Auguste Bonheur, a name perhaps less instantly recognizable than that of his celebrated sister, Rosa, nonetheless carved a significant niche for himself within the bustling art world of 19th-century France. Born into an era of artistic transition, where Romanticism was ceding ground to Realism and Naturalism, Bonheur dedicated his career to the meticulous and heartfelt depiction of animals and landscapes. His work, characterized by its directness, clarity, and profound respect for the natural world, offers a window into the rural life and scenic beauty of France, rendered with a sincerity that continues to resonate. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of a painter who, while sometimes overshadowed, contributed meaningfully to the rich tapestry of French art.

Early Life and Artistic Lineage

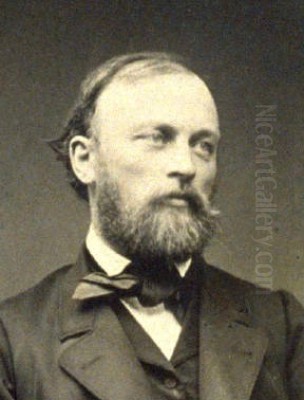

François Auguste Bonheur was born on November 4, 1824, in Bordeaux, a bustling port city in the Gironde region of southwestern France. Art was not merely a profession in the Bonheur household; it was a way of life. His father, Raymond Bonheur (1796-1849), was a respected landscape and portrait painter and an influential art teacher. His mother, Sophie Marquis (1797-1833), was a piano teacher, suggesting an environment rich in cultural pursuits. Auguste was one of four children, all of whom would pursue artistic careers. His elder sister, Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), would become one of the most famous female artists of the 19th century, renowned for her animal paintings. His younger brother, Isidore Jules Bonheur (1827-1901), became a notable animalier sculptor, and his youngest sister, Juliette Bonheur (1830-1891), also became a painter.

The early death of their mother when Auguste was just nine years old undoubtedly impacted the family. Raymond Bonheur, a proponent of Saint-Simonianism – a utopian socialist philosophy that advocated for gender equality – played a crucial role in his children's education, particularly encouraging his daughters' artistic ambitions in an era when such pursuits were often limited for women. Auguste's artistic training began formally under his father's tutelage. In 1842, he entered his father's studio, immersing himself in the foundational principles of drawing and painting. This familial apprenticeship provided him with a strong technical grounding and an early exposure to the prevailing artistic currents of the time.

A Shift Towards Nature: Animals and Landscapes

Initially, Auguste Bonheur explored portraiture and genre scenes, common subjects for aspiring artists. However, his true passion, much like his sister Rosa's, lay in the depiction of animals and the natural landscapes they inhabited. This shift was not uncommon among artists seeking alternatives to the grand historical and mythological themes favored by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The growing interest in everyday life and the unadorned beauty of nature, championed by the burgeoning Realist movement, provided fertile ground for artists like Auguste.

His approach was characterized by a desire for authenticity. He sought to capture the true essence of his subjects, whether the placid gaze of a cow, the rough texture of a sheep's fleece, or the dappled light filtering through a forest canopy. This commitment to verisimilitude led him to spend considerable time observing animals in their natural settings, studying their anatomy, movements, and behaviors. His landscapes, often serving as more than mere backdrops, were rendered with equal care, reflecting a deep appreciation for the specific character of the French countryside. He frequently depicted scenes from regions like Auvergne, Cantal, the Forest of Fontainebleau, the Pyrénées, and even ventured to Scotland, always seeking to capture the unique atmosphere and light of each location.

The Naturalist Style and Its Context

Auguste Bonheur's artistic style is firmly rooted in Naturalism and Realism, movements that gained prominence in France from the mid-19th century. Naturalism, often seen as an extension of Realism, emphasized detailed, objective representation based on empirical observation. Artists like Bonheur aimed to depict the world "as it is," without idealization or overt sentimentality, though a profound affection for their subjects often shone through. His technique was notable for its clarity and directness. Contemporaries observed that he consciously eschewed the "smoke, mist, and bitumen" – the dark, often artificially atmospheric glazes and pigments – that were common in more traditional or Romanticized landscape and animal paintings. Instead, he favored a brighter palette and a crisper rendering that highlighted the "soft gloss" of animal coats and the "freshness" of the natural environment.

