Charles Ferdinand Ceramano stands as a notable figure in 19th-century European art, a Belgian painter who carved a distinct niche for himself primarily within the vibrant artistic milieu of France. Celebrated for his sensitive portrayals of animals, particularly sheep, and his evocative landscapes, Ceramano's work is deeply intertwined with the ethos of the Barbizon School, an artistic movement that championed realism and a profound connection with nature. His long and productive career saw him become a respected animalier, whose paintings continue to be appreciated for their tranquil beauty and technical skill.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in 1829, Charles Ferdinand Ceramano, whose original surname was Sermole, entered a world where artistic conventions were increasingly being challenged. While some sources suggest a birth year of 1831, the consensus among art historians points to 1829. His early life and artistic training in Belgium are not extensively documented, but it is clear that he was drawn to the burgeoning realist tendencies that were gaining traction across Europe. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, he eventually made his way to France, the epicenter of artistic innovation during the 19th century.

The decision to move to France, and specifically to immerse himself in the environment of Barbizon, was pivotal. This period was characterized by a shift away from the idealized and historical subjects favored by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Artists were increasingly turning their gaze to the everyday, to the landscapes of their surroundings, and to the lives of ordinary people and animals. This burgeoning interest in naturalism provided fertile ground for an artist with Ceramano's inclinations.

The Barbizon Influence and Charles Jacque

Ceramano's artistic identity was significantly shaped by his association with the Barbizon School. This informal group of painters, active from roughly the 1830s to the 1870s, congregated in and around the village of Barbizon, near the Forest of Fontainebleau. They were united by a desire to paint directly from nature (en plein air), capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, and depicting rural life with honesty and empathy. Key figures of this movement included Jean-François Millet, renowned for his dignified portrayals of peasant laborers; Théodore Rousseau, a master of landscape painting; Charles-François Daubigny, known for his river scenes; and Constant Troyon, who also excelled in animal painting, particularly cattle.

It was within this environment that Ceramano found a mentor and kindred spirit in Charles Jacque. Jacque was an established member of the Barbizon School, particularly acclaimed for his etchings and paintings of sheep, poultry, and rustic farm interiors. Under Jacque's guidance, Ceramano honed his skills in animal depiction and absorbed the Barbizon philosophy. He spent approximately four decades working in Barbizon, a testament to the profound impact this artistic community and its natural surroundings had on his oeuvre. This long tenure allowed him to deeply immerse himself in the rhythms of rural life, which became the central theme of his art. Other artists associated with Barbizon, such as Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña with his forest scenes and Jules Dupré with his dramatic landscapes, also contributed to the rich artistic tapestry that Ceramano became part of.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

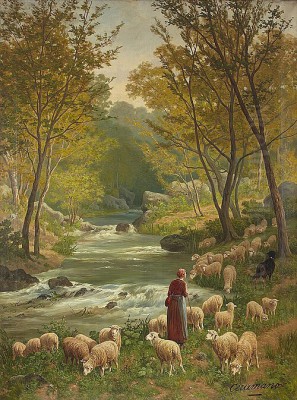

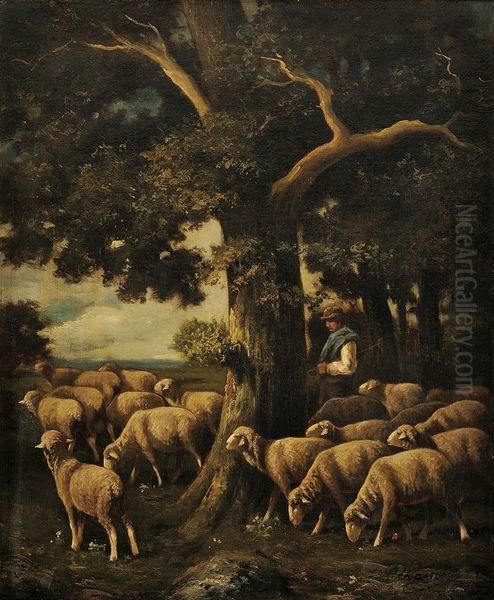

Ceramano's artistic style is characterized by a gentle realism, a meticulous attention to detail, and a warm, often idyllic, portrayal of his subjects. He specialized in animal painting, with sheep being his most recurrent motif. His canvases often depict flocks of sheep grazing peacefully in sun-dappled forests, resting in rustic barns, or being tended by solitary shepherds or shepherdesses. These scenes are imbued with a sense of tranquility and a deep affection for the pastoral way of life.

His technique involved careful observation, capturing the individual characteristics of the animals, the texture of their wool, and their natural postures. Unlike some animaliers who focused on the wild or dramatic aspects of animal life, such as Antoine-Louis Barye with his powerful sculptures of struggling beasts, Ceramano's interest lay in the domesticated and the serene. His landscapes, while serving as backdrops, are rendered with equal care, often featuring the distinctive light and foliage of the Forest of Fontainebleau. The interplay of light and shadow, a hallmark of Barbizon painting, is evident in his work, lending depth and atmosphere to his compositions.

His palette was typically rich yet subdued, favoring earthy tones, soft greens, and gentle blues, which enhanced the peaceful mood of his paintings. He worked primarily in oil on canvas or panel, mediums that allowed for the detailed rendering and subtle gradations of tone that his style demanded. His compositions are generally well-balanced, drawing the viewer's eye into a harmonious vision of rural existence.

Representative Works

Throughout his career, Charles Ferdinand Ceramano produced a significant body of work, with several paintings standing out as representative of his style and thematic preoccupations. While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be elusive, records from exhibitions and auctions provide insight into his most recognized pieces.

