistic output, Giovanni Andrea Sirani was a successful art dealer and the head of a thriving workshop. This was a common model for established artists, allowing them to manage larger commissions, train pupils, and engage in the lucrative art market. Sirani's business acumen was evidently well-developed, enabling him to support his family and maintain a prominent position in Bologna's artistic community.

His workshop became a family enterprise. He trained his three daughters – Elisabetta, Anna Barbara, and Barbara – all of whom became painters. This was particularly noteworthy in an era when professional artistic careers for women were rare, though not unheard of, with predecessors like Lavinia Fontana (also from Bologna) and Sofonisba Anguissola paving the way. Sirani's decision to train his daughters professionally demonstrates a progressive attitude and a recognition of their talent. He provided them with the rigorous training typically reserved for male apprentices, equipping them with the skills necessary to succeed.

Elisabetta Sirani: A Daughter's Brilliance

The most famous of his children was Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665). A true prodigy, Elisabetta quickly absorbed her father's teachings and developed a remarkably fluid and rapid painting style. Her talent was so prodigious that she began receiving independent commissions at a young age. As Giovanni Andrea suffered increasingly from gout, a painful condition that eventually incapacitated his hands and prevented him from painting, Elisabetta effectively took over the management of the family workshop.

Elisabetta became one of Bologna's most celebrated artists, known for her speed, the quality of her work, and her public demonstrations of painting. She specialized in historical and religious subjects, often featuring strong female heroines, and her style, while rooted in her father's teachings and the Reni tradition, possessed its own distinct energy and grace. Tragically, Elisabetta died at the young age of 27, but in her short career, she produced an astonishing volume of work and even established an academy for female artists in Bologna – a pioneering achievement. While Giovanni Andrea was undoubtedly proud of his daughter's success, her meteoric rise and enduring fame have, at times, led to his own contributions being somewhat overshadowed in popular art historical narratives. However, it was his initial training and support that provided the foundation for her extraordinary career. Other notable female artists of the period, like Artemisia Gentileschi, often faced greater struggles for recognition without such strong familial artistic support.

Later Years, Health, and Continued Influence

Giovanni Andrea Sirani's later years were marked by declining health. The severe gout that afflicted him progressively limited his ability to paint, a cruel fate for an artist whose livelihood depended on his hands. Despite this, he remained an influential figure in Bologna's art scene. He continued to guide his daughters and other students, and his expertise as a connoisseur and art dealer would have remained valuable.

His role as an educator extended beyond his own family. By fostering female talent within his own workshop, he contributed significantly to the artistic education available in Bologna, challenging, to some extent, the male-dominated structures of the art world. His legacy was thus not only in his own canvases but also in the artists he nurtured. He passed away in Bologna on May 21, 1670, at the age of 59.

Sirani's Place in the Bolognese School and Beyond

Giovanni Andrea Sirani occupies an important position within the Bolognese School of the 17th century. He was a direct artistic descendant of the Carracci reform through his master, Guido Reni. He upheld the Bolognese emphasis on strong drawing, balanced composition, and a certain classical restraint, even as he incorporated more dramatic, Caravaggesque elements.

He can be seen as a transitional figure, bridging the high classicism of Reni with the more robust naturalism that gained currency in the mid-Baroque. His contemporaries in Bologna included artists like Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri), who also masterfully blended classical ideals with dramatic lighting, and Alessandro Tiarini. Further afield, his work resonates with broader Baroque trends seen in artists like Pietro da Cortona in Rome, known for his exuberant ceiling frescoes, or even the more restrained classicism of French painters like Nicolas Poussin, who also spent significant time in Italy. Sirani's engagement with light and shadow connects him to a lineage that includes not only Caravaggio but also artists like Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter Artemisia.

Rediscovery and Reassessment

For a considerable time, Giovanni Andrea Sirani's artistic identity was somewhat subsumed by that of Guido Reni. The similarity in style, especially in works produced while Sirani was Reni's chief assistant, led to frequent misattributions. Furthermore, the dazzling, albeit brief, career of his daughter Elisabetta captured the historical imagination, sometimes deflecting attention from her father's own achievements.

However, modern art historical scholarship has undertaken a more nuanced reassessment of Giovanni Andrea Sirani. Through careful connoisseurship, archival research, and stylistic analysis, scholars have worked to disentangle his oeuvre from Reni's and to appreciate his individual artistic merits. His ability to evolve stylistically, his technical proficiency, and his role in fostering a new generation of artists, particularly female artists, are now more fully recognized. He is no longer seen merely as a follower of Reni but as an artist who made his own distinct contribution to the rich tapestry of Italian Baroque art. His works are valued for their skillful execution, their emotional depth, and their embodiment of the artistic dynamism of 17th-century Bologna.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Art and Family

Giovanni Andrea Sirani's life and career offer a fascinating window into the art world of Baroque Italy. As a student and principal assistant to Guido Reni, he was intimately connected to one of the era's giants. As an independent master, he forged a style that balanced classical elegance with dramatic intensity, reflecting the evolving tastes of his time. His workshop was not only a center of artistic production but also a nurturing ground for talent, most notably for his exceptionally gifted daughters.

While the brilliance of Reni and the poignant story of Elisabetta have often taken center stage, Giovanni Andrea Sirani's own artistic journey, his technical mastery, and his significant role as an educator and cultural figure in Bologna secure his place in the annals of art history. He was a vital link in the chain of Bolognese artistic tradition, an artist who absorbed the lessons of the past while engaging with the innovations of his present, leaving behind a body of work that continues to command respect and admiration. His story is a testament to the enduring power of artistic lineage, personal innovation, and the quiet but profound impact of a dedicated master.