This approach aligned him with the broader trends of the era. The Barbizon School painters, active from the 1830s near the Forest of Fontainebleau, were pivotal in popularizing landscape painting as a subject in its own right, emphasizing plein air (outdoor) sketching and a truthful depiction of rural scenery. Artists such as Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot paved the way for a more naturalistic vision. While Bonheur may not have been a formal member of the Barbizon group, his work shares their commitment to capturing the unembellished beauty of the French countryside. Similarly, the powerful Realism of Gustave Courbet, who famously declared he would only paint what he could see, challenged academic conventions and championed contemporary subjects. Auguste Bonheur's focus on rural life and animal subjects can be seen as part of this wider artistic current. His animal paintings also built upon a tradition of animaliers in French art, which included figures like Constant Troyon, another artist associated with the Barbizon School who excelled in depicting cattle.

Notable Works and Dominant Themes

Auguste Bonheur's oeuvre is rich with scenes of pastoral life. Cattle and sheep are recurrent subjects, often depicted grazing peacefully in meadows, drinking from streams, or gathered in farmyards. These were not generic representations; Bonheur imbued his animals with a sense of individual presence, capturing their placid strength and gentle nature. His landscapes, whether the rugged terrain of Auvergne or the lush pastures of Normandy, were rendered with a keen eye for topographical accuracy and atmospheric effect.

Among his representative works, titles often speak directly to his subject matter:

Cattle in a Meadow and Cattle Grazing in a Meadow showcase his skill in portraying livestock within their natural environment, likely focusing on the interplay of light on their hides and the surrounding foliage.

The Shepherd and His Flock and Sheep in a Farmyard would have allowed him to explore the textures of wool and the dynamics of a group of animals, a theme also explored by artists like Charles Jacque.

Landscape with Mountains in the Distance and Auvergne Landscape highlight his dedication to capturing specific regional characteristics. The Auvergne region, with its volcanic hills and distinct rural architecture, provided rich material for his brush.

Cattle Drinking at a Stream and Cattle Drinking are classic pastoral themes, offering opportunities to depict reflections in water and the natural postures of animals.

Oaks and Woodland suggests a focus on the majestic forms of trees and the intricate play of light and shadow within a forest setting, reminiscent of the Barbizon painters' deep engagement with forest interiors.

Studies like Cloud Study, Study of Three Sheep Heads, and Study of a Black Ram underscore his commitment to close observation and anatomical accuracy, essential groundwork for his larger compositions.

Cattle on the Banks of a River in Auvergne and Highland Cattle Scene (indicating his travels to Scotland) further demonstrate his interest in specific locales and breeds.

While the provided list includes Horses Ploughing in the Nivernais, this title is most famously associated with his sister Rosa Bonheur's monumental masterpiece, exhibited at the Salon of 1849. It's possible Auguste painted a work with a similar title or theme, or collaborated, but Rosa's version remains iconic. The shared thematic interest, however, underscores the family's deep connection to rural and animal subjects.

Salon Success and Official Recognition

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage in 19th-century France. Auguste Bonheur made his Salon debut in 1845, but it was in the 1850s and 1860s that he achieved significant acclaim. His work was consistently well-received by critics and the public. He was awarded a third-class medal at the Salon of 1852, followed by a second-class medal in 1859. His success culminated in a first-class medal in 1861, a significant honor that solidified his reputation.

Further official recognition came in 1867 when he was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour (Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur), France's highest order of merit. This award was a testament to his contributions to French art and his standing within the artistic community. His paintings were not only popular in France but also found an appreciative audience abroad, particularly in the Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It is noted that Queen Victoria herself requested a viewing of his work, indicating his international appeal. His paintings were sought after by collectors, and many found their way into prominent public and private collections.

The Bonheur Dynasty: Collaboration and Shadow

The Bonheur family was an artistic dynasty, and Auguste's career was inevitably intertwined with that of his siblings, most notably Rosa. Rosa Bonheur achieved international superstardom, a rare feat for any artist, let alone a woman in the 19th century. Her bold personality, unconventional lifestyle (including wearing men's attire, for which she had to obtain police permission, to facilitate her work in slaughterhouses and animal markets), and powerful animal paintings like The Horse Fair (1852-55) made her a larger-than-life figure.

Auguste and Rosa shared a deep artistic kinship. They both trained under their father, shared a passion for animal subjects, and possessed a similar commitment to anatomical accuracy and naturalistic representation. There are accounts of them collaborating on works, and their styles were often compared. Some critics even suggested that Auguste's handling could be "prettier" or more refined in certain aspects, though Rosa's work often possessed a greater sense of power and dynamism.