"Tending Her Flock" (often translated from titles like "Gardeuse de moutons") is a recurring theme and title variation in his work. These paintings typically feature a shepherdess, often young, watching over her sheep in a quiet pasture or woodland setting. The focus is on the harmonious relationship between the human figure and the animals, and the peaceful integration of both within the natural landscape.

"Les moutons à la bergerie" (Sheep in the Sheepfold or Sheep before the Shepherd's Hut) is another characteristic subject. These works often depict sheep gathered near or inside a rustic barn or shelter, sometimes with poultry sharing the space, as in "Sheep and poultry in a barn." These interior scenes allowed Ceramano to explore different lighting conditions, often with light filtering through doorways or cracks in the wooden structures, highlighting the textures of wool, straw, and aged wood.

"Le dormoir" (The Sleeping Place/Dormitory for Sheep), dated 1873, and "Berger et ses moutons" (Shepherd and his Sheep), dated 1872, are specific examples that have appeared in auction records, underscoring his consistent focus on these pastoral themes. "Le sommeil" (Sleep or The Sleepers) likely depicts animals or figures at rest, aligning with his penchant for tranquil scenes.

A painting titled "La Fête de Barbizon" (The Barbizon Festival) suggests a departure from his usual solitary animal scenes, potentially offering a glimpse into the communal life of the village that was so central to his artistic development. Such a piece would be valuable for understanding his broader engagement with the Barbizon community.

These works, and many others like them, were regularly exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon. The Salon was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts and the most important venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage in 19th-century France. Ceramano's consistent presence there indicates the acceptance and appreciation of his work by the art establishment and the public alike.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Ceramano's artistic journey unfolded during a dynamic period in French art. Beyond his direct mentor Charles Jacque and the core Barbizon painters like Millet, Rousseau, Daubigny, and Troyon, the broader art world was teeming with talent and diverse approaches.

The realist impulse that fueled Barbizon also found a powerful, and often more provocative, expression in the work of Gustave Courbet, who challenged academic conventions with his unflinching depictions of ordinary life and his bold technique. While Ceramano's realism was gentler, he shared with Courbet a commitment to representing the tangible world.

In the realm of animal painting, Rosa Bonheur was a towering figure, achieving international fame for her large-scale, meticulously detailed paintings of animals, such as "The Horse Fair." Her success demonstrated the significant public appetite for animal subjects. Ceramano, while perhaps not achieving Bonheur's level of widespread celebrity, contributed to this genre with his own distinct, more intimate vision. Other notable animal painters of the era included the Belgian artist Joseph Stevens, known for his depictions of dogs.

The Barbizon School's emphasis on plein-air painting and capturing the effects of light also laid some groundwork for the Impressionist movement, which emerged in the 1870s. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley took the practice of outdoor painting to new heights, focusing on subjective visual sensations and the transient qualities of light. While Ceramano remained rooted in the Barbizon tradition, the artistic currents of Impressionism were developing alongside his mature career.

In his native Belgium, contemporary artists included figures like Alfred Stevens (not to be confused with the British Alfred Stevens), who gained renown in Paris for his elegant genre scenes of fashionable women, and Henri de Braekeleer, who painted intimate and atmospheric interiors. Though their subject matter differed, they were part of the same generation of artists navigating the evolving European art scene.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Market Presence

Charles Ferdinand Ceramano's participation in the Paris Salon was a crucial aspect of his career. Acceptance into the Salon was a mark of professional achievement, offering artists visibility to critics, collectors, and the public. His regular inclusion signifies that his pastoral scenes and animal depictions resonated with contemporary tastes and met the standards of the Salon juries, at least for a significant period.

The enduring appeal of Ceramano's work is also evidenced by its continued presence in the art market. His paintings appear in auctions, and sales records, such as those for "Le dormoir" and "Berger et ses moutons," indicate that they command respectable prices. This demonstrates a sustained interest among collectors for his particular brand of Barbizon-influenced animal painting. The qualities that made his work popular in his lifetime—its technical proficiency, its gentle charm, and its evocation of a peaceful rural world—continue to attract admirers.

While he may not have been a radical innovator who dramatically altered the course of art history in the way that figures like Courbet or Monet did, Ceramano was a highly skilled and dedicated painter who made a significant contribution within his chosen genre. He was a respected member of the Barbizon artistic community and a successful exhibitor at the Salon, achievements that underscore his standing in the 19th-century art world.

Later Life and Legacy

Charles Ferdinand Ceramano passed away in 1909, leaving behind a substantial body of work that continues to celebrate the beauty of the natural world and the quiet dignity of pastoral life. His legacy is primarily that of a gifted animalier and a faithful adherent to the principles of the Barbizon School. He excelled in capturing the tranquil essence of the countryside, particularly the lives of sheep, which he rendered with both accuracy and affection.

His influence on subsequent art movements may have been indirect, part of the broader Barbizon School's impact on fostering realism and landscape painting. The Barbizon artists, as a collective, helped to shift the focus of art away from academic historicism towards a more direct engagement with contemporary life and nature. This paved the way for later movements, including Impressionism, even if individual artists like Ceramano did not themselves transition into these newer styles.

Today, Ceramano's paintings are appreciated for their artistic merit and as charming evocations of a 19th-century rural idyll. They offer a window into a world where the connection between humans, animals, and the land was central to existence. For collectors and enthusiasts of Barbizon art and animal painting, his works remain sought after for their serene beauty, their technical accomplishment, and their embodiment of a deep love for the pastoral tradition. He remains a testament to the enduring appeal of nature depicted with skill and heartfelt sincerity. His dedication to his craft over several decades in Barbizon solidifies his place as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, contributor to this important chapter in the history of art.