Introduction

Adolphe Joseph Thomas Monticelli stands as a unique and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. Born in Marseille on October 14, 1824, and passing away in the same city on June 29, 1886, Monticelli forged a path distinct from the mainstream movements of his time. Though rooted in Romanticism, his intensely personal style, characterized by vibrant colours, thick impasto, and dreamlike atmospheres, anticipated later developments like Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and even Fauvism. While not achieving widespread fame during his lifetime, his work resonated deeply with certain artists, most notably Vincent van Gogh, securing his place as an influential, albeit often overlooked, precursor of modern painting.

Early Life and Artistic Training

Born into a family of modest means with Italian origins, Monticelli's artistic journey began in his native Marseille. He received his initial art education in the city, demonstrating an early aptitude for painting. Seeking to further hone his skills, he travelled to Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world at the time. There, he enrolled in the studio of Paul Delaroche, a prominent academic painter known for his historical scenes. Delaroche's precise technique likely provided a foundational contrast to the freer style Monticelli would later develop.

Beyond formal instruction, Monticelli immersed himself in the masterpieces housed within the Louvre Museum. He spent considerable time studying the works of past masters, absorbing lessons in composition, colour, and technique. Among those who particularly captured his attention were the great Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, whose dramatic flair and rich colour palettes clearly left a mark, and Antoine Watteau, the master of the Rococo fête galante, whose depictions of elegant figures in park settings would echo in Monticelli's own courtly and pastoral scenes. This period of study was crucial in shaping his artistic sensibilities, blending academic grounding with a deep appreciation for Romantic colour and Rococo grace.

Artistic Style and Development

Monticelli's artistic style is instantly recognizable yet difficult to categorize neatly. It evolved from a Romantic sensibility but pushed beyond its conventions into a realm of heightened subjectivity and expressive technique. His most defining characteristic is his handling of paint and colour. He applied paint thickly, often using a palette knife alongside brushes, creating a heavily textured surface known as impasto. This technique gives his canvases a tactile, almost sculptural quality, where the paint itself seems to vibrate with energy.

His colour palette was equally bold and unconventional for its time. Monticelli employed rich, jewel-like tones, often juxtaposing complementary colours to create a shimmering, incandescent effect. Light in his paintings is not merely descriptive but seems to emanate from within the colours themselves, contributing to the often dreamlike or fantastical atmosphere of his work. This focus on colour and texture over precise representation marks him as a significant forerunner to later modernist movements that prioritized subjective expression and the material qualities of paint.

The influence of artists like Eugène Delacroix is evident in the richness and intensity of Monticelli's colour choices and the overall Romantic emotionalism found in many works. From Antoine Watteau, he drew inspiration for his depictions of fêtes galantes – elegant gatherings in park-like settings, often imbued with a sense of nostalgia or poetic fantasy. However, Monticelli transformed these influences into something entirely his own, less concerned with narrative clarity or realistic detail and more focused on evoking a mood and dazzling the eye with colour and light.

Subject Matter and Themes

Monticelli explored a diverse range of subjects throughout his career. His early work included portraits and historical or mythological scenes, reflecting his academic training. However, he became particularly known for several recurring themes. Inspired by Watteau, he frequently painted fêtes galantes, depicting elegantly dressed figures, often in period costume, conversing, strolling, or listening to music in lush, imaginary landscapes. These scenes are less about specific events and more about capturing an atmosphere of refined leisure, tinged with melancholy or fantasy.

Still life was another important genre for Monticelli, especially in his later years. His still lifes, often featuring flowers, fruit, or ceramics, are far removed from traditional, meticulous renderings. Instead, they are explosions of colour and texture, where the objects seem almost dissolved into the thick, vibrant paint. His flower paintings, in particular, are celebrated for their energy and the way he captured the ephemeral beauty of blooms through bold, expressive strokes.

Orientalist themes also appear in his work, reflecting a common fascination in 19th-century France with the cultures of North Africa and the Middle East. These paintings often feature figures in exotic attire or settings, rendered with the same rich colour and textured surfaces characteristic of his style. Additionally, he painted landscapes, particularly scenes of his native Provence, and portraits, though often these were less about capturing a precise likeness and more about exploring character through colour and brushwork. Across all these themes, a sense of poetry and a slightly unreal, dreamlike quality often pervades his work.

Life in Paris and Return to Marseille

Monticelli spent significant periods of his career in Paris, immersing himself in the city's vibrant artistic life. He associated with other artists and sought patronage, exhibiting his work where he could. Despite his undeniable talent and unique vision, he struggled financially for much of his life. His style was perhaps too unconventional for mainstream tastes and the official Salon system, which favoured more academic or, later, Impressionist approaches. Nevertheless, he remained fiercely dedicated to his art, continuing to paint prolifically even during times of hardship.