However, Rosa's immense fame inevitably cast a long shadow. While Auguste achieved considerable success and recognition in his own right, his name was, and often still is, mentioned in conjunction with his more famous sister. This is a common phenomenon in artistic families where one member achieves exceptional celebrity. It is a testament to Auguste's talent and perseverance that he established a distinct and respected career despite this familial context. His brother, the sculptor Isidore Jules Bonheur, also achieved renown, often collaborating with Rosa by creating sculptural versions of animals featured in her paintings. The family's collective dedication to animal art made the Bonheur name synonymous with the genre.

Travels, Inspiration, and Later Years

Like many landscape and animal painters of his time, Auguste Bonheur was an avid traveler. He understood that direct observation was paramount to capturing the truth of nature. His journeys took him to various picturesque regions of France. The Auvergne, with its ancient volcanic landscapes and distinctive breeds of cattle, was a favorite subject. The Forest of Fontainebleau, a mecca for the Barbizon painters, also drew him, as did the rugged beauty of the Pyrénées. These excursions provided him with a rich stock of motifs and a deep understanding of the interplay between animals and their environments. His travels even extended to the Scottish Highlands, whose dramatic scenery and hardy cattle offered new artistic challenges and inspirations.

His dedication to his craft was unwavering. However, his later life was marked by a period of ill health. After contracting typhoid fever, Auguste Bonheur sought a more secluded existence. He moved to Magny-les-Hameaux, a village in the Chevreuse Valley, southwest of Paris. Here, he lived a more reclusive life, somewhat akin to a hermit, though likely still engaged with his art. This retreat from the bustle of Parisian art life may have contributed to his somewhat quieter public profile in his final years compared to the enduring celebrity of his sister. Auguste Bonheur passed away in Paris on February 22, 1884, at the age of 59, leaving behind a significant body of work that celebrated the enduring beauty of the natural world.

Academic Evaluation and Enduring Influence

Academic and critical assessment of Auguste Bonheur's work has generally been positive, acknowledging his technical skill, his sincere and direct approach to nature, and his contribution to the Realist and Naturalist movements. He is praised for his ability to render the "soft, silky coats of his animals" and the "fresh, vibrant foliage" of his landscapes, achieved by his deliberate avoidance of artificial studio effects. His paintings are seen as honest and unpretentious, capturing a sense of tranquility and harmony in nature.

While often discussed in relation to Rosa, art historians recognize Auguste's individual merits. His work played a role in the broader shift towards Realism in French art. His straightforward depictions of rural life and his meticulous attention to detail contributed to the aesthetic that valued truthfulness and direct observation over academic idealism or Romantic emotionalism. His paintings, with their "simplicity, tranquility, and true reproduction of nature," are considered important examples of French Realist landscape and animal painting.

His influence, while perhaps not as widely transformative as that of figures like Courbet or Millet, was nonetheless felt. He provided a consistent and high-quality example of Naturalist animal and landscape painting that appealed to a broad public and influenced other artists working in similar genres. His success in France and abroad helped to popularize these themes. Today, his works are held in numerous museums and private collections, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Bordeaux Musée des Beaux-Arts, and various institutions in the United Kingdom and the United States. They continue to be appreciated for their technical finesse, their gentle charm, and their faithful portrayal of a 19th-century rural world. Other animal painters of the period, such as Jacques Raymond Brascassat or the Belgian Eugène Joseph Verboeckhoven, worked in similar veins, contributing to a strong European tradition of animal painting to which Auguste Bonheur was a significant French contributor. His legacy is that of a dedicated and skilled artist who, with quiet conviction, captured the essence of the animals and landscapes he loved.

Conclusion: A Distinct Voice in French Naturalism

Auguste Bonheur stands as a significant figure in 19th-century French art, a painter whose dedication to Naturalism and Realism produced a body of work celebrated for its honesty, technical skill, and profound appreciation for the rural world. Born into an extraordinary artistic family, he navigated his career with integrity, achieving notable success at the Salon and earning the prestigious Legion of Honour. While the colossal fame of his sister Rosa sometimes overshadowed his own achievements, Auguste's contributions to animal and landscape painting are undeniable. His meticulous depictions of cattle and sheep, set within carefully observed French landscapes, particularly those of Auvergne and Fontainebleau, reveal an artist deeply connected to his subjects. By eschewing artificiality and embracing a direct, clear style, he captured the authentic character of nature and rural life, aligning himself with the progressive artistic currents of his time alongside figures like Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Constant Troyon. His paintings remain a testament to his talent and offer a serene and enduring vision of the 19th-century French countryside, securing his place as a respected animalier and landscapist in the annals of art history.