Around 1870, possibly prompted by the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent turmoil of the Paris Commune, Monticelli returned to his hometown of Marseille. He would spend the remainder of his life there, living in relative poverty but entering what many consider his most mature and powerful artistic phase. Away from the pressures and trends of the Parisian art scene, his style became even more personal and expressive. He continued to paint his characteristic fêtes galantes, still lifes, and landscapes, often selling works for small sums to make ends meet.

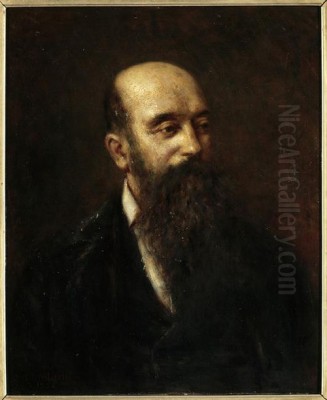

Accounts from this later period describe Monticelli as a somewhat solitary and eccentric figure. He was reportedly taciturn, preferring the company of a few close friends, and known for his simple, sometimes unconventional attire. This image of the dedicated, perhaps misunderstood artist living modestly while producing works of dazzling richness adds to the mystique surrounding his life and career. His final decade, from the mid-1870s until his death in 1886, is often cited as the period when his art reached its peak of spontaneity and expressive power.

Influence on Vincent van Gogh

Perhaps Monticelli's most significant legacy lies in his profound impact on Vincent van Gogh. Although the two artists never met – Monticelli died in June 1886, the same year Van Gogh arrived in Paris – Van Gogh discovered Monticelli's work shortly after his arrival, likely through the art dealer Alexander Reid, who handled works by the Marseille painter. Van Gogh was immediately captivated by Monticelli's vibrant colour and thick application of paint.

At a time when Van Gogh was seeking to move away from the darker palette of his earlier Dutch period, Monticelli's work offered a revelation. He saw in Monticelli a kindred spirit, an artist who used colour not just descriptively but emotionally, and who applied paint with a passion and directness that Van Gogh himself was striving for. The encounter with Monticelli's paintings is considered a key catalyst in the brightening of Van Gogh's own palette and his adoption of a more expressive, impasto technique during his Paris period and subsequent move to the South of France.

Van Gogh's admiration for Monticelli was deep and frequently expressed. In letters to his brother Theo, he praised Monticelli's artistry and lamented his lack of recognition. He even purchased Monticelli flower pieces to study. Famously, Van Gogh wrote, "I sometimes think I am really continuing that man," indicating the powerful sense of connection and artistic lineage he felt. He believed Monticelli was a singular talent whose approach to colour was ahead of its time. This acknowledged debt solidifies Monticelli's importance as a crucial influence on one of the towering figures of Post-Impressionism.

Relationship with Paul Cézanne

While Monticelli's influence on Van Gogh occurred posthumously through his paintings, his relationship with Paul Cézanne was one of direct friendship and artistic exchange. Cézanne, another major figure of Post-Impressionism, was also from the South of France (Aix-en-Provence, near Marseille). During the 1860s and possibly later, Monticelli and Cézanne spent time together, reportedly painting side-by-side on excursions into the Provençal countryside.

The exact nature and extent of Monticelli's influence on Cézanne are debated by art historians, but it is generally acknowledged that the older artist's bold use of colour and textured paint application left an impression on the developing Cézanne. Some see echoes of Monticelli's rich surfaces and vibrant palette in certain phases of Cézanne's work. While Cézanne would ultimately pursue a very different artistic path, focusing on structure, form, and the underlying geometry of nature, his early interactions with Monticelli likely contributed to his own explorations of colour and paint handling.

Their shared Provençal roots and their time painting together represent an interesting intersection of two highly individualistic artists who both operated somewhat outside the main currents of Parisian art. Their friendship highlights the rich artistic environment of Provence and underscores Monticelli's role not just as a solitary figure but as someone who engaged with and potentially influenced other key artists of his generation.

Other Contemporaries and Connections

Beyond Van Gogh and Cézanne, Monticelli interacted with other artists and his work existed within the broader context of 19th-century French art. During his time in Paris, he formed a friendship with Camille Pissarro, one of the key figures of Impressionism. This connection suggests Monticelli was not entirely isolated from the avant-garde circles, and indeed, he occasionally exhibited his work alongside more progressive artists.

While his style differed significantly from the Impressionists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, or Alfred Sisley, who were primarily concerned with capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere with broken brushwork, Monticelli's emphasis on colour and expressive technique can be seen as running parallel to, or even anticipating, some aspects of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. His work, however, remained more rooted in Romantic fantasy and subjective vision than in the objective observation of nature that characterized much Impressionist painting.

His foundational influences remained important throughout his career. The Romanticism of Delacroix continued to inform his dramatic use of colour, while the elegance and thematic content of Watteau's fêtes galantes provided a recurring template. His teacher, Paul Delaroche, represented the academic tradition against which Monticelli, like many artists of his generation, ultimately reacted. Some art historians also draw parallels between Monticelli's rich, textured surfaces and the work of Barbizon School painters like Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, who also favoured lush forest scenes and jewel-like effects. These connections place Monticelli within a complex web of artistic relationships and influences.

Representative Works

Monticelli's oeuvre is extensive, but several works stand out as representative of his unique style and recurring themes. Paintings titled Les Precieuses Ridicules (The Absurdly Pretentious Ladies), likely inspired by Molière's play, exemplify his take on the fête galante, featuring elegantly dressed figures in a park setting, rendered with his characteristic shimmering colour and thick texture. These scenes often possess a theatrical, almost stage-like quality.

His landscapes and seascapes, such as Port of Cassis, capture the light and atmosphere of the Mediterranean coast, but filtered through his subjective vision. The forms of boats, water, and coastline are suggested rather than precisely defined, dissolved into a vibrant tapestry of colour and impasto. These works demonstrate his ability to convey the essence of a place through purely painterly means.

Still lifes like Still Life with Sardines and Sea Urchins or the numerous Vase of Flowers paintings showcase his mastery of colour and texture in a more intimate format. Flowers, fruit, and objects become pretexts for dazzling displays of pigment, applied with energy and freedom. The Vase of Flowers (circa 1875) housed in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is a prime example, clearly showing the kind of work that captivated Van Gogh.

Other notable works mentioned in various records include Girls at the Fountain, Heroic Encounter in the Park, The Peacock Garden (circa 1860), Reading in the Garden, A Garden Party, Festa Campesina, Quatre figures dans un parc (Four Figures in a Park), Christ Blessing the Children, and Arlésiennes ladies, le conciliabule. This range demonstrates his versatility across different genres while maintaining his distinctive stylistic signature.

Reception and Legacy

During his lifetime, Monticelli occupied an ambiguous position in the art world. While appreciated by a circle of collectors and fellow artists, he never achieved the widespread acclaim or financial success of some contemporaries. His highly individual style did not fit easily into established categories and was often misunderstood or dismissed by critics accustomed to more conventional approaches. There are accounts of negative criticism, such as a Scottish curator reportedly finding an exhibition of his work "appalling." The fact that the writer Oscar Wilde, an aesthete with a keen eye, owned a Monticelli but later had to sell it due to financial difficulties, speaks to both the painting's desirability among connoisseurs and the artist's fluctuating market value.

However, Monticelli's reputation began to grow posthumously, particularly as the artists he influenced, like Van Gogh and Cézanne, gained prominence. Art historians started to recognize his role as an important transitional figure and a precursor to modern art movements. His bold colourism and expressive brushwork were seen as anticipating Fauvism and Expressionism. His emphasis on the material quality of paint and subjective experience resonated with later modernist sensibilities.

His work found particular favour among collectors in Great Britain, especially Scotland, partly thanks to dealers like Alexander Reid. While perhaps less known to the general public than the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists he influenced, Monticelli is now acknowledged as a significant innovator. He stands as a testament to the power of individual vision, an artist who pursued his unique path, creating a body of work that, while perhaps challenging for its time, ultimately proved remarkably forward-looking and influential.

Collections and Market

Today, Adolphe Monticelli's works are held in the collections of major museums around the world, affirming his art historical significance. Prominent institutions housing his paintings include the Musée du Louvre and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Cantini Museum (housing modern art) in his native Marseille, the Tate Britain in London, the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, and various museums across the United States.

His paintings also continue to appear on the art market, fetching respectable prices at auction, although generally not reaching the astronomical sums commanded by the artists he influenced. Auction records show consistent interest in his work. For example, Festa Campesina was offered at Christie's in London in 2008. Works like Les Precieuses Ridicules, Reading in the Garden, and Fan Girl have appeared with estimates ranging from a few thousand to tens of thousands of euros or dollars, depending on size, period, and quality.

The presence of his works in both public institutions and private collections, alongside a steady market presence, indicates his established place in the canon of 19th-century European art. While perhaps still a "painter's painter" – more deeply appreciated by artists and connoisseurs than by the wider public – his legacy is secure, valued for its unique beauty and its role in the evolution towards modern art.

Conclusion

Adolphe Monticelli remains a fascinating figure in art history – an artist of intense originality whose work bridged Romanticism and modernism. His dazzling use of colour, thick impasto, and dreamlike subject matter created a unique visual language that stood apart from the dominant trends of his day. Though he faced financial struggles and limited recognition during his lifetime, his dedication to his personal vision never wavered. His posthumous influence, particularly on Vincent van Gogh, was profound, helping to shape the course of Post-Impressionism. Today, Monticelli is recognized as a significant precursor of modern art, an innovator whose vibrant, textured canvases continue to captivate viewers with their poetic beauty and expressive power. His life and work serve as a powerful reminder that artistic influence often flows through less conventional channels, and that true originality endures beyond the vagaries of contemporary fame.